SAT Exam > SAT Questions > Directions: Each passage below is accompanied...

Start Learning for Free

Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.

Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.

After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.

Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.

After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.

Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.

Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution

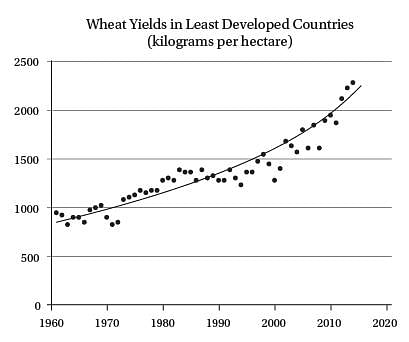

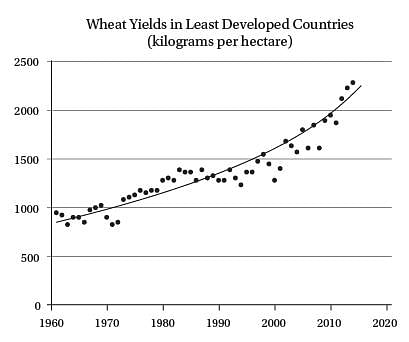

Working in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaug's work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.

(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “You're wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agriculture's forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.

Borlaug's professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaug's seeds, and the yield was 600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaug's work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.

His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.

(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexico's two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.

In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the world's most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.

Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, India's cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.

Norman Borlaug and the Green Revolution

Working in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaug's work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.

(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “You're wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agriculture's forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.

Borlaug's professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaug's seeds, and the yield was 600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaug's work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.

His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.

(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexico's two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.

In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the world's most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.

Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, India's cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.

Q. Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?

- a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.

- b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.

- c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.

- d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.

Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?

Verified Answer

Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions...

Choice A is inappropriate because the paragraph is about Borlaug’s academic career and his early interest in agriculture, not his career in sports. Choice B is inappropriate because this paragraph is about his college years, not his childhood on the farm. Choice C is inappropriate also because the time from of his later Forest Service work is out of place in a paragraph about his college career.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Similar SAT Doubts

Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?.

Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice Directions: Each passage below is accompanied by a number of questions. For some questions, you will consider how the passage might be revised to improve the expression of ideas. For other questions, you will consider how the passage might be edited to correct errors in sentence structure, usage, or punctuation. A passage or a question may be accompanied by one or more graphics (such as a table or graph) that you will consider as you make revising and editing decisions.Some questions will direct you to an underlined portion of a passage. Other questions will direct you to a location in a passage or ask you to think about the passage as a whole.After reading each passage, choose the answer to each question that most effectively improves the quality of writing in the passage or that makes the passage conform to the conventions of Standard Written English. Many questions include a "NO CHANGE" option. Choose that option if you think the best choice is to leave the relevant portion of the passage as it is.Question based on the following passage and supplementary material.Norman Borlaug and the Green RevolutionWorking in relative obscurity, (1) the efforts of one 20th century scientist may have saved nearly 1 billion lives. His name is Norman Borlaug, and he founded the scientific movement that we now call the Green Revolution. Borlaug received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1970 for his work around the world to develop and distribute high-yield varieties of wheat and rice, promote better agricultural management techniques, and (2) he modernized irrigation infrastructure. Largely as a result of Borlaugs work, (3) wheat yields throughout the world increased by over 200% between 1960 and 2014.(4) Born in 1914 on a farm in Cresco, Iowa, Borlaug came of age during the heart of the Depression. His grandfather convinced Norman to pursue an education, saying, “Youre wiser to fill your head now if you want to fill your belly later on.” Although he failed the entrance exam for the University of Minnesota, he did gain admittance to its two-year General College, and did well enough there to transfer to the College of Agricultures forestry program. (5) He became fascinated by work his professors were doing in breeding food crops to be resistant to parasitic (6) fungi. He decided to pursue research in plant pathology and breeding.Borlaugs professional work began in the 1940s, when he developed a high-yield and disease-resistant variety of wheat to help Mexican farmers become more productive. By 1963, most of the wheat crop in Mexico was grown from Borlaugs seeds, and the yield was600% greater than it had been in 1944. (7) Borlaugs work helped Mexico enormously in its effort to become more food secure, and even became a net exporter of wheat by 1963.His work went far beyond just handing out drought-resistant seeds to Mexican farmers.(8) Borlaug showed them how to better manage their productivity by taking advantage of Mexicos two growing seasons. He also showed them how to use genetic variations among crops in a single field to maximize disease resistance. Although some of the genetic strains might (9) succumb to the pathogens (disease-causing agents), those strains could easily be replaced with new, resistant lines, thereby maintaining higher crop yields.In the early 1960s, Borlaug traveled to two of the worlds most impoverished nations, India and Pakistan, to share his insights with government officials and farmers who were struggling with food shortages. The situation was so (10) dire as that the biologist Paul Ehrlich speculated in his 1968 bestseller The Population Bomb that “in the 1970s and 1980s, hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now.” Ehrlich singled out India for particular devastation because of its traditional and bureaucratic resistance to change.Fortunately, Borlaug kept working anyway. Between 1965 and 1970, Indias cereal crop yield increased by 63%, and by 1974, India was self-sufficient in the production of all cereals. For the last 50 years, food production in India and Pakistan has increased faster than the (11) population. This is due largely to the work of Norman Borlaug.Q.Which choice provides the most relevant and cohesive information?a)Borlaug was a standout wrestler for the university, even reaching the Big Ten semifinals.b)Borlaug’s interest in agriculture had been cultivated years previously on his grandfather’s farm.c)Coincidentally, Borlaug would later work for the United States Forest Service in Massachusetts.d)The move was an excellent fit for Norman’s skills and interests.Correct answer is option 'D'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice SAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.