Case Based Questions: Nature of Contracts | Business Laws for CA Foundation PDF Download

CA Foundation - Indian Contract Act, 1872 Case-Based Questions (Subjective)

Case Study 1: The Wedding Planner’s Promise

Rahul, a wedding planner, agrees to organize Priya’s wedding for ₹5 lakhs, promising a grand event with specific decorations. Priya agrees to pay the amount upon completion. However, Rahul later discovers he cannot deliver the promised floral arrangements due to a supplier issue and informs Priya he will not proceed unless she pays an extra ₹1 lakh.

Question: Discuss whether Rahul and Priya have formed a valid contract under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and explain the essential elements required for their agreement to be enforceable by law.

Answer: Under Section 2(h) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, a contract is an agreement enforceable by law, comprising an agreement (Section 2(e)) and legal enforceability. An agreement requires a valid offer, acceptance, and consideration. For Rahul and Priya, Rahul’s offer to organize the wedding for ₹5 lakhs was accepted by Priya, with her promise to pay as consideration, forming an agreement. However, for this to be a valid contract, it must meet the essentials under Section 10: free consent, competent parties, lawful consideration, lawful object, and not being expressly void. Additionally, there must be an intention to create a legal relationship, certainty of terms, and possibility of performance. In this case, both parties are competent (adults of sound mind), and the object (wedding planning) is lawful. However, Rahul’s demand for an extra ₹1 lakh may constitute coercion under Section 15, making the contract voidable at Priya’s option, as seen in Chinnaya v. Ramayya (1882), which upheld that consideration must be lawful and freely given. If the supplier issue makes performance impossible, the contract may become void under Section 56. Thus, while an agreement exists, its enforceability depends on resolving these issues, ensuring all essentials are met.

Case Study 2: The Social Media Influencer’s Deal

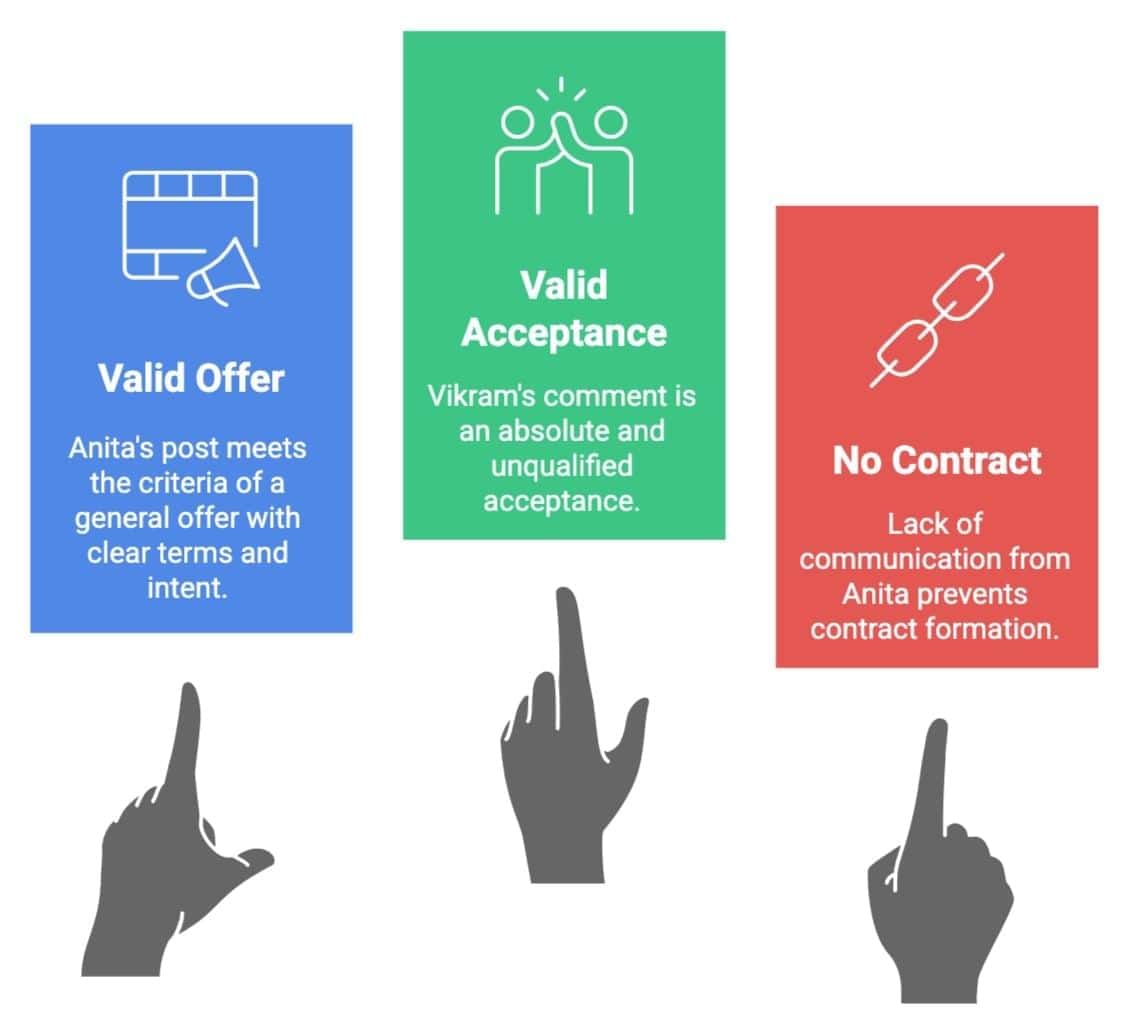

Anita, a social media influencer, posts online offering to promote any brand’s product for ₹50,000 per post. Vikram, a startup owner, comments, “I accept, let’s promote my new energy drink!” Anita doesn’t respond but later claims Vikram owes her ₹50,000 for her post about his drink.

Question: Explain whether Anita’s online post constitutes a valid offer under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and whether Vikram’s comment creates a binding contract.

Answer: Under Section 2(a) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, an offer is a person’s willingness to do or abstain from doing something to obtain another’s assent. Anita’s post offering to promote products for ₹50,000 is a general offer to the public, as established in Lalman Shukla v. Gauri Dutt (1913), where a public offer required knowledge for acceptance. It must intend to create legal relations, be certain, and be communicated (Page 18). Anita’s post meets these criteria, as it specifies the price and service, implying a legal intent. Vikram’s comment, “I accept,” indicates assent, but for a valid acceptance under Section 2(b), it must be absolute, unqualified, and communicated in the prescribed mode (Page 23). Since Anita didn’t specify a mode, Vikram’s comment is a valid acceptance by conduct, forming a promise. However, Anita’s lack of response raises questions about communication completion (Section 4). If Vikram’s acceptance was received and Anita performed, a binding contract exists. Otherwise, without clear communication, no contract is formed.

Case Study 3: The Lost Puppy Reward

Suresh, desperate to find his lost puppy, puts up posters offering a ₹10,000 reward to anyone who returns it. Meena, unaware of the posters, finds the puppy and returns it to Suresh, later learning about the reward and claiming it.

Question: Analyze whether Meena is entitled to the reward under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, focusing on the rules of offer and acceptance.

Answer: Under Section 2(a) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, Suresh’s poster is a general offer to the public, promising ₹10,000 for returning his puppy (Page 17). For a valid acceptance under Section 2(b), the offeree must have knowledge of the offer and act with intent to accept, as clarified in Lalman Shukla v. Gauri Dutt (1913), where a servant’s act without knowledge of a reward offer was not acceptance. Meena, unaware of the offer when returning the puppy, did not act with the intent to accept, as her action was not in response to the offer. Section 4 requires that the offer’s communication is complete when it comes to the offeree’s knowledge. Since Meena learned of the reward only after returning the puppy, her act does not constitute acceptance under Section 8, which allows acceptance by performing conditions of a general offer. Thus, no contract was formed, and Meena is not entitled to the reward, as her action lacked the necessary knowledge and intent to accept the offer.

Case Study 4: The Auction Mishap

Karan attends an auction for vintage cars, bidding ₹3 lakhs for a 1960s model. Before the auctioneer’s hammer falls, Karan shouts, “I withdraw my bid!” The auctioneer ignores him and declares the car sold to Karan.

Question: Discuss whether a valid contract was formed between Karan and the auctioneer under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, considering the rules of offer revocation.

Answer: Under Section 2(a) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, Karan’s bid is an offer to purchase the car, and the auctioneer’s acceptance occurs when the hammer falls, forming a promise (Page 14). Section 5 allows an offeror to revoke their offer before the communication of acceptance is complete as against them. In an auction, acceptance is complete when the auctioneer declares the sale by the fall of the hammer, as noted in Payne v. Cave (1789), a principle applied in Indian law in Consolidated Coffee Ltd. v. Coffee Board (1980), where the Supreme Court held that a bid can be withdrawn before the hammer falls. Karan’s shout, “I withdraw my bid,” before the hammer fell, constitutes a timely revocation under Section 4, communicated to the auctioneer. As per Section 4, revocation is complete against the offeror when put into transmission and against the offeree when it reaches them. Karan’s shout effectively revoked the offer before the auctioneer’s acceptance. Thus, no valid contract was formed, as the offer was revoked before acceptance, and the auctioneer cannot enforce the sale against Karan.

Case Study 5: The Family Promise

Ravi promises his niece, Sonia, ₹10,000 if she scores above 90% in her CA Foundation exams. Sonia works hard and achieves 92%, but Ravi refuses to pay, claiming it was a casual promise.

Question: Explain whether Sonia can enforce Ravi’s promise as a contract under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, focusing on the intention to create a legal relationship.

Answer: Under Section 2(h) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, a contract requires an agreement enforceable by law, which includes an intention to create a legal relationship (Page 6). Ravi’s promise to pay Sonia ₹10,000 for scoring above 90% is an offer, and Sonia’s performance (scoring 92%) could be seen as acceptance by conduct under Section 8. However, for enforceability, both parties must intend a legal obligation, as seen in Balfour v. Balfour (1919), a principle followed in Rajlukhy Dabee v. Bhootnath Mookerjee (1900), where a domestic agreement was held non-binding due to lack of legal intent. Ravi’s claim that it was a casual promise suggests no intention to create a legal obligation. Since this is a family arrangement, courts typically presume no legal intent unless explicitly stated. Sonia’s effort does not change this, as the agreement lacks the essential element of legal enforceability. Thus, Sonia cannot enforce the promise as a contract, as it is a social agreement, not a legally binding contract.

Case Study 6: The Coffee Shop Incident

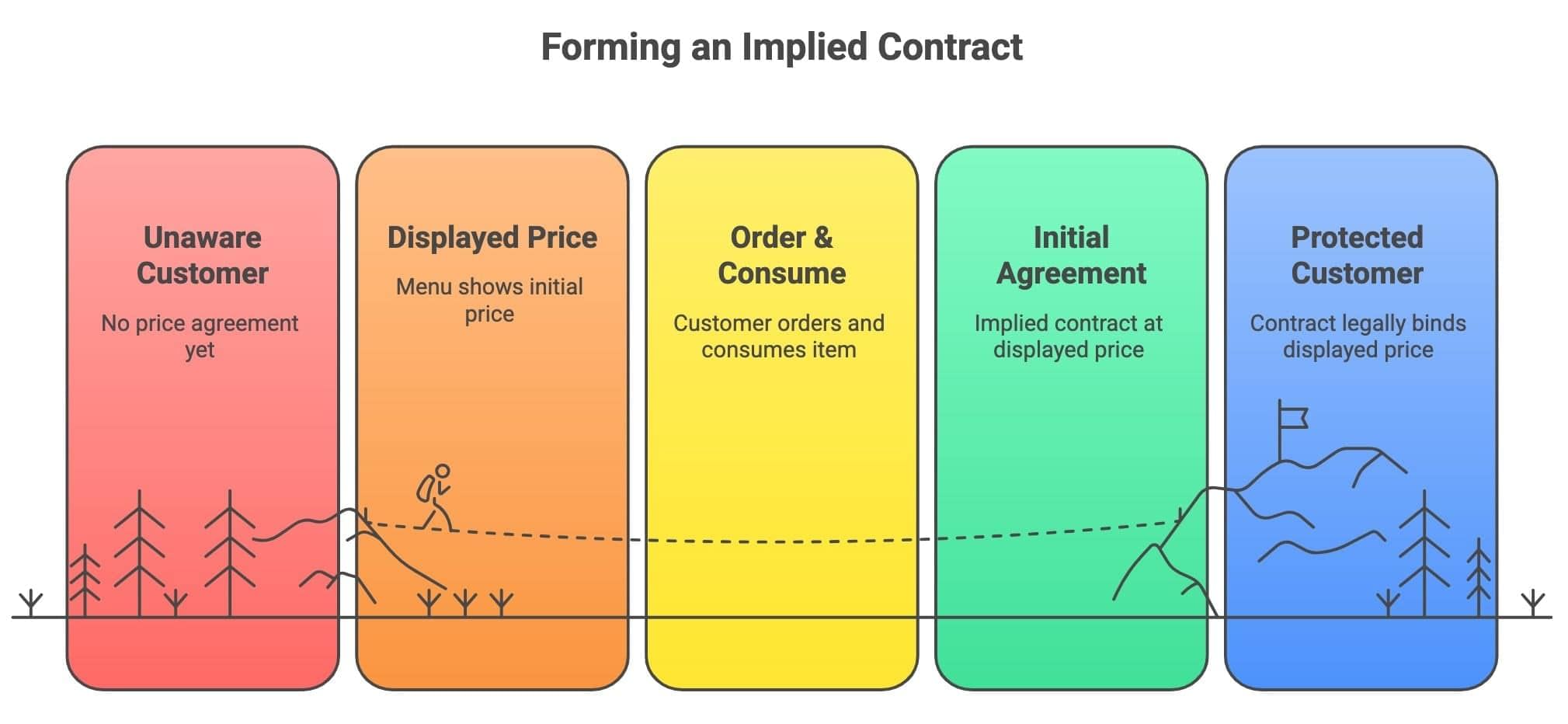

Neha enters a trendy coffee shop, orders a cappuccino, and drinks it. When she goes to pay, the cashier demands ₹500, citing a new price list. Neha argues she assumed the price was ₹200 based on the menu board.

Question: Determine whether an implied contract exists between Neha and the coffee shop under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and explain the type of contract formed.

Answer: Under Section 9 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, an implied contract arises when a proposal or acceptance is made otherwise than in words, through conduct or actions (Page 13). Neha’s order and consumption of the cappuccino imply acceptance of the coffee shop’s offer to sell at the displayed price, forming an implied contract, as seen in Uttar Pradesh State Road Transport Corporation v. State of U.P. (2005), where conduct implied a contractual obligation. The menu board’s price of ₹200 constitutes a specific offer, and Neha’s order is acceptance by conduct, creating a promise to pay ₹200. The cashier’s demand for ₹500 post-consumption does not alter the original offer unless Neha was informed of the new price before ordering. Since the contract is executed (both parties performed their obligations—coffee delivered, consumed), it is valid and binding for ₹200. The coffee shop cannot enforce the higher price, as the implied contract was based on the displayed price, making it an executed, implied contract.

Case Study 7: The Smuggled Goods Deal

Vijay agrees with Arjun to buy 100 kg of prohibited spices for ₹2 lakhs, promising to share profits from resale. When Vijay refuses to pay Arjun’s share, Arjun threatens to sue.

Question: Discuss whether Arjun can enforce the agreement under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and explain the legality of the contract’s object.

Answer: Under Section 23 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, an agreement’s consideration or object is unlawful if it is prohibited by law, fraudulent, or opposed to public policy (Page 9). Vijay and Arjun’s agreement to buy and sell prohibited spices is illegal, as it involves dealing in goods forbidden by law (Example 15, Page 9). Section 2(g) states that an agreement not enforceable by law is void, and illegal agreements are void ab initio (Page 12). In Gherulal Parakh v. Mahadeodas Maiya (1959), the Supreme Court held that agreements with unlawful objects, such as those involving illegal activities, are void ab initio and unenforceable. Additionally, collateral agreements to illegal contracts are also void. Arjun cannot enforce the agreement, as its object (dealing in prohibited spices) is unlawful, making the contract illegal and void. Courts will not entertain claims arising from such agreements, and parties are liable for punishment under relevant laws (Page 12). Thus, Arjun has no legal remedy to claim his share, and the agreement is unenforceable under the Indian Contract Act, 1872.

Case Study 8: The Faulty Laptop Sale

Sanjay offers to sell his laptop to Meera for ₹40,000, assuring her it’s in perfect condition. Meera agrees, but after payment, she discovers the laptop is faulty. Sanjay claims he was coerced into the sale by Meera’s persistent demands.

Question: Explain whether Meera can rescind the contract under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and discuss the concept of a voidable contract.

Answer: Under Section 2(i) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, a voidable contract is enforceable at the option of one party but not others, often due to lack of free consent (Page 10). Sanjay’s offer and Meera’s acceptance formed an agreement, but if Sanjay’s consent was obtained through coercion (Section 15), the contract is voidable at his option (Example 20, Page 10). However, Meera’s claim hinges on misrepresentation, as Sanjay assured the laptop’s condition, which was false, potentially making the contract voidable at her option under Section 19. In Shri Krishnan v. Kurukshetra University (1976), misrepresentation was held to justify rescission if it induced the contract. Meera can rescind the contract if she proves Sanjay’s misrepresentation was material and induced her agreement. She may seek to cancel the contract and recover her payment or claim damages. If Sanjay’s coercion claim is unsubstantiated, the contract remains valid unless Meera exercises her right to rescind. Thus, the contract is voidable at Meera’s option due to misrepresentation, allowing her to rescind within a reasonable time.

Case Study 9: The Online Bookstore Deal

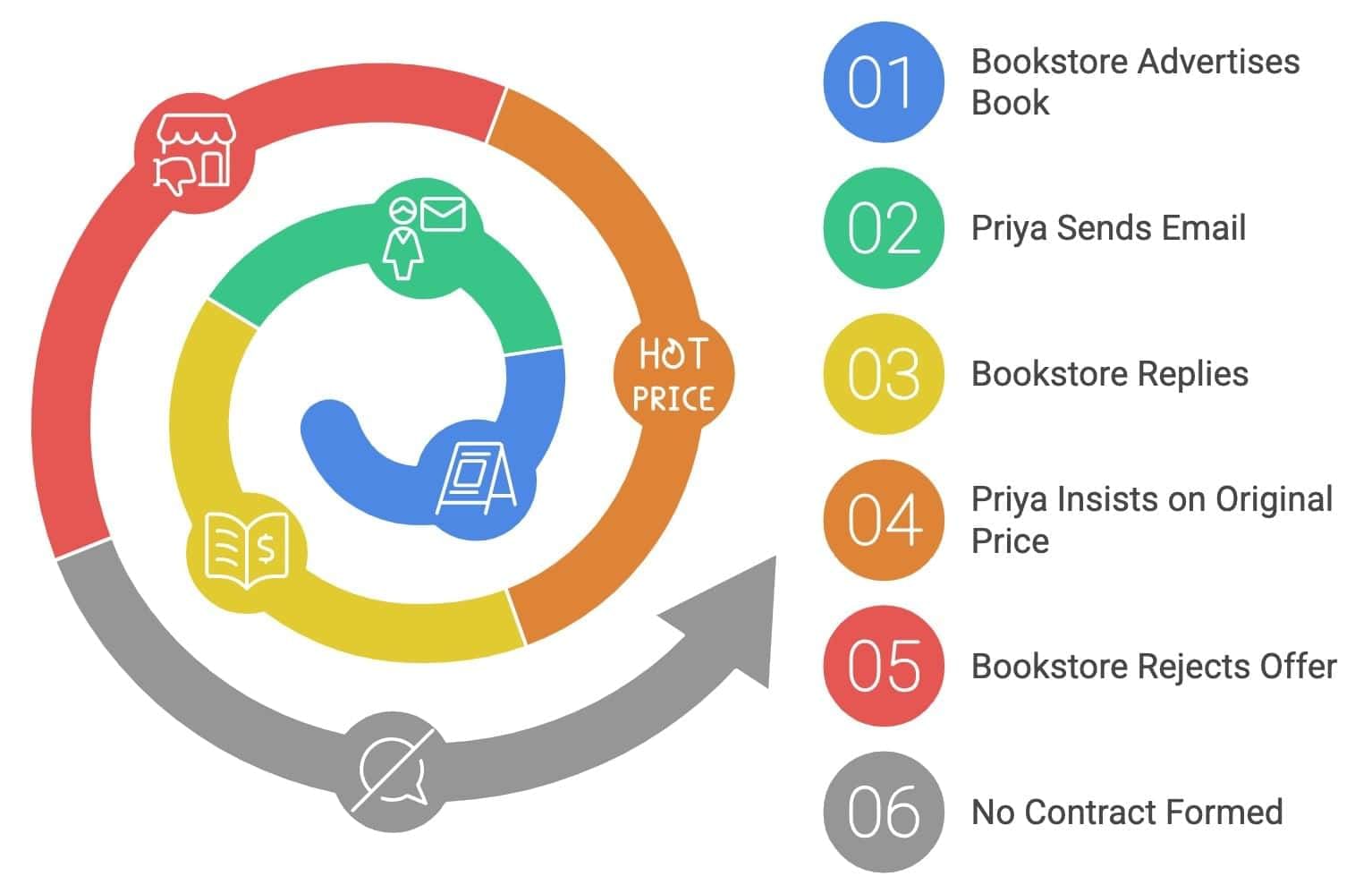

An online bookstore advertises a rare book for ₹5,000. Priya emails her acceptance to buy it, but the bookstore replies that the price was a typo and should be ₹50,000. Priya insists on the original price.

Question: Determine whether the bookstore’s advertisement is an offer or an invitation to offer under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, and whether Priya’s email forms a contract.

Answer: Under Section 2(a) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, an offer is a final expression of willingness to be bound, while an invitation to offer invites others to make offers. The bookstore’s advertisement of a book for ₹5,000 is an invitation to offer, as it seeks offers from potential buyers, as clarified in Harvey v. Facey (1893), a principle followed in Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain v. Boots Cash Chemists (1953) and applied in Indian law. Priya’s email is an offer to buy at ₹5,000, which the bookstore did not accept, instead clarifying the price as ₹50,000, effectively rejecting Priya’s offer. For a contract to form, the bookstore must accept Priya’s offer unconditionally (Section 7). Since the bookstore rejected the offer due to the pricing error, no contract was formed. Priya cannot enforce the ₹5,000 price, as the advertisement was not a binding offer but an invitation to negotiate, and her email did not result in a valid acceptance by the bookstore.

Case Study 10: The Courier’s Mistake

Raj sends a letter offering to sell his bicycle to Simran for ₹10,000, stating she must reply by post within a week. Simran posts her acceptance the next day, but the letter is lost in transit. Raj sells the bicycle to another buyer, assuming Simran didn’t accept.

Question: Discuss the validity of Simran’s acceptance and whether a contract exists under the Indian Contract Act, 1872, focusing on communication rules.

Answer: Under Section 4 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, communication of acceptance is complete against the offeror when it is put into a course of transmission, out of the acceptor’s power, and against the acceptor when it reaches the offeror. Simran’s acceptance, posted as prescribed, was complete against Raj when mailed, even if lost, as per the postal rule in Adams v. Lindsell (1818), followed in Bhagwandas Goverdhandas Kedia v. Girdharilal Parshottamdas & Co. (1966), where the Supreme Court upheld that acceptance by post binds the offeror upon dispatch. Raj’s sale to another buyer does not negate this, as he could not revoke his offer after Simran’s acceptance was dispatched (Section 5). Since Raj specified acceptance by post, Simran’s compliance forms a valid contract, as her acceptance was absolute and unqualified (Section 7). The loss of the letter does not affect the contract’s validity from Raj’s perspective. Thus, a binding contract exists, and Simran can enforce it, potentially claiming the bicycle or damages for Raj’s breach.

|

32 videos|185 docs|57 tests

|

FAQs on Case Based Questions: Nature of Contracts - Business Laws for CA Foundation

| 1. What are the essential elements required for a contract to be legally binding? |  |

| 2. How does the concept of consideration work in contract law? |  |

| 3. What are the implications of a breach of contract? |  |

| 4. In what situations can a contract be declared void or voidable? |  |

| 5. What role does mutual consent play in contract formation? |  |