Class 7 Social Science Chapter 6 Let's Explore - The Age of Reorganisation

Page 118: The Age of Reorganisation

Q: Create a timeline on a sheet of paper marking the period from the first year of the 2nd century BCE and ending in the last year of the 3rd century CE. How many years does this period cover? As we progress through the chapter, mark the key individuals, kingdoms and events on the timeline.

Ans: Timeline Creation: Period: From 200 BCE (first year of 2nd century BCE) to 300 CE (last year of 3rd century CE).

Calculation:

- 200 BCE to 1 BCE = 200 years.

- 1 CE to 300 CE = 300 years.

- Total = 200 + 300 = 500 years.

Key Individuals, Kingdoms, and Events:

- 185 BCE: Assassination of last Maurya emperor, rise of Puṣhyamitra Śhunga, founding of Śhunga dynasty.

- 2nd century BCE: Śhunga dynasty rules; Sātavāhana dynasty emerges in Deccan.

- 2nd century BCE: Indo-Greek invasions in northwest.

- 2nd century BCE–3rd century CE: Sangam Age in south India, with Chera, Chola, Pāṇḍya kingdoms.

- 1st century BCE–2nd century CE: Khāravela rules Kalinga under Chedi dynasty.

- 2nd century BCE–5th century CE: Śhaka (Indo-Scythian) rule in northwest.

- 2nd century CE: Kuṣhāna dynasty under Kaniṣhka, peak of empire.

- 3rd century CE: Sātavāhana Empire fragments.

Timeline Example:

- Draw a horizontal line labeled 200 BCE to 300 CE, with increments of 50 years.

- Mark events (e.g., “185 BCE: Śhunga dynasty begins”) with brief notes or symbols (e.g., crown for kings, coin for trade).

Page 124: Some Śhunga Contribution to Art

Q: Below is a panel from the Bharhut Stūpa. Look at the two figures on the right. What are they doing? Can you guess their profession? Notice their attire. What does this tell us about them? List other details that you notice in the panel and discuss your findings in class.

Ans: Analysis of Bharhut Stūpa Panel: Fig. 6.7. A panel from the Bharhut Stūpa

Fig. 6.7. A panel from the Bharhut Stūpa

Actions of Two Figures on Right: Likely worshipping or offering reverence, possibly at a Buddhist shrine, as the panel is from Bharhut Stūpa, known for depicting Buddha’s life. Their posture (e.g., folded hands or kneeling) suggests devotion, common in Buddhist art.

Profession Guess: Likely devotees or lay followers, possibly merchants or artisans, given their detailed attire and the Śhunga period’s trade prosperity. Alternatively, they could be monks or nuns, as Buddhist communities were prominent.

Attire Observations: Figures wear draped garments (e.g., dhotis or saris), typical of Śhunga art (Fig. 6.6, Page 123), indicating modest yet refined clothing suitable for urban or religious settings. Possible jewelry (e.g., necklaces, as in Fig. 6.6.10) suggests moderate wealth, aligning with Śhunga economic stability.

Other Details in Panel: Presence of a dharmachakra (wheel of dharma, similar to Fig. 6.5.4) or stūpa structure, symbolizing Buddhist teachings. Additional figures (e.g., monks, animals like elephants) may depict a Jātaka story or Buddhist narrative. Intricate carvings (e.g., floral motifs) reflect Śhunga artistic skill.

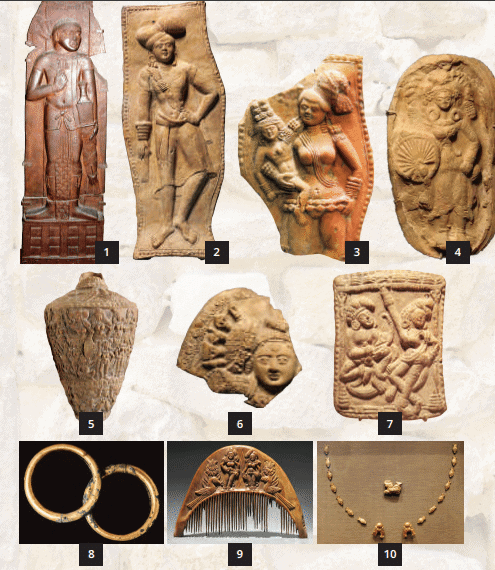

Q: Look closely at the pictures in the collage in Fig 6.6 (on the previous page). In a note, write down your observations on the clothes, the jewellery, and other objects of daily use.

Ans: Observations on Fig. 6.6 Collage: Fig. 6.6.1. Pillar with a Greek warrior. Fig. 6.6.2. Male figure. Fig. 6.6.3. Woman with a The Age of Reorganisation child. Fig. 6.6.4. Woman with a fan. Fig. 6.6.5. A vase. Fig. 6.6.6. Female figure with hair ornaments, terracotta. Fig. 6.6.7. Royal family. Fig. 6.6.8. Bronze bangles covered with a thin layer of gold. Fig. 6.6.9. Comb of ivory. Fig. 6.6.10. Beads of a necklace.

Fig. 6.6.1. Pillar with a Greek warrior. Fig. 6.6.2. Male figure. Fig. 6.6.3. Woman with a The Age of Reorganisation child. Fig. 6.6.4. Woman with a fan. Fig. 6.6.5. A vase. Fig. 6.6.6. Female figure with hair ornaments, terracotta. Fig. 6.6.7. Royal family. Fig. 6.6.8. Bronze bangles covered with a thin layer of gold. Fig. 6.6.9. Comb of ivory. Fig. 6.6.10. Beads of a necklace.

Clothes:

- Greek Warrior (Fig. 6.6.1): Wears a short tunic and armor, typical of Hellenistic style, indicating foreign influence in Śhunga art.

- Male/Female Figures (Figs. 6.6.2, 6.6.3, 6.6.4, 6.6.6): Draped garments (dhotis or saris) with folds, covering torso and legs, suggesting modesty and urban fashion. Women’s attire (Fig. 6.6.4) includes a fan, indicating leisure or status.

- Royal Family (Fig. 6.6.7): Elaborate robes with intricate patterns, denoting high status and wealth.

Jewellery:

- Female Figure (Fig. 6.6.6): Terracotta figure with hair ornaments, likely gold or beaded, indicating adornment trends.

- Bronze Bangles (Fig. 6.6.8): Covered with gold layer, suggesting affordability among elites or artisans.

- Necklace Beads (Fig. 6.6.10): Multiple beads, possibly glass or semi-precious stones, reflecting trade wealth and craftsmanship.

Objects of Daily Use:

- Vase (Fig. 6.6.5): Ceramic, likely for storing water or grains, showing household utility and artistic design.

- Ivory Comb (Fig. 6.6.9): Finely crafted, used for grooming, indicating personal care among higher classes.

Note Summary:

- Clothes: Modest yet detailed drapery, with royal figures in elaborate robes, reflecting social hierarchy.

- Jewellery: Gold-layered bangles, beaded necklaces, and hair ornaments show wealth and trade influence.

- Objects: Vases and ivory combs indicate advanced craftsmanship and daily life sophistication.

Page 126 & 127: Think About It

Q: What, according to you, could the tradition of using the mother’s name at the beginning of a king’s name signify?

Ans: Significance of Mother’s Name in Sātavāhana Tradition:

- Matrilineal Respect: Naming kings like Gautamiputra Sātakarṇi after their mother (Gautamī Balaśhrī) suggests reverence for maternal lineage, possibly reflecting a matrilineal influence in Deccan society, where women held significant roles.

- Political Legitimacy: Associating with a powerful queen mother (e.g., Gautamī’s land donations) strengthened the king’s claim to the throne, leveraging her influence and reputation.

- Cultural Identity: This tradition distinguished Sātavāhana rulers from northern dynasties (e.g., Śhungas), emphasizing regional customs and social structures, fostering a unique identity.

- Gender Roles: It highlights women’s prominence, as seen in the Naneghat queen performing aśhvamedha, indicating their active participation in governance and religion.

- Implications: This practice reflects a society valuing women’s contributions, contrasting with patriarchal norms elsewhere, and underscores the Sātavāhanas’ inclusive ethos, supporting diverse schools of thought.

Q: In the above series of numerals, which ones look somewhat like our modern numerals? Which ones don’t?

Ans: Analysis of Brahmi Numerals:

Numerals Similar to Modern Ones:

1: A vertical line, resembling the modern “1” in its simplicity.

2: Two horizontal lines, somewhat like the modern “2”’s stacked structure.

4: A cross-like shape, partially akin to the modern “4”’s intersecting lines.

9: A curved shape, vaguely similar to the modern “9”’s loop.

Numerals Different from Modern Ones:

6: A complex, angular symbol, unlike the modern “6”’s smooth curve.

7: A hooked shape, distinct from the modern “7”’s sharp angle.

10: A combination of lines, not resembling the modern “10”’s dual digits.

Context: These Brahmi numerals, used in Sātavāhana inscriptions, show the evolution of Indian numeral systems, later influencing modern Arabic numerals via trade. The similarities highlight India’s contribution to global mathematics, while differences reflect script-specific designs.

Q: This sculpture of a yakṣha from Pitalkhora carries an inscription on its hand, kanhadāsena hiramakarena kāta meaning ‘made by Kanahadasa, a goldsmith’. Is it not interesting to see that a goldsmith could also craft a sculpture made of stone? What do you think this tells us about people’s professions at the time?

Ans: Implications of Goldsmith’s Stone Sculpture:

- Multiskilled Artisans: Kanahadasa, a goldsmith, crafting a stone yakṣha indicates artisans were versatile, mastering multiple materials (metal and stone), likely due to demand for diverse art forms in Sātavāhana society.

- Economic Prosperity: The ability to work across mediums suggests a thriving economy, where artisans had resources and patronage to develop varied skills, as seen in Karla caves.

- Cultural Integration: Stone sculptures for Buddhist caves by a goldsmith reflect collaboration across professions, supporting religious diversity (Vāsudeva, Buddhist, Jain patronage).

- Social Mobility: Artisans like Kanahadasa signing their work (inscription) indicates recognition, suggesting a society where skilled craftsmen held status, unlike rigid caste norms later.

- Broader Insight: Professions in the Sātavāhana period were flexible, driven by trade wealth and cultural patronage, allowing artisans to contribute to monumental art, enhancing the era’s cultural richness.

Page 129: Think About It

Q: Notice the regularity of the rock-cut chambers sculpted nearly two millennia ago. How did artisans achieve such precision with just a chisel and hammer? Picture yourself as a sculptor in that era, shaping stone into art with your own hands. What tools would you use?

Ans: Achieving Precision in Rock-Cut Chambers:

Techniques:

- Planning and Measurement: Artisans likely used charcoal or string to mark precise outlines on rock, ensuring symmetry, as seen in Udayagiri-Khandagiri caves (Page 128).

- Skilled Chiseling: Repeated, controlled strikes with chisels of varying sizes shaped stone, with finer chisels for details (e.g., intricate panels, Page 128).

- Teamwork: Groups of craftsmen worked collaboratively, with apprentices handling rough cuts and masters refining details, maximizing efficiency.

- Polishing: Sandstone or abrasives smoothed surfaces, achieving the regularity noted in the caves’ spacious rooms and statues.

Tools as a Sculptor:

- Chisels: Iron chisels (small for details, large for rough cuts), leveraging Sātavāhana iron technology (chpt 4, Page 94).

- Hammers: Wooden or stone mallets to strike chisels, controlling force for precision.

- Measuring Tools: Ropes or wooden rulers for marking dimensions.

- Abrasives: Sand or stone for polishing surfaces.

- Lamps: Oil lamps to illuminate cave interiors during work.

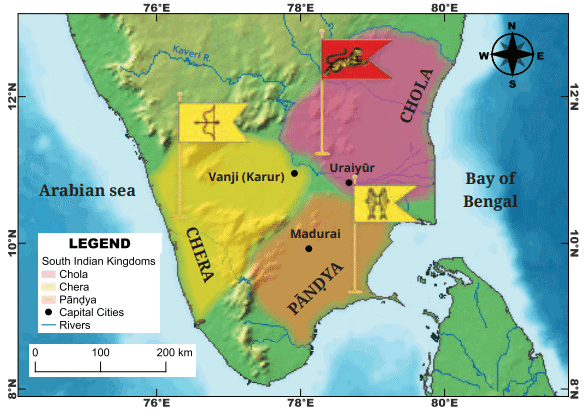

Q: In the map given on next page, you may notice different symbols alongside the names of the kingdoms. What do these symbols represent? Think about how they highlight the unique identities of the kingdoms.

Ans: Symbols on Map (Fig. 6.14, Page 130):

- Cholas (Tiger): Represents strength and ferocity, aligning with their military prowess under Karikāla (Page 130) and naval dominance, emphasizing their aggressive expansion.

- Cheras (Bow and Arrow): Symbolizes archery and warfare, reflecting their martial culture and trade-driven wealth (spices, pearls, Page 133), suggesting readiness to defend economic interests.

- Pāṇḍyas (Fish): Denotes their maritime identity, tied to pearl trade and naval power (Page 133), highlighting their coastal prosperity and connection to Madurai’s trade networks.

- Sātavāhanas (Ujjain Symbol or Ship): Likely a ship (Page 125), signifying maritime trade with Rome, or a regional emblem, underscoring their economic strength via Krishna-Godavari rivers.

- Chedis (Elephant): Suggests power and royalty, fitting Khāravela’s military campaigns (Page 129) and Jain patronage, symbolizing wisdom and strength.

Kingdoms in the South (note that borders are approximate and fluctuated in time).

Kingdoms in the South (note that borders are approximate and fluctuated in time).

Highlighting Identities:

- Symbols reflect each kingdom’s economic, cultural, or military distinctiveness, fostering pride and recognition (e.g., Pāṇḍya pearls).

- They differentiate kingdoms in a competitive south, reinforcing unique governance styles (e.g., Chola irrigation projects) and cultural contributions (Sangam literature).

Page 132 to 134: Think About It

Q: Observe the statue of the king. How is he depicted? What do his posture, clothing, and expression say about his power and status?

Ans: Analysis of Karikāla’s Statue (Fig. 6.16, Page 132): Fig. 6.16. Statue of King Karikāla at the Grand Anicut Memorial Park in Tamil Nadu

Fig. 6.16. Statue of King Karikāla at the Grand Anicut Memorial Park in Tamil Nadu

Posture: Likely standing upright or seated regally, exuding authority, as typical for royal statues. A commanding stance (e.g., holding a scepter or weapon) suggests leadership and military prowess, fitting Karikāla’s defeat of Cheras and Pāṇḍyas (Page 130).

Clothing: Ornate robes or armor, possibly with intricate patterns (similar to Śhunga royal family, Fig. 6.6.7, Page 123), indicate wealth and high status. A crown or turban may signify kingship, aligning with Chola supremacy.

Expression: A calm, resolute face conveys confidence and wisdom, reflecting Karikāla’s role as a just ruler who built the Kallanai dam (Page 132), earning him reverence as a benefactor.

Power and Status: The statue’s grandeur (likely large, at Grand Anicut Memorial Park) and detailed craftsmanship project Karikāla as a powerful, benevolent king, whose irrigation projects made the Kāveri delta the “rice bowl of the South” (Page 132). Symbols like a tiger emblem (Chola identity, Page 130) or staff reinforce his martial and administrative dominance.

Q: Have you ever wondered how historians uncover the trade relations between two distant kingdoms many centuries ago? Let’s take a moment to brainstorm and discuss how this information comes to light.

Ans: Methods to Uncover Trade Relations:

Archaeological Evidence:

- Coins: Chera coins (Fig. 6.18, Page 133) and Sātavāhana ship coins (Page 125) found in Roman territories indicate trade. Roman glass and ointments in India (Page 125) confirm reciprocal exchange.

Coins under Chera Kings

Coins under Chera Kings - Artefacts: Roman pottery or Indian ivory in West Asia (Page 133) shows trade goods’ movement.

- Inscriptions: Naneghat inscriptions (Page 125) mention tolls and donations, reflecting trade revenue. Khāravela’s Hāthigumphā inscription (Page 129) notes pearls from Pāṇḍyas, suggesting trade networks.

- Literary Sources: Megasthenes’ Indika (Page 133) describes Pāṇḍya prosperity and trade with Greeks. Sangam literature (Page 130) details goods like spices in Puhār, linking to Roman markets.

- Trade Routes: Maps (Fig. 6.25, Page 139) show Silk Route and maritime routes via Muziris (Chera port), with ship depictions (Page 125) indicating advanced navigation.

- Foreign Accounts: Greek and Roman texts (e.g., Periplus of the Erythraean Sea) list Indian exports (spices, pearls), corroborating Chera-Roman trade.

Q: The Pāṇḍyas were known for their pearls. Why do you think pearls were an important article of trade during these times?

Ans: Importance of Pearls in Pāṇḍya Trade:

- Luxury and Status: Pearls, rare and lustrous, were prized as jewelry by elites in India, Greece, and Rome (Page 133), symbolizing wealth and power, as seen in Śhunga necklaces (Fig. 6.6.10, Page 123).

- Economic Value: High demand in foreign markets (e.g., Roman Empire) made pearls a lucrative export, boosting Pāṇḍya revenue via coastal trade from Madurai (Page 133).

- Cultural Significance: Pearls adorned deities and royals in Sangam literature (Page 130), enhancing their religious and social value, increasing trade appeal.

- Geographical Advantage: Pāṇḍya’s coastal location (Gulf of Mannar) provided abundant pearl fisheries, giving them a trade monopoly, as noted by Khāravela’s pearl imports (Page 133).

- Maritime Trade: Pāṇḍya naval power (Page 133) facilitated pearl transport to distant ports, integrating them into global networks like the Silk Route (Page 139).

- Impact: Pearls drove Pāṇḍya prosperity, funding art and architecture (Page 133), and their trade prominence strengthened south India’s economic and cultural ties with the world.

Page 135: Invasions of the Indo-Greeks

Q: What do you think might have been the meaning of having deities like Vāsudeva-Kṛiṣhṇa or Lakṣhmī on some Indo-Greek coins?

Ans: Meaning of Deities on Indo-Greek Coins:

- Cultural Assimilation: Depicting Vāsudeva-Kṛiṣhṇa and Lakṣhmī (Page 135) shows Indo-Greeks adopting Indian deities, blending Hellenistic and Indian cultures to appeal to local subjects, as seen in the Heliodorus pillar’s Vāsudeva praise (Page 134).

- Political Legitimacy: Using Indian gods signaled respect for local beliefs, legitimizing Indo-Greek rule in northwest India, where these deities were revered (e.g., Vāsudeva in Sātavāhana tradition, Page 127).

- Religious Syncretism: Combining Greek deities with Indian ones (Page 135) reflected a pluralistic ethos, fostering harmony among diverse populations, similar to Khāravela’s multi-sect council (Page 129).

- Economic Appeal: Coins with familiar deities circulated widely, encouraging trade by resonating with Indian merchants, as trade was vital post-Mauryas (Page 143).

- Example: The Heliodorus pillar’s inscription (Page 135) suggests ambassadors like Heliodorus embraced Indian values, mirrored in coin iconography to unify Greek and Indian identities.

Page 137: Think About It

Q: Do you know where Gāndhāra is? Does it remind you of a character from the epic Mahābhārata?

Ans: Location of Gāndhāra: Gāndhāra was a historical region in northwest India, covering modern-day northwest Pakistan and eastern Afghanistan, centered around cities like Taxila and Peshawar. It was a key area for Kuṣhāna art (Page 137) and Indo-Greek rule (Page 134).

Connection to Mahābhārata: Gāndhāra reminds us of Gāndhārī, a prominent character in the Mahābhārata. She was the princess of Gāndhāra, married to Dhṛtarāṣṭra, king of Hastināpura, and mother of the Kauravas. The region’s name in the epic reflects its historical significance as a cultural and political center, later a hub for Greco-Indian art (Page 137).

Page 140: The Mathurā style

Q: Now that you are familiar with the basic characteristics of the Mathurā and Gāndhāra styles of art, study the pictures of artefacts given in Fig. 6.27 on the right page and try to identify which school of art each artefact belongs to. Write your observations with justifications and discuss your answers with your classmates.

Ans: Characteristics(Page 137, 140):

- Gāndhāra Style: Greco-Roman influence, grey-black schist stone, realistic anatomy, flowing robes, detailed Buddha images (Page 137).

- Mathurā Style: Indian aesthetic, red sandstone, fuller figures, smooth modeling, depicts Indian deities (Kubera, Lakṣhmī, Śhiva, Buddha, yakṣhas), less Greco-Roman influence (Page 140).

Fig. 6.27.1. A scene of the death of Buddha. Fig. 6.27.2. Bodhisattva Maitreya. Fig. 6.27.3. Śhiva linga being worshipped by Kuṣhāna devotees.

Fig. 6.27.1. A scene of the death of Buddha. Fig. 6.27.2. Bodhisattva Maitreya. Fig. 6.27.3. Śhiva linga being worshipped by Kuṣhāna devotees.

Analysis of Fig. 6.27 Artefacts (Page 141):

- Fig. 6.27.1 (Death of Buddha):

- School: Gāndhāra.

- Justification: Likely schist stone, with detailed, realistic figures in flowing robes, typical of Gāndhāra’s Greco-Roman style (Page 137). The scene’s narrative complexity aligns with Gāndhāra Buddha depictions.

- Fig. 6.27.2 (Bodhisattva Maitreya):

- School: Gāndhāra.

- Justification: Realistic anatomy and draped robes suggest Gāndhāra’s Hellenistic influence. The bodhisattva’s serene expression and detailed carving match Gāndhāra’s style (Fig. 6.24, Page 137).

- Fig. 6.27.3 (Śhiva Linga with Kuṣhāna Devotees):

- School: Mathurā.

- Justification: Śhiva linga, an Indian motif, and fuller figures of devotees in red sandstone (Page 140) indicate Mathurā’s Indian aesthetic, less Greco-Roman.

Fig. 6.27.4. A Nāga between two Nāgīs, with an inscription referring to the eighth year of Kaṇiṣhka’s reign. Fig. 6.27.5. Kartikeya, the god of war, and Agni, the god of fire. Fig. 6.27.6. Standing Buddha

Fig. 6.27.4. A Nāga between two Nāgīs, with an inscription referring to the eighth year of Kaṇiṣhka’s reign. Fig. 6.27.5. Kartikeya, the god of war, and Agni, the god of fire. Fig. 6.27.6. Standing Buddha

- Fig. 6.27.4 (Naga between Nagis, Kaniṣhka’s Reign):

- School: Mathurā.

- Justification: Naga deities, Indian mythological figures, and smooth modeling in red sandstone align with Mathurā’s style, focusing on local themes (Page 140).

- Fig. 6.27.5 (Kartikeya and Agni):

- School: Mathurā.

- Justification: Indian war and fire gods in fuller, robust forms, likely red sandstone, reflect Mathurā’s distinct Indian iconography, not Gāndhāra’s realism (Page 140).

- Fig. 6.27.6 (Standing Buddha):

- School: Gāndhāra.

- Justification: A standing Buddha with flowing robes and realistic features, likely in schist, matches Gāndhāra’s detailed, Greco-influenced Buddha images (Page 137).

Observations:

- Gāndhāra artefacts (1, 2, 6) emphasize Buddhist themes with Hellenistic realism, using schist for intricate details.

- Mathurā artefacts (3, 4, 5) focus on Indian deities, with robust forms in red sandstone, reflecting local cultural dominance.

|

23 videos|204 docs|12 tests

|

FAQs on Class 7 Social Science Chapter 6 Let's Explore - The Age of Reorganisation

| 1. What were the main causes of the Age of Reorganisation? |  |

| 2. How did the Age of Reorganisation affect the map of Europe? |  |

| 3. What role did nationalism play during the Age of Reorganisation? |  |

| 4. Who were some key figures in the Age of Reorganisation, and what were their contributions? |  |

| 5. What were the social impacts of the Age of Reorganisation on ordinary people? |  |