Unit 1: Nature of Contracts - 2 Chapter Notes | Business Laws for CA Foundation PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Acceptance |

|

| Communication of Offer and Acceptance |

|

| Communication of Offer |

|

| Communication of Acceptance |

|

| Communication of Performance |

|

| Revocation of Offer and Acceptance |

|

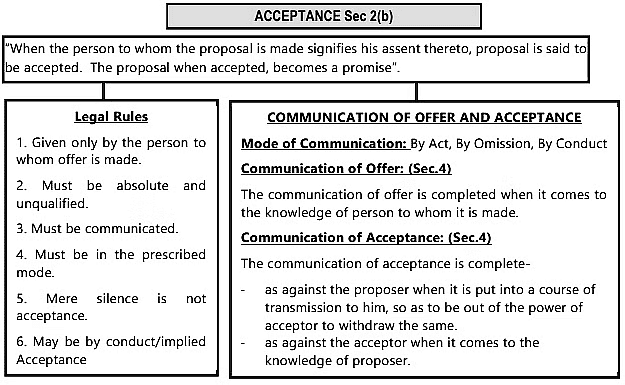

Acceptance

According to Section 2(b) of the Act, acceptance is defined as follows:“When the person to whom the proposal is made signifies his assent thereto, the proposal is said to be accepted. The proposal, when accepted, becomes a promise.”

Analysis of the Definition

- In this context, if A offers to sell his car to B for ₹ 2,00,000, the proposal is directed at B.

- If B agrees to this proposal, it indicates that B has signified his consent to A's offer.

- Once B signifies his consent, we conclude that the proposal has been accepted.

- An accepted proposal transforms into a promise.

Relationship Between Offer and Acceptance: As noted by Sir William Anson, “Acceptance is to offer what a lighted match is to a train of gun powder.” This suggests that acceptance initiates an irreversible process. However, the offeror can withdraw the offer before acceptance occurs. Once acceptance is made, it converts the offer into a promise, making withdrawal impossible. The analogy implies that while the offer (train of gun powder) is inactive by itself, it is the acceptance (lighted match) that activates it. This highlights that an offer alone does not establish a legal relationship; it is the acceptance by the offeree that does so. After an offer is accepted, it becomes a promise and cannot be revoked. Until acceptance occurs, an offer remains merely an offer but becomes a contract upon acceptance.

Legal Rules regarding a valid acceptance

Acceptance can be given only by the person to whom offer is made: In the case of a specific offer, it can only be accepted by the individual to whom it is addressed. [Boulton vs. Jones (1857)]

- Case Law: Boulton vs. Jones (1857)

Facts: Boulton purchased a business from Brocklehurst. Jones, a creditor of Brocklehurst, placed an order with Brocklehurst for certain goods. Boulton supplied the goods even though the order was not in his name. Jones refused to pay Boulton, asserting that his contract was with Brocklehurst and he intended to offset his debt against him.

Held: Since the offer was not directed to Boulton, no contract existed between Boulton and Jones. - In the case of a general offer: It can be accepted by anyone who is aware of the offer. [Carlill vs. Carbolic Smoke Ball Co. (1893)]

- Acceptance must be absolute and unqualified: According to Section 7 of the Act, acceptance is valid only when it is unequivocal and unqualified, expressed in a usual and reasonable manner unless the proposal specifies an acceptance method. If the proposal dictates an acceptance mode, it must be adhered to.

- M offered to sell his land to N for £280. N’s reply purported to accept the offer but included a cheque for £80 only, promising to pay the remaining £200 in monthly installments of £50. It was held that N could not enforce his acceptance as it was not unqualified. [Neale vs. Merret [1930] W. N. 189]

- A offers to sell his house to B for ₹30,00,000/-. B replies, “I can pay ₹24,00,000 for it.” This response from B is considered a rejection of A’s offer as it is not unqualified. If B later decides to offer ₹30,00,000/-, this is treated as a counter-offer, and it is up to A to accept it or not. [Union of India v. Bahulal AIR 1968 Bombay 294]

Example 51: ‘A’ asks ‘B’, “Will you purchase my car for ₹2 lakhs?” If ‘B’ responds, “I will buy your car for ₹2 lakhs if you buy my motorcycle for ₹50,000/-,” then ‘B’ has not accepted the offer. Conversely, if ‘B’ agrees to purchase the car from ‘A’ per his proposal, contingent on the availability of a valid Registration Certificate for the car, then acceptance is valid as it imposes no condition. Expecting a valid title is not a condition, making the acceptance unconditional. - The acceptance must be communicated: For a contract to be established between parties, acceptance must be communicated in a perceptible form. Any conditional acceptance or acceptance with varying terms constitutes no acceptance and is a counter-proposal needing proposer approval to form a contract. The offeree must also have knowledge of the offer to accept it. Acceptance must specifically relate to the original offer.

- Example 52: A proposed to B to marry him. B informed A’s sister that she is ready to marry him, but the sister did not communicate this to A. There is no contract because acceptance was not communicated to A.

- Acceptance must be in the prescribed mode: If the mode of acceptance is specified in the proposal, it must be accepted accordingly. If the proposer does not insist on this after an alternative acceptance, it’s presumed he has consented to the acceptance.

- Example 53: If the offeror requires acceptance via messenger and the offeree sends acceptance by email, there is no acceptance if the offeror informs the offeree that this method is not acceptable. However, if the offeror does not object, it is presumed that he accepted the acceptance, leading to a valid contract.

- Time: Acceptance must occur within any specified timeframe; if none is given, it must be within a reasonable time before the offer lapses. What constitutes reasonable time is not defined by law and depends on the specific case's facts and circumstances.

- Example 54: A offered to sell B 50 kgs of bananas at Rs. 500. B communicated acceptance after four days. This is an invalid contract since bananas, being perishable, could not remain fresh for a week. Four days is not reasonable in this instance.

- Example 55: A offers B to sell his house for Rs. 20,00,000. B accepted the offer and communicated it to A after four days. The contract is valid as four days is reasonable for a house sale.

- Mere silence is not acceptance: Acceptance of an offer cannot be inferred from the offeree's silence or failure to respond unless previous conduct indicates that silence constitutes acceptance.

- Case Law: Felthouse vs. Bindley (1862)

Facts: F (Uncle) offered to buy his nephew’s horse for £30, stating, “If I hear no more about it, I shall consider the horse mine at £30.” The nephew did not reply but instructed his auctioneer, B, to keep the horse unsold as he intended to reserve it for his uncle. By mistake, B sold the horse. F sued for conversion of property.

Held: F could not succeed as the nephew did not communicate acceptance to him. - Example 56: ’A’ subscribed to a weekly magazine for a year. Even after the subscription expired, the magazine company continued sending magazines for five years, and ‘A’ used them but denied payment for the bills. ‘A’ is liable to pay as his continued use of the magazine constitutes acceptance of the offer.

- Acceptance by conduct/Implied Acceptance: Section 8 of the Act states, “The performance of the conditions of a proposal or the acceptance of any consideration for a reciprocal promise offered with a proposal constitutes acceptance.” This section allows for acceptance by conduct, differing from verbal or written communication. When a person performs the act intended by the proposer as consideration, this performance constitutes acceptance.

- Example 57: When a tradesman receives an order from a customer and fulfills it by sending the goods, the customer’s order constitutes the offer, which the tradesman accepts by delivering the goods. This is an instance of acceptance by conduct.

Communication of Offer and Acceptance

The Role of Offer and Acceptance in Contract Validity

The significance of 'offer' and 'acceptance' in establishing a valid contract has been previously discussed. A crucial common requirement for both 'offer' and 'acceptance' is their effective communication. Proper communication helps avoid revocations and misunderstandings between the parties.

When parties are in face-to-face communication, issues of communication are minimal, as offers and acceptances occur instantly, eliminating concerns of revocation.

Challenges arise when parties are distant and use postal services, telephones, or emails. In these instances, knowing the precise timing of offer or acceptance is crucial.

The Indian Contract Act, 1872 emphasizes the "time" aspect in determining when an offer and acceptance are complete.

Communication of Offer

According to Section 4 of the Act, "the communication of offer is complete when it comes to the knowledge of the person to whom it is made".

Example 58: If 'A' sends an offer to 'B' by post to sell his house for ₹ 5 lakhs, and the letter is posted on 10th March and reaches 'B' on 12th March, the offer is communicated on 12th March when 'B' receives it. Thus, communication by post is complete when the recipient receives the letter. Merely receiving the letter is not enough; the recipient must read the message. If 'B' receives the letter on 12th March but reads it on 15th March, the offer is communicated on 15th March, not 12th March.

Communication of Acceptance

Two key issues are discussed regarding acceptance: the modes of acceptance and when acceptance is complete.

Modes of Acceptance

- Section 3 of the Act outlines two general modes of communication: (a) by any act and (b) by omission, both of which intend to communicate to the other party.

- Communication by act includes any expression of words, whether written (letters, telegrams, faxes, emails, advertisements) or oral (telephone messages). Additionally, communication can involve conduct intended to convey meaning through positive acts or signs.

- Acceptance can also occur by omission, where a person's failure to act indicates their willingness. However, silence does not qualify as communication by omission.

Example 59: If 'A' offers ₹ 50,000 to 'B' for not appearing in court as a witness, and 'B' does not appear, this omission constitutes acceptance.

Acceptance can also be communicated through conduct. For example, a seller delivering goods to a willing buyer conveys acceptance through that action. Similarly, boarding a public bus or dropping a coin in a weighing machine signifies acceptance of the respective service offers.

Effect of Communication

Indirect efforts must effectively communicate acceptance or non-acceptance; otherwise, there is no communication. A mere mental agreement does not count. For instance, a bank's resolution to sell land to 'A' without communicating it to 'A' does not result in a contract (Central Bank Yeotmal vs. Vyankatesh, 1949).

When is Communication of Acceptance Complete?

Section 4 of the Act states:

- As against the proposer, communication is complete when it is transmitted, removing the acceptor's ability to withdraw.

- As against the acceptor, it is complete when it comes to the proposer's knowledge.

If 'B' accepts 'A's proposal and sends acceptance by post on 14th, communication is complete for 'A' on 14th, when posted, and for 'B' when it reaches 'A'. 'A' is bound by 'B's acceptance once the letter is posted, regardless of postal delays. However, 'B' is only bound once 'A' receives the letter, leading to potential ambiguity if the letter is lost.

Acceptance via Instantaneous Communication

For instantaneous communication methods like telephone or email, a contract is only complete when acceptance is received by the proposer. The contract is formed at the location where acceptance is received (Entores Ltd. v. Miles Far East Corporation). Interruptions may invalidate the contract.

Communication of Special Conditions

Contracts may include special conditions, often implicitly accepted. Acceptance may occur without the parties' explicit awareness.

Example 60: A passenger accepts travel conditions printed on a ticket, regardless of whether they are aware of them. In Mukul Datta vs. Indian Airlines (1962), the court held that passengers are deemed to accept such conditions upon purchasing tickets.

Example 61: A launderer issues a receipt with special conditions, which are accepted by the customer's acceptance of the receipt (Lily White vs. R. Mannuswamy, 1966).

Case Law: Lilly White vs. Mannuswamy (1970)

Facts: P delivered clothes to a dry cleaner and received a receipt limiting liability for loss. P lost a saree and sought full compensation. The court ruled the terms were unreasonable, allowing P to recover full value. Acceptance of the document implied acceptance of the conditions.

Standard Forms of Contracts

Standard form contracts can be enforced against unaware parties if reasonable notice is provided. However, if the document's presentation does not reasonably alert the party to special conditions, they cannot be held to those conditions. For example, in Raipur Transport Co. vs. Ghanshyam (1956), a transport carrier's circular limiting liability was unenforceable as it wasn't communicated prior to the transport contract.

Communication of Performance

We have previously discussed that, according to Section 4 of the Act, communication of a proposal is considered complete when it reaches the knowledge of the intended recipient. Regarding the acceptance of the proposal, it can be analyzed from two perspectives:

- from the perspective of the proposer, and

- from the perspective of the acceptor.

From the proposer’s viewpoint, acceptance is complete when it is placed in a course of transmission, thus beyond the acceptor’s control. From the acceptor’s viewpoint, acceptance is complete once it is known to the proposer.

In some cases, the offeree may need to communicate their performance (or action) as a form of acceptance. Simply performing the act is insufficient unless the offer specifies that mere performance constitutes acceptance. This concept was illustrated in the well-known case of Carlill vs Carbolic & Smokeball Co. In this case, the defendant, a sole proprietorship manufacturing a medicine known as the carbolic ball, advertised the product and promised a reward of $100 to anyone who contracted influenza after using the medicine (referred to as 'carbolic smoke ball'). Mrs. Carlill purchased the smoke balls and used them as instructed but still contracted influenza. The court ruled that Mrs. Carlill was entitled to the $100 reward as she fulfilled the acceptance condition. Moreover, since the advertisement did not require communication of compliance, it was unnecessary to communicate her fulfillment of the condition. Consequently, the court established the following three key principles:

- an offer must include a clear promise from the offeror to be bound if the specified terms are accepted;

- an offer can be directed to a specific individual or to the general public; and

- if an offer is presented as a promise in exchange for an act, the act's performance, even without communication, is considered an acceptance of the offer.

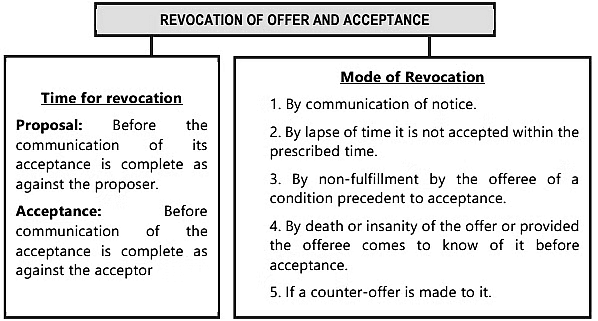

Revocation of Offer and Acceptance

If there are specific requirements governing the making of an offer and the acceptance of that offer, there are also specific laws governing their revocation.According to Section 4, communication of revocation (of the proposal or its acceptance) is complete:

- As against the person who makes it when it is put into a course of transmission to the person to whom it is made, so as to be out of the power of the person who makes it, and

- As against the person to whom it is made, when it comes to his knowledge.

The above law can be illustrated as follows: If you revoke your proposal made to me by a telegram, the revocation will be complete, as far as you are concerned when you have dispatched the telegram. However, as far as I am concerned, it will be complete only when I receive the telegram.

Regarding the revocation of acceptance, using the previous example, I can revoke my acceptance (of your offer) by a telegram. This revocation of acceptance by me will be complete when I dispatch the telegram, and against you, it will be complete when it reaches you.

The significant question for consideration is when a proposal can be revoked and when an acceptance can be revoked. These questions are more critical than the question of when the revocation (of the proposal and acceptance) is complete.

Ordinarily, the offeror can revoke his offer before it is accepted. If he does so, the offeree cannot create a contract by accepting the revoked offer.

Example 62: The bidder at an auction sale may withdraw (revoke) his bid (offer) before it is accepted by the auctioneer by the fall of the hammer. An offer may be revoked by the offeror before its acceptance, even if he had originally agreed to hold it open for a specific period. As long as it is merely an offer, it can be withdrawn whenever the offeror desires.

Example 63: X offered to sell 50 bales of cotton at a certain price and promised to keep it open for acceptance by Y until 6 pm that day. Before that time, X sold them to Z. Y accepted before 6 p.m., but after the revocation by X. In this case, it was held that the offer was already revoked.

According to Section 5 of the Act, a proposal can be revoked at any time before the communication of its acceptance is complete against the proposer. An acceptance may be revoked at any time before the communication of acceptance is complete against the acceptor.

Example 64: A proposes, by a letter sent by post, to sell his house to B. B accepts the proposal by a letter sent by post. A may revoke his proposal at any time before or at the moment when B posts his letter of acceptance, but not afterwards. Meanwhile, B may revoke his acceptance at any time before or at the moment when the letter communicating it reaches A, but not afterwards.

- An acceptance to an offer must be made before that offer lapses or is revoked.

- The law relating to the revocation of offers is the same in India as in England, but the law relating to the revocation of acceptance differs. In English law, the moment a person expresses his acceptance of an offer, a contract is concluded, and such acceptance becomes irrevocable, whether made orally or through post. In Indian law, the situation is different regarding contracts through post.

- Contract through post: In English law, acceptance cannot be revoked, so that once the letter of acceptance is properly posted, the contract is concluded. In Indian law, the acceptor can revoke his acceptance any time before the letter of acceptance reaches the offeror. If the revocation telegram arrives before or at the same time with the letter of acceptance, the revocation is absolute.

- Contract over Telephone: A contract can be made over the telephone. The rules regarding offer and acceptance, as well as their communication by telephone or telex, are the same as those for contracts made by the mutual meeting of the parties. The contract is formed as soon as the offer is accepted, but the offeree must ensure that his acceptance is received by the offeror; otherwise, there will be no contract, as communication of acceptance is not complete. If the telephone unexpectedly goes dead during conversation, the acceptor must confirm again that the words of acceptance were duly heard by the offeror.

- Revocation of proposal otherwise than by communication: When a proposal is made, the proposer may not wait indefinitely for its acceptance. The offer can be revoked otherwise than by communication or sometimes by lapse.

Modes of revocation of offer:

- By notice of revocation:

Example 65: A offered B to sell goods at Rs. 5,000 through post, but before B could accept the offer, A received the highest bid for the goods from C. So, A revoked the offer to B by informing B over the telephone and sold the goods to C. - By lapse of time: The time for acceptance can lapse if acceptance is not given within the specified time, and where no time is specified, then within a reasonable time. This is because the proposer should not be made to wait indefinitely. It was held in Ramsgate Victoria Hotel Co. Vs Montefiore (1866 L.R.Z. Ex 109) that a person who applied for shares in June was not bound by an allotment made in November. This decision was also followed in India Cooperative Navigation and Trading Co. Ltd. Vs Padamsey Prem Ji. However, these decisions will no longer be relevant in the context of allotment of shares since the Companies Act, 2013 has several provisions specifically addressing these issues.

- By non-fulfillment of condition precedent: Where the acceptor fails to fulfill a condition precedent to acceptance, the proposal gets revoked. This principle is laid down in Section 6 of the Act. The offeror, for instance, may impose certain conditions such as executing a certain document or depositing a certain amount as earnest money. Failure to satisfy any condition will result in the lapse of the proposal. As stated earlier, a ‘condition precedent’ to acceptance prevents an obligation from coming into existence until the condition is satisfied. Suppose A proposes to sell his house to B for ₹ 5 lakhs provided B leases his land to A. If B refuses to lease the land, A's offer is revoked automatically.

- By death or insanity: Death or insanity of the proposer would result in the automatic revocation of the proposal, but only if the fact of death or insanity comes to the knowledge of the acceptor.

- By counter offer

- By the non-acceptance of the offer according to the prescribed or usual mode

- By subsequent illegality.

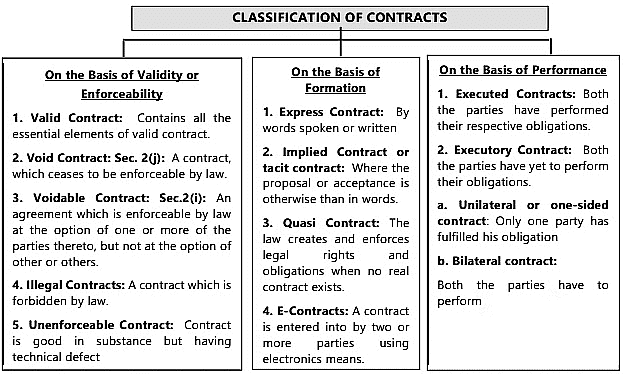

Summary

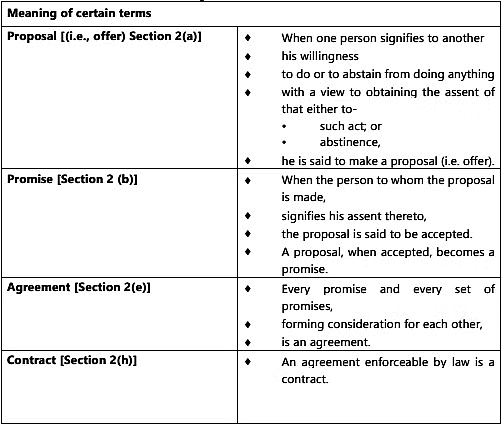

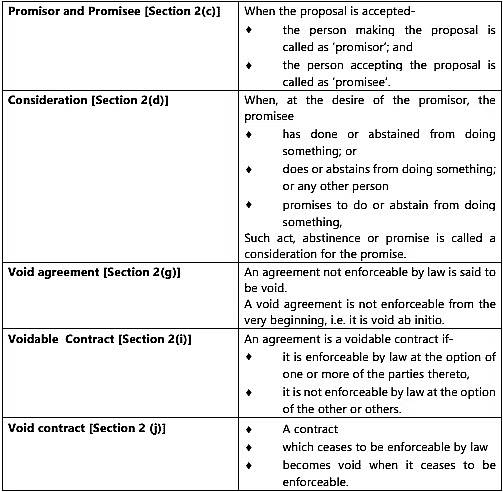

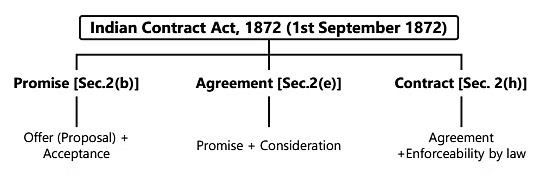

Contract: A Contract is a legally enforceable agreement [Section 2(h)]. An agreement is enforceable by law if it is created with the free consent of competent parties, has a lawful object, involves lawful consideration, and is not explicitly declared void [Section 10]. All contracts are agreements, but not all agreements qualify as contracts. Agreements that lack any of these characteristics are not considered contracts. A contract that is no longer enforceable by law is termed a ‘void contract’ [Section 2(i)], while an agreement enforceable at the option of one party but not the other is termed a ‘voidable contract’ [Section 2(i)].

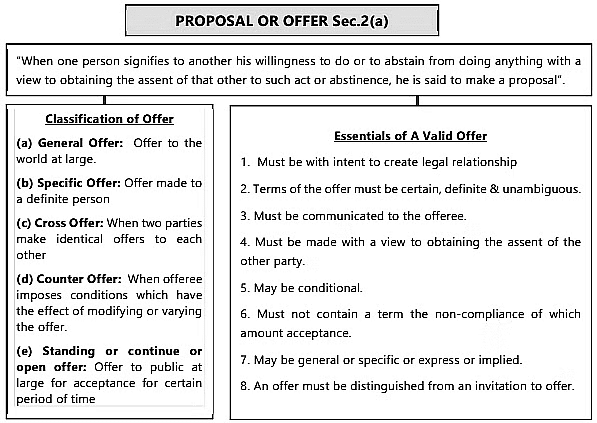

Offer and Acceptance: The offeror commits to performing or refraining from a specific act if the offer is accepted properly by the offeree. An offer can be made explicitly or implicitly through the offeror's actions, but it must demonstrate intention and the ability to create legal relations. The terms of the offer must be definite or at least capable of being made definite.

Acceptance of the offer must be unequivocal and must follow the prescribed or usual method. If the offer is directed to a specific individual, only that person can accept it; however, a general offer can be accepted by anyone.

Communication of Offer and Acceptance, and Revocation:

- Communication of an offer is complete when the offeree becomes aware of it.

- Communication of acceptance is complete: against the offeror when it is transmitted and against the acceptor when the offeror is aware of it.

- Communication of revocation of an offer or acceptance is complete: against the person revoking when it is sent out of their control and against the recipient when they become aware of it.

Note: Agreement may be social or legal. Social Agreement is not enforceable by law.

|

32 videos|185 docs|57 tests

|

FAQs on Unit 1: Nature of Contracts - 2 Chapter Notes - Business Laws for CA Foundation

| 1. What is the definition of acceptance in the context of contracts? |  |

| 2. How is an offer communicated and what are the essential elements? |  |

| 3. Can an offer be revoked after acceptance has occurred? |  |

| 4. What is the significance of communication of performance in contracts? |  |

| 5. What happens if an offer is revoked before acceptance? |  |