Short Notes: Unit 2: Theory of Consumer Behaviour | Business Economics for CA Foundation PDF Download

All economic activity begins with human wants. These wants are our wishes to get things like food, clothes, phones, or services that make us happy or comfortable. People want things for many reasons – to meet basic needs, feel good, or look good in society. Even though we can satisfy some of our wants, new wants keep coming. But the problem is that we have only limited money and resources. So, we must choose which wants are more important. This is why understanding human wants helps us know how people make decisions, how they get satisfaction (called utility), and how they spend their money.

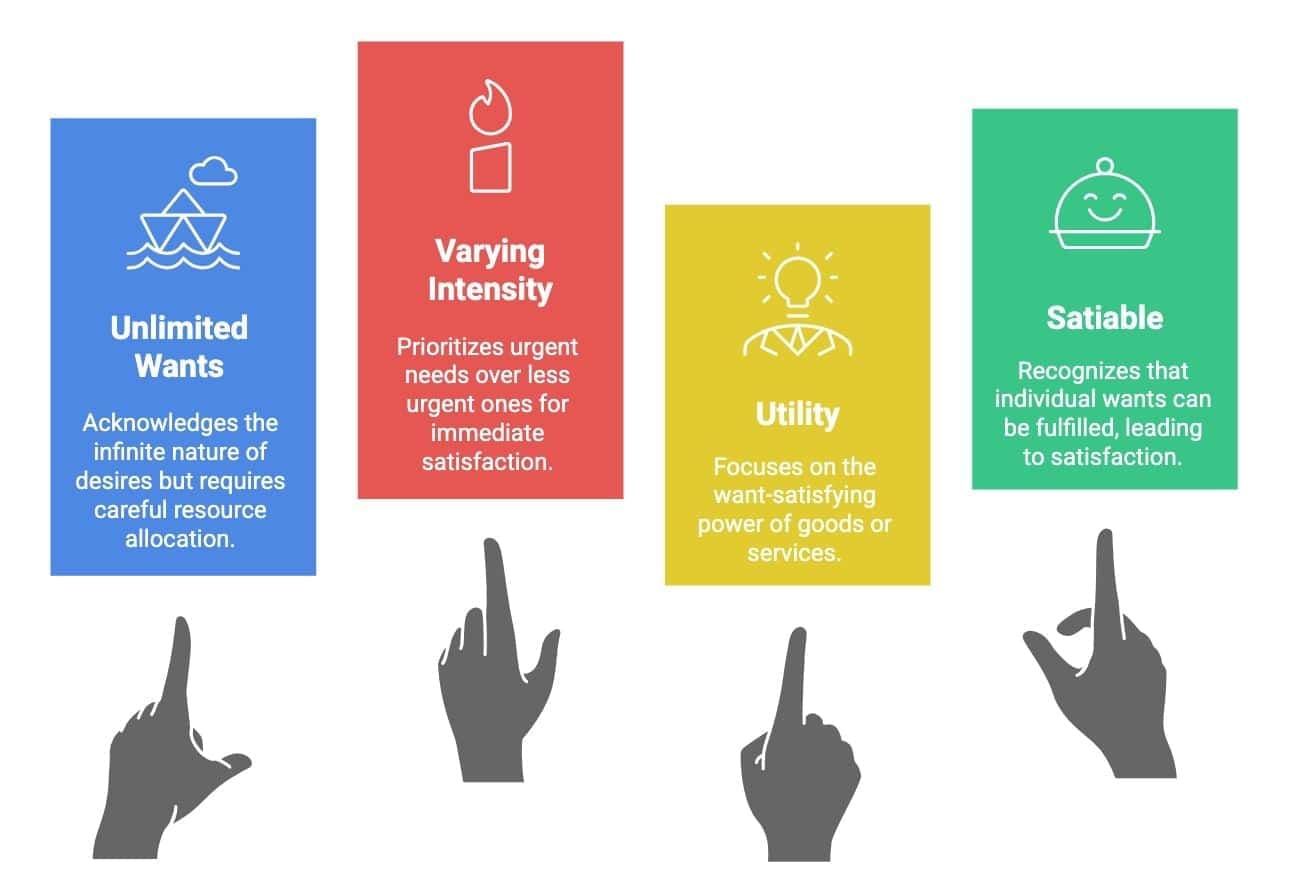

Nature of Human Wants

Wants are desires to acquire goods or services for satisfaction, driven by physical, psychological, or social factors. Due to limited resources, consumers prioritize urgent wants over less urgent ones.

- Unlimited: Wants are infinite, but resources are scarce, requiring choices.

- Varying Intensity: Some wants are urgent, others less so.

- Utility: The want-satisfying power of a commodity.

- Satiable: Individual wants can be fulfilled.

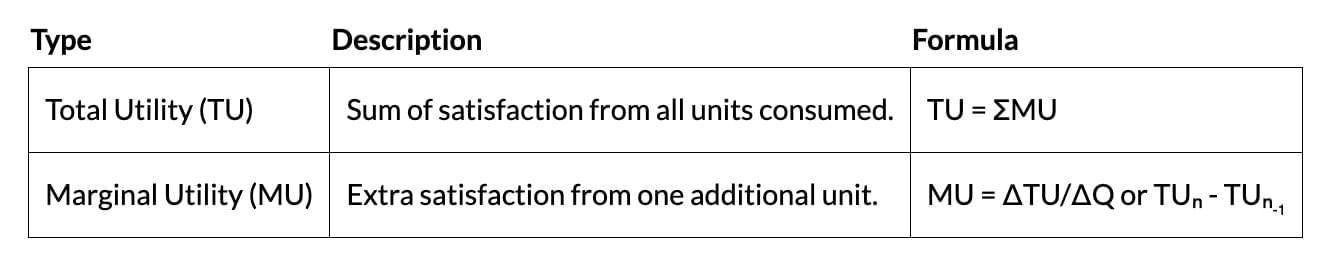

Utility

Utility is the psychological satisfaction derived from consuming goods, distinct from usefulness. It is subjective and varies by individual.

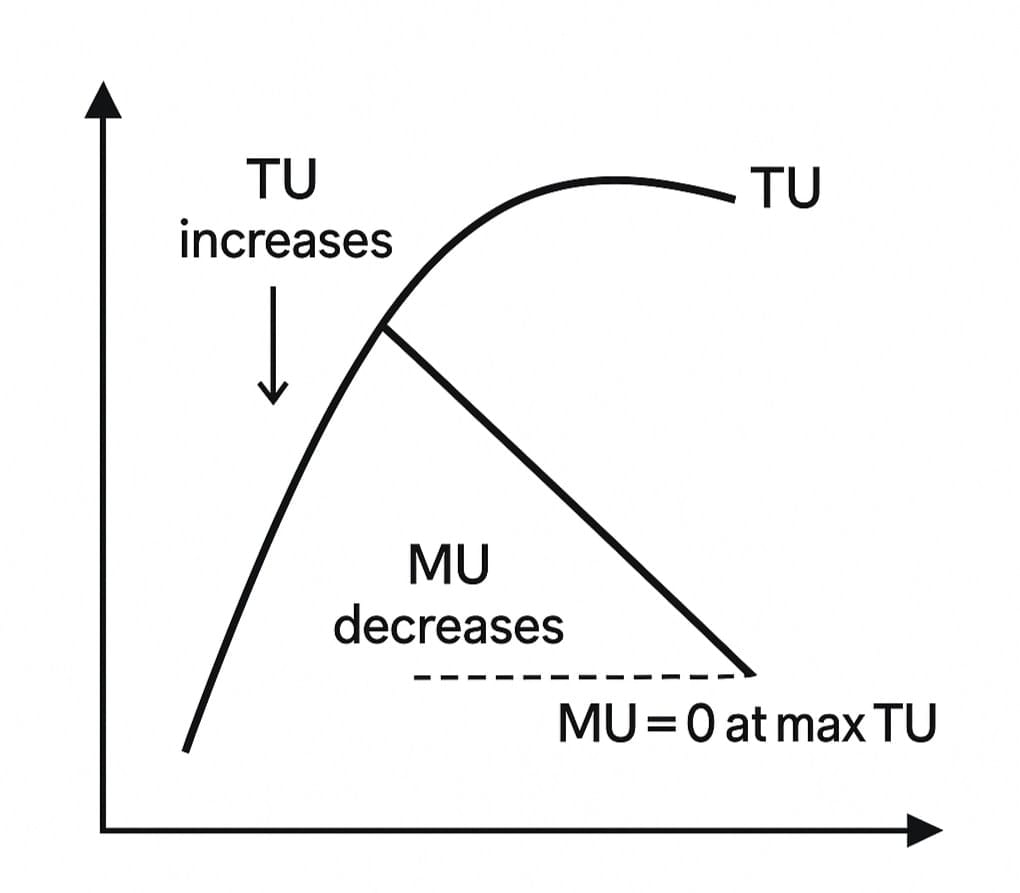

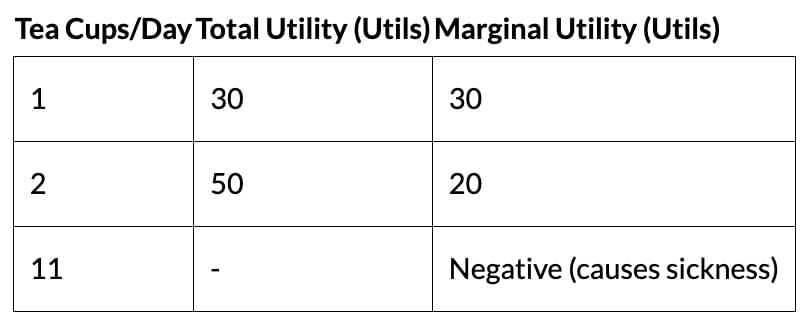

Relationship between TU and MU: TU increases at a decreasing rate as MU declines. When TU is maximum, MU = 0; when TU decreases, MU becomes negative.

TU increases, MU decreases; MU = 0 at max TU.

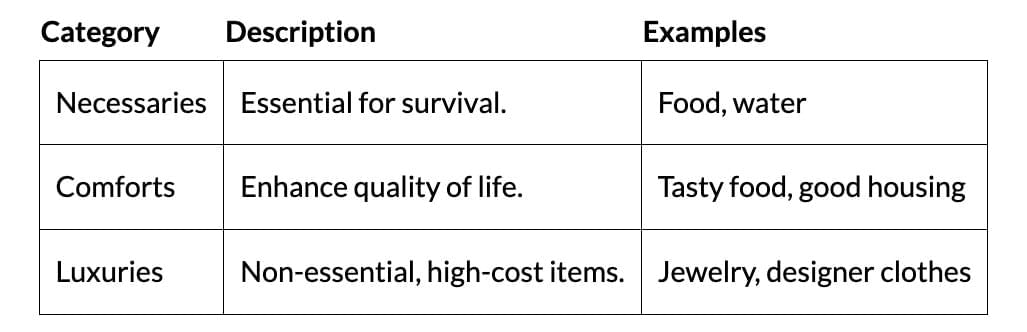

TU increases, MU decreases; MU = 0 at max TU.Classification of Wants

Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

As a consumer consumes more units of a good, the additional satisfaction (MU) from each unit decreases.

Assumptions: Identical units, unchanged consumer habits/tastes/income, standard units, continuous consumption. Not applicable to goods like gold.

MU decreases as consumption increases.

MU decreases as consumption increases.Consumer Surplus

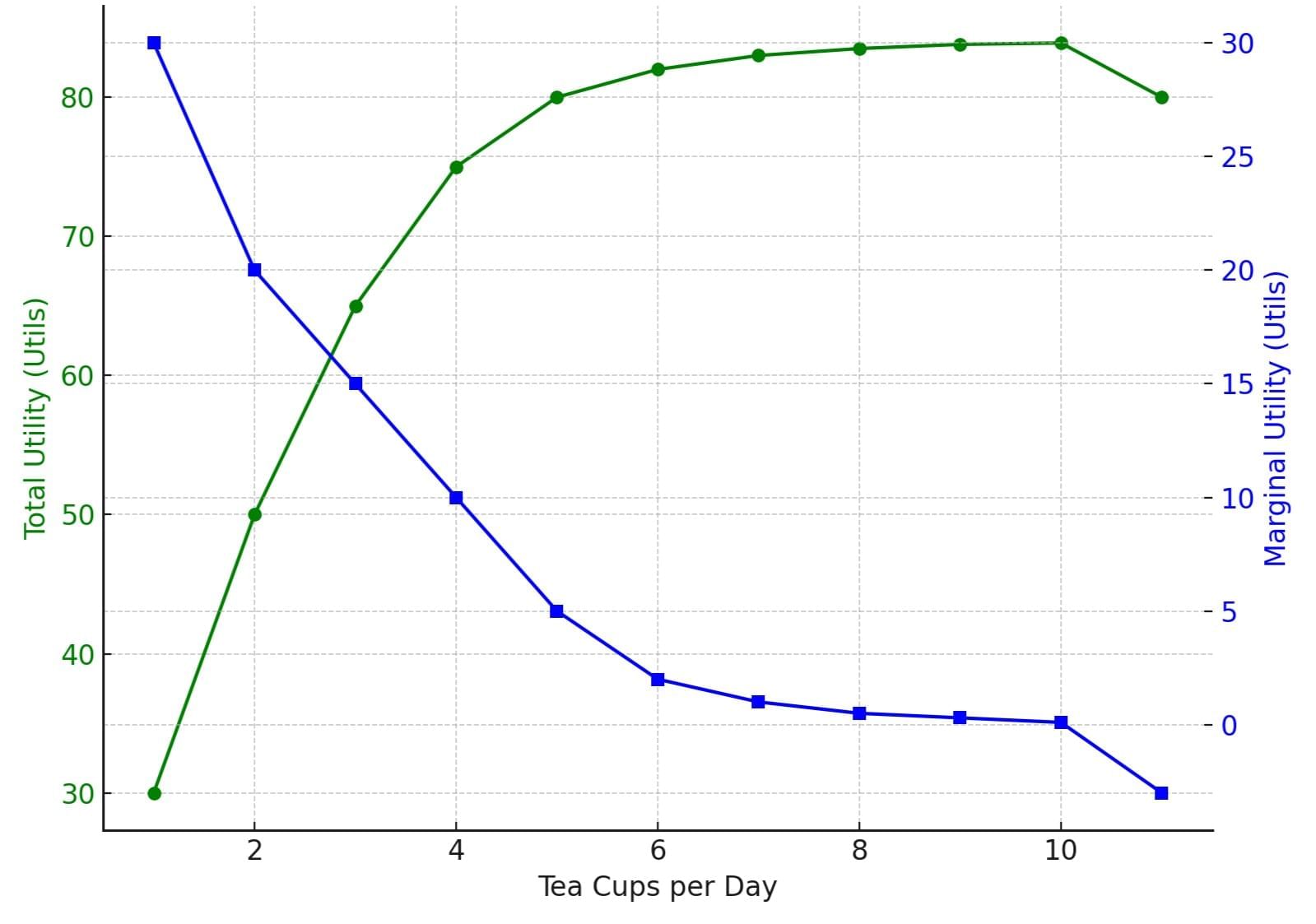

Consumer surplus is the difference between what consumers are willing to pay and what they actually pay, reflecting net benefits from purchases.

Formula: Consumer Surplus = Willingness to Pay - Actual Payment

- Origin: Based on diminishing MU; surplus arises when MU > price.

- Graphical Representation: Triangular area below demand curve, above price line.

- Price Impact: Higher prices reduce surplus; lower prices increase it, benefiting existing and new buyers.

Consumer surplus as the area DPR above price OP.

Consumer surplus as the area DPR above price OP.Applications:

- Guides pricing and price discrimination.

- Supports cost-benefit analysis for investments.

- Informs tax policies (tax high-surplus goods to minimize welfare loss).

Limitations: Difficult to quantify due to subjective utility; infinite for essentials; affected by substitutes; assumes constant marginal utility of money.

Indifference Curve Analysis

An ordinal utility approach that ranks preferences without quantifying satisfaction, using indifference curves to show combinations of two goods yielding equal satisfaction.

Assumptions:

- Consumers know preferences and act rationally.

- Utility is ordinal; preferences are transitive.

- More goods are preferred (non-satiation).

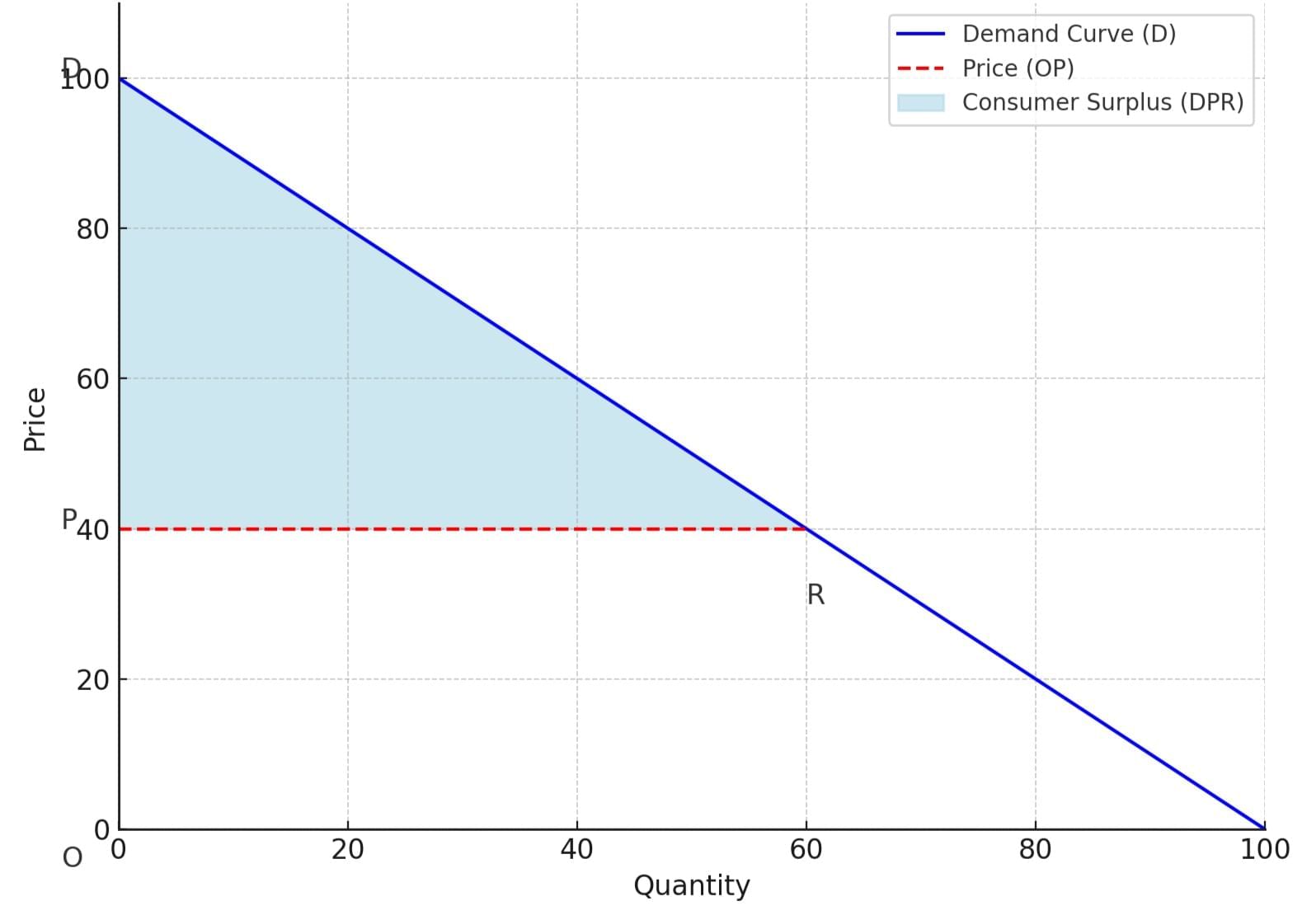

Properties of Indifference Curves:

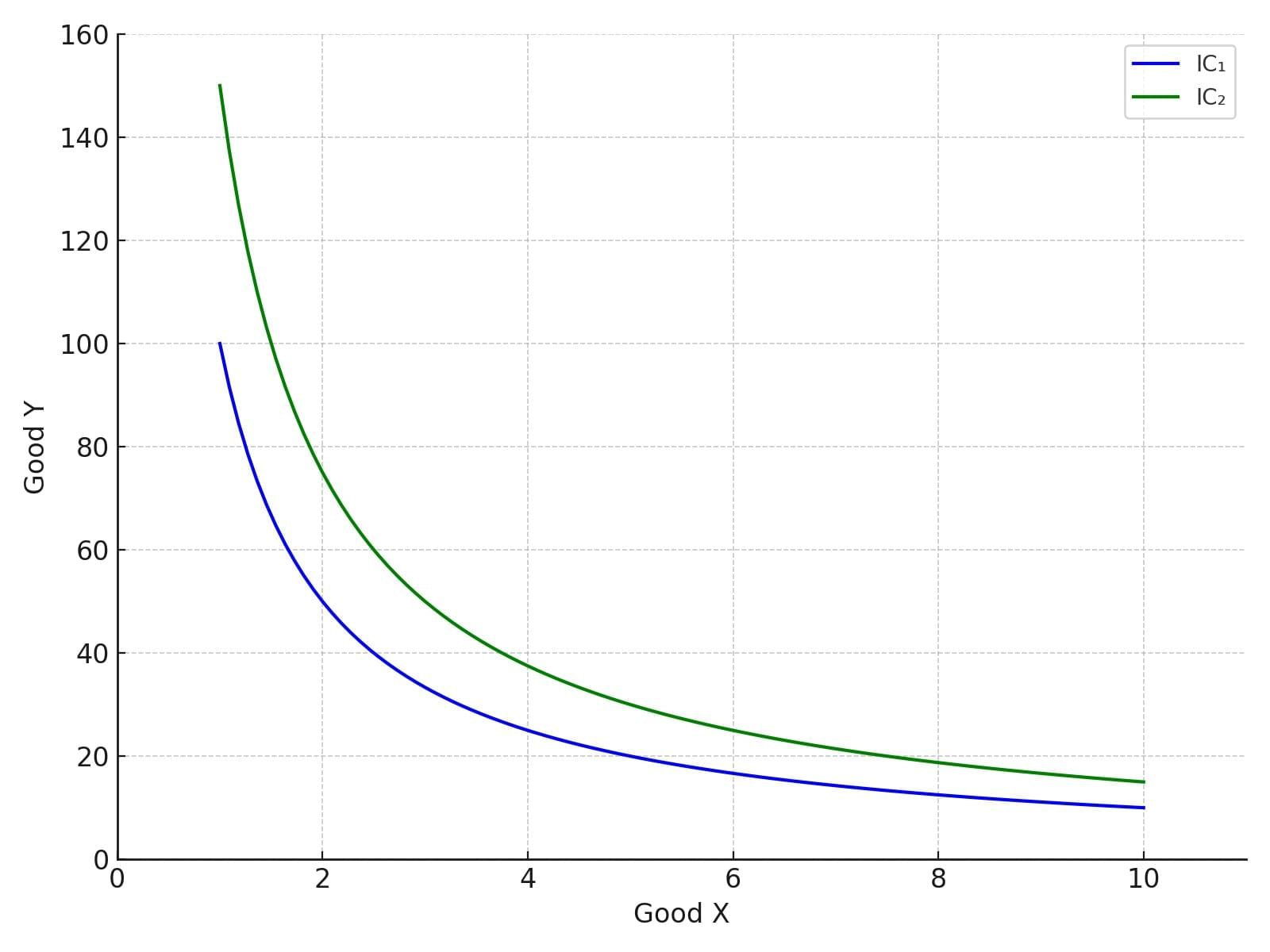

Higher indifference curves (IC₂) yield more satisfaction than lower ones (IC₁).

Higher indifference curves (IC₂) yield more satisfaction than lower ones (IC₁).

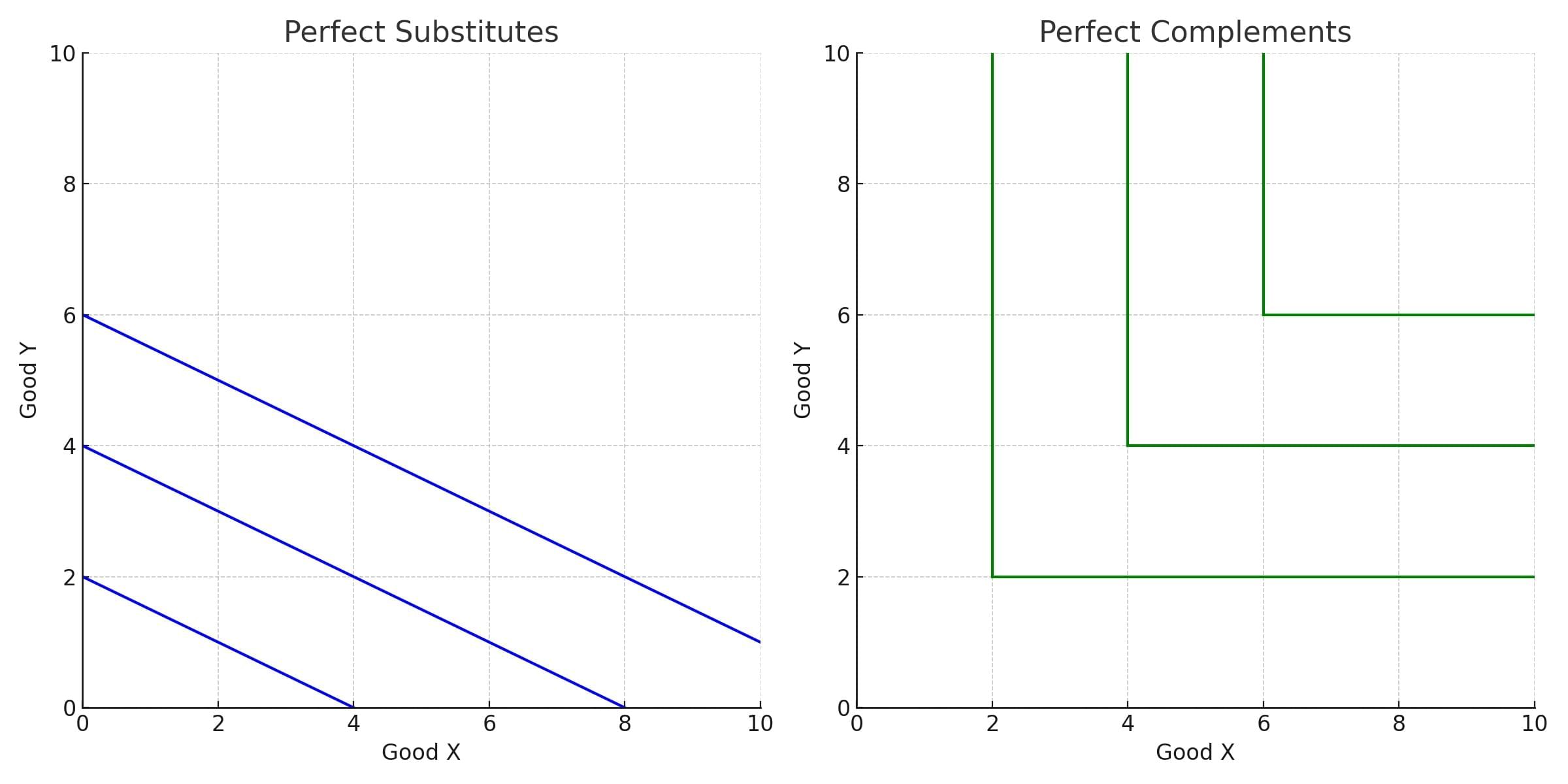

Special Cases:

- Perfect Substitutes: Straight, parallel lines (constant MRS).

- Perfect Complements: L-shaped curves (fixed proportions, e.g., left and right shoes).

Straight Lines for substitutes and L shaped for complements

Straight Lines for substitutes and L shaped for complements

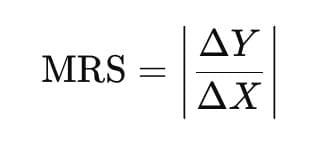

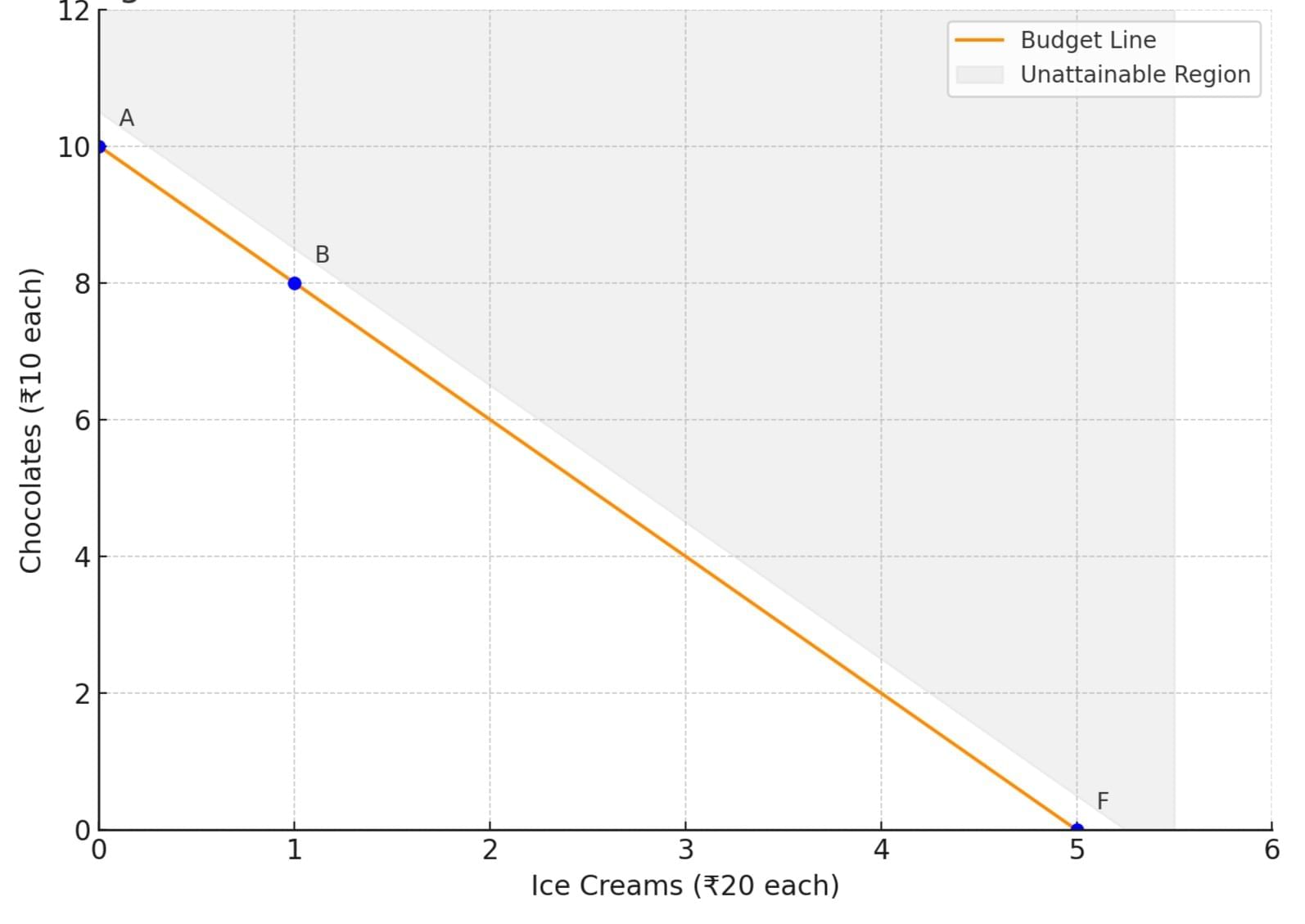

Marginal Rate of Substitution (MRS)

MRS is the rate at which a consumer is willing to give up units of good Y to gain an additional unit of good X, while keeping their level of satisfaction constant.

Formula:

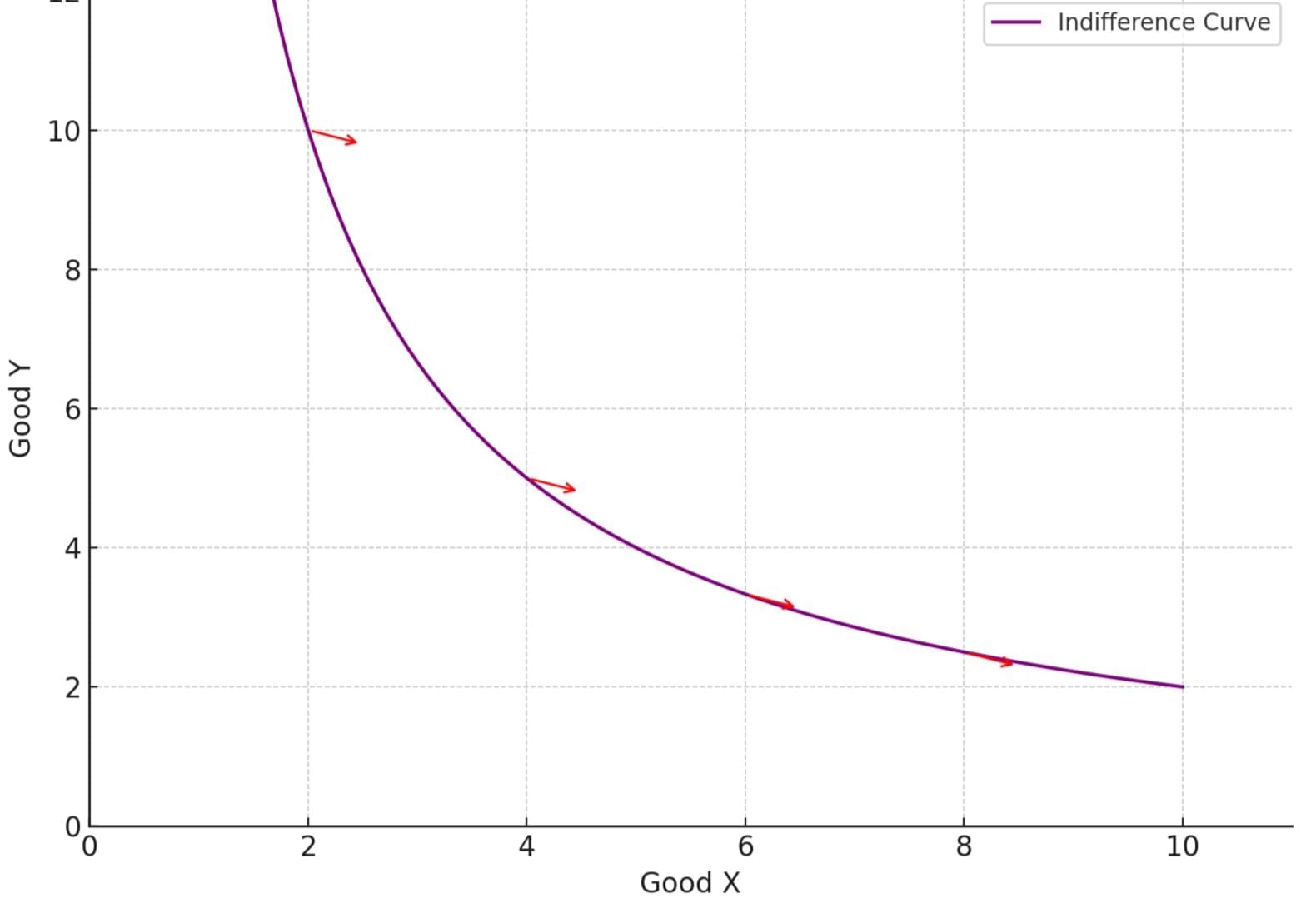

Diminishing MRS: As the consumer consumes more of good X, they are willing to give up less of good Y to get one more unit of X — indicating a declining willingness to substitute Y for X.

Example: Initially: 6 units of clothing (Y) traded for 1 unit of food (X)

Later: Only 2 units of clothing for 1 unit of food

This reflects diminishing marginal utility and a convex indifference curve.

MRS decreases along the indifference curve.

MRS decreases along the indifference curve.Budget Line

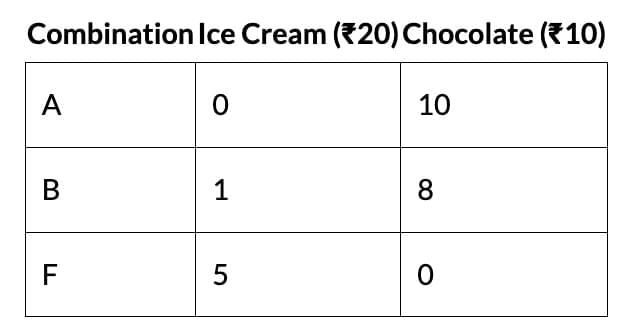

A budget line represents all possible combinations of two goods that a consumer can afford, given their income and the prices of the goods.

Equation: PₓQₓ + PᵧQᵧ = B

(Pₓ, Pᵧ: prices; Qₓ, Qᵧ: quantities; B: budget).

Slope: Price ratio (Pₓ/Pᵧ), This shows the rate at which the consumer can trade one good for the other, based on their relative prices.

Shifts:

If income changes (prices constant): The line shifts parallelly—rightward for higher income, leftward for lower.

If prices change (income constant): The slope changes, altering the trade-off and tilting the line.

Budget line shows affordable combinations; points outside are unattainable.

Budget line shows affordable combinations; points outside are unattainable.Consumer Equilibrium

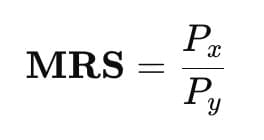

Consumer’s equilibrium occurs when a consumer maximizes satisfaction given their budget constraint.

Conditions for Consumer Equilibrium:

- Entire Income is Spent: The consumer allocates their entire budget on the purchase of goods X and Y.

- Prices are Constant: The prices of both goods remain fixed, and goods are perfectly divisible.

- Rational Behavior: The consumer aims to achieve maximum utility based on preferences.

Equilibrium Condition:

At equilibrium, the consumer chooses the point where:

This occurs where the budget line is tangent to the highest attainable indifference curve.

Equilibrium at tangency of budget line and highest indifference curve.

Equilibrium at tangency of budget line and highest indifference curve.

|

86 videos|200 docs|58 tests

|

FAQs on Short Notes: Unit 2: Theory of Consumer Behaviour - Business Economics for CA Foundation

| 1. What are the different classifications of human wants in economic theory? |  |

| 2. What is the concept of utility in consumer behavior? |  |

| 3. How does the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility affect consumer choices? |  |

| 4. What is consumer surplus and why is it important in economics? |  |

| 5. What is an indifference curve and how does it illustrate consumer equilibrium? |  |