Summary: Nature of Contracts | Business Laws for CA Foundation PDF Download

Introduction

The Indian Contract Act, 1872, enacted on April 25, 1872, is a cornerstone of mercantile law, governing contracts essential to trade, commerce, and industry. Before its implementation, English law applied in Presidency Towns (Madras, Bombay, Calcutta) under the Charter of 1726, with justice, equity, and good conscience guiding decisions elsewhere. The Act codifies principles for legally enforceable contracts, covering essentials of valid contracts and special relationships like indemnity, guarantee, bailment, pledge, quasi-contracts, and contingent contracts.

What is a Contract?

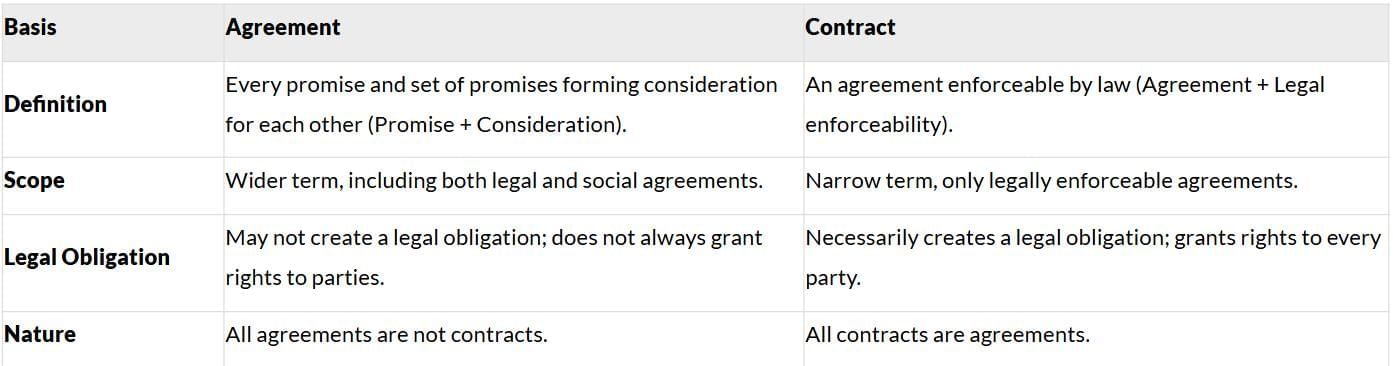

Per Section 2(h), a contract is "an agreement enforceable by law," comprising:

Agreement: Section 2(e) defines it as "every promise and every set of promises, forming the consideration for each other." A promise, per Section 2(b), is a proposal accepted by the offeree.

Enforceability by Law: An agreement must create a legal obligation. Social agreements, like a father promising pocket money to his son, are not contracts due to a lack of legal intent (e.g., Balfour v. Balfour). Example: A agrees to sell a car to B for ₹2 lakh, creating mutual obligations enforceable by law.

An agreement arises from a proposal and acceptance with consideration, but it becomes a contract only when it is legally enforceable, creating legal obligations. Social or moral agreements (e.g., a promise to pay pocket money) are not contracts due to a lack of legal intent. All contracts are agreements, but not all agreements are contracts.

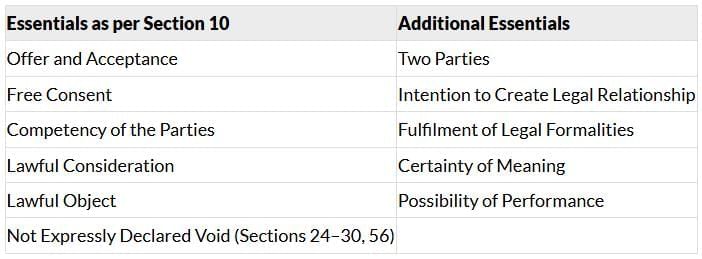

Explanation of Essential Elements of a Valid Contract

- Offer and Acceptance: A contract begins with a proposal (offer) from one party, accepted by another, forming an agreement (Section 2(e)). The offer must be clear, and acceptance must be absolute, creating a promise (Section 2(b)).

- Free Consent: Consent is free when not caused by coercion, undue influence, fraud, misrepresentation, or mistake (Section 14). Parties must agree on the same thing in the same sense (consensus ad idem). Example: No contract if A sells a red car, but B thinks it’s a black car.

- Capacity of the Parties: Per Section 11, parties must be of legal age, of sound mind, and not disqualified (e.g., minors, lunatics, or convicts cannot contract unless fulfilling specific legal formalities).

- Lawful Consideration: Consideration is "quid pro quo" (something in return), involving a right, interest, or benefit to one party or forbearance, detriment, or loss to another (Section 2(d)). It must be lawful, not prohibited or immoral.

- Lawful Object: The object must not be prohibited, fraudulent, injurious, immoral, or against public policy (Section 23). Example: An agreement to sell cocaine is void.

- Not Expressly Declared Void: Agreements in restraint of trade, marriage, or legal proceedings are void (Sections 24–30, 56).

- Two Parties: A contract requires an offeror and acceptor; one cannot contract with oneself.

- Intention to Create Legal Relationship: Parties must intend legal consequences. Social agreements (e.g., a husband’s promise to pay maintenance) are not contracts.

- Legal Formalities: Certain contracts (e.g., insurance, immovable property) require writing or registration for enforceability.

- Certainty of Meaning: Terms must be unambiguous to ensure mutual understanding.

- Possibility of Performance: The agreement must be performable. Example: An agreement to discover treasure by magic is void.

Types of Contracts

Contracts are classified based on validity, formation, and performance, with detailed explanations below.

Based on Validity

- Valid Contract: An agreement meeting all essentials, binding and enforceable. Example: A agrees to sell a bike to B for ₹50,000, enforceable by law.

- Void Contract: Per Section 2(j), a contract that ceases to be enforceable due to impossibility or change in law (e.g., promisor’s death or factory fire destroying goods).

- Voidable Contract: Per Section 2(i), enforceable at one party’s option due to lack of free consent (e.g., coercion) or failure to perform within time. Example: X sells a scooter to Y under duress; X can void it.

- Illegal Contract: Forbidden by law, always void, with collateral agreements also void. Example: An agreement to deal in drugs.

- Unenforceable Contract: Valid in substance but unenforceable due to technical defects (e.g., barred by limitation or lack of registration). Example: A debt unpaid after three years.

Based on Formation

- Express Contract: Terms are stated in words, spoken or written. Example: A written agreement to sell goods.

- Implied/Tacit Contract: Formed by conduct or implication, not words (Section 9). Example: A coolie carrying luggage without being asked, with A allowing it, implies a contract.

- Quasi-Contract: Not a true contract but imposed by law to enforce obligations without intent. Example: The Finder of lost goods must return them.

- E-Contract: Formed electronically via digital means (e.g., online purchases, mouse-click contracts).

Based on Performance

- Executed Contract: Both parties have fulfilled obligations. Example: A grocer sells sugar for cash payment.

- Executory Contract: Obligations remain to be performed.

1. Unilateral Contract: One party has performed, and the other’s obligation is pending. Example: M offers ₹50,000 for finding a missing boy; B finds him, but M must pay.

2. Bilateral Contract: Both parties’ obligations are pending. Example: A gives a plot to B, who pays ₹2.5 lakh and promises the balance later.

Proposal/Offer

A proposal is when one person signifies willingness to do or abstain from doing something to obtain another’s assent (Section 2(a)). It is the starting point of a contract, expressing intent to create legal relations. It can be positive (doing an act, e.g., selling a car) or negative (abstaining, e.g., not suing for damages). The offeror (promisor) makes the offer to the offeree, who becomes the acceptor (promisee) upon acceptance.

Essentials of a Valid Offer

- Must be capable of creating legal relations: The offer must intend legal consequences, not social invitations (e.g., a birthday party invitation is not an offer).

- Terms of the offer must be certain, definite, and unambiguous: The offer must be clear to avoid misunderstanding.

- Must be communicated to the offeree: An offer is ineffective until known by the offeree.

- Must be made to obtain the assent of the other party: The offer aims to secure agreement, not merely state intentions.

Types of Offer

- General Offer: Made to the public at large, accepted by anyone fulfilling conditions (e.g., a reward for finding lost items).

- Specific Offer: Made to a definite person; only that person can accept.

- Cross Offer: Two parties make identical offers simultaneously, unaware of each other’s offer, resulting in no contract.

- Counter Offer: A modified acceptance, rejecting the original offer. Example: A offers a plot for ₹10 lakh; B agrees to pay ₹8 lakh.

- Standing/Continuing/Open Offer: Remains open for acceptance over time (e.g., tenders for goods supply).

Acceptance

Acceptance is when the offeree signifies assent to the proposal, converting it into a promise (Section 2(b)). It creates a binding agreement when absolute and communicated properly.

Legal Rules for a Valid Acceptance

Per Section 2(b) of the Indian Contract Act, 1872, acceptance is defined as when the person to whom a proposal is made signifies their assent thereto, converting the proposal into a promise. The following seven legal rules, as outlined in the PDF, ensure a valid acceptance:

- Given only by the person to whom the offer is made: The acceptance must come from the offeree or their authorised agent to whom the proposal is directed.

- Must be absolute and unqualified: The acceptance must fully agree with the terms of the proposal without any modifications or conditions.

- Must be communicated: The offeree must convey their assent to the offeror, whether through words, actions, or another mode, to make the acceptance effective.

- Must be in the prescribed mode: If the proposal specifies a mode of acceptance (e.g., by post or messenger), it must be followed; otherwise, a usual and reasonable manner applies. If the offeror does not object to a different mode, they are presumed to have consented to it.

- Time: Acceptance must be given within the specified time in the proposal or, if no time is prescribed, within a reasonable time.

- Mere silence is not acceptance: Silence or failure to respond does not constitute acceptance unless the offeree’s prior conduct indicates that silence signifies assent.

- May be by conduct/implied acceptance: Acceptance can occur through the performance of the proposal’s conditions or actions (Section 8), such as delivering goods or fulfilling a task offered, without explicit verbal or written communication.

Communication of Offer and Acceptance

The Indian Contract Act, 1872, emphasises the importance of the "time" element in determining when the communication of an offer and acceptance is complete, as outlined in Section 4 and related provisions. Effective communication prevents misunderstandings and avoidable revocations between parties.

Communication of Offer (Section 4): The communication of an offer is complete when it comes to the knowledge of the person to whom it is made. For example, if a proposal is sent by post, it is complete when the offeree receives and reads the letter, not merely when it is delivered.

Communication of Acceptance (Section 4): The communication of acceptance is complete in two stages:

As against the proposer: When the acceptance is put into a course of transmission to the proposer, to be out of the power of the acceptor to withdraw (e.g., when a letter of acceptance is posted).

As against the acceptor: When the acceptance comes to the knowledge of the proposer (e.g., when the proposer receives the letter).Modes of Communication: Communication can occur through acts, omissions, or conduct. For instance, delivering goods at a price to a willing buyer or boarding a public bus conveys acceptance by conduct. In instantaneous communication (e.g., telephone, fax, or email), the contract is complete only when the acceptance is received by the offeror.

Communication of Special Conditions: Special conditions, such as those printed on tickets (e.g., travel terms), are deemed communicated and accepted upon purchase, even if the offeree is unaware, provided the notice is reasonable.

Communication of Performance (Section 8): When an offer requires performance of a condition as acceptance, the act itself constitutes acceptance. Communication of performance is necessary unless the offer specifies that performance alone suffices. For example, performing an act like delivering goods may not require further communication if the offer allows it.

Communication of Performance

- Section 8 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 states that fulfilling the conditions of a proposal is considered acceptance.

- This means that when the offeree does what was asked in the offer, such as finding lost items or delivering promised goods, it is seen as a valid acceptance.

- The communication of this performance is sufficient unless the offer specifically requires the offeree to inform the offeror.

- This rule in Indian Contract Law ensures that acceptance through performance is effective when the actions match the offer's terms.

- It offers flexibility while keeping the offeror informed, particularly in cases involving rewards or conditions where the action itself signifies agreement.

Revocation of Offer and Acceptance

Section 4 of the Act defines when the communication of a proposal, acceptance, or revocation is complete, which is foundational to understanding revocation timing.

Communication of a Proposal: The communication of a proposal is complete when it comes to the knowledge of the person to whom it is made. For example, a letter of proposal is considered communicated when received and read by the offeree.

Communication of an Acceptance: The communication of an acceptance is complete:

(a) As against the proposer: When it is put into a course of transmission to him, to be out of the power of the acceptor (e.g., when a letter of acceptance is posted).

(b) As against the acceptor: When it comes to the knowledge of the proposer (e.g., when the letter is received by the proposer).Relevance to Revocation: This section establishes that revocation must occur before the acceptance is complete against the proposer for the offer to be effectively withdrawn, linking it to the timing rules in Section 5.

Section 5: Revocation of Proposals and Acceptances

Section 5 specifies the conditions under which a proposal or acceptance can be revoked, providing the legal framework for termination before a contract is binding.

Revocation of Proposal: A proposal may be revoked at any time before the communication of its acceptance is complete as against the proposer. This means the offeror can withdraw the offer before the acceptance is transmitted (e.g., before the acceptance letter is posted).

Revocation of Acceptance: An acceptance may be revoked at any time before the communication of the acceptance is complete as against the acceptor. This allows the offeree to retract acceptance before it reaches the proposer (e.g., by sending a revocation telegram that arrives before or with the acceptance letter).

Indian Law Perspective: Unlike English law, where acceptance by post is generally irrevocable once posted, Indian law permits revocation of acceptance if the revocation reaches the offeror before or simultaneously with the acceptance, offering greater flexibility to the offeree.

Modes of Revocation (Section 6):

- By communication of notice: The offeror explicitly revokes the offer (e.g., A informs B over the phone before B accepts).

- By lapse of time: The offer lapses if not accepted within the specified or reasonable time.

- By non-fulfilment of a condition precedent: Failure to meet conditions (e.g., depositing earnest money) revokes the offer.

- By death or insanity of the offeror: Revocation occurs if the offeree knows of the death or insanity before acceptance.

- By counter-offer: A modified acceptance rejects the original offer.

- By non-acceptance according to the prescribed mode: If acceptance deviates from the specified method, the offer may lapse.

|

32 videos|185 docs|57 tests

|

FAQs on Summary: Nature of Contracts - Business Laws for CA Foundation

| 1. What are the essential elements required for a valid contract? |  |

| 2. What is the difference between a proposal and an acceptance in contract law? |  |

| 3. How is the communication of offer and acceptance significant in forming a contract? |  |

| 4. What does revocation of offer and acceptance mean in contract law? |  |

| 5. What are the different types of contracts, and how do they differ? |  |