Motion Of A Particle In Two Or More Dimensions | Basic Physics for IIT JAM PDF Download

Projectile motion:

Galileo was quoted above pointing out with some detectable pride that none before him had realized that the curved path followed by a missile or projectile is a parabola. He had arrived at his conclusion by realizing that a body undergoing ballistic motion executes, quite independently, the motion of a freely falling body in the vertical direction and inertial motion in the horizontal direction. These considerations, and terms such as ballistic and projectile, apply to a body that, once launched, is acted upon by no force other than Earth’s gravity.

Projectile motion may be thought of as an example of motion in space—that is to say, of three-dimensional motion rather than motion along a line, or one-dimensional motion. In a suitably defined system of Cartesian coordinates, the position of the projectile at any instant may be specified by giving the values of its three coordinates, x(t), y(t), and z(t). By generally accepted convention, z(t) is used to describe the vertical direction. To a very good approximation, the motion is confined to a single vertical plane, so that for any single projectile it is possible to choose a coordinate system such that the motion is two-dimensional [say, x(t) and z(t)] rather than three-dimensional [x(t), y(t), and z(t)]. It is assumed throughout this section that the range of the motion is sufficiently limited that the curvature of Earth’s surface may be ignored.

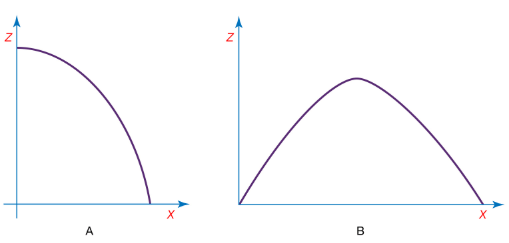

Consider a body whose vertical motion obeys equation (4), Galileo’s law of falling bodies, which states z = z0 − 1/2gt2, while, at the same time, moving horizontally at a constant speed vx in accordance with Galileo’s law of inertia. The body’s horizontal motion is thus described by x(t) = vxt, which may be written in the form t = x/vx. Using this result to eliminate t from equation gives z = z0 − 1/2g(1/vx)2x2. This latter is the equation of the trajectory of a projectile in the z–x plane, fired horizontally from an initial height z0. It has the general form

z = a+bx2 (21)

where a and b are constants. Equation (21) may be recognized to describe a parabola (Figure 5A), just as Galileo claimed. The parabolic shape of the trajectory is preserved even if the motion has an initial component of velocity in the vertical direction (Figure 5B).

z = a+bx2 (21)

Energy is conserved in projectile motion. The potential energy U(z) of the projectile is given by U(z) = mgz. The kinetic energy K is given by K = 1/2mv2, where v2 is equal to the sum of the squares of the vertical and horizontal components of velocity, or v2 = v2x + v2z.

In all of this discussion, the effects of air resistance (to say nothing of wind and other more complicated phenomena) have been neglected. These effects are seldom actually negligible. They are most nearly so for bodies that are heavy and slow-moving. All of this discussion, therefore, is of great value for understanding the underlying principles of projectile motion but of little utility for predicting the actual trajectory of, say, a cannonball once fired or even a well-hit baseball.

Motion of a pendulum:

According to legend, Galileo discovered the principle of the pendulum while attending mass at the Duomo (cathedral) located in the Piazza del Duomo of Pisa, Italy. A lamp hung from the ceiling by a cable and, having just been lit, was swaying back and forth. Galileo realized that each complete cycle of the lamp took the same amount of time, compared to his own pulse, even though the amplitude of each swing was smaller than the last. As has already been shown, this property is common to all harmonic oscillators, and, indeed, Galileo’s discovery led directly to the invention of the first accurate mechanical clocks. Galileo was also able to show that the period of oscillation of a simple pendulum is proportional to the square root of its length and does not depend on its mass.

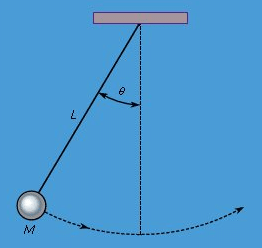

A simple pendulum is sketched in Figure. A bob of mass M is suspended by a massless cable or bar of length L from a point about which it pivots freely. The angle between the cable and the vertical is called θ. The force of gravity acting on the mass M, always equal to −Mg in the vertical direction, is a vector that may be resolved into two components, one that acts ineffectually along the cable and another, perpendicular to the cable, that tends to restore the bob to its equilibrium position directly below the point of suspension. This latter component is given by

A simple pendulum.

F = -Mg sinθ

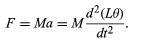

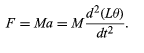

The bob is constrained by the cable to swing through an arc that is actually a segment of a circle of radius L. If the cable is displaced through an angle θ, the bob moves a distance Lθ along its arc (θ must be expressed in radians for this form to be correct). Thus, Newton’s second law may be written

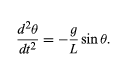

Equating equation to equation, one sees immediately that the mass M will drop out of the resulting equation. The simple pendulum is an example of a falling body, and its dynamics do not depend on its mass for exactly the same reason that the acceleration of a falling body does not depend on its mass: both the force of gravity and the inertia of the body are proportional to the same mass, and the effects cancel one another. The equation that results (after extracting the constant L from the derivative and dividing both sides by L) is

F = -Mg sinθ

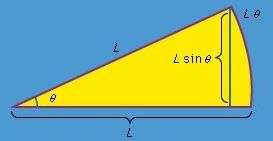

If the angle θ is sufficiently small, equation may be rewritten in a form that is both more familiar and more amenable to solution. Figure shows a segment of a circle of radius L. A radius vector at angle θ, as shown, locates a point on the circle displaced a distance Lθ along the arc. It is clear from the geometry that L sin θ and Lθ are very nearly equal for small θ. It follows then that sin θ and θ are also very nearly equal for small θ. Thus, if the analysis is restricted to small angles, then sin θ may be replaced by θ in equation to obtain

Equation should be compared with equation: d2x/dt2 = −(k/m)x. In the first case, the dynamic variable (meaning the quantity that changes with time) is θ, in the second case it is x. In both cases, the second derivative of the dynamic variable with respect to time is equal to the variable itself multiplied by a negative constant. The equations are therefore mathematically identical and have the same solution—i.e., equation, or θ = A cos ωt. In the case of the pendulum, the frequency of the oscillations is given by the constant in equation, or ω2 = g/L. The period of oscillation, T = 2π/ω, is therefore

Just as Galileo concluded, the period is independent of the mass and proportional to the square root of the length.

As with most problems in physics, this discussion of the pendulum has involved a number of simplifications and approximations. Most obviously, sin θ was replaced by θ to obtain equation. This approximation is surprisingly accurate. For example, at a not-very-small angle of 17.2°, corresponding to 0.300 radian, sin θ is equal to 0.296, an error of less than 2 percent. For smaller angles, of course, the error is appreciably smaller.

The problem was also treated as if all the mass of the pendulum were concentrated at a point at the end of the cable. This approximation assumes that the mass of the bob at the end of the cable is much larger than that of the cable and that the physical size of the bob is small compared with the length of the cable. When these approximations are not sufficient, one must take into account the way in which mass is distributed in the cable and bob. This is called the physical pendulum, as opposed to the idealized model of the simple pendulum. Significantly, the period of a physical pendulum does not depend on its total mass either.

The effects of friction, air resistance, and the like have also been ignored. These dissipative forces have the same effects on the pendulum as they do on any other kind of harmonic oscillator, as discussed above. They cause the amplitude of a freely swinging pendulum to grow smaller on successive swings. Conversely, in order to keep a pendulum clock going, a mechanism is needed to restore the energy lost to dissipative forces.

Circular motion:

Consider a particle moving along the perimeter of a circle at a uniform rate, such that it makes one complete revolution every hour. To describe the motion mathematically, a vector is constructed from the centre of the circle to the particle. The vector then makes one complete revolution every hour. In other words, the vector behaves exactly like the large hand on a wristwatch, an arrow of fixed length that makes one complete revolution every hour. The motion of the point of the vector is an example of uniform circular motion, and the period T of the motion is equal to one hour (T = 1 h). The arrow sweeps out an angle of 2π radians (one complete circle) per hour. This rate is called the angular frequency and is written ω = 2π h−1. Quite generally, for uniform circular motion at any rate,

These definitions and relations are the same as they are for harmonic motion, discussed above.

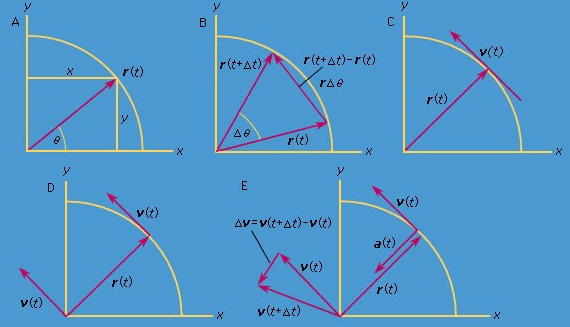

Consider a coordinate system, as shown in Figure, with the circle centred at the origin. At any instant of time, the position of the particle may be specified by giving the radius r of the circle and the angle θ between the position vector and the x-axis. Although r is constant, θ increases uniformly with time t, such that θ = ωt, or dθ/dt = ω, where ω is the angular frequency in equation. Contrary to the case of the wristwatch, however, ω is positive by convention when the rotation is in the counterclockwise sense. The vector r has x and y components given by

x = r cosθ = r cos ωt

y = r sinθ = r sin ωt

One meaning of equations is that, when a particle undergoes uniform circular motion, its x and y components each undergo simple harmonic motion. They are, however, not in phase with one another: at the instant when x has its maximum amplitude (say, at θ = 0), y has zero amplitude, and vice versa.

x = r cosθ = r cos ωt

y = r sinθ = r sin ωt

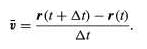

In a short time, Δt, the particle moves rΔθ along the circumference of the circle, as shown in Figure. The average speed of the particle is thus given by

The average velocity of the particle is a vector given by

This operation of vector subtraction is indicated in Figure. It yields a vector that is nearly perpendicular to r(t) and r(t + Δt). Indeed, the instantaneous velocity, found by allowing Δt to shrink to zero, is a vector v that is perpendicular to r at every instant and whose magnitude is

The relationship between r and v is shown in Figure. It means that the particle’s instantaneous velocity is always tangent to the circle.

Notice that, just as the position vector r may be described in terms of the components x and y given by equations, the velocity vector v may be described in terms of its projections on the x and y axes, given by

Imagine a new coordinate system, in which a vector of length ωr extends from the origin and points at all times in the same direction as v. This construction is shown in Figure. Each time the particle sweeps out a complete circle, this vector also sweeps out a complete circle. In fact, its point is executing uniform circular motion at the same angular frequency as the particle itself. Because vectors have magnitude and direction, but not position in space, the vector that has been constructed is the velocity v. The velocity of the particle is itself undergoing uniform circular motion at angular frequency ω.

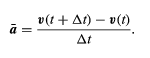

Although the speed of the particle is constant, the particle is nevertheless accelerated, because its velocity is constantly changing direction. The acceleration a is given by

a = dv/dt

Since v is a vector of length rω undergoing uniform circular motion, equations and may be repeated, as illustrated in Figure, giving

Thus, one may conclude that the instantaneous acceleration is always perpendicular to v and its magnitude is

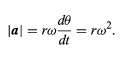

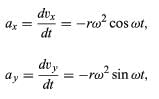

Since v is perpendicular to r, and a is perpendicular to v, the vector a is rotated 180° with respect to r. In other words, the acceleration is parallel to r but in the opposite direction. The same conclusion may be reached by realizing that a has x and y components given by

similar to equations and. When equations and are compared with equations and for x and y, it is clear that the components of a are just those of r multiplied by −ω2, so that a = −ω2 r. This acceleration is called the centripetal acceleration, meaning that it is inward, pointing along the radius vector toward the centre of the circle. It is sometimes useful to express the centripetal acceleration in terms of the speed v. Using v = ωr, one can write

|

217 videos|156 docs|94 tests

|

FAQs on Motion Of A Particle In Two Or More Dimensions - Basic Physics for IIT JAM

| 1. What is motion of a particle in two or more dimensions in physics? |  |

| 2. How is the motion of a particle in two or more dimensions different from one-dimensional motion? |  |

| 3. What are the components of motion in two or more dimensions? |  |

| 4. How is the trajectory of a particle determined in two or more dimensions? |  |

| 5. What are some real-life examples of motion in two or more dimensions? |  |