The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 3rd Sept, 2020 | Additional Study Material for UPSC PDF Download

1. GRIM SOVEREIGN TANGLE: ON GST COMPENSATION STANDOFF-

GS 3- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment

Context

Three years after India’s new indirect tax regime was introduced with a slogan of ‘One Nation, One Tax’, it faces an existential crisis.

Patchy Structure

(i) Despite its patchy(poor) structure with too many rates, complex compliance requirements and multiple mid-course changes, the implementation of the GST, had begun to almost serve as an exemplar(model) of co-operative federalism.

(ii) All of those gains have quickly unravelled(fell apart) as the slowdown in the economy, exacerbated(worsened) by the COVID-19 lockdowns, has thrown all revenue calculations to the wind.

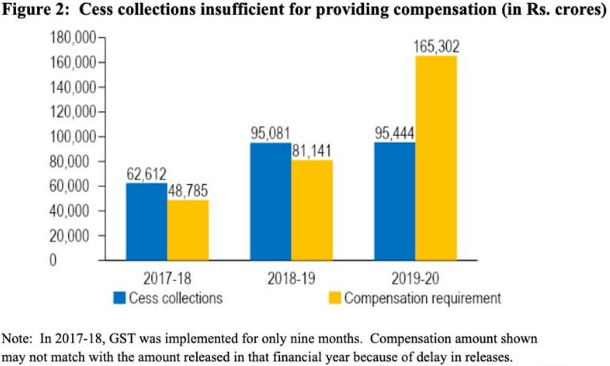

(iii) The Centre is obliged to pay to the States, for a period of five years, compensation for revenue shortfalls in return for their having ceded(given up) the power to levy the multiple taxes that were subsumed into the GST.

(iv) Last week, Finance Minister asserted, at what may have been the most tenuous GST Council meeting so far, that the Centre will not be able to meet the compensation shortfall.

(v) With GST collections sharply undershooting all targets this year, the Centre estimates compensation payable for the full year at ₹3-lakh crore.

(vi) But just ₹65,000 crore is expected in the cess(tax on tax) kitty used to pay out the compensation.

Rejected Options

(i) In July, the Centre paid out the last instalment of compensation for the last fiscal and is, so far, yet to pay anything for this year.

(ii) States have now been given two options, both requiring them to borrow from the market.

(iii) The Centre contends that only ₹97,000 crore of the revenue shortfall is from implementation of the GST, while ₹1.38-lakh crore is due to extraordinary circumstances posed by an ‘Act of God’ (the pandemic).

(iv) States can either borrow ₹97,000 crore, without having it added to their debt and with the principal and interest paid out from future cess collections, or they can borrow the entire ₹2.35-lakh crore shortfall, but will have to provide for interest payments themselves.

(v) The Finance Ministry has argued that higher borrowing by the Centre will push up interest rates and dent India’s fiscal parameters.

(vi) At best, this is specious — total government debt, including States’, is what rating agencies look at.

(vii) Several States have rejected both options and some, including Tamil Nadu, have urged the Centre to rethink in view of their essential and urgent spending needs to curb the pandemic and spur growth.

(viii) It is up to the Centre to resolve this impasse(difficult problem) in a way that future GST reforms do not fall victim to the trust deficit.

(ix) For now, the only certainty is that the compensation cess levied on demerit goods will stay on beyond 2022, and may even be raised, affecting several businesses, including the jobs-intensive auto sector.

Conclusion

GST reforms should not fall victim to the trust deficit from the compensation standoff.

2. DISSENT AND DETENTION: ON DR. KAFEEL KHAN-

GS 2- Important aspects of governance, transparency and accountability

Context

If ever any evidence was needed that Dr. Kafeel Khan, a government doctor from Gorakhpur, has been a victim of state persecution(harassment), the Allahabad High Court has provided that.

Malefic Manner

(i) Its 42-page order has laid bare(exposed) the malefic(wrong) manner in which the doctor was detained under the National Security Act (NSA) on February 13, 2020, shortly after he was granted bail in an earlier case.

(ii) Dr. Khan, suspended in 2017 after a severe shortage of oxygen cylinders took a deadly toll among children, was arrested on January 29, 2020, for an address to students of Aligarh Muslim University last December.

(iii) His speech, which contained scathing(severe) criticism of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, and its discriminatory nature, was deemed inflammatory weeks after he had made it.

(iv) The High Court has now found that far from inciting Muslims, the speech, taken in its entirety, does not disclose any effort to promote hatred or violence; and nowhere does it threaten peace in Aligarh.

(v) The DM, Aligarh, the court says, used selective reading of some phrases and ignored its true intent while passing the detention order.

(vi) No reasonable man, it says, would have come to the conclusion about the speech that the DM did.

(vii) The grounds for detention under NSA provided nothing that indicated any attempt by Dr. Khan to disturb peace and tranquillity(calmness) between the speech in December and his detention in February.

(viii) The inevitable inference is that the NSA was invoked(used) only to avoid releasing him following the Chief Judicial Magistrate court’s order granting him bail.

(ix) The process to invoke the NSA itself began only after the bail order, the Bench comprising Chief Justice Govind Mathur and Saumitra Dayal Singh noted.

Erosion Of Democratic Credentials

(i) The use of stringent(strict) national security laws against political dissenters, in the absence of any appeal to violence, is something to be condemned in all cases.

(ii) However, there is something perverse(ill) about the resort(usage) to preventive detention just to frustrate bail orders. In particular, the authorities have shown excessive zeal in dealing with Dr. Khan.

(iii) In 2017, he was arrested on charges of negligence and corruption even though circumstances indicated his strenuous efforts to ensure continuous oxygen supply.

(iv) He spent months in prison before an inquiry absolved(let him free) him of the charges of negligence and corruption, but was found to have been engaging in private practice.

(v) The paediatrician’s suspension is yet to be revoked(cancelled). Even though the verdict gives him relief, it comes after he spent seven months in jail. And his case will some day go to trial.

(vi) The case of Dr. Khan is poor advertisement for India’s democratic credentials. It brings to light its propensity(inclination) to criminalise dissent, single out individuals for persecution and display a general disregard for basic rights.

Conclusion

Allahabad HC order quashing(ending) Dr. Kafeel Khan’s detention exposes state persecution.

3. A GUIDE TO FLATTENING THE CURVE OF ECONOMIC CHAOS-

GS 3- Indian Economy and issues relating to planning, mobilization of resources, growth, development and employment

Context

(i) Now it is official: India has managed to become the global leader in the number of new daily cases of COVID-19 and the worst performing of all major economies during the pandemic so far.

(ii) How did we manage this double feat?

Data On The Decline

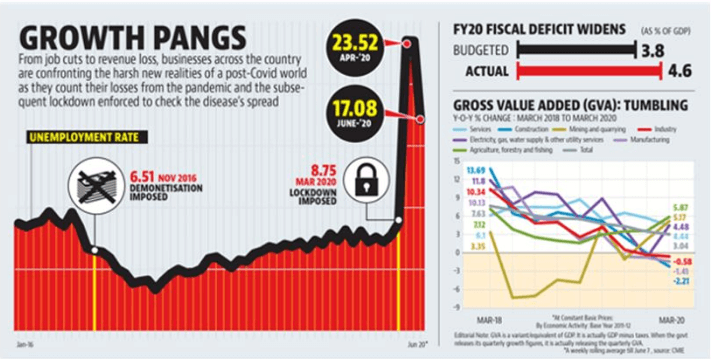

(i) The estimated 24% GDP contraction in April-June 2020 compared to the previous year is the worst performance among G20 economies, and even compared to other South Asian countries.

(ii) But these numbers are likely underestimates because they are based on information from the formal or organised sector, extrapolated to informal unorganised activities. The actual decline is probably worse.

(iii) Physical indicators such as the index of industrial production (covering registered manufacturing) declined by more than 20%, but ground reports indicate that unorganised manufacturing declined by much more.

(iv) Many micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in manufacturing and services are still closed or functioning at a small fraction of their capacity.

(v) Wage incomes are falling more sharply than GDP because of the combination of employment declines and falling wage rates.

(vi) There is other bad news in the GDP data: every sector other than agriculture declined sharply, especially the more employment-intensive sectors.

(vii) The good rabi harvest and very good monsoon provided some respite in agriculture, but with incomes down, farm prices are unlikely to revive and ensure sufficient returns for cultivators over the year.

(viii) Government consumption expenditure increased by about 16% over the same period in the previous year, but since total investment fell drastically (by around half), it is likely that public investment also fell.

(ix) And gross value added in public administration, defence and other services fell by more than 10%.

(x) Around 90% of this is salaries. Central government salaries have not fallen, so the squeeze must have fallen on State governments: many of them have probably frozen or delayed salary payments.

Grave Distress

(i) Meanwhile, the pandemic continues apparently unabated: all talk of “flattening the curve” (as wishful as the “green shoots” in the economy that official spokespersons keep seeing) has vanished, replaced by the completely meaningless indicator of recovery rates which are bound to improve with more cases.

(ii) The brutal national lockdown generated economic collapse even before the disease had spread much.

(iii) Instead of testing, tracing, isolating and treating — which is costly but is still the only effective way to deal with this disease — the central government shut everything down across the country without warning.

(iv) Then it provided no compensation and almost no social protection to those (around 80% of workers) who lost livelihood.

(v) Migrant workers were forced to return in terrible conditions to their homes, where they have unwittingly spread the disease in rural areas with poor health facilities.

(vi) Working people have been impoverished(poor) and debilitated(weak) by lack of nutrition because they have been less able to afford food.

(vii) Now they are being told to go back to work (mostly at lower wages) even as the risk of disease has grown exponentially.

(viii) What is more terrifying is that this is still just the beginning: there is little reason to believe that this awful trajectory will be halted unless there is a major change in government strategy on both health and the economy.

(ix) The downturn is definitely extending into the current quarter, and probably the rest of the year, so we are staring at the biggest economic crisis in independent India.

Blow Against States

(i) Lack of demand is a crucial reason for this. Both consumption and investment were declining well before the pandemic struck.

(ii) Thereafter, despite the enormity of the economic collapse, the government’s relief responses have been pathetically small, barely touching the hundreds of millions of people affected and with little impact on aggregate demand.

(iii) The halting steps taken on increasing liquidity have been effectively useless: bank credit has declined overall, and (other than favoured large companies) all types of borrowers have received less bank credit.

(iv) The most disgraceful treatment has been of State governments. Despite the centralising imposition of the national Disaster Management Act, there was almost no coordination.

(v) State governments have been forced to do all the heavy lifting of dealing with the health crisis and the economic effects of the pandemic on their own, even as the Centre has denied them resources to do this effectively.

(vi) The Centre is even denying the States their legal dues of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) compensation cess.

(vii) This reneging(backing out) of a contractual promise could spell the end of what has been a poorly conceived, badly planned and worse implemented GST.

(viii) The consequences of this stinginess(miserly) will be felt directly by citizens.

(ix) Most State governments front-ended their expenditures for the entire year to deal with the crisis and are now running out of money.

(x) Unlike the Centre, they face hard budget constraints and gave up their revenue-raising powers to the GST.

(xi) They are now being told to borrow money (that the Centre owes them!) when it is uncertain how they will repay.

(xii) This is going to affect their spending for the rest of the year and people will feel the results in reduced basic services.

Solution

(i) The central government must immediately provide a large fiscal package (with actual money made available, not empty promises) including the following:

(a) pay the State governments their pending GST compensation dues and provide more resources in addition to deal with the pandemic and its effects;

(b) universalise the Public Distribution System (PDS) and provide free foodgrain (10 kg per household per month) for at least the next six months to anyone who needs it;

(c) provide ₹7,000 per family for three months as compensation for the incomes lost during the draconian lockdown;

(d) double the number of days of employment per household under the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act to 200 per year (for this year at least) and start an urban employment guarantee programme;

(e) extend the debt moratorium and convert into a standstill (without requiring interest payments for that period) and make sure that fresh credit reaches MSMEs and farmers who are being deprived of it;

(f) provide much more dedicated resources for health: for all the pandemic-required spending, and to deal with other health concerns that have been ignored or postponed for the past five months.

Conclusion

(i) This will cost money, for sure; but not doing this will be even more costly for the economy and the people.

(ii) Not spending now will push the economy into a deeper hole, reducing incomes and, therefore, also taxes, and creating a bigger fiscal deficit even with lower spending.

(iii) For now, these increased expenditures can be paid for by the Centre borrowing from the Reserve Bank of India (monetising the deficit, as governments across the world have been doing).

(iv) This will not be inflationary as long as essential supplies are maintained, because demand is currently so low.

(v) Eventually, wealth taxes and taxes on multinational corporations (especially digital giants that manage to avoid taxes) must be thought of.

(vi) Bold thinking and urgent action are the only way out.

|

21 videos|562 docs|160 tests

|

FAQs on The Hindu Editorial Analysis- 3rd Sept, 2020 - Additional Study Material for UPSC

| 1. What is the significance of the UPSC exam? |  |

| 2. What is the format of the UPSC exam? |  |

| 3. What are the key topics covered in the UPSC exam syllabus? |  |

| 4. How can one prepare effectively for the UPSC exam? |  |

| 5. What are some common challenges faced by UPSC aspirants? |  |