UPSC Exam > UPSC Notes > UPSC Mains: World History > First World War (1914)- 2

First World War (1914)- 2 | UPSC Mains: World History PDF Download

The Eastern and other fronts, 1914

The war in the east, 1914

- On the Eastern Front, greater distances and quite considerable differences between the equipment and quality of the opposing armies ensured a fluidity of the front that was lacking in the west. Trench lines might form, but to break them was not difficult, particularly for the German army, and then mobile operations of the old style could be undertaken.

- Urged by the French to take offensive action against the Germans, the Russian commander in chief, Grand Duke Nicholas, took it loyally but prematurely, before the cumbrous Russian war machine was ready, by launching a pincer movement against East Prussia. Under the higher control of General Ya.G. Zhilinsky, two armies, the 1st, or Vilna, Army under P.K. Rennenkampf and the 2nd, or Warsaw, Army under A.V. Samsonov, were to converge, with a two-to-one superiority in numbers, on the German 8th Army in East Prussia from the east and the south, respectively. Rennenkampf’s left flank would be separated by 50 miles from Samsonov’s right flank.

- Max von Prittwitz und Gaffron, commander of the 8th Army, with his headquarters at Neidenburg (Nidzica), had seven divisions and one cavalry division on his eastern front but only the three divisions of Friedrich von Scholtz’s XX Corps on his southern. He was therefore dismayed to learn, on August 20, when the bulk of his forces had been repulsed at Gumbinnen (August 19–20) by Rennenkampf’s attack from the east, that Samsonov’s 13 divisions had crossed the southern frontier of East Prussia and were thus threatening his rear.

- He initially considered a general retreat, but when his staff objected to this, he approved their counterproposal of an attack on Samsonov’s left flank, for which purpose three divisions were to be switched in haste by rail from the Gumbinnen front to reinforce Scholtz (the rest of the Gumbinnen troops could make their retreat by road). The principal exponent of this counterproposal was Lieutenant Colonel Max Hoffmann. Prittwitz, having moved his headquarters northward to Mühlhausen (Młynary), was surprised on August 22 by a telegram announcing that General Paul von Hindenburg, with Ludendorff as his chief of staff, was coming to supersede him in command. Arriving the next day, Ludendorff readily confirmed Hoffmann’s dispositions for the blow at Samsonov’s left.

- Meanwhile, Zhilinsky was not only giving Rennenkampf time to reorganize after Gumbinnen but even instructing him to invest Königsberg instead of pressing on to the west. When the Germans on August 25 learned from an intercepted Russian wireless message (the Russians habitually transmitted combat directives “in clear,” not in code) that Rennenkampf was in no hurry to advance, Ludendorff saw a new opportunity. Developing the plan put forward by Hoffmann, Ludendorff concentrated about six divisions against Samsonov’s left wing.

- This force, inferior in strength, could not have been decisive, but Ludendorff then took the calculated risk of withdrawing the rest of the German troops, except for a cavalry screen, from their confrontation with Rennenkampf and rushing them southwestward against Samsonov’s right wing. Thus, August von Mackensen’s XVII Corps was taken from near Gumbinnen and moved southward to duplicate the planned German attack on Samsonov’s left with an attack on his right, thus completely enveloping the Russian 2nd Army. This daring move was made possible by the notable absence of communication between the two Russian field commanders, whom Hoffmann knew to personally dislike each other.

- Under the Germans’ converging blows Samsonov’s flanks were crushed and his centre surrounded during August 26–31. The outcome of this military masterpiece, called the Battle of Tannenberg, was the destruction or capture of almost the whole of Samsonov’s army. The history of imperial Russia’s unfortunate participation in World War I is epitomized in the ignominious outcome of the Battle of Tannenberg.

- The progress of the battle was as follows. Samsonov, his forces spread out along a front 60 miles long, was gradually pushing Scholtz back toward the Allenstein–Osterode (Olsztyn–Ostróda) line when, on August 26, Ludendorff ordered General Hermann von François, with the I Corps on Scholtz’s right, to attack Samsonov’s left wing near Usdau (Uzdowo).

- There, on August 27, German artillery bombardments threw the hungry and weary Russians into precipitate flight. François started to pursue them toward Neidenburg, in the rear of the Russian centre, and then made a momentary diversion southward, to check a Russian counterattack from Soldau (Działdowo). Two of the Russian 2nd Army’s six army corps managed to escape southeastward at this point, and François then resumed his pursuit to the east. By nightfall on August 29 his troops were in control of the road leading from Neidenburg eastward to Willenberg (Wielbark). The Russian centre, amounting to three army corps, was now caught in the maze of forest between Allenstein and the frontier of Russian Poland.

- It had no line of retreat, was surrounded by the Germans, and soon dissolved into mobs of hungry and exhausted men who beat feebly against the encircling German ring and then allowed themselves to be taken prisoner by the thousands. Samsonov shot himself in despair on August 29. By the end of August the Germans had taken 92,000 prisoners and annihilated half of the Russian 2nd Army. Ludendorff’s bold recall of the last German forces facing Rennenkampf’s army was wholly justified in the event, since Rennenkampf remained utterly passive while Samsonov’s army was surrounded.

- Having received two fresh army corps (seven divisions) from the Western Front, the Germans now turned on the slowly advancing 1st Army under Rennenkampf. The latter was attacked on a line extending from east of Königsberg to the southern end of the chain of the Masurian Lakes during September 1–15 and was driven from East Prussia. As a result of these East Prussian battles Russia had lost about 250,000 men and, what could be afforded still less, much war matériel. But the invasion of East Prussia had at least helped to make possible the French comeback on the Marne by causing the dispatch of two German army corps from the Western Front.

- Having ended the Russian threat to East Prussia, the Germans could afford to switch the bulk of their forces from that area to the Częstochowa–Kraków front in southwestern Poland, where the Austrian offensive, launched on August 20, had been rolled back by Russian counterattacks. A new plan for simultaneous thrusts by the Germans toward Warsaw and by the Austrians toward Przemyśl was brought to nothing by the end of October, as the Russians could now mount counterattacks in overwhelming strength, their mobilization being at last nearly completed.

- The Russians then mounted a powerful effort to invade Prussian Silesia with a huge phalanx of seven armies. Allied hopes rose high as the much-heralded “Russian steamroller” (as the huge Russian army was called) began its ponderous advance. The Russian armies were advancing toward Silesia when Hindenburg and Ludendorff, in November, exploited the superiority of the German railway network: when the retreating German forces had crossed the frontier back into Prussian Silesia, they were promptly moved northward into Prussian Poland and thence sent southeastward to drive a wedge between the two armies of the Russian right flank.

- The massive Russian operation against Silesia was disorganized, and within a week four new German army corps had arrived from the Western Front. Ludendorff was able to use them to press the Russians back by mid-December to the Bzura–Rawka (rivers) line in front of Warsaw, and the depletion of their munition supplies compelled the Russians to also fall back in Galicia to trench lines along the Nida and Dunajec rivers.

The Serbian campaign, 1914

- The first Austrian invasion of Serbia was launched with numerical inferiority (part of one of the armies originally destined for the Balkan front having been diverted to the Eastern Front on August 18), and the able Serbian commander, Radomir Putnik, brought the invasion to an early end by his victories on the Cer Mountain (August 15–20) and at Šabac (August 21–24). In early September, however, Putnik’s subsequent northward offensive on the Sava River, in the north, had to be broken off when the Austrians began a second offensive, against the Serbs’ western front on the Drina River.

- After some weeks of deadlock, the Austrians began a third offensive, which had some success in the Battle of the Kolubara, and forced the Serbs to evacuate Belgrade on November 30, but by December 15 a Serbian counterattack had retaken Belgrade and forced the Austrians to retreat. Mud and exhaustion kept the Serbs from turning the Austrian retreat into a rout, but the victory sufficed to allow Serbia a long spell of freedom from further Austrian advances.

The Turkish entry

- The entry of Turkey (or the Ottoman Empire, as it was then called) into the war as a German ally was the one great success of German wartime diplomacy. Since 1909 Turkey had been under the control of the Young Turks, over whom Germany had skillfully gained a dominating influence. German military instructors permeated the Turkish army, and Enver Paşa, the leader of the Young Turks, saw alliance with Germany as the best way of serving Turkey’s interests, in particular for protection against the Russian threat to the straits. He therefore persuaded the grand vizier, Said Halim Paşa, to make a secret treaty (negotiated late in July, signed on August 2) pledging Turkey to the German side if Germany should have to take Austria-Hungary’s side against Russia.

- The unforeseen entry of Great Britain into the war against Germany alarmed the Turks, but the timely arrival of two German warships, the Goeben and the Breslau, in the Dardanelles on August 10 turned the scales in favour of Enver’s policy. The ships were ostensibly sold to Turkey, but they retained their German crews. The Turks began detaining British ships, and more anti-British provocations followed, both in the straits and on the Egyptian frontier.

- Finally the Goeben led the Turkish fleet across the Black Sea to bombard Odessa and other Russian ports (October 29–30). Russia declared war against Turkey on November 1; and the western Allies, after an ineffective bombardment of the outer forts of the Dardanelles on November 3, declared war likewise on November 5. A British force from India occupied Basra, on the Persian Gulf, on November 21. In the winter of 1914–15 Turkish offensives in the Caucasus and in the Sinai Desert, albeit abortive, served German strategy well by tying Russian and British forces down in those peripheral areas.

The war at sea, 1914–15

- In August 1914 Great Britain, with 29 capital ships ready and 13 under construction, and Germany, with 18 and nine, were the two great rival sea powers. Neither of them at first wanted a direct confrontation: the British were chiefly concerned with the protection of their trade routes; the Germans hoped that mines and submarine attacks would gradually destroy Great Britain’s numerical superiority, so that confrontation could eventually take place on equal terms.

World War I; Royal Navy

World War I; Royal Navy

- The first significant encounter between the two navies was that of the Helgoland Bight, on August 28, 1914, when a British force under Admiral Sir David Beatty, having entered German home waters, sank or damaged several German light cruisers and killed or captured 1,000 men at a cost of one British ship damaged and 35 deaths. For the following months the Germans in European or British waters confined themselves to submarine warfare—not without some notable successes: on September 22 a single German submarine, or U-boat, sank three British cruisers within an hour; on October 7 a U-boat made its way into the anchorage of Loch Ewe, on the west coast of Scotland; on October 15 the British cruiser Hawke was torpedoed; and on October 27 the British battleship Audacious was sunk by a mine.

- On December 15 battle cruisers of the German High Seas Fleet set off on a sortie across the North Sea, under the command of Admiral Franz von Hipper: they bombarded several British towns and then made their way home safely. Hipper’s next sortie, however, was intercepted on its way out: on January 24, 1915, in the Battle of the Dogger Bank, the German cruiser Blücher was sunk and two other cruisers damaged before the Germans could make their escape.

- Abroad on the high seas, the Germans’ most powerful surface force was the East Asiatic squadron of fast cruisers, including the Scharnhorst, the Gneisenau, and the Nürnberg, under Admiral Graf Maximilian von Spee. For four months this fleet ranged almost unhindered over the Pacific Ocean, while the Emden, having joined the squadron in August 1914, was detached for service in the Indian Ocean. The Germans could thus threaten not only merchant shipping on the British trade routes but also troopships on their way to Europe or the Middle East from India, New Zealand, or Australia.

- The Emden sank merchant ships in the Bay of Bengal, bombarded Madras (September 22; now Chennai, India), haunted the approaches to Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and had destroyed 15 Allied ships in all before it was caught and sunk off the Cocos Islands on November 9 by the Australian cruiser Sydney.

- Meanwhile, Admiral von Spee’s main squadron since August had been threading a devious course in the Pacific from the Caroline Islands toward the Chilean coast and had been joined by two more cruisers, the Leipzig and the Dresden. On November 1, in the Battle of Coronel, it inflicted a sensational defeat on a British force, under Sir Christopher Cradock, which had sailed from the Atlantic to hunt it down: without losing a single ship, it sank Cradock’s two major cruisers, Cradock himself being killed. But the fortunes of the war on the high seas were reversed when, on December 8, the German squadron attacked the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands in the South Atlantic, probably unaware of the naval strength that the British, since Coronel, had been concentrating there under Admiral Sir Doveton Sturdee: two battle cruisers (the Invincible and Inflexible, each equipped with eight 12-inch guns) and six other cruisers.

- The German ships were suffering from wear and tear after their long cruise in the Pacific and were no match for the newer, faster British ships, which soon overtook them. The Scharnhorst, with Admiral von Spee aboard, was the first ship to be sunk, then the Gneisenau, followed by the Nürnberg and the Leipzig. The British ships, which had fought at long range so as to render useless the smaller guns of the Germans, sustained only 25 casualties in this engagement. When the German light cruiser Dresden was caught and sunk off the Juan Fernández Islands on March 14, 1915, commerce raiding by German surface ships on the high seas was at an end. It was just beginning by German submarines, however.

- The belligerent navies were employed as much in interfering with commerce as in fighting each other. Immediately after the outbreak of war, the British had instituted an economic blockade of Germany, with the aim of preventing all supplies reaching that country from the outside world. The two routes by which supplies could reach German ports were: (1) through the English Channel and the Strait of Dover and (2) around the north of Scotland.

- A minefield laid in the Strait of Dover with a narrow free lane made it fairly easy to intercept and search ships using the Channel. To the north of Scotland, however, there was an area of more than 200,000 square miles (520,000 square kilometres) to be patrolled, and the task was assigned to a squadron of armed merchant cruisers. During the early months of the war, only absolute contraband such as guns and ammunition was restricted, but the list was gradually extended to include almost all material that might be of use to the enemy.

- The prevention of the free passage of trading ships led to considerable difficulties among the neutral nations, particularly with the United States, whose trading interests were hampered by British policy. Nevertheless, the British blockade was extremely effective, and during 1915 the British patrols stopped and inspected more than 3,000 vessels, of which 743 were sent into port for examination. Outward-bound trade from Germany was brought to a complete standstill.

- The Germans similarly sought to attack Great Britain’s economy with a campaign against its supply lines of merchant shipping. In 1915, however, with their surface commerce raiders eliminated from the conflict, they were forced to rely entirely on the submarine.

- The Germans began their submarine campaign against commerce by sinking a British merchant steamship (Glitra), after evacuating the crew, on October 20, 1914. A number of other sinkings followed, and the Germans soon became convinced that the submarine would be able to bring the British to an early peace where the commerce raiders on the high seas had failed. On January 30, 1915, Germany carried the campaign a stage further by torpedoing three British steamers (Tokomaru, Ikaria, and Oriole) without warning. They next announced, on February 4, that from February 18 they would treat the waters around the British Isles as a war zone in which all Allied merchant ships were to be destroyed, and in which no ship, whether enemy or not, would be immune.

- Yet, whereas the Allied blockade was preventing almost all trade for Germany from reaching that nation’s ports, the German submarine campaign yielded less satisfactory results. During the first week of the campaign seven Allied or Allied-bound ships were sunk out of 11 attacked, but 1,370 others sailed without being harassed by the German submarines.

- In the whole of March 1915, during which 6,000 sailings were recorded, only 21 ships were sunk, and in April only 23 ships from a similar number. Apart from its lack of positive success, the U-boat arm was continuously harried by Great Britain’s extensive antisubmarine measures, which included nets, specially armed merchant ships, hydrophones for locating the noise of a submarine’s engines, and depth bombs for destroying it underwater.

- For the Germans, a worse result than any of the British countermeasures imposed on them was the long-term growth of hostility on the part of the neutral countries. Certainly the neutrals were far from happy with the British blockade, but the German declaration of the war zone and subsequent events turned them progressively away from their attitude of sympathy for Germany.

- The hardening of their outlook began in February 1915, when the Norwegian steamship Belridge, carrying oil from New Orleans to Amsterdam, was torpedoed and sunk in the English Channel. The Germans continued to sink neutral ships occasionally, and undecided countries soon began to adopt a hostile outlook toward this activity when the safety of their own shipping was threatened.

- Much more serious was an action that confirmed the inability of the German command to perceive that a minor tactical success could constitute a strategic blunder of the most extreme magnitude. This was the sinking by a German submarine on May 7, 1915, of the British liner Lusitania, which was on its way from New York to Liverpool: though the ship was in fact carrying 173 tons of ammunition, it had nearly 2,000 civilian passengers, and the 1,198 people who were drowned included 128 U.S. citizens.

- The loss of the liner and so many of its passengers, including the Americans, aroused a wave of indignation in the United States, and it was fully expected that a declaration of war might follow. But the U.S. government clung to its policy of neutrality and contented itself with sending several notes of protest to Germany. Despite this, the Germans persisted in their intention and, on August 17, sank the Arabic, which also had U.S. and other neutral passengers.

- Following a new U.S. protest, the Germans undertook to ensure the safety of passengers before sinking liners henceforth; but only after the torpedoing of yet another liner, the Hesperia, did Germany, on September 18, decide to suspend its submarine campaign in the English Channel and west of the British Isles, for fear of provoking the United States further. The German civilian statesmen had temporarily prevailed over the naval high command, which advocated “unrestricted” submarine warfare.

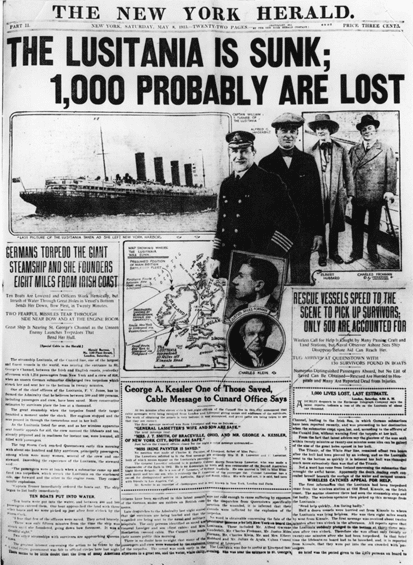

Sinking of the Lusitania

Sinking of the Lusitania

The New York Herald reporting the sinking of the Lusitania, a British ocean liner, by a German submarine on May 7, 1915.

The loss of the German colonies

- Germany’s overseas colonies, virtually without hope of reinforcement from Europe, defended themselves with varying degrees of success against Allied attack.

- Togoland was conquered by British forces from the Gold Coast (now Ghana) and by French forces from Dahomey (now Benin) in the first month of the war. In the Cameroons (German: Kamerun), invaded by Allied forces from the south, the east, and the northwest in August 1914 and attacked from the sea in the west, the Germans put up a more effective resistance, and the last German stronghold there, Mora, held out until February 18, 1916.

- Operations by South African forces in huge numerical superiority were launched against German South West Africa (Namibia) in September 1914 but were held up by the pro-German rebellion of certain South African officers who had fought against the British in the South African War of 1899–1902. The rebellion died out in February 1915, but the Germans in South West Africa nevertheless did not capitulate until July 9.

- In Jiaozhou (Kiaochow) Bay a small German enclave on the Chinese coast, the port of Qingdao (Tsingtao) was the object of Japanese attack from September 1914. With some help from British troops and from Allied warships, the Japanese captured it on November 7. In October, meanwhile, the Japanese had occupied the Marianas, the Caroline Islands, and the Marshalls in the North Pacific, these islands being defenseless since the departure of Admiral von Spee’s naval squadron.

- In the South Pacific, Western Samoa (now Samoa) fell without blood at the end of August 1914 to a New Zealand force supported by Australian, British, and French warships. In September an Australian invasion of Neu-Pommern (New Britain) won the surrender of the whole colony of German New Guinea within a few weeks.

- The story of German East Africa (comprising present-day Rwanda, Burundi, and continental Tanzania) was very different, thanks to the quality of the local askaris (European-trained African troops) and to the military genius of the German commander Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck. A landing of troops from India was repelled with ignominy by the Germans in November 1914.

- A massive invasion from the north, comprising British and colonial troops under the South African J.C. Smuts, was launched in February 1916, to be coordinated with a Belgian invasion from the west and with an independent British one from Nyasaland in the south, but, though Dar es Salaam fell to Smuts and Tabora to the Belgians in September, Lettow-Vorbeck maintained his small force in being. In November 1917 he began to move southward across Portuguese East Africa (Germany had declared war on Portugal in March 1916), and, after crossing back into German East Africa in September 1918, he turned southwestward to invade Northern Rhodesia in October. Having taken Kasama on November 9 (two days before the German armistice in Europe), he finally surrendered on November 25. With some 12,000 men at the outset, he eventually tied down 130,000 or more Allied troops.

The document First World War (1914)- 2 | UPSC Mains: World History is a part of the UPSC Course UPSC Mains: World History.

All you need of UPSC at this link: UPSC

|

50 videos|69 docs|30 tests

|

FAQs on First World War (1914)- 2 - UPSC Mains: World History

| 1. What were the major fronts during the First World War in 1914? |  |

Ans. The major fronts during the First World War in 1914 were the Eastern Front, Western Front, Italian Front, Balkan Front, and the Middle Eastern Front.

| 2. What was the significance of the Eastern Front during the First World War? |  |

Ans. The Eastern Front was a crucial theater of war during the First World War. It witnessed heavy fighting between the Central Powers (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Bulgaria) and the Allies (Russia, France, and the United Kingdom). The Eastern Front was characterized by massive troop movements, trench warfare, and major battles such as the Battle of Tannenberg and the Battle of the Masurian Lakes.

| 3. How did the Eastern Front impact the course of the First World War? |  |

Ans. The Eastern Front had a significant impact on the course of the First World War. The heavy casualties suffered by both sides on this front weakened their overall war efforts. The diversion of German forces to the Eastern Front also reduced their strength on the Western Front, allowing the Allies to launch successful offensives. Additionally, the Russian Revolution of 1917, partly influenced by the hardships faced on the Eastern Front, led to Russia's withdrawal from the war and a shift in the balance of power.

| 4. What challenges did soldiers face on the Eastern Front during the First World War? |  |

Ans. Soldiers on the Eastern Front faced numerous challenges during the First World War. Harsh weather conditions, particularly during the bitterly cold Russian winters, made survival difficult. Trench warfare, similar to that on the Western Front, exposed soldiers to constant danger and hardships. Supply lines were often stretched thin, leading to shortages of food, ammunition, and medical supplies. The vast size of the front and the large number of troops involved also made coordination and communication challenging.

| 5. How did the Eastern Front contribute to the political and territorial changes after the First World War? |  |

Ans. The Eastern Front played a significant role in shaping the political and territorial changes that followed the First World War. The defeat of the Central Powers on this front led to the disintegration of the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in 1918 resulted in significant territorial losses for Russia. The Eastern Front also set the stage for future conflicts and tensions, particularly between the newly independent states in Eastern Europe.

Related Searches