The USA before the Second World War- 1 | UPSC Mains: World History PDF Download

Summary Of Events

During the second half of the nineteenth century, the USA experienced remarkable social and economic changes.

- The Civil War (1861–5) between North and South brought the end of slavery in the USA and freedom for the former slaves. However, many whites, especially in the South, were reluctant to recognize black people (African Americans) as equals and did their best to deprive them of their new rights. This led to the beginning of the Civil Rights movement, although it had very little success until the second half of the twentieth century.

- Large numbers of immigrants began to arrive from Europe, and this continued into the twentieth century. Between 1860 and 1930 over 30 million people arrived in the USA from abroad.

- There was a vast and successful industrial revolution, mainly in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. The USA entered the twentieth century on a wave of business prosperity. By 1914 she had easily surpassed Britain and Germany, the leading industrial nations of Europe, in output of coal, iron and steel, and was clearly a rival economic force to be reckoned with.

- Although industrialists and financiers did well and made their fortunes, prosperity was not shared equally among the American people. Immigrants, blacks and women often had to put up with low wages and poor living and working conditions. This led to the formation of labour unions and the Socialist Party, which tried to improve the situation for the workers. However, big business was unsympathetic, and these organizations had very little success before the First World War (1914–18).

Although the Americans came late into the First World War (April 1917), they played an important part in the defeat of Germany and her allies; Democrat President Woodrow Wilson (1913–21) was a leading figure at the Versailles Conference, and the USA was now one of the world’s great powers. However, after the war the Americans decided not to play an active role in world affairs, a policy known as isolationism. It was a bitter disappointment for Wilson when the Senate rejected both the Versailles settlement and the League of Nations (1920).

After Wilson came three Republican presidents: Warren Harding (1921–3), who died in office; Calvin Coolidge (1923–9) and Herbert C. Hoover (1929–33). Until 1929 the country enjoyed a period of great prosperity, though not everybody shared in it. The boom ended suddenly with the Wall Street Crash (October 1929), which led to the Great Depression, or world economic crisis, only six months after the unfortunate Hoover’s inauguration. The effects on the USA were catastrophic: by 1933 almost 14 million people were out of work and Hoover’s efforts failed to make any impression on the crisis. Nobody was surprised when the Republicans lost the presidential election of November 1932.

The new Democrat president, Franklin D. Roosevelt, introduced policies known as the New Deal to try and put the country on the road to recovery. Though it was not entirely successful, the New Deal achieved enough, together with the circumstances of the Second World War, to keep Roosevelt in the White House (the official residence of the president in Washington) until his death in April 1945. He was the only president to be elected for a fourth term.

The American System of Government

The American Constitution (the set of rules by which the country is governed) was first drawn up in 1787. Since then, 26 extra points (Amendments) have been added; the last one, which lowered the voting age to 18, was added in 1971.

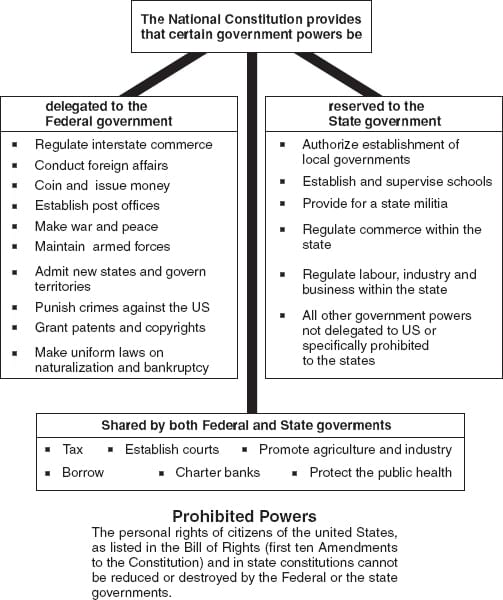

The USA has a federal system of government

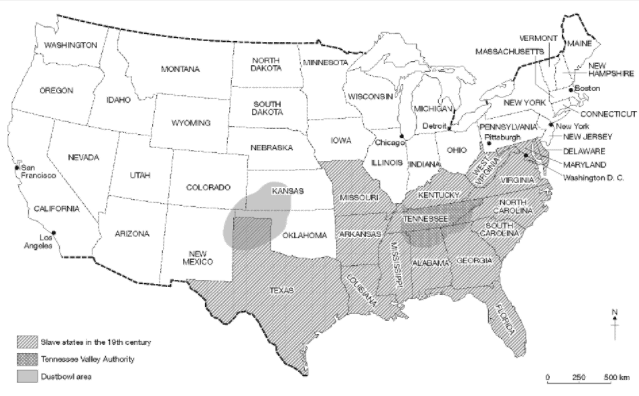

This is a system in which a country is divided up into a number of states. There were originally 13 states in the USA; by 1900 the number had grown to 45 as the frontier was extended westwards. Later, five more states were formed and added to the union; these were Oklahoma (1907), Arizona and New Mexico (1912), and Alaska and Hawaii (1959). Each of these states has its own state capital and government and they share power with the federal (central or national) government in the federal capital, Washington. shows how the power is shared out.

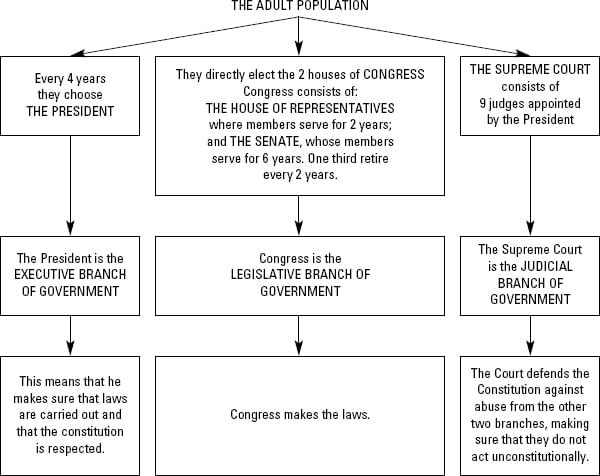

The federal government consists of three main parts:

Congress: known as the legislative part, which makes the laws;

President: known as the executive part; he carries out the laws;

Judiciary: the legal system, of which the most important part is the Supreme Court.

(a) Congress

- The federal parliament, known as Congress, meets in Washington and consists of two houses:

(i) the House of Representatives

(ii) the Senate

Members of both houses are elected by universal suffrage. The House of Representatives (usually referred to simply as ‘the House’) contains 435 members, elected for two years, who represent districts of roughly equal population. Senators are elected for six years, one third retiring every two years; there are two from each state, irrespective of the population of the state, making a total of 100. - The main job of Congress is to legislate (make the laws). All new laws have to be passed by a simple majority in both houses; treaties with foreign countries need a two-thirds vote in the Senate. If there is a disagreement between the two houses, a joint conference is held, which usually succeeds in producing a compromise proposal, which is then voted on by both houses. Congress can make laws about taxation, currency, postage, foreign trade and the army and navy. It also has the power to declare war. In 1917, for example, when Woodrow Wilson decided it was time for the USA to go to war with Germany, he had to ask Congress to declare war.

- There are two main parties represented in Congress:

Republicans

Democrats

The USA between the wars

How the federal government and the states divide powers in the USA

How the federal government and the states divide powers in the USA

Both parties contain people of widely differing views.

The Republicans have traditionally been a party which has a lot of support in the North, particularly among businessmen and industrialists. The more conservative of the two parties, its members believed in:

- keeping high tariffs (import duties) to protect American industry from foreign imports;

- a laissez-faire approach to government: they wanted to leave businessmen alone to run industry and the economy with as little interference from the government as possible. Republican Presidents Coolidge (1923–9) and Hoover (1929–33), for example, both favoured non-intervention and felt that it was not the government’s job to sort out economic and social problems.

The Democrats have drawn much of their support from the South, and from immigrants in the large cities of the North. They have been the more progressive of the two parties: Democrat presidents such as Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933–45), Harry S. Truman (1945–53) and John F. Kennedy (1961–3) wanted the government to take a more active role in dealing with social and economic problems.

However, the parties are not as united or as tightly organized as political parties in Britain, where all the MPs belonging to the government party are expected to support the government all the time. In the USA, party discipline is much weaker, and votes in Congress often cut across party lines. There are left- and right-wingers in both parties. Some right-wing Democrats voted against Roosevelt’s New Deal even though he was a Democrat, while some left-wing Republicans voted for it. But they did not change parties, and their party did not throw them out.

(b) The President

The President is elected for a four-year term. Each party chooses its candidate for the presidency and the election always takes place in November. The successful candidate (referred to as the ‘President elect’) is sworn in as President the following January. The powers of the President appear to be very wide: he (or she) is Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, controls the civil service, runs foreign affairs, makes treaties with foreign states, and appoints judges, ambassadors and the members of the cabinet. With the help of supporters among the Congressmen, the President can introduce laws into Congress and can veto laws passed by Congress if he or she does not approve of them.

(c) The Supreme Court

This consists of nine judges appointed by the President, with the approval of the Senate. Once a Supreme Court judge is appointed, he or she can remain in office for life, unless forced to resign through ill health or scandal. The court acts as adjudicator in disputes between President and Congress, between the federal and state governments, between states, and in any problems which arise from the constitution.

(d) The separation of powers

When the Founding Fathers of the USA (among whom were George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, Alexander Hamilton and James Madison) met in Philadelphia in 1787 to draw up the new Constitution, one of their main concerns was to make sure that none of the three parts of government – Congress, President and Supreme Court – became too powerful. They deliberately devised a system of ‘checks and balances’ in which the three branches of government work separately from each other. The President and his cabinet, for example, are not members of Congress, unlike the British prime minister and cabinet, who are all members of parliament. Each branch acts as a check on the power of the others. This means that the President is not as powerful as he might appear: since elections for the House are held every two years and a third of the Senate is elected every two years, a President’s party can lose its majority in one or both houses after he or she has been in office only two years.

The three separate branches of the US federal government

The three separate branches of the US federal government

Although the President can veto laws, Congress can over-rule this veto if it can raise a two-thirds majority in both houses. Nor can the President dissolve Congress; it is just a question of hoping that things will change for the better at the next set of elections. On the other hand, Congress cannot get rid of the President unless it can be shown that he or she has committed treason or some other serious crime. In that case the President can be threatened with impeachment (a formal accusation of crimes before the Senate, which would then carry out a trial). It was to avoid impeachment that Richard Nixon resigned in disgrace (August 1974) because of his involvement in the Watergate Scandal. A President’s success has usually depended on how skilful he is at persuading Congress to approve his legislative programme. The Supreme Court keeps a watchful eye on both President and Congress, and can make life difficult for both of them by declaring a law ‘unconstitutional’, which means that it is illegal and has to be changed.

Into the Melting Pot : The Era of Immigration

- A huge wave of immigration

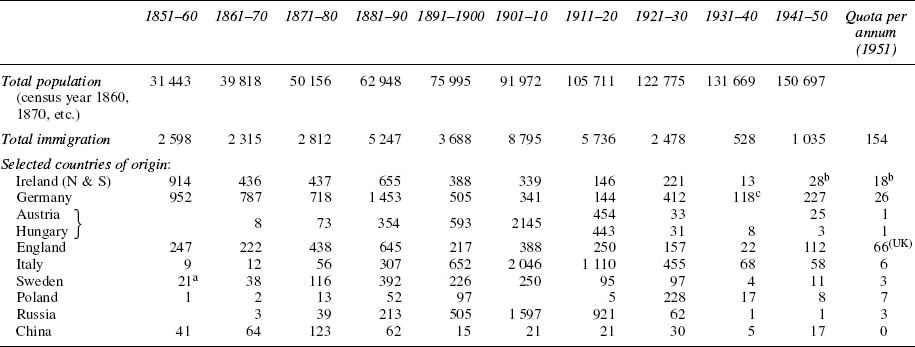

- During the second half of the nineteenth century there was a huge wave of immigration into the USA. People had been crossing the Atlantic to settle in America since the seventeenth century, but in relatively small numbers. During the entire eighteenth century the total immigration into North America was probably no more than half a million; between 1860 and 1930 the total was over 30 million. Between 1840 and 1870 the Irish were the predominant immigrant group. After 1850 Germans and Swedes arrived in vast numbers, and by 1910 there were at least 8 million Germans in the USA. Between 1890 and 1920 it was the turn of Russians, Poles and Italians to come flooding in. Table 22.1 shows in detail the numbers of immigrants arriving in the USA and where they came from.

- Peoples’ motives for leaving their home countries were mixed. Some were attracted by the prospect of jobs and a better life. They hoped that if they could come through the ‘Golden Door’ into the USA, they would escape from poverty. This was the case with the Irish, Swedes, Norwegians and Italians. Persecution drove many people to emigrate; this was especially true of the Jews, who left Russia and other eastern European states in their millions after 1880 to escape pogroms (organized massacres). Immigration was much reduced after 1924 when the US government introduced annual quotas. Exceptions were still made, however, and during the 30 years following the end of the Second World War, a further 7 million people arrived.

- Having arrived in the USA, many immigrants soon took part in a second migration, moving from their ports of arrival on the east coast into the Midwest. Germans, Norwegians and Swedes tended to move westwards, settling in such states as Nebraska, Wisconsin, Missouri, Minnesota, Iowa and Illinois. This was all part of a general American move westwards: the US population west of the Mississippi grew from only about 5 million in 1860 to around 30 million in 1910.

- What were the consequences of immigration?

- The most obvious consequence was the increase in population. It has been calculated that if there had been no mass movement of people to the USA between 1880 and the 1920s, the population would have been 12 per cent lower than it actually was in 1930.

- Immigrants helped to speed up economic development. Economic historian William Ashworth calculated that without immigration, the labour force of the USA would have been 14 per cent lower than it actually was in 1920, and ‘with fewer people, much of the natural wealth of the country would have waited longer for effective use’.

- The movement of people from countryside to town resulted in the growth of huge urban areas, known as ‘conurbations’. In 1880 only New York had over a million inhabitants; by 1910, Philadelphia and Chicago had passed that figure too.

- The movement to take jobs in industry, mining, engineering and building meant that the proportion of the population working in agriculture declined steadily. In 1870, about 58 per cent of all Americans worked in agriculture; by 1914 this had fallen to 14 per cent, and to only 6 per cent in 1965.

- The USA acquired the most remarkable mixture of nationalities, cultures and religions in the world. Immigrants tended to concentrate in the cities, though many Germans, Swedes and Norwegians moved westwards in order to farm. In 1914 immigrants made up over half the population of every large American city, and there were some 30 different nationalities. This led idealistic Americans to claim with pride that the USA was a ‘melting pot’ into which all nationalities were thrown and melted down, to emerge as a single, unified American nation. In fact this seems to have been something of a myth, certainly until well after the First World War. Immigrants would congregate in national groups living in city ghettos. Each new wave of immigrants was treated with contempt and hostility by earlier immigrants, who feared for their jobs. The Irish, for example, would often refuse to work with Poles and Italians. Later the Poles and Italians were equally hostile to Mexicans. Some writers have said that the USA was not really a ‘melting pot’ at all; as historian Roger Thompson puts it,the country was ‘more like a salad bowl, where, although a dressing is poured over the ingredients, they nonetheless remain separate’.

- There was growing agitation against allowing too many foreigners into the USA, and there were demands for the ‘Golden Door’ to be firmly closed. The movement was racial in character, claiming that America’s continuing greatness depended on preserving the purity of its Anglo-Saxon stock, known as White Anglo-Saxon Protestants (WASPS). This, it was felt, would be weakened by allowing the entry of unlimited numbers of Jews and southern and eastern Europeans. From 1921 the US government gradually restricted entry, until it was fixed at 150 000 a year in 1924. This was applied strictly during the depression years of the 1930s when unemployment was high. After the Second World War, restrictions were gradually relaxed; the USA took in some 700 000 refugees escaping from Castro’s Cuba between 1959 and 1975 and over 100 000 refugees from Vietnam after the communists took over South Vietnam in 1975.

US population and immigration, 1851–1950a. Includes Norway for this decade

US population and immigration, 1851–1950a. Includes Norway for this decade

b. Eire only

c. Includes Austria

The USA Becomes Economic Leader of the World

(a) Economic expansion and the rise of big business

In the half-century before the First World War, a vast industrial expansion took the USA to the top of the league table of world industrial producers. The statistics in Table 22.2 show that already in 1900 they had overtaken most of their nearest rivals.

This expansion was made possible by the rich supplies of raw materials – coal, iron ore and oil – and by the spread of railways. The rapidly increasing population, much of it from immigration, provided the workforce and the markets. Import duties (tariffs) protected American industry from foreign competition, and it was a time of opportunity and enterprise. As American historian John A. Garraty puts it: ‘the dominant spirit of the time encouraged businessmen to maximum effort by emphasising progress, glorifying material wealth and justifying aggressiveness’. The most successful businessmen, like Andrew Carnegie (steel), John D. Rockefeller (oil), Cornelius Vanderbilt (shipping and railways), J. Pierpoint Morgan (banking) and P. D. Armour (meat), made vast fortunes and built up huge industrial empires which gave them power over both politicians and ordinary people.

The USA and its chief rivals, 1900

(b) The great boom of the 1920s

After a slow start, as the country returned to normal after the First World War, the economy began to expand again: industrial production reached levels which had hardly been thought possible, doubling between 1921 and 1929 without any great increase in the numbers of workers. Sales, profits and wages also reached new heights, and the ‘Roaring Twenties’, as they became known, gave rise to the popular image of the USA as the world’s most glamorous modern society. There was a great variety of new things to be bought – radio sets, refrigerators, washing machines, vacuum cleaners, smart new clothes, motorcycles, and above all, motor cars. At the end of the war there were already 7 million cars in the USA, but by 1929 there were close on 24 million; Henry Ford led the field with his Model T. Perhaps the most famous of all the new commodities on offer was the Hollywood film industry, which made huge profits and exported its products all over the world. By 1930 almost every town had a cinema. And there were even new forms of music and dance; the 1920s are also sometimes known as the Jazz Age as well as the age of the daring new dances – the Charleston and the Turkey Trot.

What caused the boom?

- It was the climax of the great industrial expansion of the late nineteenth century, when the USA had overtaken her two greatest rivals, Britain and Germany. The war gave American industry an enormous boost: countries whose industries and imports from Europe had been disrupted bought American goods, and continued to do so when the war was over. The USA was therefore the real economic victor of the war.

- The Republican governments’ economic policies contributed to the prosperity in the short term. Their approach was one of laissez-faire, but they did take two significant actions:

- the Fordney–McCumber tariff (1922) raised import duties on goods coming into America to the highest level ever, thus protecting American industry and encouraging Americans to buy home-produced goods;

- a general lowering of income tax in 1926 and 1928 left people with more cash to spend on American goods.

- American industry was becoming increasingly efficient, as more mechanization was introduced. More and more factories were adopting the moving production-line methods first used by Henry Ford in 1915, which speeded up production and reduced costs. Management also began to apply F. W. Taylor’s ‘time and motion’ studies, which saved more time and increased productivity.

- As profits increased, so did wages (though not as much as profits). Between 1923 and 1929 the average wage for industrial workers rose by 8 per cent. Though this was not spectacular, it was enough to enable some workers to buy the new consumer luxuries, often on credit.

- Advertising helped the boom and itself became big business during the 1920s. Newspapers and magazines carried more advertising than ever before, radio commercials became commonplace and cinemas showed filmed advertisements.

- The motor-car industry stimulated expansion in a number of allied industries – tyres, batteries, petroleum for petrol, garages and tourism.

- Many new roads were built and mileage almost doubled between 1919 and 1929. It was now more feasible to transport goods by road, and the numbers of trucks registered increased fourfold during the same period. Prices were competitive and this meant that railways and canals had lost their monopoly.

- Giant corporations with their methods of mass production played an important part in the boom by keeping costs down. Another technique, encouraged by the government, was the trade association. This helped to standardize methods, tools and prices in smaller firms making the same product. In this way the American economy became dominated by giant corporations and trade associations, using mass-production methods for the mass consumer.

(c) Free and equal?

Although many people were doing well during the ‘Roaring Twenties’, the wealth was not shared out equally; there were some unfortunate groups of people who must have felt that their freedom and their liberty did not extend very far. In fact, in many ways it was an age of intolerance.

- Farmers were not sharing in the general prosperity

They had done well during the war, but during the 1920s prices of farm produce gradually fell. Farmers’ profits dwindled and farm labourers’ wages in the Midwest and the agricultural South were often less than half those of industrial workers in the north-east. The cause of the trouble was simple – farmers, with their new combine harvesters and chemical fertilizers, were producing too much food for the home market to absorb. This was at a time when European agriculture was recovering from the war and when there was strong competition from Canada, Russia and Argentina on the world market. It meant that not enough of the surplus food could be exported. The government, with its laissez-faire attitude, did hardly anything to help. Even when Congress passed the McNary–Haugen Bill, designed to allow the government to buy up farmers’ surplus crops, President Coolidge twice vetoed it (1927 and 1928) on the grounds that it would make the problem worse by encouraging farmers to produce even more. - Not all industries were prosperous

Coal mining, for example, was suffering competition from oil, and many workers were laid off. - The black population was left out of the prosperity

In the South, where the majority of black people lived, white farmers always laid off black labourers first. About three-quarters of a million moved north during the 1920s looking for jobs in industry, but they almost always had to make do with the lowest-paid jobs, the worst conditions at work and the worst slum housing. Black people also had to suffer the persecutions of the Ku Klux Klan, the notorious white-hooded anti-black organization, which had about 5 million members in 1924. Assaults, whippings and lynchings were common, and although the Klan gradually declined after 1925, prejudice and discrimination against black people and against other coloured and minority groups continued. - Hostility to immigrants

Immigrants, especially those from eastern Europe, were treated with hostility by descendants of the original white settlers who came from Britain and the Netherlands. These WASPS – White Anglo-Saxon Protestants – felt under threat from the enormous numbers of immigrants. These included Catholic Irish and Italians and Orthodox and Jewish Russians, together with Poles and Hungarians. It was thought that, not being Anglo-Saxon, these people were threatening the American way of life and the greatness of the American nation. In 1924 the Johnson–Reed Act set an annual quota of 150 000 immigrants. - Super-corporations

Industry became increasingly monopolized by large trusts or super-corporations. By 1929 the wealthiest 5 per cent of corporations took over 84 per cent of the total income of all corporations. Although trusts increased efficiency, there is no doubt that they kept prices higher, and wages lower than was necessary. They were able to keep trade unions weak by forbidding workers to join. The Republicans, who were pro-business, did nothing to limit the growth of the super-corporations because the system seemed to be working well. - Widespread poverty in industrial areas and cities

Between 1922 and 1929, real wages of industrial workers increased by only 1.4 per cent a year; 6 million families (42 per cent of the total) had an income of less than $1000 a year. Working conditions were still appalling – about 25 000 workers were killed at work every year and 100 000 were disabled. After touring working-class areas of New York in 1928, Congressman La Guardia remarked: ‘I confess I was not prepared for what I actually saw. It seemed almost unbelievable that such conditions of poverty could really exist.’ In New York City alone there were 2 million families, many of them immigrants, living in slum tenements that had been condemned as firetraps. - The freedom of workers to protest was extremely limited

Strikes were crushed by force, militant trade unions had been destroyed and the more moderate unions were weak. Although there was a Socialist Party, there was no hope of it ever forming a government. After a bomb exploded in Washington in 1919, the authorities whipped up a ‘Red Scare’; they arrested and deported over 4000 citizens of foreign origin, many of them Russians, who were suspected of being communists or anarchists. Most of them, in fact, were completely innocent. - Prohibition was introduced in 1919

This ‘noble experiment’, as it was known, was the banning of the manufacture, import and sale of all alcoholic liquor. It was the result of the efforts of a well-meaning pressure group before and during the First World War, which believed that a ‘dry’ America would mean a more efficient and moral America. But it proved impossible to eliminate ‘speakeasies’ (illegal bars) and ‘bootleggers’ (manufacturers of illegal liquor), who protected their premises from rivals with hired gangs, who shot each other up in gunfights. Organized crime was rife and gang violence became part of the American scene, especially in Chicago. It was there that Al Capone made himself a fortune, much of it from speakeasies and protection rackets. It was there too that the notorious St Valentine’s Day Massacre took place in 1929, when hitmen hired by Capone arrived in a stolen police car and gunned down seven members of a rival gang who had been lined up against a wall.

The row over Prohibition was one aspect of a traditional American conflict between the countryside and the city. Many country people believed that city life was sinful and unhealthy, while life in the country was pure, noble and moral. President Roosevelt’s administration ended Prohibition in 1933, since it was obviously a failure and the government was losing large amounts of revenue that it would have collected from taxes on liquor. - Women not treated equally

Many women felt that they were still treated as second-class citizens. Some progress had been made towards equal rights for women: they had been given the vote in 1920, the birth control movement was spreading and more women were able to take jobs. On the other hand, these were usually jobs men did not want; women were paid lower wages than men for the same job, and education for women was still heavily slanted towards preparing them to be wives and mothers rather than professional career women.

Socialists, Trade Unions and the Impact of War and The Russian Revolutions

- Labour unions during the nineteenth century

During the great industrial expansion of the half-century after the Civil War, the new class of industrial workers began to organize labour unions to protect their interests. Often the lead was taken by immigrant workers who had come from Europe with experience of socialist ideas and trade unions. It was a time of trauma for many workers in the new industries. On the one hand there were the traditional American ideals of equality, the dignity of the worker and respect for those who worked hard and achieved wealth – ‘rugged individualism’. On the other hand there was a growing feeling, especially during the depression of the mid-1870s, that workers had lost their status and their dignity. Hugh Brogan neatly sums up the reasons for their disillusionment:

Diseases (smallpox, diphtheria, typhoid) repeatedly swept the slums and factory districts; the appalling neglect of safety precautions in all the major industries; the total absence of any state-assisted schemes against injury, old age or premature death; the determination of employers to get their labour as cheap as possible, which meant, in practice, the common use of under-paid women and under-age children; and general indifference to the problems of unemployment, for it was still the universal belief that in America there was always work, and the chance of bettering himself, for any willing man.

As early as 1872 the National Labor Union (the first national federation of unions) led a successful strike of 100 000 workers in New York, demanding an eight-hour working day. In 1877 the Socialist Labor Party was formed, its main activity being to organize unions among immigrant workers. In the early 1880s an organization called the Knights of Labor became prominent. It prided itself on being non-violent, non-socialist and against strikes, and by 1886 it could boast more than 700 000 members. Soon after that, however, it went into a steep decline. A more militant, though still moderate, organization was the American Federation of Labor (AFL), with Samuel Gompers as its president. Gompers was not a socialist and did not believe in class warfare; he was in favour of working with employers to get concessions, but equally he would support strikes to win a fair deal and improve the workers’ standard of living.

When it was discovered that on the whole, employers were not prepared to make concessions, Eugene Debs founded a more militant association – the American Railway Union (ARU) – in 1893, but that too soon ran into difficulties and ceased to be important. Most radical of all were the Industrial Workers of the World (known as the Wobblies), a socialist organization. Started in 1905, they led a series of actions against a variety of unpopular employers, but were usually defeated. None of these organizations achieved very much that was tangible, either before or after the First World War, though arguably they did draw the public’s attention to some of the appalling conditions in the world of industrial employment. There were several reasons for their failure.The employers and the authorities were completely ruthless in suppressing strikes, blaming immigrants for what they called ‘un-American activities’ and labelling them as socialists. Respectable opinion regarded unionism as something unconstitutional which ran counter to the cult of individual liberty. The general middle-class public and the press were almost always on the side of the employers, and the authorities had no hesitation in calling in state or federal troops to ‘restore order’.

The American workforce itself was divided, the skilled workers against the unskilled, which meant that there was no concept of worker solidarity; the unskilled worker simply wanted to become a member of the skilled elite.

There was a division between white and black workers; most unions refused to allow blacks to join, and told them to form their own unions. For example, blacks were not allowed to become members of the new ARU in 1894, although Debs wanted to bring everybody in. In retaliation the black unions often refused to cooperate with the whites, and allowed themselves to be used as strike-breakers.

Each new wave of immigrants weakened the union movement; they were willing to accept lower wages than established workers and so could be used as strike-breakers.

In the early years of the twentieth century, some union leaders, especially those of the AFL, were discredited: they were becoming wealthy, paying themselves large salaries, and seemed to be on suspiciously close terms with employers, while ordinary union members gained very little benefit and working conditions hardly improved. The union lost support because it concentrated on looking after skilled workers; it did very little for unskilled, black and women workers, who began to look elsewhere for protection.

Until after the First World War it was the American farmers, not the industrial workers, who made up a majority of the population. Later it was the middle class, white-collar workers, who narrowly became the largest group in American society.

The unions under attack

The employers, fully backed by the authorities, soon began to react vigorously against strikes, and the penalties for strike leaders were severe. In 1876 a miners’ strike in Pennsylvania was crushed and ten of the leaders (members of a mainly Irish secret society known as the Molly Maguires) were hanged for allegedly committing acts of violence, including murder. The following year there was a series of railway strikes in Pennsylvania; striking workers clashed with police, and the National Guard was brought in. The fighting was vicious: two companies of US infantry had to be called in before the workers were finally defeated. Altogether that year, about 100 000 railway workers had gone on strike, over a hundred were killed, and around a thousand sent to jail. The employers made a few minor concessions, but the message was clear: strikes would not be tolerated.

Ten years later nothing had changed. In 1886, organized labour throughout the USA campaigned for an eight-hour working day. There were many strikes and a few employers granted a nine-hour day to dissuade their workers from striking. However, on 3 May, police killed four workers in Chicago. The following day, at a large protest meeting in Haymarket Square, a bomb exploded in the middle of a contingent of police, killing seven of them. Who was responsible for the bomb was never discovered, but the police arrested eight socialist leaders in Chicago. Seven of them were not even at the meeting; but they were found guilty and four were hanged. The campaign failed.

Another strike, which became legendary, took place in 1892 at the Carnegie steelworks in Homestead, near Pittsburgh. When the workforce refused to accept wage reductions, the management laid them all off and tried to bring in strike-breakers, protected by hired detectives. Almost the entire town supported the workers; fighting broke out as crowds attacked the detectives, and several people were killed. Eventually troops were brought in and both the strike and the union were broken. The strike leaders were arrested and charged with murder and treason against the state, but the difference this time was that sympathetic juries acquitted them all.

In 1894 it was the turn of Eugene Debs and his American Railway Union. Outraged by the treatment of the Homestead workers, he organized a strike of workers at the Pullman Palace Car Company’s Chicago plant, who had just had their wages reduced by 30 per cent. ARU members were ordered not to handle Pullman cars, which meant in effect that all passenger trains in the Chicago area were brought to a standstill. Strikers also blocked tracks and derailed wagons. Once again, federal troops were brought in, and 34 people were killed; the strike was crushed and nothing much more was heard from the ARU. In a way Debs was fortunate: he was only given six months in prison, and during that time, he later claimed, he was converted to socialism.

Socialism and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW)

A new and more militant phase of labour unionism began in the early years of the twentieth century, with the formation of the IWW in Chicago in 1905. Eugene Debs, who was by this time the leader of the Socialist Party, was at the inaugural meeting, and so was ‘Big Bill’ Haywood, a miners’ leader, who became the main driving force behind the IWW. It included socialists, anarchists and radical trade unionists; their aim was to form ‘One Big Union’ to include all workers across the country, irrespective of race, sex or level of employment. Although they were not in favour of starting violence, they were quite prepared to resist if they were attacked. They believed in strikes as an important weapon in the class war; but strikes were not the main activity: ‘they are tests of strength in the course of which the workers train themselves for concerted action, to prepare for the final “catastrophe” – the general strike which will complete the expropriation of the employers’.

This was fighting talk, and although the IWW never had more than 10 000 members at any one time, employers and property owners saw them as a threat to be taken seriously. They enlisted the help of all possible groups to destroy the IWW. Local authorities were persuaded to pass laws banning meetings and speaking in public; gangs of vigilantes were hired to attack IWW members; leaders were arrested. In Spokane, Washington, in 1909, 600 people were arrested and jailed for attempting to make public speeches in the street; eventually, when all the jails were full, the authorities relented and granted the right to speak.

Undeterred, the IWW continued to campaign, and over the next few years members travelled around the country to organize strikes wherever they were needed – in California, Washington State, Massachusetts, Louisiana and Colorado, among other places. One of their few outright successes came with a strike of woollen weavers in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1912. The workers, mainly immigrants, walked out of the factories after learning that their wages were to be reduced. The IWW moved in and organized pickets, parades and mass meetings. Members of the Socialist Party also became involved, helping to raise funds and make sure the children were fed. The situation became violent when police attacked a parade; eventually state militia and even federal cavalry were called in, and several strikers were killed. But they held out for over two months until the mill owners gave way and made acceptable concessions.

However, successes like this were limited, and working conditions generally did not improve. In 1911 a fire in a New York shirtwaist factory killed 146 workers, because employers had ignored the fire regulations. At the end of 1914 it was reported that 35 000 workers had been killed that year in industrial accidents. Many of those sympathetic to the plight of the workers began to look towards the Socialist Party and political solutions. A number of writers helped to increase public awareness of the problems. For example, Upton Sinclair’s novel The Jungle (1906) dealt with the disgusting conditions in the meat-packing plants of Chicago, and at the same time succeeded in putting across the basic ideals of socialism.

By 1910 the party had some 100 000 members and Debs ran for president in 1908, though he polled only just over 400 000 votes. The importance of the socialist movement was that it publicized the need for reform and influenced both major parties, which acknowledged, however reluctantly, that some changes were needed, if only to steal the socialists’ thunder and beat off their challenge. Debs ran for president again in 1912, but by that time the political scene had changed dramatically. The ruling Republican Party had split: its more reform-minded members set up the Progressive Republican League (1910) with a programme that included the eight-hour day, prohibition of child labour, votes for women and a national system of social insurance. It even expressed support for labour unions, provided they were moderate in their behaviour. The Progressives decided to run former president Theodore Roosevelt against the official Republican candidate William Howard Taft. The Democrat Party also had its progressive wing, and their candidate for president was Woodrow Wilson, a well-known reformer who called his programme the ‘New Freedom’.

Faced with these choices, the American Federation of Labor stayed with the Democrats as the most likely party to actually carry out its promises, while the IWW supported Debs. With the Republican vote divided between Roosevelt (4.1 million) and Taft (3.5 million), Wilson was easily elected president (6.3 million votes). Debs (900 672) more than doubled his previous vote, indicating that support for socialism was still increasing despite the efforts of the progressives in both major parties. During Wilson’s presidency (1913–21) a number of important reforms were introduced, including a law forbidding child labour in factories and sweatshops. More often than not, however, it was the state governments which led the way; for example, by 1914, nine states had introduced votes for women; it was only in 1920 that women’s suffrage became part of the federal constitution. Hugh Brogan sums up Wilson’s reforming achievement succinctly: ‘By comparison with the past, his achievements were impressive; measured against what needed to be done, they were almost trivial.’

The First World War and the Russian revolutions

When the First World War began in August 1914, Wilson pledged, to the relief of the vast majority of the American people, that the USA would remain neutral. Having won the 1916 election largely on the strength of the slogan ‘He Kept Us Out of the War’, Wilson soon found that Germany’s campaign of ‘unrestricted’ submarine warfare gave him no alternative but to declare war. The Russian revolution of February/March 1917, which overthrew Tsar Nicholas II, came at exactly the right time for the president – he talked of ‘the wonderful and heartening things that have been happening in the last few weeks in Russia’. The point was that many Americans had been unwilling for their country to enter the war because it meant being allied to the most undemocratic state in Europe. Now that tsarism was finished, an alliance with the apparently democratic Provisional Government was much more acceptable. Not that the American people were enthusiastic about the war; according to Howard Zinn:

There is no persuasive evidence that the public wanted war. The government had to work hard to create its consensus. That there was no spontaneous urge to fight is suggested by the strong measures taken: a draft of young men, an elaborate propaganda campaign throughout the country, and harsh punishment for those who refused to get in line.

Wilson called for an army of a million men, but in the first six weeks, a mere 73000 volunteered; Congress voted overwhelmingly for compulsory military service.

The war gave the Socialist Party a new lease of life – for a short time. It organized anti-war meetings throughout the Midwest and condemned American participation as ‘a crime against the people of the United States’. Later in the year, ten socialists were elected to the New York State legislature; in Chicago the socialist vote in the municipal elections rose from 3.6 per cent in 1915 to 34.7 per cent in 1917. Congress decided to take no chances – in June 1917 it passed the Espionage Act, which made it an offence to attempt to cause people to refuse to serve in the armed forces; the socialists came under renewed attack: anyone who spoke out against conscription was likely to be arrested and accused of being pro-German. About 900 people were sent to jail under the Espionage Act, including members of the IWW, which also opposed the war.

Events in Russia influenced the fortunes of the socialists. When Lenin and the Bolsheviks seized power in October/November 1917, they soon ordered all Russian troops to cease fire, and began peace talks with the Germans. This caused consternation among Russia’s allies, and the Americans condemned the Bolsheviks as ‘agents of Prussian imperialism’. There was plenty of public support when the authorities launched a campaign against the Socialist Party and the IWW, who were both labelled as pro-German Bolsheviks. In April 1918, 101 ‘Wobblies’, including their leader, ‘Big Bill’ Haywood, were put on trial together. They were all found guilty of conspiring to obstruct recruitment and encourage desertion. Haywood and 14 others were sentenced to 20 years in jail; 33 others were given ten years and the rest received shorter sentences. The IWW was destroyed. In June 1918, Eugene Debs was arrested and accused of trying to obstruct recruitment and of being pro-German; he was sentenced to ten years in prison, though he was released after serving less than three years. The war ended in November 1918, but in that short period of US involvement, since April 1917, some 50 000 American soldiers had died.

The Red Scare: the Sacco and Vanzetti case

Although the war was over, the political and social troubles were not. In the words of Howard Zinn, ‘with all the wartime jailings, the intimidation, the drive for national unity, the Establishment still feared socialism. There seemed to be again the need for the twin tactics of control in the face of revolutionary challenge: reform and repression.’ The ‘revolutionary challenge’ took the form of a number of bomb outrages during the summer of 1919. An explosion badly damaged the house of the attorney-general, A. Mitchell Palmer, in Washington, and another bomb went off at the great House of Morgan banking establishment on Wall Street, in New York, killing 39 people and injuring hundreds. Exactly who was responsible has never been discovered, but the explosions were blamed on anarchists, Bolsheviks and immigrants. ‘This movement,’ one of Wilson’s advisers told him, ‘if it is not checked, is bound to express itself in an attack on everything we hold dear.’

Repression soon followed. Palmer himself whipped up the ‘Red Scare’ – the fear of Bolshevism – according to some sources, in order to gain popularity by handling the situation decisively. He was ambitious, and fancied himself as a presidential candidate in the 1920 elections. In lurid language, he described the ‘Red Threat’, which, he said, was ‘licking the altars of our churches, crawling into the sacred corners of American homes, seeking to replace the marriage vows … it is an organization of thousands of aliens and moral perverts’. Although he was a Quaker, Palmer was extremely aggressive; he leapt into the attack during the autumn of 1919, ordering raids on publishers’ offices, union and socialist headquarters, public halls, private houses, and meetings of anyone who was thought to be guilty of Bolshevik activities. Over a thousand anarchists and socialists were arrested, and some 250 aliens of Russian origin were rounded up and deported to Russia. In January 1920 a further 4000 mostly harmless and innocent people were arrested, including 600 in Boston, and most of them were deported after long periods in jail.

One case above all caught the public’s imagination, not only in America but worldwide: the Sacco and Vanzetti affair. Arrested in Boston in 1919, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were charged with robbing and murdering a postmaster. They were found guilty, though the evidence was far from convincing, and sentenced to death. However, the trial was something of a farce; the judge, who was supposed to be neutral, showed extreme prejudice against them on the grounds that they were anarchists and Italian immigrants who had somehow avoided military service. After the trial he boasted of what he had done to ‘those anarchist bastards … sons of bitches and Dagoes’.

Sacco and Vanzetti appealed against their sentences and spent the next seven years in jail while the case dragged on. Their friends and sympathizers succeeded in arousing worldwide support, especially in Europe. Famous supporters included Stalin, Henry Ford, Mussolini, Fritz Kreisler (the world-famous violinist), Thomas Mann, Anatole France and H. G. Wells. There were massive demonstrations outside the US embassy in Rome and bombs exploded in Lisbon and Paris. In the USA itself, the campaign for their release gathered momentum; a support fund was opened for their families and demonstrations were organized outside the jail where they were being held. It was all to no avail: in April 1927 the Governor of Massachusetts decreed that the guilty verdicts should stand. In August Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in the electric chair, protesting their innocence to the end.

The whole affair provided great adverse publicity for the USA; it seemed clear that Sacco and Vanzetti had been made scapegoats because they were anarchists and immigrants. There was outrage in Europe and further protest demonstrations were held after their execution. Nor were anarchists and immigrants the only classes of people who felt persecuted; black people too continued to have a hard time in the so-called classless society of the USA.

|

50 videos|70 docs|30 tests

|