Economic Impact of British Colonial Rule - UPSC PDF Download

The First Phase of British Colonialism

- The first phase of British colonialism in India is generally considered to have begun in 1757, when the British East India Company acquired the rights to collect revenue from its territories in the eastern and southern parts of the subcontinent. This phase lasted until 1813, when the company's monopoly over trade with India ended.

- Initially, the British arrived in India during the 17th century as a trading company, backed by an exclusive royal charter from Queen Elizabeth I to conduct trade with India. Their first trading post, or "factory," was established along the Hughli River in Bengal. The company managed to obtain permits, or "dastak," from the Mughal emperor, exempting it from paying duties on its trade. However, this led to widespread corruption among company employees, who misused the permits for their private trade, resulting in significant revenue losses for Bengal's governors (later known as nawabs) in the form of customs duties. This issue was a major factor leading to the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

- During this period, the primary function of the British East India Company was to purchase spices, cotton, and silk from India and sell them at substantial profits in the large British market. This trade resulted in significant amounts of bullion flowing from Britain to India to pay for these goods. The company struggled to find British products that could be sold in India in exchange to stem this outflow of bullion. In addition to spending on purchasing commodities, the company also incurred significant expenses in wars against other European powers, such as the Portuguese, Dutch, and French, who were also seeking the same goods for trade.

- The acquisition of "diwani" (the right to collect revenue) in Bengal after the Battle of Buxar, which followed the Battle of Plassey, provided the company with the means to raise money for its expenditures in India.

Land Revenue Policies

- After the diwani of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa was granted to the East India Company in 1765, the maximization of revenue from the colony became the primary objective of the British administration. Agricultural taxation was the main source of income for the company, which had to pay dividends to its investors in Britain.

Zamindari System was the 1st experiment

Zamindari System was the 1st experiment

- The British administration in India conducted various land revenue experiments to determine the relationship between the colonial state and the local population. One such experiment was the introduction of revenue farming in Bengal in 1772 by Governor Warren Hastings. This system allowed European District Collectors to auction the right to collect revenue to the highest bidder. However, this system failed due to high revenue demands, leading to the implementation of the Permanent Settlement system in 1793 by Cornwallis. This new system made 'zamindars' landowners and fixed the state's land revenue demand permanently. The intention was to create a class of landowners who would improve crop production and become loyal to the British administration. Unfortunately, this system led to the impoverishment of tenant-cultivators and the collapse of many traditional zamindar houses, as well as creating intermediaries between the zamindar and cultivator.

- To counteract these issues, the Ryotwari System was introduced in the Madras Presidency in 1792 by Alexander Read, and later in the Bombay Presidency. This system assessed each cultivator or 'ryot' individually, making them property owners instead of zamindars. Although this increased the state's revenue, the assessments were flawed, and peasants were overburdened by taxes. Furthermore, the system did not eliminate the presence of landed intermediaries. In northern and northwest India, the Mahalwari Settlement was followed after 1822, which involved the state making settlements with either village communities or traditional 'taluqdars.' This system recognized collective proprietary rights but also resulted in the stagnation of agriculture and the entrenchment of moneylenders in rural areas.

- The British revenue policies in India not only impacted the local population but also had significant effects on the British economy. The acquisition of diwani rights allowed the British East India Company to extract wealth from local rulers, zamindars, and merchants, particularly in Bengal. This wealth, including illegal incomes of company officials, was used to fuel the Industrial Revolution in Britain. The extraction of wealth from India and the aggressive land revenue policies also contributed to the territorial expansion of British rule in the region.

The Second Phase of British Colonialism (Free Trade)

- The 'Second Phase' of British colonialism, also known as the Free Trade era, began with the Charter Act of 1813 and ended in 1858 when the British Crown assumed direct control over all British territories in India. The East India Company had initially enjoyed a monopoly on trade and strong support from the British government. However, this support waned as industrialization in Britain led to a shift in the composition of the parliament.

- Influenced by Adam Smith's book, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, a new school of economic thought emerged, which criticized the concept of exclusive monopolies and advocated for a 'free trade' or 'laissez faire' government policy. As a result, the British parliament sought to exert greater control over the East India Company's profits and began targeting individual company officials with accusations of misconduct.

- The Free Traders, who had gained prominence in the British parliament by the beginning of the 19th century, pushed for unrestricted access to India. This pressure led to the passing of the Charter Act of 1813, which ended the East India Company's monopoly in India and subordinated its territorial possessions to the British Crown's sovereignty.

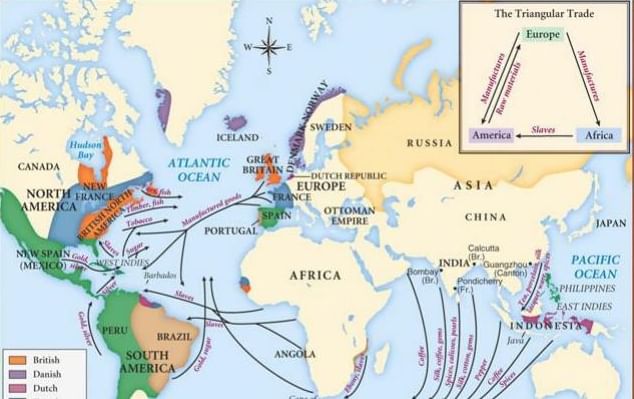

World Trade in 18th Century with India

World Trade in 18th Century with India

- ‘Free Trade’ changed the nature of the Indian colony completely, through a dual strategy. Firstly it threw open Indian markets for the entry of cheap, mass-produced, machine-made British goods, which enjoyed little or almost no tariff restrictions. The passage of expensive, hand-crafted Indian textiles to Britain, which had been very popular there, was however obstructed by prohibitive tariff rates.

- And secondly British-Indian territory was developed as a source of food stuff and raw material for Britain, which fuelled rapid growth in its manufacturing sector, crucial to the emergence of a powerful capitalist economy. These changes reversed the favourable balance of trade that India had enjoyed earlier. This phase laid the foundations of a classic colonial economy within India through the complex processes of commercialization of agriculture and deindustrialization, which are discussed below.

Commercialization of Agriculture

- The commercialization of agriculture in India during the colonial period is often thought to have improved the situation for many peasants. Beginning in the 1860s, agricultural production was heavily influenced by the demands of foreign markets for Indian primary products. Cash crops like indigo, opium, cotton, and silk were exported in the first half of the 19th century, and later replaced by raw jute, food grains, oil seeds, and tea. Raw cotton remained the most sought-after product. This growth in cash crop production coincided with the construction of railways after 1850, which facilitated trade networks.

- However, the commercialization of agriculture appears to have been a forced and artificial process that resulted in limited growth within the sector. It led to some differentiation in agriculture but did not create a 'capitalist landowner' figure, as was the case in Britain. The absence of large-scale industrial development meant that the accumulated wealth from agriculture had no viable channels for investment in industry. Additionally, expanding the capacity and organization of agriculture was risky due to fluctuating prices in distant foreign markets and a lack of protection from the colonial state.

- As a result, commercialization increased sub-infeudation in rural areas, and money was channeled into trade and usury. The majority of profits from export trade went to British businesses, which controlled shipping and insurance industries, as well as commission agents, traders, and bankers. Those who benefited within the colony were mainly large farmers, some Indian traders, and moneylenders. Commercialization also intensified the exploitation of rural areas by feudal landlords and moneylenders.

- The so-called commercialization process, which was expected to lead to capitalist agriculture, often involved exploitative and nearly unfree labor practices. Tea plantations in Assam were owned by whites, who used indentured labor, which was comparable to slavery. White planters had to force farmers to grow indigo because it provided low returns and disrupted the harvest cycle. This led to extreme coercion and eventually sparked the indigo rebellion in 1859-60.

- While commercialization did result in some short-term successes in cotton production in western India and jute production in eastern India, this was mainly due to increased demand rather than innovation in production and organization. Farmers were often compelled to grow cash crops in order to pay high revenues, rents, and debts in cash. This shift from food crops like jowar, bajra, and pulses to cash crops frequently led to disaster during famine years.

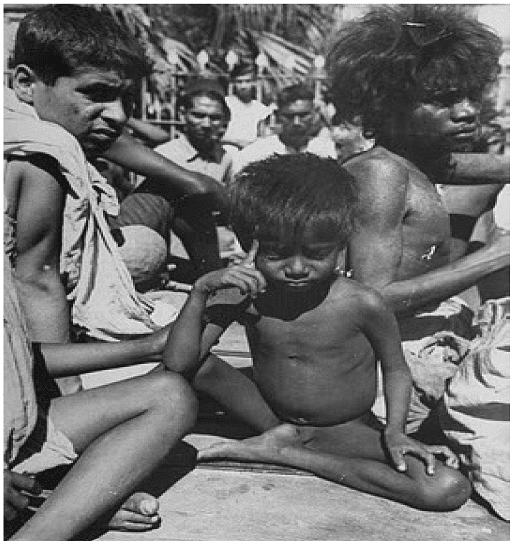

- A decline in global demand for Indian cotton in the 1870s resulted in heavy debt, famine, and agrarian riots in the Deccan cotton belt. The jute industry collapsed in the 1930s, followed by a devastating famine in Bengal in 1943. While the causes of these famines have been widely debated by historians, it is clear that overall food crop production lagged behind population growth, leading to the deaths of millions due to starvation and epidemics.

Bengal Famine 1943

Bengal Famine 1943

The Third Phase of British Colonialism

- The third phase of British colonialism, which began in the 1860s, was marked by the expansion of the British empire and the direct control of British India under the British crown. This period saw an increase in finance-imperialism, with British capital being invested in the colony through a closed network of banks, export-import firms, and managing agencies. The third phase also saw heightened rivalry between developed and industrialized countries, such as France, Belgium, Germany, the United States, and Japan, for colonies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. As a result, Britain's dominance in the world market dwindled, leading to a search for new markets and sources of raw materials.

- India played a crucial role in solving Britain's trade deficits and providing a captive market for British manufactured goods. The control over India ensured a steady inflow of raw materials to support the expansion of industrial production. However, this control also led to the impoverishment of indigenous handicrafts and a lack of modern industry development in the colony. Though the colonial government claimed to support free trade, indigenous enterprises faced discrimination and obstacles perpetuated by the state's policies.

- Despite the challenges, Indian entrepreneurs found opportunities to grow during periods of British economic hardship. The First World War saw the emergence of Indian businessmen, such as G.D. Birla and Swarupchand Hukumchand, investing in various industries like jute, coal mines, sugar mills, and paper. Moreover, the cotton industry in western India flourished during the war years, eventually competing with Lancashire. However, the overall success of these ventures remained confined to the domestic market, and the potential for growth was limited due to the widespread poverty in India.

- Early Indian nationalists, such as Dadabhai Naoroji, M.G. Ranade, and R.C. Dutt, had expected Britain to undertake capitalist industrialization in India but were disappointed with the outcomes of colonial industrial policies. They formulated a strong economic critique of colonialism in the late nineteenth century, with Naoroji putting forward the "drain of wealth" theory. This theory argued that India's poverty was a result of the steady drain of Indian wealth into Britain due to British colonial policy.

Dadabhai Naoroji commented his famous "Drain of Wealth" Theory

Dadabhai Naoroji commented his famous "Drain of Wealth" Theory

- The drain of wealth from India during the British colonial rule occurred through various means, such as interest payments on foreign debts of the East India Company, military expenditure, guaranteed returns on foreign investment in infrastructure, import of stationery from England, and payments for the British administration's staffing and pension costs. This drain of wealth, even if small, could have been invested within India to generate a surplus and build a capitalist economy. The question arises whether there was any development in India during this time.

- Before the British colonial rule, eighteenth-century Mughal India was experiencing economic growth rather than stagnation or crisis, with regions generating and accumulating surplus through agriculture and cash nexus. However, 200 years of British colonialism left the country backward and impoverished. While the British did attempt to modernize India, these efforts were primarily motivated by benefiting their own economy. This backwardness in India was a necessary consequence of the Industrial Revolution in Britain and their interconnected economies through "free trade." Therefore, when India gained independence in 1947, it began its process of modernization from a colonial mode rather than a traditional mode, which was inherently backward and underdeveloped.

Conclusion

In conclusion, British colonialism in India can be divided into three overlapping phases, each marked by distinct economic policies and consequences. The initial phase saw the British East India Company focusing on trade and revenue collection, leading to the establishment of systems like the Zamindari and Ryotwari systems. The second phase, characterized by 'Free Trade,' led to the commercialization of agriculture and deindustrialization in India, with a focus on serving Britain's economic interests. The third phase, marked by finance-imperialism, saw limited growth in Indian industries, primarily serving the domestic market. Despite some markers of success, the overall impact of British colonialism left India structurally backward and underdeveloped. Upon gaining independence in 1947, India embarked on a modernization process from a colonial mode rather than a traditional one.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) of Economic Effects of British Colonialism

What was the first phase of British colonialism in India?

The first phase of British colonialism in India is generally dated from 1757, when the British East India Company acquired the rights to collect revenue from its territories in the eastern and southern parts of the subcontinent, to 1813, when the Company's monopoly over trade with India came to an end. During this phase, the primary function of the British East India Company was to buy spices, cotton, and silk from India and sell them at huge profits in Britain.

What were the various land revenue policies implemented by the British in India?

The British administration experimented with various land revenue policies, such as the Zamindari System, Ryotwari System, and Mahalwari Settlement. These policies determined the relationship between the colonial state and the people it governed and aimed to maximize revenue from the agricultural sector.

What was the second phase of British colonialism in India?

The second phase of British colonialism in India began with the Charter Act of 1813, which ended the Company's monopoly trading rights and subordinated its territorial possessions to the overall sovereignty of the British crown. This phase saw the introduction of "Free Trade," which changed the nature of the Indian colony by opening Indian markets for the entry of cheap, mass-produced, machine-made British goods and developing British-Indian territory as a source of foodstuffs and raw materials for Britain.

What was the impact of commercialization of agriculture on Indian farmers?

Commercialization of agriculture led to differentiation within the agricultural sector but did not create the figure of the 'capitalist landowner' as in Britain. The lack of any simultaneous large-scale industrial development meant that accumulated agrarian capital had no viable channels of investment, leading to increased sub-infeudation in the countryside and money being channelized into trade and usury. Commercialization also intensified the feudal structure of landlord-moneylender exploitation in rural areas.

What was the third phase of British colonialism in India?

The third phase of British colonialism in India began from the 1860s when British India became part of the ever-expanding British empire and was placed directly under the control and sovereignty of the British crown. This period was one of 'finance-imperialism,' when some British capital was invested in the colony. This phase saw an intensification of the rivalry between developed and industrialized countries for colonies in Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

FAQs on Economic Impact of British Colonial Rule - UPSC

| 1. What were the economic effects of British colonialism? |  |

| 2. How did British colonialism impact the local industries in the colonies? |  |

| 3. Did British colonialism lead to economic growth in the colonies? |  |

| 4. How did British colonialism impact the agricultural sector in the colonies? |  |

| 5. How did British colonialism contribute to the global trade network? |  |