The Structuralism | Anthropology Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Introduction

Structuralism is the name given to a method of analysing social relations and cultural products, which came into existence in the 1950s. Although it had its origin in linguistics, particularly from the work of Ferdinand de Saussure, it acquired popularity in anthropology, from where it impacted the other disciplines in social sciences and humanities. It gives primacy to pattern over substance. The meaning of a particular phenomenon or system comes through knowing how things fit together, and not from understanding things in isolation. A characteristic that structuralism and structural-functional approach share in common is that both are concerned with relations between things.

However, there are certain dissimilarities between the two. Structural-functional approach is interested in finding order within social relations. Structuralism, on the other hand, endeavours to find the structures of thought and the structure of society. Structural-functional approach follows inductive reasoning; from the particular, it moves to the general. Structuralism subscribes to deductive logic. It begins with certain premises. They are followed carefully to the point they lead to. Aspects from geometry and algebra are kept in mind while working with structuralism. For structuralism, logical possibilities are worked out first and then it is seen, how reality fits. For true structuralists, there is no reality except the relations between things.

Claude Levi-Strauss: His Life and Works

Claude Levi-Strauss (1908-2009) is often described as the ‘last French intellectual giant’, the ‘founder of structuralism in anthropology’, and the ‘father of modern anthropology’. Born on 28 November 1908 in Belgium, he was one of the greatest social anthropologists of the twentieth century, ruling the intellectual circles from the 1950s to the 1980s, after which the popularity of his method (known as structuralism) depressed with new approaches and paradigms taking its place, but he never went to the backseat. Even when structuralism did not have many admirers, it was taught in courses of sociology and anthropology and the author whose work was singularly attended to was none other than Lévi-Strauss. Each year he was read by scholars from anthropology and the other disciplines with new insights and renewed interest, since he was one of the few anthropologists whose popularity spread beyond the confines of social anthropology. He was (and is) read avidly in literature. Although he did not do, at one time, it was thought that every social fact, and every product of human activity and mind, of any society, simple or complex, could be analysed following the method that Lévi-Strauss had proposed and defended. In 1935, Lévi-Strauss got an appointment at the University of São Paulo to teach sociology. His stay in Brazil exposed him to the ‘anthropological other’. He had already read Robert Lowie’s Primitive Society and formed a conception of how anthropological studies were to be carried out. Lévi-Strauss said: “I had gone to Brazil because I wanted to become an anthropologist. And I had been attracted to an anthropology very different from that of Durkheim, who was not a field worker, while I was learning about fieldwork through the English and the Americans.” During the first year of his stay in the University, he started ethnographic projects with his students, working on the folklore of the surrounding areas of São Paulo. He then went to the Mato Grosso among the Caduveo and Bororo tribes; he described his first fieldwork in the following words: “I was in a state of intense intellectual excitement. I felt I was reliving the adventures of the first sixteenth century explorers. I was discovering the New World for myself. Everything seemed mythical the scenery, the plants, the animal.

From his field stay with the Caduveo, he brought decorated pottery and hides painted with motifs, and from Bororo, the ornaments made of feathers, animal teeth and claws. Some of the exhibits that he had brought were, in his words, ‘truly spectacular’. He put up an exhibition of these objects in 1936, on the basis of which he got a grant from Musée de L’Homme (which later became Centre National de la Recherch Scientifique) to carry out a field expedition to the Nambikwara.

A big article that Lévi-Strauss wrote on the Bororo (which appeared in the Journal de la Sociéte des Américanistes) attracted the attention of Robert Lowie, who invited him to the New School of Social Research to take up a teaching assignment. Lévi-Strauss’s stay in New York was extremely fruitful. He had a chance to look at the rich material that the American anthropologists had collected on the Indian communities. He went about analysing it, but at the same time carried several short first-hand field studies, although they were not of the same league as was the masterly fieldwork that Bronislaw Malinowski had carried out among the Trobriand Islanders. However, whatever fieldwork he carried out, he thought, was enough to give him an insight into the ‘other’. He saw himself as an analyst and a synthesizer of the material that had already been collected. Since his aim was to understand the working of the human mind, he wanted to have a look at the ethnographic facts and the material cultural objects from different cultural contexts. In other words, Lévi-Strauss was not interested in producing a text (i.e., a monograph) on a particular culture, but a text that addressed the understanding of the ‘Universal Man rather than the particular man.

At the Ecole Libre des Hautes Etudes, where Lévi-Strauss had taken up teaching responsibilities, Alexandre Koyré introduced him to the founder of the Prague school of Linguistics, Roman Jacobson. This relationship with Jacobson developed Lévi-Strauss to structuralism. Before that he said that he was a “kind of naïve structuralist, a structuralist without knowing it.” Jacobson introduced him to the methodology of structuralism as it had been formed in the discipline of linguistics. Incidentally, Jacobson also attended Lévi-Strauss’s lectures on kinship and advised him to write about it. Inspired by Jacobson, Lévi-Strauss started writing The Elementary Structures of Kinship in 1943 and finished it in 1947.

This work offered a new approach to the study of kinship systems that has come to be known as ‘alliance theory’ in opposition to what is called ‘descent theory’, which was put forth by British anthropologists (such as A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, Meyer Fortes) and was the dominant theory in kinship studies till then. The emphasis of descent theory was on the transmission of property, office, ritual complex, and rights and obligations across the generations (either in the father’s or mother’s line, or in both the lines), which produced solidarity among the members of the group related by the ties of consanguinity. Lineage was seen as a corporate group, property-holding and organising labour on the lines of blood ties. In this set of ideas, marriage was secondary: since one could not marry one’s sister or daughter, because of the rule of incest taboo, one married a woman from another group. The primary objective of marriage was the procreation of the descent group.

Lévi-Strauss’s alliance theory brought marriage to the centre. The function of marriage was not just procreative. It was far more important, for it led to the building of a string of relations between groups, respectively called the ‘wife givers’ and ‘wife-takers’. In this context, the concept of incest taboo acquires a central place. It is the ‘pre-social’ social fact; if society is a social fact, which explains and accounts for a number of other social facts, the fact that explains society, its emergence and functioning, is incest taboo. For Lévi-Strauss, it is the ‘cornerstone’ of human society. The logical outcome of the prohibition of incest is a system of exchange. It is not only the negative aspect of the rule of incest taboo that needs to be recognised, as was the case with the descent theorists. What was significant to Lévi-Strauss was the positive aspect – it is not only that I do not marry my sister but I also give her in marriage to another man whose sister I then marry. ‘Sister exchange’ creates a ‘federation’ between exchanging groups. Societies are also distinguished with respect to where there is a ‘positive rule of marriage’ (the genealogical specification of the relative to whom one should marry) and where such a rule does not exist. Lévi-Strauss’s work on kinship, the English translation of which was only available in 1969, twenty years after its publication in French, introduced a new approach to the study of kinship and exchange. That marriage is an ‘exchange of women’ where women are a ‘value’ as well as a ‘sign’ – and groups are perpetually linked by cycles of reciprocity, was a fresh way of looking at systems of kinship. Although there were acrimonious debates between the descent and alliance theories (particularly those British anthropologists who subscribed to alliance theory), there was no doubt that Lévi-Strauss’s Elementary Structures acquired the reputation of a work without which no study of kinship and marriage was ever complete. And, even after sixty years of its publication, it is still read with profit. LéviStrauss had planned to write a second volume on complex structures of kinship, where the positive rule of marriage did not exist, but he could never do so, as his attention shifted to the study and analysis of myths.

In 1958 came a collection of his essays, in which he had made use of the methodology of structuralism, called Anthropologie Structural, the English into a ‘friendship of forty years without a break’; it was in the words of LéviStrauss, ‘the beginning of a brotherly friendship.’ This friendship also introduced translation of which under the title Structural Anthropology appeared in 1963. This volume also carried his famous essay on the concept of social structure (which was published in Anthropology Today edited by A.L. Kroeber), where in he had argued that ‘social structure is a model’ rather than an empirical entity and a ‘province of inquiry’ as was the view of Radcliffe-Brown.

In 1962 came his Le Totemism (The Totemism) and La Pensée Sauvage (The Savage Mind). Both these books marked a shift in his interest from the study of kinship to that of religion. In The Totemism, which we shall discuss below as an example of the application of the structural method, he tried to lay the ‘problem of totemism to rest’ once and forever, arguing that totems were modes of classification; they were ‘good to think’ rather than ‘good to eat’. The binary opposition of nature and culture that evolved in his kinship study was further developed here. Rejecting the utilitarian theory of totemism, Lévi-Strauss examined the merits of the second theory of totemism that Radcliffe-Brown had proposed. In The Savage Mind, dedicated to the memory of Merleau-Ponty, Lévi-Strauss’s central point was that the thoughts of the ‘primitive people’ were in no way inferior to those of the ‘Westerners’.

Between 1964 and 1971 were published Lévi-Strauss’s magnum opus, the four volume Mythologiques series. In total, these volumes, running into two thousand pages, analyse 813 myths and their more than one thousand versions. The Raw and the Cooked analyses myths from South America, particularly central and eastern Brazil. The second volume, From Honey to Ashes is also concerned with South America, but deals with myths both from the south and the north. The Origin of Table Manners begins with a myth that is South American, but from further north. The final volume, The Naked Man, is entirely North American. The interesting fact Lévi-Strauss finds is that the “most apparent similarities between myths are found between the regions of the New World that are geographically most distant.” Beginning with the mythology of central Brazil and then moving out to other geographical areas, and then returning to Brazil, Lévi-Strauss realises that “depending upon the case, the myths of neighbouring peoples coincide, partially overlap, answer, or contradict one another.” Thus, the analysis of each myth ‘implied that of others’. Taken as the centre, the myth ‘radiates variants around it.’ It spreads from one neighbour to another in ‘several directions at once.’ His book, The Jealous Potter, was also a part of the series on the analysis of myths. The important fact here is that in spite of his widely acclaimed volumes on mythology, Lévi-Strauss thought that the science of myths was in its infancy. Histoire de Lynx (1991) and Regarder, Écouter, Lire (1993), which discuss his aesthetic and intellectual interests, were his last works.

In one of the courses Lévi-Strauss taught at the Collége de France, he asked questions pertaining to the future of anthropology. Although the traditional societies with which anthropology is concerned are fast changing – some are disappearing as well – anthropologists have done a commendable work of recording as meticulously as possible the life styles and thought patterns of these people. LéviStrauss thought that anthropology was not an ‘endangered science’; however, its character would be transformed in future. Perhaps, it would not be an ‘object of fieldwork’. Anthropologists would become philologists, historians of ideas, and specialists in civilisations, and they would then work with the help of the documents that the earlier observers had prepared. Regarding his own work, Lévi-Strauss said that it ‘signaled a moment in anthropological thought’ and he would be remembered for that.

For Lévi-Strauss, structuralism implies a search for deep, invisible, and innate structures universal to humankind. These unapparent and hidden structures manifest in surface (and conscious) behaviour that varies from one culture to the other. Conscious structures are a ‘misnomer’. Therefore, we have to discover the underlying ‘unconscious’ structures, and how they are transformed into ‘conscious’ structures.

Lévi-Strauss created a stir in anthropology. Some scholars set aside their own line of enquiry for the time being to experiment with his method, whereas the others reacted more critically to his ideas. But nowhere was his impact total and complete he could not create an ‘academic lineage’. His idea of ‘universal structures’ of human mind has been labeled by some as his ‘cosmic ambition’, generalising about human society as a whole. While British anthropologists (especially Edmund Leach, Rodney Needham) in the 1950s and 1960s were impressed with Lévi-Strauss, they were not in agreement with his abstract search for universal patterns. They tended to apply structuralism at a ‘micro’ (or ‘regional’) level. Another example is of the work of Louis Dumont, a student of Marcel Mauss, who in his work Homo Hierarchicus (1967) presented a regional-structural understanding of social hierarchy in India. The approach of applying structural methodology at a micro level is known as ‘neo-structuralism.

The Example of Totemism

Lévi-Strauss’s Totemism, as mentioned earlier, was published in French in 1962. A year later came its English translation, done by an Oxford anthropologist, Rodney Needham, and it carried more than fifty pages of Introduction written by Roger Poole. In appreciation of this book, Poole wrote: In Totemism Lévi-Strauss takes up an old and hoary anthropological problem, and gives it such a radical treatment that when we lay down the book we have to look at the world with new eyes. Before we proceed with Lévi-Strauss’s analysis, let us firstly understand the meaning of totemism.

Totemism refers to an institution, mostly found among the tribal community, where the members of each of its clans consider themselves as having descended from a plant, or animal, or any other animate or inanimate object, for which they have a special feeling of veneration, which leads to the formation of a ritual relationship with that object. The plant, animal, or any other object is called ‘totem’; the word ‘totem’, Lévi-Strauss says (p. 86), is taken from the Ojibwa, an Algonquin language of the region to the north of the Great Lakes of Northern America. The members who share the same totem constitute a ‘totemic group’. People have a special reverential attitude towards their totem – they abstain from killing and/or eating it, or they may sacrifice and eat it on ceremonial occasions; death of the totem may be ritually mourned; grand celebrations take place in some societies for the multiplication of totems; and totems may be approached for showering blessings and granting long term welfare. In other words, the totem becomes the centre of beliefs and ritual action.

Lévi-Strauss does not believe in the ‘reality’ of totemism. He says that totemism was ‘invented’ and became one of the most favourite anthropological subjects to be investigated with an aim to find its origins and varieties, with the Victorian scholars in the second half of the nineteenth century. By contrast, Lévi-Strauss’s study is not of totemism; it is of totemic phenomena. In other words, it is an ‘adjectival study’, and not a ‘substantive study’, which means that it is a ‘study of the phenomena that happen to be totemic’ rather than ‘what is contained in or what is the substance of totemism’. At his command, Lévi-Strauss has the same data that were available to his predecessors, but the question he asks is entirely new. He does not ask the same question that had been repeatedly asked earlier by several scholars, vis. ‘What is totemism?’ His question is ‘How are totemic phenomena arranged?’ The move from ‘what’ to ‘how’ was radical at that time (during the 1960s) ; and Lévi-Strauss’s interpretation of totemism was a distinct break with the earlier analyses of totemism (whether they were evolutionary, or diffusionistic, or functional). It is because of this distinctiveness that Poole writes that with Lévi-Strauss, “the ‘problem’ of totemism has been laid to rest once and for all.

Lévi-Strauss offers a critique of the explanations that had been (and were) in vogue at that time. Firstly, he rejects the thesis that the members of the American school (Franz Boas, Robert Lowie, A.L. Kroeber) put forth, according to which the totemic phenomena are not a reality sui generic. In other words, totemism does not have its own existence and laws; rather it is a product of the general tendency among the ‘primitives’ to identify individuals and social groups with animal and plant worlds. Lévi-Strauss finds this explanation highly simplistic. He also criticises the functional views of totemism; for instance, Durkheim’s explanation that totemism binds people in a ‘moral community’ called the church, or Malinowski’s idea that the Trobrianders have totems because they are of utilitarian value, for they provide food to people. Malinowski’s explanation (which Lévi-Strauss sums up in words like ‘totems are good to eat’) lacks universality, since there are societies that have totems of non-utilitarian value, and it would be difficult to find the needs that the totem fulfils. Durkheim’s thesis of religion as promoting social solidarity may be applicable in societies each with a single religion, but not societies with religious pluralism. Moreover, the functional theory is concerned with the contribution an institution makes towards the maintenance of the whole society, rather than how it is arranged. In other words, the functional theory of totemism deals with the contribution the beliefs and practices of totemism make to the maintenance and well-being of society rather than what is the structure of totemism, and how it is a product of human mind.

The Method

Lévi-Strauss’s Totemism is principally an exercise in methodology. He does not look for the unity of the phenomenon of totemism; rather, he breaks it down into various visual and intellectual codes. He does not intend to explain totemism, rather he deciphers it Lévi-Strauss summarises his methodological programme, which is as follows:

1) Define the phenomenon under study as a relation between two or more terms, real or supposed

2) construct a table of possible permutations between these terms

3) take this table as the general object of analysis which, at this level only, can yield necessary connections, the empirical phenomenon considered at the beginning being only one possible combination among others, the complete system of which must be reconstructed beforehand. We may give here a simple example to understand this from the realm of kinship. Descent, for instance, can be traced from the father or the mother. Let us call the descent traced from the father ‘p’, and the mother ‘q’. Now, let us assign them their respective values: if the side (whether the father’s or the mother’s) is recognised, we denote it by 1, and if it is not recognised, it is denoted as . Now, we can construct the table of the possible permutations: where (1) p is 1, and q is 0; (2) p is 0, and q is 1; (3) p is 1, and q is 1; and (4) p is 0 and q is 0. The first permutation yields the patrilineal society, the second, matrilineal, the third, bilineal, and the last possibility does not exist empirically.

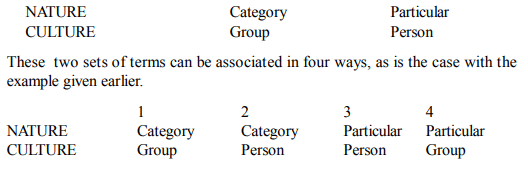

Let us now move to how Lévi-Strauss applies this to totemism. He says that totemism covers relations between things falling in two series – one natural (animals, plants) and the other cultural (persons, clans). For Lévi-Strauss, the ‘problem’ of totemism arises when two separate chains of experience (one of nature and the other of culture) are confused. Human beings identify themselves with nature in a myriad of ways, and the other thing is that they describe their social groups by names drawn from the world of animals and plants. These two experiences are different, but totemism results when there is any kind of overlap between these orders. Further, Lévi-Strauss writes: ‘The natural series comprises on the one hand categories, on the other particulars; the cultural series comprises groups and persons.’ He chooses these terms rather arbitrarily to distinguish, in each series, two modes of existence – collective and individual and also, to keep these series distinct. Lévi-Strauss says that any terms could be used provided they are distinct.

Totemism thus establishes a relationship between human beings (culture) and nature, and, as shown above, this relationship can be divided into four types, and we can find empirical examples of each one of them.

Lévi-Strauss says that the example of the first is the Australian totemism (‘sex totems’ and ‘social totems’) that postulates a relationship between a natural category and a cultural group. The example of the second is the ‘individual’ totemism of the North American Indians. Among them, an individual reconciles himself with a natural category. For an example of the third combination, Lévi-Strauss takes the case of the Mota (in the Banks Islands) where a child is thought to be the ‘incarnation of an animal or plant found or eaten by the mother when she first became aware that she was pregnant’ or what has come to be known as ‘incarnational totemism’. Another example of this category may come from certain tribes of the Algonquin group, who believe that a special relation is established between the newborn child and whichever animal is seen to approach the family cabin. The fourth combination (group-particular combination) may be exemplified with cases from tribes of Polynesia and Africa, where certain animals (such as garden lisards in New Zealand, sacred crocodiles and lions and leopards in Africa) are protected and venerated (the sacred animal totemism).

The four combinations are equivalent. It is because they result from the same operation (i.e., the permutation of the elements that comprise a phenomenon). But, in the anthropological literature that Lévi-Strauss examines, it is only the first two that have been included in the domain of totemism, while the other two have only been related to totemism in an indirect way. Some authors have not considered the last two variants of totemism in their discussion. Here, Lévi-Strauss observes that the ‘problem of totemism’ (or what is called the ‘totemic illusion’) results from the ‘distortion of a semantic field to which belong phenomena of the same type.’ The outcome of this is that certain aspects (or the first and second types of totemic phenomena) have been singled out at the expense of others (the third and fourth types), which gives an impression of ‘originality’ and ‘strangeness’ that they do not in reality possess.

The Analysis

The fourth chapter of Lévi-Strauss’s Totemism, titled ‘Towards the Intellect’, presents the work of Raymond Firth, Mayer Fortes, Edward Evans-Pritchard, and the second theory of totemism (of 1951) that Alfred Radcliffe-Brown gave, as containing the germs of a correct interpretation of totemic phenomenon making possible a fully adequate explanation of its content and form. Radcliffe-Brown’s first theory of totemism was utilitarian and culture-specific, quite like Malinowski’s theory. By comparison, Firth and Fortes do not succumb to an arbitrary explanation or to any factitious evidence. Both of them think that the relationship between totemic systems and natural species is based on a perception of resemblance between them. In Fortes’s work on the Tallensi, animals and ancestors resemble each other. Animals are apt symbols for the livingness of ancestors. Fortes shows that among the Tallensi, animals symbolise the potential aggressiveness of ancestors.

Lévi-Strauss applauds the attempt of Firth and Fortes, for they move from a point of view centred on subjective utility (the utilitarian hypothesis) to one of objective analogy. But Lévi-Strauss goes further than this: he says ‘it is not the resemblances, but the differences, which resemble each other’. In totemism, the resemblance is between the two systems of differences. Let us understand its meaning with the help of an example: the relationship between two clans is like the relationship between two animals, or two birds, or an animal and a bird. It is the difference between the two series that resembles each other.

Undoubtedly, Firth and Fortes make a good beginning in interpreting totemism. But we have to move from external analogy (the external resemblance) to internal homology (the identity at the internal level). For Lévi-Strauss, it is Evans-Pritchard’s analysis of Nuer religion that allows us to move from the external resemblance to internal homology. Among the Nuer, the twins are regarded as ‘birds’, not because they are confused with birds or look like them. It is because, the twins, in relation to other persons, are ‘persons of the above’ in relation to ‘persons from below’. And, with respect to birds, they are ‘birds of below’ in relation to ‘birds from above’. The relationship between twins and other men is like the relationship that is deemed to exist between the ‘birds of below’ and the ‘birds of above’. It is a good example of the ‘differences which resemble each other’ in the ‘two systems of differences’. If the statement – or the code twins are birds’ directs us to look for some external image, then we are surely bound to be led astray. But if we look into the internal homology in the Nuer system, then we will be closer to the understanding of the code.

At this level, Lévi-Strauss introduces the second theory of Radcliffe-Brown that has taken a decisive and innovatory step in interpreting totemism. Instead of asking, ‘Why all these birds?’, Radcliffe-Brown asks: ‘Why particularly eaglehawk and crow, and other pairs?’ Lévi-Strauss considers this question as marking the beginning of a genuine structural analysis. In fact, Radcliffe-Brown observes in this analysis of totemism that the kind of structure with which we are concerned is the ‘union of opposites.’

Evans-Pritchard and Radcliffe-Brown, thus, recognise two principles of interpretation which Lévi-Strauss deems fundamental. In his analysis of Nuer religion, Evans-Pritchard shows that the basis of totemic phenomena lies in the interrelation of natural species with social groupings according to the logically conceived processes of metaphor and analogy. In his second theory, Radcliffe-Brown realises the necessity of an explanation which illuminates the principle governing the selection and association of specific pairs of species and types used in classification. These two ideas, Lévi-Strauss thinks, help in the reintegration of content with form, and it is from them that he begins.

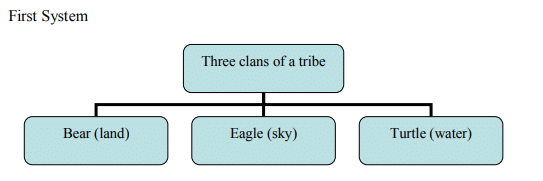

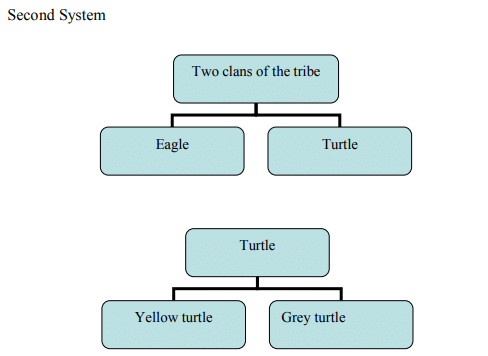

Totemism, for Lévi-Strauss, is a mode of classification. Totemic classifications are regarded as a ‘means of thinking’ governed by less rigid conditions than what we find in the case of language, and these conditions are satisfied fairly easily, even when some events may be adverse. The functions that totemism fulfill are cognitive and intellectual: ‘totems are not good to eat, they are good to think’. The problem of totemism disappears when we realise that all humans, at all points of time, are concerned with one or the other mode of classification, and all classifications operate using mechanisms of differentiation, opposition, and substitution. Totemic phenomena form one aspect of a ‘general classificatory ideology’. If it is so, then the problem of totemism, in terms of something distinct that demands an explanation, disappears. Jenkins (1979: 101) writes: ‘Totemism becomes analytically dissolved and forms one expression of a general ideological mode of classification.’ But it does not imply that totemism is static. Although the nature of the conditions under which totemism functions have not been stated clearly, it is clear from the examples that Lévi-Strauss has given that totemism is able to adapt to changes. To illustrate this, a hypothetical example may be taken up. Suppose a society has three clans totemically associated respectively with bear (land), eagle (sky), and turtle (water). Because of demographic changes, the bear clan becomes extinct, but the turtle clan enlarges, and in course of time, splits into two parts. The society faces this change in two ways. First, the same totemic association might be preserved in a damaged form so that the only classificatory symbolic correlation is now between sky (eagle) and water (turtle). Second, a new correlation may be generated by using the defining characteristics of the species turtle to distinguish between two clans still identified with it. This becomes the basis for the formation of a new symbolic opposition. If, for example, colour is used, yellow and grey turtles may become totemic associations. Yellow and grey may be regarded as expressive of the basic distinction between day and night perhaps. A second system of the same formal type as the first is easily formed through the process of differentiation and opposition (see diagrams of the first and second systems below).

As is clear, the opposition between sky (eagle) and water (turtle) is split and a new opposition is created by the contrast of day (yellow) and night (grey). In this way, the problems caused by demographic imbalances (i.e., extinction of a clan or the enlargement of the other) are structurally resolved, and the system continues.

Summary of the Study of Totemism

To sum up, totemic phenomena are nothing but modes of classification. They provide tribal communities with consciously or unconsciously held concepts which guide their social actions. Food taboos, economic exchanges and kinship relations can be conceptualised and organised using schemes which are comparable to the totemic homology between natural species and social characteristics. Lévi-Strauss (1962) also extends this analysis to understand the relation between totemism and caste system. Totemism is a relationship between man and nature. Similarities and differences between natural species are used to understand the similarities and differences between human beings. Totemism, which for people is a type of religion, is a way of understanding similarities and differences between man and nature. That is the reason why Poole says that with Lévi-Strauss, the problem of totemism has been laid to rest once and for ever.

If we talk about ‘totemism’ any more, it will be in ignorance of Lévi-Strauss or in spite of him.

Final Comments

This lesson has introduced you to the basic tenets of structuralism. We have principally focused on the work of Claude Levi-Strauss, illustrating it with the example of totemism, since he is regarded as the main exponent of this method. As was stated earlier, Levi-Strauss worked on kinship, totemism, and myths, and was interested in discovering the underlying structures, which he thought were universal. He was interested in knowing how human mind worked.

That was where his contemporaries and scholars sympathetic to his approach differed with him. They thought that Levi-Strauss was too ambitious in his approach. The structures he was looking for were more his creation than those that emerged from the facts of actual existence. These scholars applied structuralism to the understanding of local, regional systems, and this approach came to be known as ‘neo-structuralism’. One of its proponents was Edmund Leach, the British anthropologist.

Leach was certainly critical of the structural-functional ideas, but one thing he learnt from this was researching people’s actual ideas, rather than discovering the so-called universal mental structures. In his work, Leach made a distinction between ‘jural rules’ and ‘statistical norms’. Whilst the first referred to the rules as these were in the minds of people, the second were the rules in actual practice.

Structuralism is a-historical, which means that the structures it discovers cut across the time dimension. These are applicable to all societies at all points of time. This is one proposition of structuralism that has invited a number of criticisms. A good method is one which takes care of both the dimensions of time and space.

|

209 videos|299 docs

|