Kinship, Caste and Class Class 12 History

Introduction

By studying ancient texts like the Mahabharata, Dharmasutras, and Buddhist writings, historians understand how family ties, caste, and social class shaped societal rules and behaviours. These factors set up the social order and influenced everyday interactions, marriages, and how wealth and power were passed down.

The Critical Edition of the Mahabharata

The Mahabharata's Composition

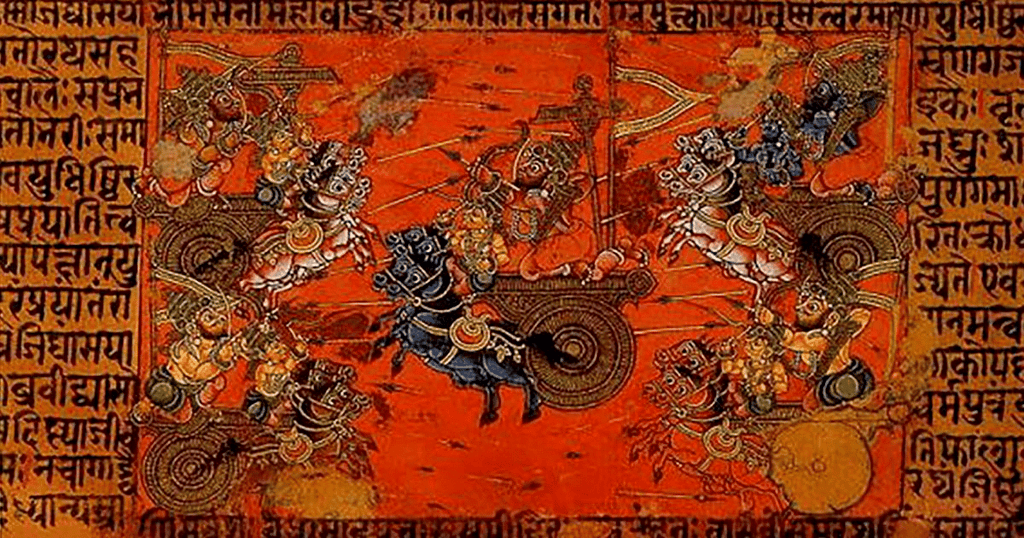

- The Mahabharata, a major ancient text from India, was written over about 1,000 years, starting around 500 BCE.

- It tells the story of two groups of rival cousins, the Kauravas and Pandavas, and includes rules for how different social groups should behave.

- The text shows how early and later societies were shaped through conversations between major traditions and local beliefs.

- Originally, poet-warriors who travelled with Kshatriya fighters created the story, singing about their victories.

- From around the fifth century BCE, Brahmanas started writing it down, reflecting the shift from tribal chiefdoms to organised kingdoms.

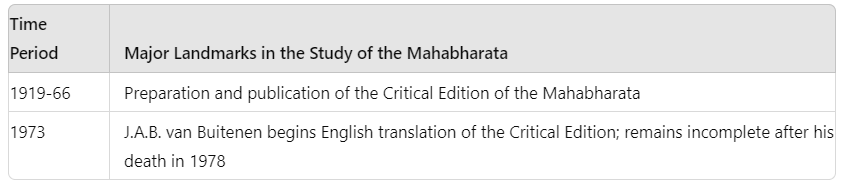

The Critical Edition Project

- In 1919, V.S. Sukthankar started a project to create a detailed version of the Mahabharata.

- The team gathered Sanskrit manuscripts from different parts of India, written in various scripts, to compare verses and note regional differences.

- The project took 47 years and produced a 13,000-page critical edition.

- This edition showed both shared elements and notable regional variations, revealing how the text evolved across India.

- Footnotes and appendices highlight how major traditions and local customs interacted.

Kinship and Marriage: Many Rules and Varied Practices

Finding about the Families- In early societies, kinship or family structures varied widely across regions and groups, shaping social rules and daily life.

- Families often shared resources, lived together, and performed rituals as a group, but what counted as "family" differed.

- For example, some communities saw cousins as close relatives, while others did not.

- Historians study these family ties to understand how people thought and behaved, as these ideas likely influenced social actions.

- It's easier to find information about elite families, but figuring out the family lives of ordinary people is much harder.

The Ideal of Patriliny

Patriliny is a system where family lineage and inheritance are traced through the male line, from father to son, grandson, and beyond. It emphasizes the role of men in passing down family names, property, or status.

- Matriliny is the term used when descent is traced through the mother.

- The concern with patriliny was not unique to ruling families. It is evident in mantras in ritual texts such as the Rigveda.

- It is possible that these attitudes were shared by wealthy men and those who claimed high status, including Brahmanas.

- Mahabharata describes a feud over land and power between two groups of cousins, the Kauravas and the Pandavas, who belonged to a single ruling family, that of the Kurus, a lineage dominating one of the janapadas. At the end, the Pandavas emerged victorious. After that, patrilineal succession was proclaimed.

- While patriliny had existed prior to the composition of the epic, the central story of the Mahabharata reinforced the idea that it was valuable. Under patriliny, sons could claim the resources (including the throne in the case of kings) of their fathers when the latter died.

- Most ruling dynasties (c. sixth century BCE onwards) claimed to follow this system, with variations in the case of no son.

- The concern with patriliny was not unique to ruling families. It is evident in mantras in ritual texts such as the Rigveda. It is possible that these attitudes were shared by wealthy men and those who claimed high status, including Brahmanas.

Rules of Marriage

- Marriage rules helped keep society organised and built family alliances.

- Marrying outside one’s family group was common, especially for high-status families, to create ties and avoid marrying close relatives.

- Young girls from these families were closely watched to ensure they married the “right” person at the “right” time, with kanyadana (gifting a daughter in marriage) seen as a key duty for fathers.

- Different marriage types, like arranged, love-based, or even capture-based marriages, existed, showing varied customs.

- The Manusmriti, an important legal text, listed eight marriage types, labelling some as “good” and others as “bad,” reflecting changing social values.

- These included giving a daughter to a scholar, love marriages, or marriages involving wealth, showing different priorities in society.

The Gotra of Women

- Around 1000 BCE, Brahmanical tradition classified people into gotras, named after ancient Vedic seers, to organise social groups.

- Women typically took their husband’s gotra after marriage, following patrilineal customs.

- However, in the Satavahana dynasty, some women kept their father’s gotra, showing endogamy (marrying within the same kin group), which strengthened community ties and reflected regional differences in family practices.

- Some Satavahana rulers practised polygyny, having multiple wives.

- By studying gotra-based names in inscriptions, historians can track family connections and marriages, revealing how closely people followed Brahmanical rules.

Were Mothers Important?

- Satavahana rulers were identified through metronymics (names derived from the mother), suggesting the importance of mothers in naming conventions.

- However, succession to the throne was generally patrilineal, indicating a complex interplay between matrilineal and patrilineal influences.

- The use of metronymics highlights the significance of mothers in early Indian society, despite the dominance of patrilineal succession.

- Historical records show that some women retained their father's gotra, challenging Brahmanical norms and reflecting alternative practices.

- The examination of metronymics and succession practices provides insights into the roles and status of women in early Indian society.

Social Differences: Within and Beyond the Framework of Caste

The "Right" Occupation

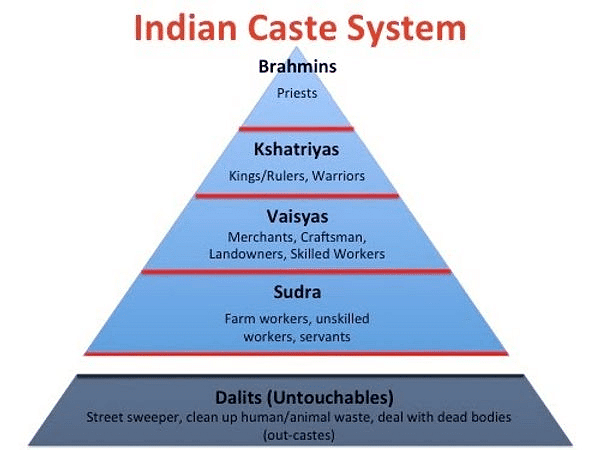

- The Dharmasutras and Dharmashastras prescribed ideal occupations for the four varnas: Brahmanas, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras.

- Brahmanas were to study and teach the Vedas, perform sacrifices, and give and receive gifts, emphasising their role in religious and educational activities.

- Kshatriyas were to engage in warfare, protect people, and administer justice, reflecting their role as rulers and warriors.

- Vaishyas were to engage in agriculture, pastoralism, and trade, highlighting their role in economic activities.

- Shudras were assigned the occupation of servitude, serving the three higher varnas, reflecting their lower status in the social hierarchy.

- Brahmanas used various strategies to enforce these norms, asserting divine origin, advising kings, and persuading people that status was determined by birth.

Non-Kshatriya Kings

- Although Brahmanical texts claimed that only Kshatriyas could be kings, historical evidence shows that many rulers, including the Mauryas and Shakas, did not fit this ideal.

- The Mauryas, who ruled a large empire, were debated to be of non-Kshatriya origin, with Buddhist texts suggesting they were Kshatriyas, while Brahmanical texts described them as of "low" origin.

- The Shungas and Kanvas, successors of the Mauryas, were Brahmanas, challenging the notion that only Kshatriyas could be rulers.

- Political power often depended on one's ability to muster support and resources, rather than strict adherence to the varna system.

- The case of Rudradaman, a Shaka ruler who rebuilt the Sudarshana lake, shows that powerful mlechchhas (outsiders) were familiar with Sanskritic traditions and held significant power.

Jatis and Social Mobility

- Beyond the four main varnas, many jatis (sub-castes) formed, often tied to specific jobs, allowing people to move up socially within their professions.

- Jatis were sometimes grouped into guilds (shrenis), which organised economic activities together.

- The Mandasor inscription (around the fifth century CE) describes a guild of silk weavers who moved to a new area, showing how they were organised and their social roles.

- It reveals that guild members shared more than just a job, working together on projects like building a temple.

- When Brahmanical authorities met groups that didn’t fit the four varnas, they assigned them to jatis, showing how flexible and adaptable social categories were.

Beyond the Four Varnas: Integration

- Populations whose social practices were not influenced by Brahmanical ideas, such as forest-dwellers and nomadic pastoralists, were often described as odd or uncivilised.

- Brahmanical texts often viewed certain groups as outsiders, calling them mlechchhas and treating them with suspicion, showing a rigid and exclusive social outlook.

- Still, stories in the Mahabharata reveal that settled communities and these marginalised groups shared ideas and beliefs.

- For example, the tale of Ekalavya, a young Nishada from a hunting community, shows the clash between Brahmanical rules and the abilities of marginalised groups.

- Historians explore these interactions to understand how early Indian society blended diverse groups and evolved dynamically.

Beyond the four varnas: Subordination and conflict

- The Brahmanical social order also included categories such as chandalas (untouchables), who were assigned degrading tasks and faced severe discrimination.

- The Manusmriti laid down the duties and restrictions for chandalas, such as living outside the village, using discarded utensils, and wearing clothes of the dead.

- Chandalas were expected to dispose of bodies and serve as executioners, reflecting their marginalisation and subordination.

- Historical texts like the Chinese pilgrim Fa Xian's accounts provide additional insights into the lives of untouchables and their social exclusion.

- Examining non-Brahmanical texts and inscriptions reveals that social realities were often more complex, with some individuals and groups challenging their prescribed roles.

Beyond Birth: Resources and Status

Gendered Access to Property

- Gender significantly influenced access to resources, with men inheriting and controlling wealth while women's access was limited.

- The Manusmriti allowed women to retain gifts received at marriage (stridhana or a woman's wealth), but broader property rights were restricted.

- Wealthy women like the Vakataka queen Prabhavati Gupta had some access to resources, but overall, land, cattle, and money were generally controlled by men.

- Social differences between men and women were sharpened due to the disparities in access to resources, reinforcing gender inequalities.

- The story of Draupadi in the Mahabharata, where she was staked and lost in a game of dice, illustrates the limited agency and property rights of women.

Varna and Access to Property

- According to Brahmanical texts, another criterion for regulating access to wealth was varna, with different occupations and privileges assigned to each varna.

- Brahmanas and Kshatriyas were typically depicted as wealthy, with priests and kings enjoying significant economic resources.

- Other traditions, such as Buddhism, critiqued the rigid varna order and emphasised ethical conduct and merit over birth-based status.

- The Buddhist text Majjhima Nikaya highlights the idea that wealth, not birth, determines social relationships, challenging Brahmanical views.

- This critique of the varna system reflects the dynamic and contested nature of social hierarchies in early Indian society.

An Alternative Social Scenario: Sharing Wealth

- In certain regions, like ancient Tamilakam, social status was also linked to generosity and the sharing of wealth.

- Chiefs were expected to share their wealth with bards and poets, reflecting a cultural value that esteemed generosity over mere accumulation.

- Poems from the Tamil Sangam literature illuminate social and economic relationships, suggesting that those who controlled resources were expected to share them.

- The story of a poor but generous chief from the Puranaruru, a Tamil Sangam anthology, highlights the importance of generosity in social interactions.

- This alternative social scenario emphasises the role of generosity and communal sharing in maintaining social cohesion and status.

Explaining Social Differences: A Social Contract

- Buddhist texts offered alternative views on social inequality and the institutions required to regulate social conflict.

- A myth from the Sutta Pitaka suggests that originally human beings lived in an idyllic state, taking only what they needed from nature.

- As greed, vindictiveness, and deceit increased, human beings selected a leader to maintain order, known as the mahasammata (the great elect).

- This myth implies that kingship and social order were based on human choice and mutual agreement, with taxes as payment for services rendered by the king.

- The recognition of human agency in creating social systems suggests that these systems could be changed, offering a critique of the static and divine nature of the Brahmanical social order.

Handling Texts: Historians and the Mahabharata

Language and Content

- The Mahabharata is written in simpler Sanskrit, suggesting it was widely understood compared to the more complex language of the Vedas or prashastis.

- Historians classify the content into narrative (stories) and didactic (prescriptive norms) sections, recognising that these divisions are not watertight.

- The text is described as an itihasa (history), though its literal truth is debated, with some historians suggesting it preserves the memory of an actual conflict among kinfolk.

- The narrative sections include dramatic and moving stories, while the didactic sections likely added later, provide social messages and norms.

- The interplay between narrative and didactic elements highlights the evolving nature of the text and its reflections of social realities.

Author(s) and Dates

- The original story was likely composed by charioteer-bards known as sutas, who celebrated the victories and achievements of Kshatriya warriors.

- From the fifth century BCE, Brahmanas began to commit the story to writing, reflecting the transition from chiefdoms to kingdoms.

- The Mahabharata evolved over centuries, with significant additions during periods when the worship of Vishnu gained prominence, and Krishna became identified with Vishnu.

- The text is traditionally attributed to the sage Vyasa, who is said to have compiled the final version, which grew from fewer than 10,000 verses to about 100,000 verses.

- The composition and compilation of the Mahabharata reflect the dynamic and contested nature of social and religious changes in early Indian society.

The Search for Convergence

- Archaeological excavations, like those at Hastinapura by B.B. Lal in 1951-52, provide some evidence supporting the epic's descriptions.

- Lal's findings, such as mud and burnt-brick houses and soakage jars, suggest a settlement that might correspond to the epic's Hastinapura.

- The descriptions of the city in the Mahabharata, such as grand palaces and urban infrastructure, might reflect later additions when urban centres flourished.

- The complex nature of the text and its creative narrative pose challenges in correlating it directly with archaeological evidence.

- Historians use these findings to explore the possible historical context of the Mahabharata, while acknowledging the blend of history and poetic imagination in the text.

Draupadi's Marriage:

- One of the most challenging episodes in the Mahabharata is Draupadi's marriage to the Pandavas, an instance of polyandry that is central to the narrative.

- The text offers multiple explanations for this practice, such as Draupadi's prayers to Shiva, and the seer Vyasa's interpretations, reflecting the contested nature of polyandry.

- The practice of polyandry may have been prevalent among ruling elites during times of crisis or shortage of women, but it gradually fell into disfavour among Brahmanas.

- The episode's multiple explanations highlight the text's creative narrative requirements and its engagement with different social practices.

- Historians suggest that while polyandry was unusual, its inclusion in the epic indicates the diversity and fluidity of marriage practices in early Indian society.

A Dynamic Text

- The growth of the Mahabharata did not stop with the Sanskrit version.

- Over the centuries, versions of the epic were written in a variety of languages.

- This growth was part of an ongoing process of dialogue between people, communities, and those who wrote the texts.

- Several stories that originated in specific regions or circulated among certain people found their way into the epic.

- The central story of the epic was often retold in different ways.

- Episodes from the Mahabharata were depicted in sculpture and painting.

- The epic provided themes for a wide range of performing arts, including plays, dance, and other kinds of narrations.

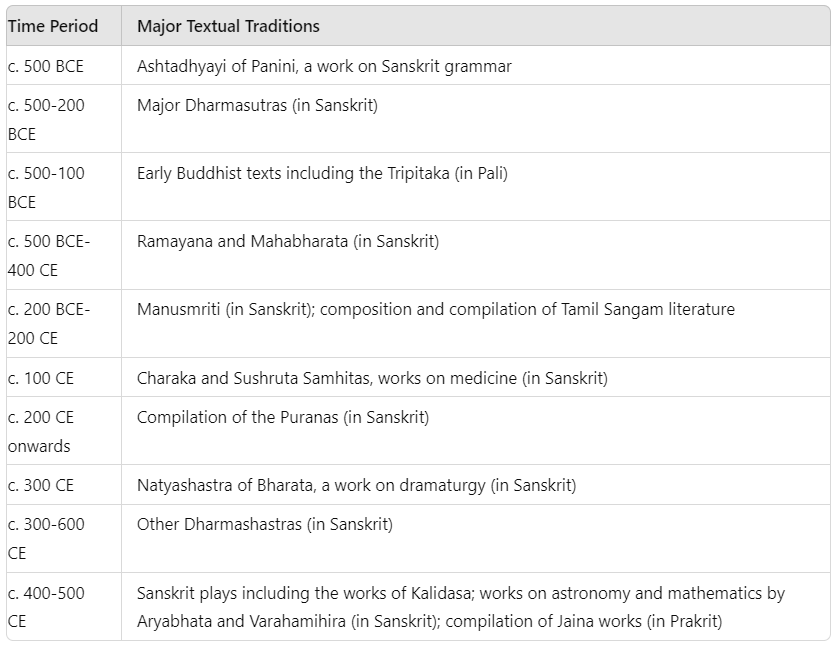

Timeline

Major Textual Traditions

Major Landmarks in the Study of the Mahabharata

Summary

- Many rules and different practices were followed by the people.

- Very often, families were part of larger networks of people we define as relatives. Blood relations can be defined in many different ways.

- Mausmriti is considered the most important Dharma Sutra and Dharmashastra. It was compiled between 200 BCE and 200 CE. These laid down rules governing social life.

- During the Mahabharata age, gotras were considered very important by the higher varna of society.

- Social differences prevailed, and integration took place within the framework of the caste system.

- According to the sutras, only Kshatriyas could be a king.

- The original version of the Mahabharata is in Sanskrit.

- It contains vivid descriptions of battles, forests, palaces and settlements.

|

30 videos|274 docs|25 tests

|

FAQs on Kinship, Caste and Class Class 12 History

| 1. What is the significance of the Critical Edition of the Mahabharata in understanding ancient Indian society? |  |

| 2. How do kinship and marriage practices in ancient India reflect social norms and values? |  |

| 3. How do social differences manifest within and beyond the framework of caste in ancient Indian society? |  |

| 4. What role did resources and status play in determining an individual's social position in ancient Indian society? |  |

| 5. How did historians handle texts like the Mahabharata to understand and interpret social structures and practices in ancient India? |  |