Bhakti- Sufi Traditions Class 12 History

Introduction

India’s religious history is like a mix of many different beliefs and traditions. Over time, these beliefs have mixed, clashed, and changed. From the spread of Brahmanical ideas through old stories to the growth of groups like the Jagannatha in Puri, big changes happened between the eighth and eighteenth centuries. Conflicts between different groups showed how lively religious discussions were, shaping how people lived and thought about spirituality.

A Mosaic of Religious Beliefs and Practices

The Integration of Cults

- During this period, there was a deliberate effort to spread Brahmanical ideas. This was manifested through the composition, compilation, and preservation of Puranic texts. What makes these texts distinct is their use of simple Sanskrit verse, making them accessible to segments of society traditionally excluded from Vedic learning, such as women and Shudras.

- Simultaneously, there was a dynamic process where Brahmanas actively embraced and reinterpreted the beliefs and practices of various social categories. This interaction between the "great" Sanskritic Puranic traditions and "little" traditions across the subcontinent shaped the evolving religious landscape.

Subhadra, Balabhadra and Jagannath

Subhadra, Balabhadra and Jagannath - Illustrating this integration is the case of Puri in Orissa. By the twelfth century, the principal deity in Puri came to be recognized as Jagannatha, a form of Vishnu. The interesting aspect here is the transformation of a local deity, traditionally represented by a wooden image crafted by tribal specialists, into a recognized form of Vishnu.

- A similar process of integration can be observed within goddess cults. Local deities, often represented by simple stones smeared with ochre, were incorporated into the broader Puranic framework. This was achieved by identifying them as consorts or wives of principal male deities like Lakshmi or Parvati.

Difference and Conflict

- Tantric practices, associated with goddess worship, emerged as notable and inclusive, transcending traditional caste and class boundaries.

- Over the next millennium, diverse beliefs and practices were classified under 'Hindu', despite differences between Vedic and Puranic traditions, with Vedic deities becoming marginalized.

- Conflicts arose as devotees emphasized the supremacy of Vishnu or Shiva, leading to tensions within the religious landscape and with other traditions like Buddhism and Jainism.

- Devotional worship, with a history spanning nearly a thousand years, ranged from routine temple worship to intense, ecstatic adoration, where devotees often entered trance-like states.

- Singing and chanting of devotional compositions played a pivotal role in Vaishnava and Shaiva sects, becoming an integral part of religious practices and enhancing emotional and spiritual engagement.

Poems of Prayer Early Traditions of Bhakti

Bhakti movements fostered poet-saints who became central figures, gathering communities of devotees through their teachings and compositions.

These movements challenged Brahmanical norms by including women and lower castes, providing avenues for spiritual liberation beyond traditional restrictions.

Bhakti traditions demonstrated significant diversity, encompassing various practices and beliefs that ranged from personalized devotion to specific deities (saguna bhakti) to abstract worship of the formless divine (nirguna bhakti).

Saguna bhakti focused on anthropomorphic deities like Shiva, Vishnu, and forms of the goddess, emphasizing their divine attributes.

Nirguna bhakti involved devotion to an abstract, attributeless form of the divine, transcending anthropomorphic representations and emphasizing the unity of all existence under a singular divine principle.

The Alvars and Nayanars of Tamil Nadu

- The earliest bhakti movements (around the sixth century) were led by the Alvars (devotees of Vishnu) and Nayanars (devotees of Shiva).

- They traveled, singing hymns in Tamil praising their gods. The Alvars and Nayanars identified certain shrines as sacred abodes of their deities, and large temples were often built at these sites, turning them into centres of pilgrimage.

- Singing the compositions of these poet-saints became part of temple rituals, along with worship of the saints’ images.

Attitudes towards Caste

- Historians suggest that the Alvars and Nayanars initiated a movement against the caste system and the dominance of Brahmanas, possibly attempting to reform the system. Bhaktas, followers of these movements, came from diverse social backgrounds, including Brahmanas, artisans, cultivators, and even castes considered "untouchable."

- The significance of the Alvars and Nayanars was underscored by claims that their compositions were as vital as the Vedas. For example, the Nalayira Divyaprabandham, a major anthology of Alvars' compositions, was often described as the Tamil Veda, emphasizing its importance comparable to the four Vedas cherished by Brahmanas.

Women Devotees

- An exceptional aspect of these traditions was the active participation of women. Compositions of women Alvars, such as Andal, who saw herself as the beloved of Vishnu, and Karaikkal Ammaiyar, a devotee of Shiva, were widely sung.

- These women, while renouncing social obligations, didn't adopt an alternative order or become nuns, challenging patriarchal norms.

Relations with the State

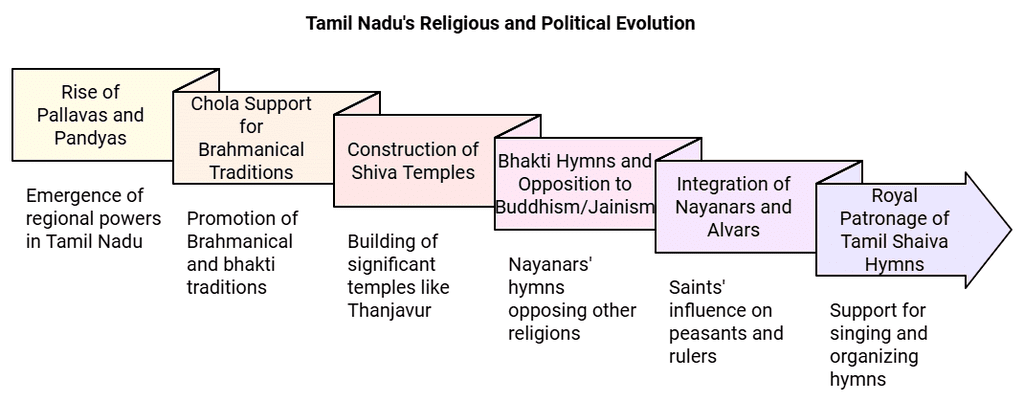

- During this period, the Tamil region witnessed the rise of states, including those of the Pallavas and Pandyas, from the sixth to the ninth centuries CE. The powerful Chola rulers from the ninth to thirteenth centuries CE supported Brahmanical and bhakti traditions, making land grants and constructing temples for Vishnu and Shiva.

- Notably, Tamil bhakti hymns often expressed opposition to Buddhism and Jainism, particularly in the compositions of the Nayanars. Some historians attribute this hostility to competition for royal patronage among members of different religious traditions.

- The Chola rulers actively supported Brahmanical and bhakti traditions, constructing magnificent Shiva temples, including those at Chidambaram, Thanjavur, and Gangaikondacholapuram. The visions of the Nayanars inspired artists, leading to the creation of spectacular representations of Shiva in bronze sculptures.

- Both Nayanars and Alvars were revered by Vellala peasants, and rulers sought their support. Chola kings, in particular, attempted to claim divine support by building splendid temples adorned with stone and metal sculptures, recreating the visions of these popular saints who sang in the language of the people. The rulers introduced the singing of Tamil Shaiva hymns in temples under royal patronage, organizing them into a text known as Tevaram.

- Inscriptional evidence around 945 CE suggests that Chola ruler Parantaka I consecrated metal images of Appar, Sambandar, and Sundarar in a Shiva temple. These images were carried in processions during the festivals of these saints, further emphasizing the integration of bhakti traditions with the state and popular religious practices.

The Virashaiva Tradition in Karnataka

- In the 12th century, Basavanna, a Brahmana minister under a Kalachuri ruler, founded the Virashaiva movement in Karnataka.

- His followers, known as Virashaivas or Lingayats, worship Shiva as the linga and remain a significant community in Karnataka today.

- Lingayats wear a small linga in a silver case and revere wandering monks known as jangama.

- After death, Lingayats believe devotees unite with Shiva and do not perform cremation rituals but ceremonially bury their dead.

- The movement challenged Brahmanical norms such as caste distinctions, ritual pollution, and the concept of rebirth.

- Lingayats also supported practices like post-puberty marriage and widow remarriage, contrary to Dharmashastras.

- The Virashaiva tradition is primarily known through vachanas, profound sayings composed in Kannada by its adherents, offering insights into their beliefs and teachings.

Religious Ferment in North India

- During this period in North India, deities like Vishnu and Shiva were worshipped in temples patronized by rulers. However, there's no evidence of movements similar to the Alvars and Nayanars until the 14th century.

- Rajput states emerged in North India, with Brahmanas holding influential positions in secular and ritual roles, largely unchallenged.

- Meanwhile, alternative religious leaders such as Naths, Jogis, and Siddhas, often from artisanal backgrounds like weavers, gained prominence. They questioned Vedic authority and spoke languages of ordinary people.

- The arrival of the Turks and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century weakened Rajput states and Brahmanical influence, paving the way for significant cultural and religious changes.

- The Sufis, arriving during this period, played a crucial role in these transformations, marking a shift in religious dynamics in North India.

New Strands in the Fabric Islamic Traditions

- Arab merchants established trade links along the western coast of the Indian subcontinent from the early centuries CE, introducing Islam to the region.

- Communities from Central Asia settled in north-western India during the same period, contributing to cultural diversity and interactions.

- From the 7th century onwards, with the advent of Islam, these regions became part of the broader Islamic world, influencing local cultures and practices.

Faiths of Rulers and Subjects

- In 711 CE, Muhammad Qasim, an Arab general, conquered Sind, marking the beginning of Arab influence in the region. Later, the Turks and Afghans established the Delhi Sultanate in the 13th century and subsequent sultanates in the Deccan and other parts of the subcontinent.

- Islamic rulers, including the Mughals, followed a pragmatic approach towards non-Muslim subjects. They granted land endowments (waqf), tax exemptions, and respected the religious institutions of Hindus, Jains, Zoroastrians, Christians, and Jews.

- Non-Muslim subjects were categorized as zimmi, paying jizya (tax) for protection under Muslim rule. This status extended to Hindus as well under various Islamic rulers.

The Popular Practice of Islam

- Muslims in the subcontinent adhered to the core tenets of Islam: shahada (declaration of faith), salat (ritual prayer), zakat (charity), sawm (fasting during Ramadan), and hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca).

- Islam in the subcontinent was shaped by sectarian affiliations such as Sunni and Shi‘a, influencing local practices and interpretations of Islamic teachings.

- Arab Muslim traders along the Malabar coast (Kerala) adopted local customs like matriliny and matrilocal residence, blending Islamic faith with regional traditions.

- Mosques in the subcontinent exhibit a blend of universal Islamic architectural elements and regional variations. Universal features include the mihrab (prayer niche) and minbar (pulpit), oriented towards Mecca.

- Differences in mosque roofs, building materials, and decorative styles reflect local artistic traditions and building techniques, demonstrating cultural integration.

Names for Communities

- Early Indian texts rarely used terms like "Muslim" or "Hindu" to denote religious communities. Instead, people were often identified by regional or ethnic labels (e.g., Turushka for Turks, Tajika for Tajiks).

- Terms were used for migrant communities who did not adhere to caste norms or Sanskrit-based languages, highlighting cultural and linguistic diversity. For instance, Turks and Afghans were referred to as Shakas. Migrants were more generally known as mlechchha.

- Over time, terms like "Muslim" and "Hindu" gained prominence as markers of religious identity, reflecting evolving social and political contexts in the subcontinent.

Muhammad Qasim's conquest of Sind

Muhammad Qasim's conquest of Sind

The Growth of Sufism

In the early centuries of Islam, Sufism emerged as a spiritual and mystical movement in response to what some perceived as the growing materialism and institutionalization of the Caliphate. Sufis were religious-minded individuals who turned to asceticism and mysticism as a form of protest. They criticized the dogmatic interpretations of the Qur'an and traditions of the Prophet (sunna) adopted by mainstream theologians, instead emphasizing intense devotion, love for God, and following the example of Prophet Muhammad.

Khanqahs and Silsilas

Khanqahs:

- Definition: Khanqahs were hospices where Sufis organized communities around a teaching master or shaikh. The term "khanqah" is Persian.

- Leadership: The khanqah was typically controlled by a shaikh, pir, or murshid, who served as a spiritual guide.

- Discipleship: The shaikh enrolled disciples known as murids, and there was a system of appointing a successor (khalifa).

- Spiritual Conduct: Rules for spiritual conduct and interactions within the community were established.

Hijron ka Khanqah

Hijron ka Khanqah

Silsilas:

- Definition: Silsila means a chain, symbolizing a continuous spiritual link from master to disciple, ultimately tracing back to Prophet Muhammad.

- Transmission of Power: Spiritual power and blessings were believed to be transmitted through this unbroken chain.

- Initiation Rituals: Initiates underwent special rituals, including an oath of allegiance, wearing a patched garment, and shaving their hair.

- Tomb-Shrine: Upon the shaikh's death, the tomb-shrine (dargah) became a center of devotion, and pilgrimages (ziyarat) were made, particularly on the death anniversary or urs.

Outside the Khanqah

Some mystics initiated movements with radical interpretations of Sufi ideals, often rejecting the traditional khanqah system:

- Radical Movements: Certain mystics rejected khanqahs and adopted practices such as mendicancy, celibacy, and extreme asceticism.

- Alternative Names: Different groups emerged with names like Qalandars, Madaris, Malangs, and Haidaris.

- Defiance of Shari‘a: These groups, due to their intentional non-compliance with shari‘a (Islamic law), were often labeled as be-shari‘a, in contrast to ba-shari‘a Sufis who adhered to it.

The Chishtis in the Subcontinent

In the late twelfth century, several Sufi groups migrated to India, among which the Chishtis emerged as the most influential. This influence stemmed from their successful adaptation to the local environment and their incorporation of Indian devotional traditions.

Life in the Chishti Khanqah

Shaikh Nizamuddin’s Khanqah:

- Located on the banks of the river Yamuna in Ghiyaspur, on the outskirts of Delhi.

- Structure included small rooms, a large hall (jama’at khana), and a veranda with a boundary wall.

- Inhabitants: Family members, disciples, attendants, and visitors sought refuge during times of crisis, with an open kitchen (langar) based on unasked-for charity (futuh).

- Visitors varied widely, seeking spiritual guidance, healing amulets, or intercession from the Shaikh.

- Spiritual Succession: Shaikh Nizamuddin appointed successors who spread Chishti teachings and practices across the subcontinent.

Chishti Devotionalism: Ziyarat and Qawwali

Ziyarat (Pilgrimage)- Devotional visits to Sufi saints’ tombs (dargahs) seeking spiritual grace (barakat).

- Khwaja Muinuddin Chishti's dargah in Ajmer, known as "Gharib Nawaz," or comforter of the poor, was revered.

- Pilgrimage facilitated by its location on a major trade route.

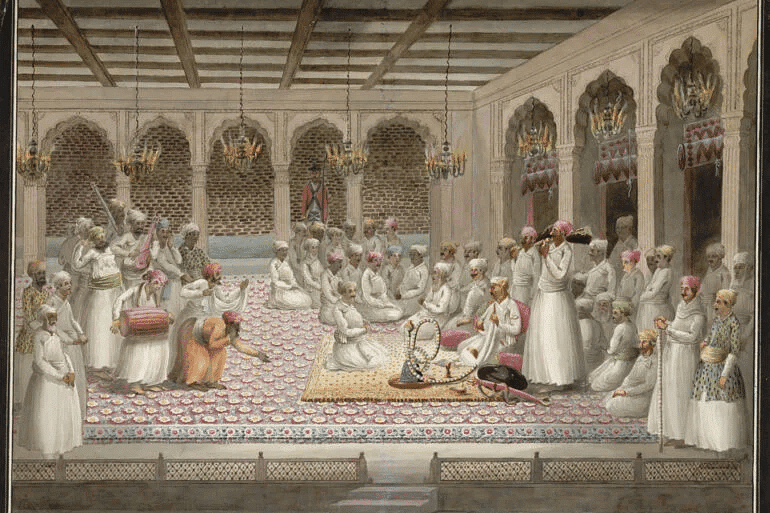

Qawwali:

- Mystical music integral to Chishti devotional practices.

- Performed by trained qawwals to induce divine ecstasy (sama‘) among listeners.

- Significant in spiritual gatherings (sama‘) at Chishti hospices.

Qawwali

Qawwali Languages and Communication

- Chishti Sufis in Delhi communicated in Hindavi, the vernacular language of the region. This choice facilitated direct communication with a broader audience beyond the scholarly and elite circles, enhancing accessibility to Sufi teachings and practices.

Prominent Chishti figures like Baba Farid and Amir Khusrau composed poetry in local languages. Baba Farid's verses, revered for their spiritual depth and simplicity, were later included in the Guru Granth Sahib, the central religious scripture of Sikhism. This integration not only highlighted the influence of Sufi spirituality on regional literatures but also enriched the cultural tapestry of medieval India.

Beyond practical communication, Chishti Sufis used local languages to express complex metaphysical concepts and spiritual teachings. For example, the "prem-akhyan" (love story) Padmavat by Malik Muhammad Jayasi used allegory to explore themes of divine love, resonating deeply with the cultural ethos of the region.

In regions like Bijapur in Karnataka, Chishti Sufis composed poetry in Dakhani, a variant of Urdu influenced by local cultural traditions. These poems were often sung by women during daily chores, contributing to the cultural and linguistic diversity of Sufi expressions across India.

Sufis and the State

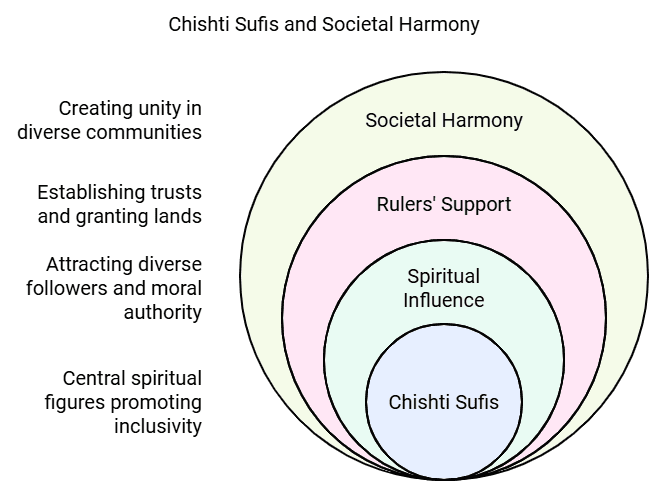

Chishti Sufis lived simple, spiritual lives but accepted donations from rulers to cover basic needs like food, clothing, and ritual practices, including sama‘ (mystical music) used in their spiritual gatherings.

Rulers often sought the support of Chishti Sufis to gain legitimacy among different communities, including non-Muslims. In return, rulers set up charitable trusts (auqaf) and gave tax-free lands (inam) to Sufi hospices, creating a mutually beneficial relationship.

Chishti Sufis gave rulers moral support and legitimacy due to their spiritual influence and perceived miraculous powers, which attracted people from all walks of life. This helped rulers strengthen their authority and unite society. However, there were sometimes tensions over titles and honors, highlighting the power dynamics between the spiritual and political authorities.

Despite this, Chishti Sufis maintained their moral authority by promoting inclusivity and compassion, helping to create social harmony in a diverse medieval India.

Chishti Sufis played a key role in fostering social unity and tolerance. Their hospices welcomed people from all social backgrounds, promoting unity amid cultural and religious diversity. This role enhanced their appeal and contributed to their lasting legacy in Indian history and culture.

New Devotional Paths Dialogue and Dissent in Northern India

Many poet-saints engaged in explicit and implicit dialogue with these new social situations, ideas, and institutions. Let us now see how this dialogue found expression. We focus here on three of the most influential figures of the time.Weaving a divine fabric: Kabir

- Kabir (c. fourteenth-fifteenth centuries) is perhaps one of the most outstanding examples of a poet-saint who emerged within this context. Historians have painstakingly tried to reconstruct his life and times through a study of compositions attributed to him as well as later hagiographies.

- Verses ascribed to Kabir have been compiled in three distinct but overlapping traditions. The Kabir Bijak is preserved by the Kabirpanth (the path or sect of Kabir) in Varanasi and elsewhere in Uttar Pradesh; the Kabir Granthavali is associated with the Dadupanth in Rajasthan, and many of his compositions are found in the Adi Granth Sahib

- Also striking is the range of traditions Kabir drew on to describe the Ultimate Reality. These include Islam: he described the Ultimate Reality as Allah, Khuda, Hazrat, and Pir. He also used terms drawn from Vedantic traditions, alakh (the unseen), nirakar (formless), Brahman, Atman, etc. Other terms with mystical connotations such as shabda (sound) or shunya (emptiness) were drawn from yogic traditions. Diverse and sometimes conflicting ideas are expressed in these poems.

- Just as Kabir’s ideas probably crystallised through dialogue and debate (explicit or implicit) with the traditions of sufis and yogis in the region of Awadh (part of present-day Uttar Pradesh), his legacy was claimed by several groups, who remembered him and continue to do so.

Kabir Das

Kabir Das

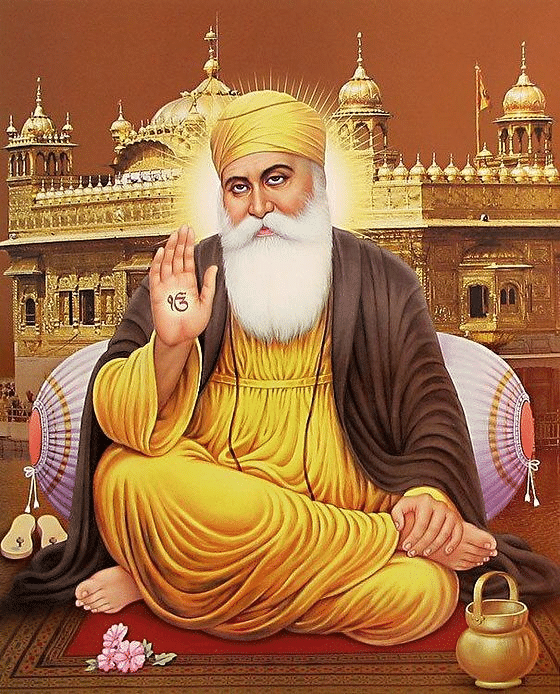

Baba Guru Nanak and the Sacred Word

- Baba Guru Nanak (1469-1539) was born in a Hindu merchant family in a village called Nankana Sahib near the river Ravi in the predominantly Muslim Punjab. He trained to be an accountant and studied Persian. He was married at a young age but he spent most of his time among sufis and bhaktas.

- The message of Baba Guru Nanak is spelt out in his hymns and teachings. These suggest that he advocated a form of nirguna bhakti, believing that the Absolute or "rab" had no gender or form. He firmly repudiated the external practices of the religions he saw around him.

- Baba Guru Nanak organized his followers into a community. He set up rules for congregational worship (sangat) involving collective recitation. He appointed one of his disciples, Angad, to succeed him as the preceptor (guru), and this practice was followed for nearly 200 years.

- It appears that Baba Guru Nanak did not wish to establish a new religion, but after his death, his followers consolidated their own practices and distinguished themselves from both Hindus and Muslims. The fifth preceptor, Guru Arjan, compiled Baba Guru Nanak’s hymns along with those of his four successors and other religious poets like Baba Farid, Ravidas (also known as Raidas), and Kabir in the Adi Granth Sahib. These hymns, called “gurbani,” are composed in various languages.

- In the late seventeenth century, the tenth preceptor, Guru Gobind Singh, included the compositions of the ninth guru, Guru Tegh Bahadur, and this scripture was called the Guru Granth Sahib.

- Guru Gobind Singh also laid the foundation of the Khalsa Panth (army of the pure) and defined its five symbols: uncut hair, a dagger, a pair of shorts, a comb, and a steel bangle. Under him, the community got consolidated as a socio-religious and military force.

Gurū Nānak

Gurū Nānak

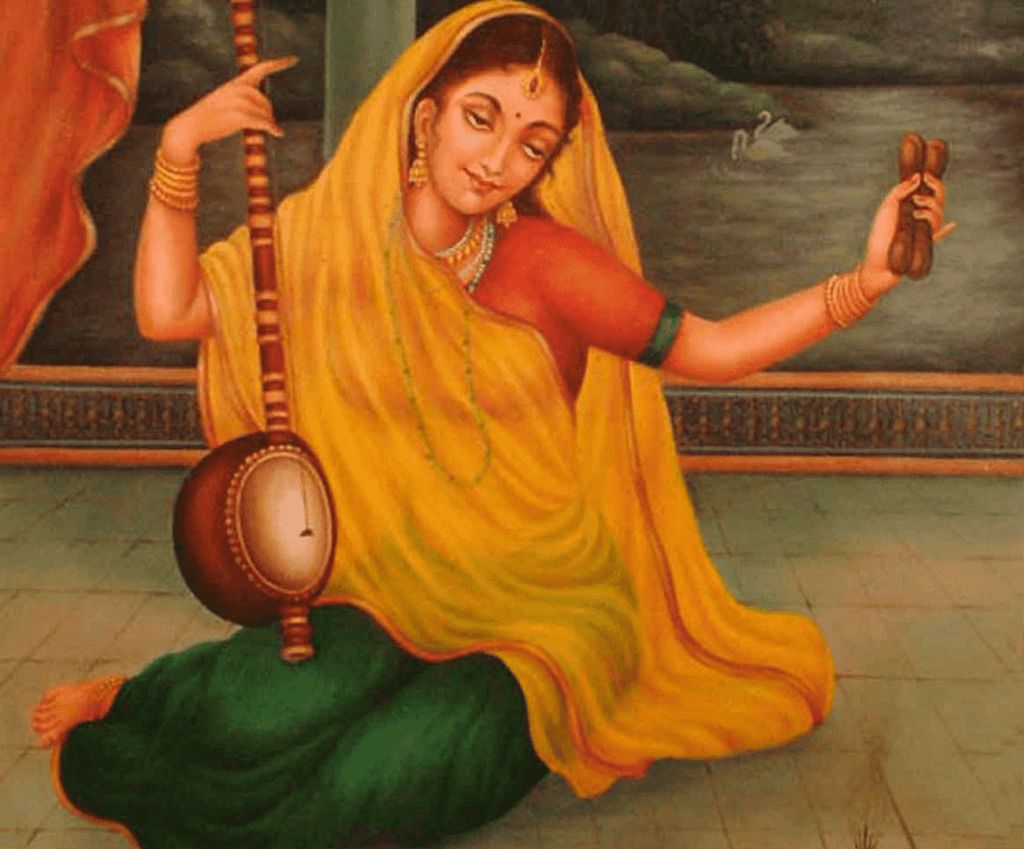

Mirabai, the Devotee Princess

- Mirabai (c. fifteenth-sixteenth centuries) is perhaps the best-known woman poet within the bhakti tradition.

- Biographies have been reconstructed primarily from the bhajans attributed to her, which were transmitted orally for centuries. According to these, she was a Rajput princess from Merta in Marwar who was married against her wishes to a prince of the Sisodia clan of Mewar, Rajasthan. She defied her husband and did not submit to the traditional role of wife and mother, instead recognizing Krishna, the avatar of Vishnu, as her lover.

- According to some traditions, her preceptor was Raidas, a leather worker. This would indicate her defiance of the norms of caste society. After rejecting the comforts of her husband’s palace, she is supposed to have donned the white robes of a widow or the saffron robe of the renouncer.

- Although Mirabai did not attract a sect or group of followers, she has been recognized as a source of inspiration for centuries. Her songs continue to be sung by women and men, especially those who are poor and considered “low caste” in Gujarat and Rajasthan.

Saint Mirabai

Saint Mirabai

These three figures—Kabir, Baba Guru Nanak, and Mirabai—illustrate the diverse ways in which poet-saints engaged with and responded to the social, religious, and cultural transformations in Northern India during their respective times.

Reconstructing Histories of Religious Traditions

Sculpture and Architecture provide insights into religious practices and beliefs. Understanding them requires contextual knowledge of the societies that produced and utilized these artworks.

- Written in a direct and straightforward language, these compositions express spiritual and philosophical ideas within the context of Bhakti movement in South India.

- These royal decrees were typically written in ornate Persian. They offer insights into political-religious policies and administrative practices during the Mughal period.

- Texts range from the poetic and allegorical to the administrative and legal, each requiring a different interpretive approach.

- Understanding the context in which texts were produced is essential for deciphering their meanings and implications for religious beliefs and practices.

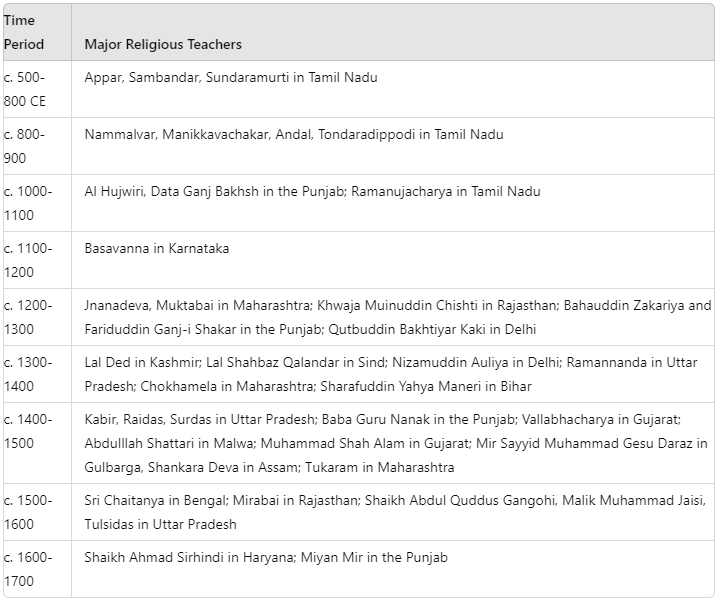

Timeline

Conclusion

Historians reconstruct India's religious history through sculpture, architecture, and diverse texts, revealing intricate interactions and profound shifts. Poet-saints like Kabir, Baba Guru Nanak, and Mirabai illuminate paths of dissent and dialogue amidst transformations. As India's religious tapestry evolves, these narratives remind us of its enduring complexity and resilience, contributing uniquely to its vibrant civilization.

|

30 videos|274 docs|25 tests

|

FAQs on Bhakti- Sufi Traditions Class 12 History

| 1. What is the significance of the Bhakti movement in Indian religious traditions? |  |

| 2. How did Sufism influence the spiritual landscape of the Indian subcontinent? |  |

| 3. Who were the Chishti order, and what was their role in the spread of Sufism in India? |  |

| 4. What are the main characteristics of the Virashaiva tradition in Karnataka? |  |

| 5. How did the dialogue and dissent among different religious traditions shape northern India’s spiritual landscape? |  |