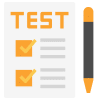

The photoelectric effect refers to the phenomenon where electrons are expelled from a metal's surface upon exposure to light. These expelled electrons are known as photoelectrons. Notably, the emission of photoelectrons and their kinetic energy rely on the frequency of the incident light. This process, wherein light causes the ejection of photoelectrons from a metal's surface, is commonly termed photoemission.

The photoelectric effect occurs due to the absorption of energy by electrons at the metal's surface from the incident light. This absorbed energy enables the electrons to overcome the attractive forces that bind them to the metal's nuclei. Below is an illustration illustrating the emission of photoelectrons as a consequence of the photoelectric effect.

History of the Photoelectric Effect

The history of the photoelectric effect dates back to 1887 when Wilhelm Ludwig Franz Hallwachs introduced the concept. Heinrich Rudolf Hertz then conducted experiments to verify this phenomenon. Their observations revealed that when a surface is exposed to electromagnetic radiation above a certain frequency threshold, the radiation is absorbed, leading to the emission of electrons. Today, the photoelectric effect is studied as the absorption of electromagnetic radiation by a material, resulting in the release of electrically charged particles.

To be more precise, in the photoelectric effect, when light falls on the surface of a metal, it causes the ejection of electrons. These ejected electrons are referred to as photoelectrons (e–). The resulting flow of electrons is known as the photoelectric current.

Explaining the Photoelectric Effect: The Concept of Photons

The photoelectric effect cannot be explained by considering light as a wave. However, this phenomenon can be explained by the particle nature of light, in which light can be visualised as a stream of particles of electromagnetic energy. These ‘particles’ of light are called photons. The energy held by a photon is related to the frequency of the light via Planck’s equation.

E = h𝜈 = hc/λ

Where,

- E denotes the energy of the photon

- h is Planck’s constant

- 𝜈 denotes the frequency of the light

- c is the speed of light (in a vacuum)

- λ is the wavelength of the light

Thus, it can be understood that different frequencies of light carry photons of varying energies. For example, the frequency of blue light is greater than that of red light (the wavelength of blue light is much shorter than the wavelength of red light). Therefore, the energy held by a photon of blue light will be greater than the energy held by a photon of red light.

Threshold Energy for the Photoelectric Effect

In order for the photoelectric effect to take place, the photons that reach the metal surface must possess enough energy to overcome the attractive forces holding the electrons to the nuclei of the metal. The minimum amount of energy required to dislodge an electron from the metal is known as the threshold energy (symbolized by Φ).

When a photon's energy matches the threshold energy, its frequency is equivalent to the threshold frequency, which represents the minimum frequency of light necessary for the photoelectric effect to occur. The threshold frequency is typically denoted as 𝜈th, while the corresponding wavelength, known as the threshold wavelength, is symbolized as λth. The relationship between the threshold energy and the threshold frequency can be expressed as follows:

Φ = h𝜈th = hc/λth

Relationship between the Frequency of the Incident Photon and the Kinetic Energy of the Emitted Photoelectron

Therefore, the relationship between the energy of the photon and the kinetic energy of the emitted photoelectron can be written as follows:

Ephoton = Φ + Eelectron

⇒ h𝜈 = h𝜈th + ½mev2

Where,

- Ephoton denotes the energy of the incident photon, which is equal to h𝜈

- Φ denotes the threshold energy of the metal surface, which is equal to h𝜈th

- Eelectron denotes the kinetic energy of the photoelectron, which is equal to ½mev2 (me = Mass of electron = 9.1*10-31 kg)

If the energy of the photon is less than the threshold energy, there will be no emission of photoelectrons (since the attractive forces between the nuclei and the electrons cannot be overcome). Thus, the photoelectric effect will not occur if 𝜈 < 𝜈th. If the frequency of the photon is exactly equal to the threshold frequency (𝜈 = 𝜈th), there will be an emission of photoelectrons, but their kinetic energy will be equal to zero. An illustration detailing the effect of the frequency of the incident light on the kinetic energy of the photoelectron is provided below.

From the image, it can be observed that

- The photoelectric effect does not occur when the red light strikes the metallic surface because the frequency of red light is lower than the threshold frequency of the metal.

- The photoelectric effect occurs when green light strikes the metallic surface, and photoelectrons are emitted.

- The photoelectric effect also occurs when blue light strikes the metallic surface. However, the kinetic energies of the emitted photoelectrons are much higher for blue light than for green light. This is because blue light has a greater frequency than green light.

It is important to note that the threshold energy varies from metal to metal. This is because the attractive forces that bind the electrons to the metal are different for different metals. It can also be noted that the photoelectric effect can also take place in non-metals, but the threshold frequencies of non-metallic substances are usually very high.

Einstein’s Contributions towards the Photoelectric Effect

The photoelectric effect is the process that involves the ejection or release of electrons from the surface of materials (generally a metal) when light falls on them. The photoelectric effect is an important concept that enables us to clearly understand the quantum nature of light and electrons.

After continuous research in this field, the explanation for the photoelectric effect was successfully explained by Albert Einstein. He concluded that this effect occurred as a result of light energy being carried in discrete quantised packets. For this excellent work, he was honoured with the Nobel Prize in 1921.

According to Einstein, each photon of energy E is

E = hν

Where E = Energy of the photon in joule

h = Plank’s constant (6.626 × 10-34 J.s)

ν = Frequency of photon in Hz

Properties of the Photon

- For a photon, all the quantum numbers are zero.

- A photon does not have any mass or charge, and they are not reflected in a magnetic and electric field.

- The photon moves at the speed of light in empty space.

- During the interaction of matter with radiation, radiation behaves as it is made up of small particles called photons.

- Photons are virtual particles. The photon energy is directly proportional to its frequency and inversely proportional to its wavelength.

The momentum and energy of the photons are related, as given below

E = p.c where

p = Magnitude of the momentum

c = Speed of light

Definition of the Photoelectric Effect

The phenomenon of metals releasing electrons when they are exposed to light of the appropriate frequency is called the photoelectric effect, and the electrons emitted during the process are called photoelectrons.

Principle of the Photoelectric Effect

The law of conservation of energy forms the basis for the photoelectric effect.

Minimum Condition for Photoelectric Effect

Threshold Frequency (γth)It is the minimum frequency of the incident light or radiation that will produce a photoelectric effect, i.e., the ejection of photoelectrons from a metal surface is known as the threshold frequency for the metal. It is constant for a specific metal but may be different for different metals.

If γ = Frequency of the incident photon and γth = Threshold frequency, then,

- If γ < γTh, there will be no ejection of photoelectron and, therefore, no photoelectric effect.

- If γ = γTh, photoelectrons are just ejected from the metal surface; in this case, the kinetic energy of the electron is zero.

- If γ > γTh, then photoelectrons will come out of the surface, along with kinetic energy.

Threshold Wavelength (λth)

During the emission of electrons, a metal surface corresponding to the greatest wavelength to incident light is known as threshold wavelength.

λth = c/γth

For wavelengths above this threshold, there will be no photoelectron emission. For λ = wavelength of the incident photon, then

- If λ < λTh, then the photoelectric effect will take place, and ejected electron will possess kinetic energy.

- If λ = λTh, then just the photoelectric effect will take place, and the kinetic energy of ejected photoelectron will be zero.

- If λ > λTh, there will be no photoelectric effect.

Work Function or Threshold Energy (Φ)

The minimal energy of thermodynamic work that is needed to remove an electron from a conductor to a point in the vacuum immediately outside the surface of the conductor is known as work function/threshold energy.

Φ = hγth = hc/λth

The work function is the characteristic of a given metal. If E = energy of an incident photon, then

- If E < Φ, no photoelectric effect will take place.

- If E = Φ, just a photoelectric effect will take place, but the kinetic energy of ejected photoelectron will be zero

- If E > photoelectron will be zero

- If E > Φ, the photoelectric effect will take place along with the possession of the kinetic energy by the ejected electron.

Photoelectric Effect Formula

According to Einstein’s explanation of the photoelectric effect, The energy of photon = Energy needed to remove an electron + Kinetic energy of the emitted electron

i.e., hν = W + E

Where,

- h is Planck’s constant

- ν is the frequency of the incident photon

- W is a work function

- E is the maximum kinetic energy of ejected electrons: 1/2 mv2

Laws Governing the Photoelectric Effect

- For a light of any given frequency,; (γ > γTh), the photoelectric current is directly proportional to the intensity of light.

- For any given material, there is a certain minimum (energy) frequency, called threshold frequency, below which the emission of photoelectrons stops completely, no matter how high the intensity of incident light is.

- The maximum kinetic energy of the photoelectrons is found to increase with the increase in the frequency of incident light, provided the frequency (γ > γTh) exceeds the threshold limit. The maximum kinetic energy is independent of the intensity of light.

- The photo-emission is an instantaneous process.

|

Download the notes

Photoelectric Effect

|

Download as PDF |

Experimental Study of the Photoelectric Effect

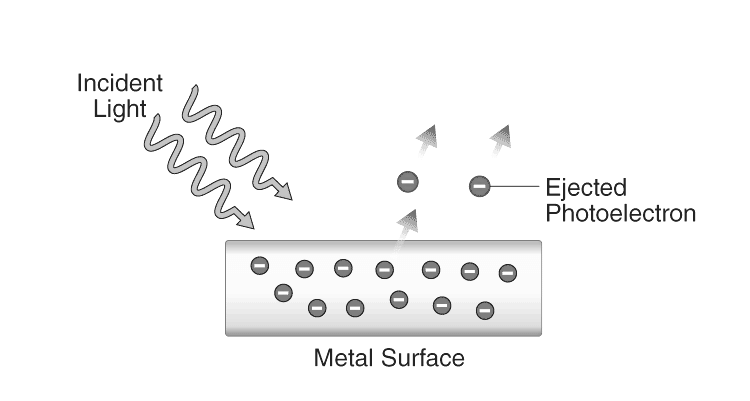

Photoelectric Effect: Experimental Setup

Photoelectric Effect: Experimental Setup

The given experiment is used to study the photoelectric effect experimentally. In an evacuated glass tube, two zinc plates, C and D, are enclosed. Plates C acts as an anode, and D acts as a photosensitive plate.

Two plates are connected to battery B and ammeter A. If the radiation is incident on plate D through a quartz window, W electrons are ejected out of the plate, and current flows in the circuit. This is known as photocurrent. Plate C can be maintained at desired potential (+ve or – ve) with respect to plate D.

Characteristics of the Photoelectric Effect

- The threshold frequency varies with the material, it is different for different materials.

- The photoelectric current is directly proportional to the light intensity.

- The kinetic energy of the photoelectrons is directly proportional to the light frequency.

- The stopping potential is directly proportional to the frequency, and the process is instantaneous.

Factors Affecting the Photoelectric Effect

With the help of this apparatus, we will now study the dependence of the photoelectric effect on the following factors:

- The intensity of incident radiation.

- A potential difference between the metal plate and collector.

- Frequency of incident radiation.

Effects of Intensity of Incident Radiation on Photoelectric Effect

The potential difference between the metal plate, collector and frequency of incident light is kept constant, and the intensity of light is varied.

The electrode C, i.e., the collecting electrode, is made positive with respect to D (metal plate). For a fixed value of frequency and the potential between the metal plate and collector, the photoelectric current is noted in accordance with the intensity of incident radiation.

It shows that photoelectric current and intensity of incident radiation both are proportional to each other. The photoelectric current gives an account of the number of photoelectrons ejected per sec.

Effects of Potential Difference between the Metal Plate and the Collector on the Photoelectric Effect

The frequency of incident light and intensity is kept constant, and the potential difference between the plates is varied.

Keeping the intensity and frequency of light constant, the positive potential of C is increased gradually. Photoelectric current increases when there is a positive increase in the potential between the metal plate and the collector up to a characteristic value.

There is no change in photoelectric current when the potential is increased higher than the characteristic value for any increase in the accelerating voltage. This maximum value of the current is called saturation current.

Effect of Frequency on Photoelectric Effect

The intensity of light is kept constant, and the frequency of light is varied.

For a fixed intensity of incident light, variation in the frequency of incident light produces a linear variation of the cut-off potential/stopping potential of the metal. It is shown that the cut-off potential (Vc) is linearly proportional to the frequency of incident light.

The kinetic energy of the photoelectrons increases directly proportionally to the frequency of incident light to completely stop the photoelectrons. We should reverse and increase the potential between the metal plate and collector in (negative value) so the emitted photoelectron can’t reach the collector.

Einstein’s Photoelectric Equation

According to Einstein’s theory of the photoelectric effect, when a photon collides inelastically with electrons, the photon is absorbed completely or partially by the electrons. So if an electron in a metal absorbs a photon of energy, it uses the energy in the following ways.

Some energy Φ0 is used in making the surface electron free from the metal. It is known as the work function of the material. Rest energy will appear as kinetic energy (K) of the emitted photoelectrons.

Einstein’s Photoelectric Equation Explains the Following Concepts

- The frequency of the incident light is directly proportional to the kinetic energy of the electrons, and the wavelengths of incident light are inversely proportional to the kinetic energy of the electrons.

- If γ = γth or λ =λth then vmax = 0

- γ < γth or λ > λth: There will be no emission of photoelectrons.

- The intensity of the radiation or incident light refers to the number of photons in the light beam. More intensity means more photons and vice-versa. Intensity has nothing to do with the energy of the photon. Therefore, the intensity of the radiation is increased, and the rate of emission increases, but there will be no change in the kinetic energy of electrons. With an increasing number of emitted electrons, the value of the photoelectric current increases.

Different Graphs of the Photoelectric Equation

- Photoelectric current vs Retarding potential for different voltages

- Photoelectric current vs Retarding potential for different intensities

- Electron current vs Light Intensity

- Stopping potential vs Frequency

- Electron current vs Light frequency

- Electron kinetic energy vs Light frequency

Applications of the Photoelectric Effect

The photoelectric effect finds diverse applications in various fields. Here are some notable examples:

- Solar Panels: The photoelectric effect is utilized in generating electricity through solar panels. These panels contain specific metal combinations that enable the generation of electricity from a wide range of wavelengths.

- Motion and Position Sensors: By employing a photoelectric material in conjunction with a UV or IR LED, motion and position sensors are created. When an object interrupts the light between the LED and the sensor, the electronic circuit detects a change in potential difference.

- Lighting Sensors: The photoelectric effect is employed in lighting sensors found in smartphones and other devices. These sensors enable automatic adjustment of screen brightness based on the intensity of light hitting the sensor, as the current generated via the photoelectric effect is proportional to the light's intensity.

- Digital Cameras: Digital cameras rely on photoelectric sensors to detect and record light. These sensors respond to different colors of light, enabling the camera to capture accurate images.

- X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS): XPS employs the photoelectric effect by irradiating a surface with X-rays and measuring the kinetic energies of emitted electrons. This technique provides valuable information about the surface's chemistry, including elemental and chemical composition.

- Burglar Alarms: Photoelectric cells are utilized in burglar alarms to detect any changes in light levels, triggering an alarm when light is interrupted or altered.

- Photomultipliers: The photoelectric effect is used in photomultipliers to detect low levels of light by amplifying the signals produced by photoelectrons.

- Early Television: In the early days of television, video camera tubes utilized the photoelectric effect to detect and capture light for broadcasting purposes.

- Night Vision Devices: Night vision devices rely on the photoelectric effect to enhance visibility in low-light conditions, allowing users to see in the dark.

- Chemical Analysis and Nuclear Processes: The photoelectric effect contributes to the study of certain nuclear processes and aids in chemical analysis. The emitted electrons carry specific energies characteristic of the atomic source, providing valuable information about elemental composition, chemical composition, empirical formula of compounds, and chemical state.

Example: In a photoelectric effect experiment, the threshold wavelength of incident light is 260 nm and E (in eV) = 1237/λ (nm). Find the maximum kinetic energy of emitted electrons.

Solution:

Kmax = hc/λ – hc/λ0 = hc × [(λ0 – λ)/λλ0]

⇒ Kmax = (1237) × [(380 – 260)/380×260] = 1.5 eV

Therefore, the maximum kinetic energy of emitted electrons in the photoelectric effect is 1.5 eV.