Porifera: Reproduction | Zoology Optional Notes for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Spermatogenesis |

|

| Oogenesis |

|

| Fertilization |

|

| Development |

|

| Asexual Reproduction in Sponges |

|

| Regeneration in Sponges |

|

| Wilson's Experiment |

|

While some sponge species can be unisexual, the majority of sponges are either monoecious or bisexual. Despite being hermaphrodites, sponges typically undergo cross-fertilization due to differences in the timing of sperm and egg production. Both sperm and eggs originate from undifferentiated amoebocytes known as archaeocytes. Choanocytes can also give rise to sperm and eggs through gametogenesis. Sponges display either protandry, where they produce sperm first and eggs later, or protogyny, where they produce eggs first and sperm later. Both protandry and protogyny serve to facilitate cross-fertilization.

Spermatogenesis

- Spermatogenesis is the process by which male reproductive cells, or sperm, are produced. It begins with a spermatogonium, a specialized cell, which is surrounded by one or more flattened covering cells, forming a structure known as a spermatocyst.

- These covering cells are derived from other amoebocyte cells. The spermatogonia then undergo two to three maturation divisions, resulting in the formation of spermatocytes. These spermatocytes eventually develop into spermatozoa, which are mature sperm cells.

- A mature spermatozoon is characterized by a rounded nucleated head and a tail. The tail has a lashing movement that aids the spermatozoon in reaching other sponges for fertilization.

Oogenesis

- The process of oogenesis involves the development of the egg mother cell, known as an oocyte. This oocyte is derived from large archaeocytes that possess a distinct nucleus. In some cases, oocytes can also originate from choanocytes.

- The oocyte exhibits amoeboid movement, engulfing other cells as it progresses. These engulfed cells serve as support or nursing cells for the oocyte. Once the oocyte reaches full maturity, it undergoes two maturation divisions to become an ovum.

- The ovum is situated within the wall of the radial canal or spongocoel, poised to be fertilized by the sperm from another sponge.

Fertilization

- During fertilization, sperm cells are expelled from a sponge as they exit through the osculum via the outgoing water flow. These released sperm cells then travel into another sponge through incoming water, facilitated by the ostia.

- Choanocytes play a crucial role as nurse cells by assisting in the transportation of sperm cells to the ova, which are situated in the flagellated choanoderm.

- It's important to note that the fertilization process is internal and occurs in a cross-fertilization manner.

Development

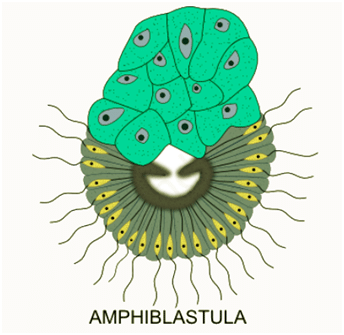

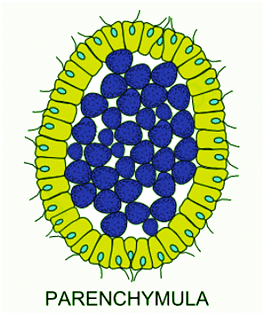

Early development takes place within the maternal sponge leading to the formation of larval stages. The larval stages bear flagella, which help them to escape out from the maternal sponge body. The larva thus escaped gets attached to a suitable substratum, metamorphose and grow into adult sponge. Sponges have two types of larvae.

- Amphiblastula: It is hollow, oval larval stage characteristic of calcareous sponges (Scypha). Anterior half of amphiblastula bears flagella while the posterior half is free from flagella.

- Parenchymula: It is solid, oval or flattened larval stage characteristic of calcareous sponges, Hexactanellida and most Desmospongia. The entire larva is covered by flagella.

- With the help of external flagella, the motile larvae escapes from the parental body and swim for a few hours to many days. Finally they settle down, become attached to some solid object, metamorphose and grow into an adult.

Asexual Reproduction in Sponges

Asexual reproduction in sponges is by

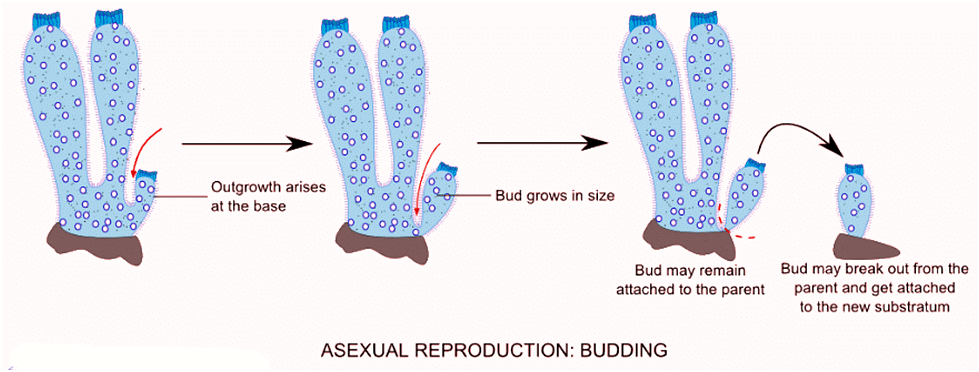

1. Budding

By this method the number of individuals in the colony may increase or new colonies may be formed. An outgrowth from the sponge body wall may arise either at the base or near the attached end to form bud. This bud is the result of bulging of pinacoderm to receive numerous archeocytes collected at the internal surface of the body wall.

The bud so formed grows in size, breaks off an osculum at its free distal end and thus becomes an adult individual. It either remains attached to the parent sponge or may get detached to form a new sponge by fixing itself to a suitable substratum.

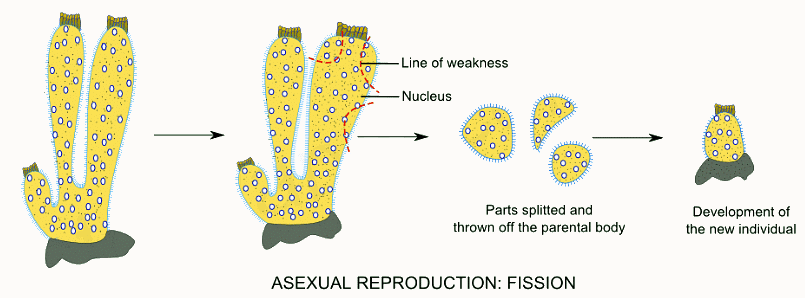

2. Fission

In this type of reproduction parts of the sponge body are thrown off from the sponge body. The sponge is hypertrophied over a limited area developing a line of weakness. Hypertrophy is the non-tumorous enlargement of a tissue or an organ as a result of the increase in the size rather than the number of constituent cells.

Along this weak line, splitting occurs and this part is thrown off. The part of parental sponge thus thrown off develops into an adult individual, breaks off an osculum at its free distal end and gets attached to a suitable substratum. This new individual develops a new colony by budding.

|

Download the notes

Porifera: Reproduction

|

Download as PDF |

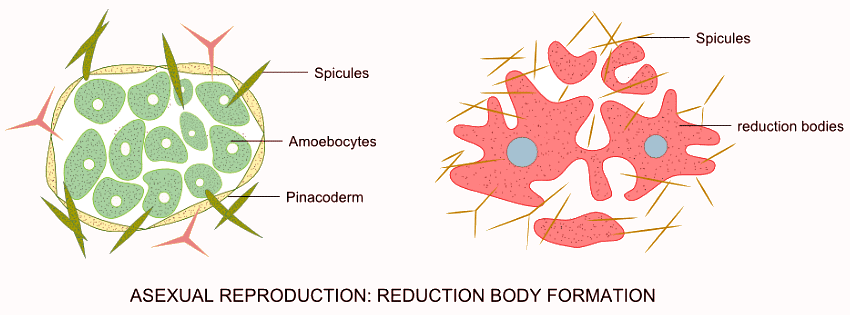

3. Formation of reduction bodies

It is very unusual method of asexual reproduction found in sponges. Some fresh water and marine sponges get disintegrated during adverse conditions. During unfavourable conditions, the sponge collapse leaving small rounded balls called as reduction bodies.

Each reduction body consists of internal mass of amoebocytes covered externally by pinacoderm. When the favourable conditions return, each reduction body develops into a complete new sponge. It gets attached to a suitable substratum and breaks off an osculum at its free distal end.

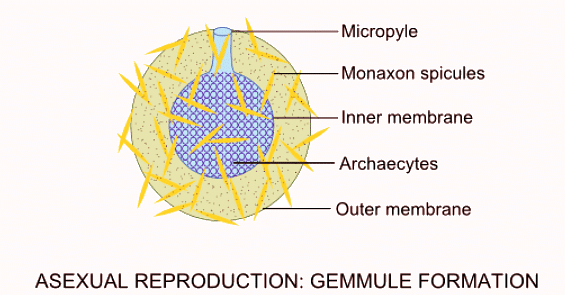

4. Formation of gemmules

Gemmules are internals buds formed within the sponge body. It is the characteristic feature of all fresh water and some marine forms like Ficula and Tethya. Gemmules eventually get detached when the parent sponge is decayed. Gemmules help the sponge to tide over unfavourable conditions. Gemmules can withstand freezing and considerably greater degree of desiccation than the adult sponges.

- A gemmule is a small, round, hard ball consisting of internal mass of food laden archaeocytes surrounded by chitinous double membrane. The outer protective membrane may be strengthened by siliceous amphidisc spicules (Ephidatia) or by monaxon spicules (Spongilla).

- In autumn fresh water sponges suffering from cold and food scarcity get disintegrated leaving behind number of gemmules which remain inert throughout the winter. Gemmules are set free after the decay of the parent sponge.

- The gemmules thus formed may sink to the bottom or may flow away with the water. In spring, when the conditions become suitable, the gemmules begin to hatch.

- The living contents of the gemmules escape out through the micropylar opening and form the new sponge. These new sponge gives rise to summer generation by producing spermatozoa and ova.

- The summer generation dies off in autumn living behind gemmules which hatch in spring. The life history of such sponges illustrates alternation of generation.

Regeneration in Sponges

- Regeneration is a remarkable ability found in various animals, particularly those with less specialized structures. This natural process allows them to replace lost or damaged body parts. The extent of regeneration varies, with simpler animals and tissues demonstrating a higher regenerative potential.

- For instance, sponges, which possess a relatively basic level of organization, exhibit a remarkable capacity for regeneration. Epithelial tissue can regenerate quite readily, whereas highly specialized tissues like muscle or nerve tissue have limited regenerative capabilities.

- Among all creatures, sponges stand out as masters of regeneration. Sponges can be divided into tiny fragments or even turned into a paste, and as long as they contain two vital cell types—collencytes (responsible for producing mesohyl, the gelatinous matrix in the sponge that forms a pseudo-tissue) and archaeocytes (responsible for generating all other cells within the sponge's body)—the sponge can endure and eventually reform into a spongelet and then into a mature sponge.

- Given the right environmental conditions, a sponge fragment equipped with these two cells can recover from severe injuries and return to its normal form in just a few weeks. This remarkable ability elevates sponges to a status as some of the most extraordinary animals in the natural world.

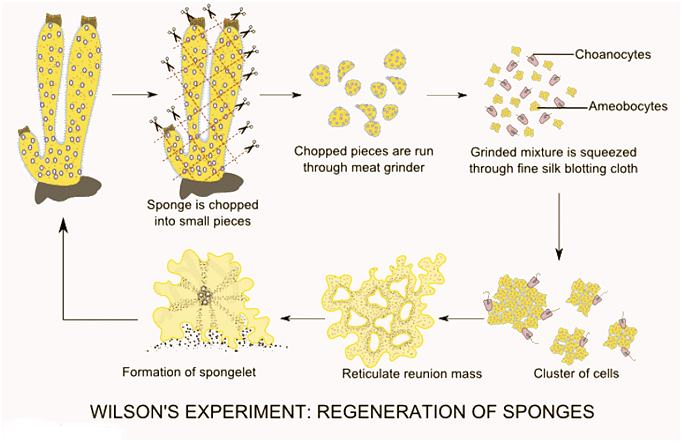

Wilson's Experiment

The regeneration power of sponges is demonstrated by the experiments carried out by Wilson in 1907.

- If a sponge is chopped into small pieces, run through a meat grinder and then squeezed through a fine blotting cloth then all the sponge cells are separated from each other. In a suitable some of these disunited cells unite to form small aggregates or spongelets.

- In course of several days these spongelets acquire canals, flagellated chambers and skeleton thus growing into new sponge. Cells from different species of sponges may adhere temporarily but later separate without re-forming a sponge.

Based on Bergquist's experiments, when a tissue is transplanted into a sponge from another sponge of the same species, the host and the graft will fuse and develop together. However, if the graft is from a different species, the host will reject it. In Humphrey's research, it was found that regeneration requires the presence of calcium and magnesium ions. Additionally, certain unidentified factors located on the cell surface are believed to play a crucial role in the regeneration process.

|

181 videos|346 docs

|

FAQs on Porifera: Reproduction - Zoology Optional Notes for UPSC

| 1. What is spermatogenesis? |  |

| 2. What is oogenesis? |  |

| 3. What is fertilization? |  |

| 4. How does fertilization occur? |  |

| 5. What is the role of porifera in reproduction? |  |