Indian Polity and Governance - 1 | Current Affairs & Hindu Analysis: Daily, Weekly & Monthly - UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Uniform Civil Code |

|

| Judicial Pendency |

|

| Directorate of Enforcement |

|

| The Multi-State Cooperative Societies (Amendment) Bill 2023 |

|

| The Cinematograph (Amendment) Bill 2023 |

|

Uniform Civil Code

The call for a Uniform Civil Code is generating apprehensions regarding religious rights and personal laws, especially as the Supreme Court's examination of religious freedom remains inconclusive.

What is UCC?

- UCC, or Uniform Civil Code, is the proposal advocating a standardized set of civil laws applicable to all citizens of a nation, irrespective of their religious or cultural backgrounds.

- The underlying principle of UCC is rooted in the ideals of equality and consistency in legal treatment, aiming to replace existing personal laws based on religious practices that govern aspects like marriage, divorce, inheritance, adoption, and succession.

Historical Perspectives on UCC:

- During British rule, civil matters lacked uniformity, with different communities following personal laws based on religious customs. The idea of a UCC emerged to address this fragmentation and promote a shared civil identity.

- Under Portuguese rule in Goa until 1961, a Uniform Civil Code, influenced by the Portuguese Napoleonic code, was implemented.

- Jawaharlal Nehru, envisioning a modern and progressive India, considered UCC crucial for nation-building. He believed it would eliminate religious-based divisions and foster equality among citizens.

- The Hindu Code Bill aimed to codify and modernize Hindu personal laws related to marriage, divorce, adoption, and inheritance. It was perceived as a step toward UCC by bringing uniformity within the Hindu community.

- The Supreme Court's judgment in the Shah Bano Case triggered debates on the necessity of UCC to ensure gender justice and equal rights for women across religious communities.

Constitutional Perspectives on UCC

- Constituent Assembly Debates: During the framing of the Indian Constitution, the debates witnessed diverse viewpoints, with some members advocating for a UCC as a way to promote gender equality and secularism, while others expressed concerns about preserving religious and cultural rights.

- Directive Principles of State Policy: Article 44 of the Indian constitution states that the state shall endeavour to secure for its citizens a uniform civil code throughout the territory of India.

- Secularism: The Indian Constitution enshrines the principle of secularism, which mandates the separation of religion and the state. A UCC is seen as a way to promote secularism by ensuring equal treatment of all citizens irrespective of their religious affiliations.

- Equality and Non-Discrimination: The Constitution of India guarantees equality before the law under Article 14, and prohibits discrimination on grounds of religion, race, caste, sex, or place of birth. UCC would uphold these principles by ensuring equal rights and equal treatment for all citizens, regardless of their religious backgrounds.

- Gender Justice: The Constitution also guarantees the right to equality and the right against discrimination based on gender. A UCC is seen as a means to promote gender justice.

Different communities, including Muslims, Hindus, Jains, Buddhists, Sikhs, Parsis, and Jews, are governed by their distinct personal laws. In Goa, the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) is in place, retaining its common family law, the Goa Civil Code, even after liberation from Portuguese rule in 1961. However, the rest of India follows various personal laws based on religious or community identity.

For instance:

- All Hindus: Governed by the Reformed Hindu Personal Law, applicable since the enactment of the Hindu Marriage Act, 1955. Renounced Hindus still fall under Hindu Law. Hindus married under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, continue to be governed by Hindu Personal Law.

- Muslims: Governed by Muslim Personal Law, but Muslims married under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, are no longer subject to Muslim Personal Law.

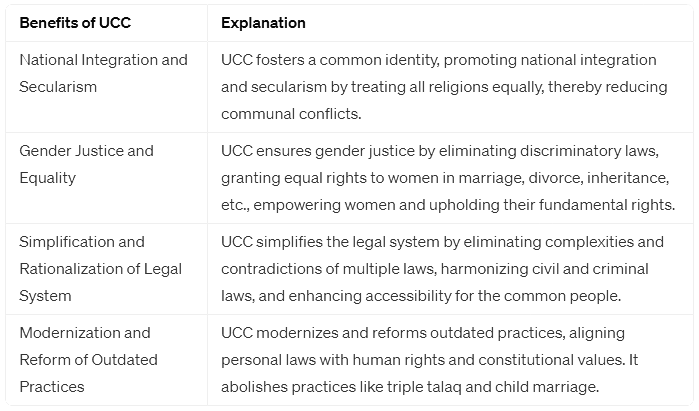

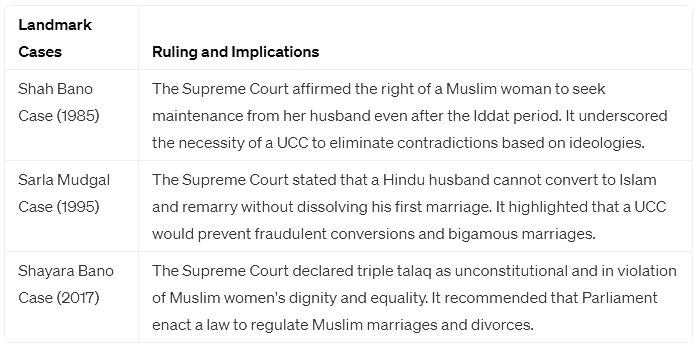

Argument in favor of UCC:

Argument Against UCC:

Law Commission Perspectives:

- The 21st Law Commission of India expressed that the "question of a uniform civil code is extensive, and its potential consequences, untested in India." It concluded that a "UCC is neither necessary nor desirable at this stage."

- In response, the government tasked the 22nd Law Commission of India with examining various issues related to the Uniform Civil Code.

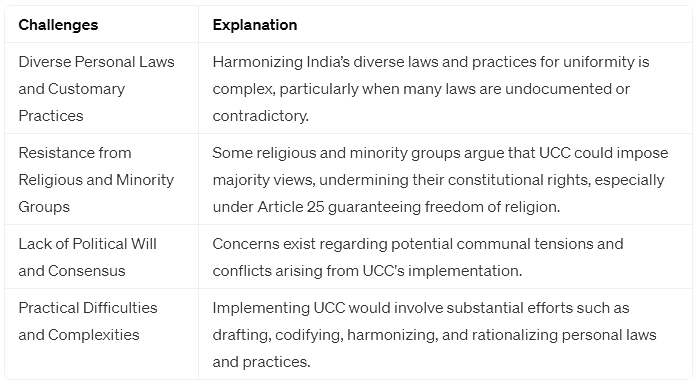

Supreme Court-Related Cases:

Conclusion

The introduction of a Uniform Civil Code (UCC) in India necessitates a nuanced approach that upholds the principles of multiculturalism and diversity. It is imperative to engage in comprehensive dialogues involving stakeholders such as religious leaders and legal experts, ensuring a thorough consideration of diverse viewpoints. The primary emphasis should be on eradicating practices that impede equality and gender justice, while steering clear of reactionary cultural perspectives. The process of reforming Muslim Personal Law should be spearheaded by the Muslim clergy, urging a critical examination of practices to advance principles of equality and justice. The ultimate goal is to craft a fair and inclusive UCC that remains aligned with constitutional values.

Judicial Pendency

In the Economic Survey 2018-19, it was revealed that the judicial system grapples with approximately 3.5 crore pending cases, predominantly concentrated in district and subordinate courts. A staggering 87.54 percent of the overall case backlog resides in these lower-tier courts, with over 64 percent of cases awaiting resolution for more than a year. In 2018, the average disposal time for civil and criminal cases in Indian District & Subordinate courts was 4.4 times and 6 times higher, respectively, than the average in Council of Europe member states in 2016.

- Remarkably, achieving a Case Clearance Rate of 100 percent, essentially eliminating case accumulation, requires the addition of only 2,279 judges in lower courts, 93 in High Courts, and just one in the Supreme Court. These numbers are well within the sanctioned strength and only necessitate filling existing vacancies.

- The World Bank's Ease of Doing Business Report for 2018 and 2019 highlights a concerning stagnation in the time taken to decide a case, remaining fixed at 1,445 days.

Challenges in the Judicial System

- The government emerges as the most significant litigant in the legal system.

- Inadequately formulated orders contribute to disputed tax revenues amounting to 4.7 percent of the GDP, with a rising trend.

- Investment is hindered as approximately Rs 50,000 crore remains entangled in stalled projects, a consequence of court-issued injunctions and stay orders stemming from poorly drafted and poorly reasoned judicial decisions.

- Budgetary constraints affect the judiciary, with an allocation between 0.08 and 0.09 percent of the GDP. Among nations, only Japan, Norway, Australia, and Iceland allocate less budget to their judiciary, and they do not confront the issue of case backlog as India does.

Proposed Reforms:

To enhance judicial productivity, the Economic Survey 2018-19 recommends:

- Increasing the number of working days.

- Establishing Indian Courts and Tribunal Services to address administrative aspects.

- Implementing technology, such as the eCourts Mission Mode Project and the phased rollout of the National Judicial Data Grid by the Ministry of Law and Justice.

Improving Case and Court Management:

- Streamlining service of notice through the National Service and Tracking of Electronic Processes (NSTEP) mobile application launched by the eCommittee of the Supreme Court.

- Embracing computerization and automation, exemplified by initiatives like the Virtual Court in Delhi, to enhance responsiveness to litigants' needs.

- Introducing Professional Court Managers, as recommended by the 13th Finance Commission, to aid in administrative functions and improve justice delivery.

Establishing Specialized Courts

- Setting up Tribunals, Fast Track Courts, and Special Courts for expedited handling of crucial cases.

- Leveraging Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) Mechanisms:

- Effectively utilizing mechanisms such as ADR, Lok Adalats, and Gram Nyayalayas for efficient dispute resolution.

Way Forward

- There should be wide introspection through extensive discussions, debates and consultations to identify the root causes of delays in our justice delivery system and providing meaningful solutions to improve the justice delivery system in India.

- Government rules, orders and regulations should be thorough and comprehensive after wide consultations with stakeholders to avoid unnecessary litigations.

- The recent passage of The Supreme Court (Number of Judges) Amendment Bill, 2019 that increased the number of Judges in the Supreme Court from 31 to 34, including the Chief Justice of India, is a welcome step.

- Speedy Justice is not only a fundamental right but also a prerequisite of maintaining the rule of law and delivering good governance. In its absence, Judicial system ends up serving the interests of the corrupt and the law-breakers.

- Judicial reforms, if taken seriously, expeditious and effective justice can see the light of day and improve India’s standing in the reports of the World Bank and other institutions and organisations that study judicial processes.

Directorate of Enforcement

The Enforcement Directorate (ED) is a versatile organization tasked with investigating offenses related to money laundering and breaches of foreign exchange laws. It operates under the Department of Revenue within the Ministry of Finance. As a leading financial investigation agency of the Indian government, the Enforcement Directorate conducts its activities in strict adherence to the Constitution and laws of India.

Historical Background of ED

- The roots of the Enforcement Directorate can be traced back to May 1, 1956, when an 'Enforcement Unit' was established within the Department of Economic Affairs to address violations of Exchange Control Laws under the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act (FERA), 1947. Initially headquartered in Delhi and led by a Legal Service Officer as the Director of Enforcement, it had branches in Bombay and Calcutta.

- In 1957, this unit underwent a name change to 'Enforcement Directorate,' and a new branch was established in Madras (now Chennai). By 1960, administrative control shifted from the Department of Economic Affairs to the Department of Revenue.

- As legislative changes occurred, the FERA, 1947, was replaced by FERA, 1973. Subsequently, with the advent of economic liberalization, FERA, 1973, a regulatory law, was repealed, giving way to the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (FEMA), effective from June 1, 2000.

- In alignment with international anti-money laundering standards, the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA) was enacted. Enforcement Directorate was entrusted with its enforcement responsibilities from July 1, 2005.

What is the Structure of ED?

- Hierarchy: The Directorate of Enforcement, with its headquarters at New Delhi, is headed by the Director of Enforcement.

- There are five regional offices at Mumbai, Chennai, Chandigarh, Kolkata and Delhi headed by Special Directors of Enforcement.

- The Directorate has 10 Zonal offices each of which is headed by a Deputy Director and 11 sub Zonal Offices each of which is headed by an Assistant Director.

- Recruitment: Recruitment of the officers is done directly and by drawing officers from other investigation agencies.

- It comprises officers of IRS (Indian Revenue Services), IPS (Indian Police Services) and IAS (Indian Administrative Services) such as Income Tax officer, Excise officer, Customs officer, and police.

- Tenure: In November 2021, the President of India promulgated two ordinances allowing the Centre to extend the tenures of the directors of the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) and the Enforcement Directorate from two years to up to five years.

- 2021 Amendment:

- It requires High-Level Committees to recommend the officers for service extensions.

- A five-member panel composed of the Central Vigilance Commissioner and Vigilance Commissioners had to recommend if an ED Director was worthy of an extension in service.

- In case of the CBI Director, a High-Level Committee of the Prime Minister, Opposition Leader and the Chief Justice of India had to recommend.

- The Delhi Special Police Establishment (DSPE) Act, 1946 (for ED) and the Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) Act, 2003 (for CV Commissioners) have been amended to give the government the power to keep the two chiefs in their posts for one year after they have completed their two-year terms.

- The chiefs of the Central agencies currently have a fixed two-year tenure, but can now be given three annual extensions.

- However, no further extension can be granted after the completion of a period of five years in total including the period mentioned in the initial appointment.

- In July 2023, The SC upheld statutory amendments which facilitate the tenures of Directors of the Central Bureau of Investigation and the ED to be stretched “piecemeal” but held illegal extension given to the outgoing ED Chief.

What are the Legal Responsibilities of ED?

The Enforcement Directorate (ED) is vested with statutory functions that involve the enforcement of the following Acts:

- COFEPOSA (Conservation of Foreign Exchange and Prevention of Smuggling Activities Act, 1974): Under COFEPOSA, the Directorate is authorized to initiate cases of preventive detention concerning violations of the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA).

- Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999 (FEMA): This civil law consolidates and amends regulations to facilitate external trade and payments, as well as to foster the organized development and maintenance of the foreign exchange market in India. The ED is tasked with investigating suspected contraventions of foreign exchange laws and regulations, adjudicating cases, and imposing penalties on those found in violation.

- Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA): Enacted in response to Financial Action Task Force (FATF) recommendations, PMLA assigns the ED the responsibility of executing its provisions. This involves investigating assets derived from the proceeds of crime, provisionally attaching properties, ensuring the prosecution of offenders, and confiscating property through Special court proceedings.

- Fugitive Economic Offenders Act, 2018 (FEOA): Introduced to address cases of economic offenders seeking refuge in foreign countries, FEOA entrusts the ED with enforcement. This law aims to discourage economic offenders from evading Indian legal processes by remaining outside the jurisdiction of Indian courts. ED is mandated under FEOA to attach properties of fugitive economic offenders who have fled India, leading to their arrest, and facilitate the confiscation of their properties by the Central Government.

How ED Functions under PMLA?

Enforcement Directorate (ED) Powers:

- The ED engages in search and seizure activities—property and monetary/documents—once it determines that money laundering has occurred, utilizing the authority granted by Section 16 (power of survey) and Section 17 (search and seizure) of the Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA).

- Following this, authorities assess the necessity of arrest as per Section 19 (power of arrest).

- Under Section 50 of the PMLA, the ED has the capability to conduct search and seizure directly without summoning the individual for questioning. There is no prerequisite to summon the person first before initiating the search and seizure.

- In case of an arrest, the ED has a 60-day window to file the prosecution complaint (chargesheet), as the penalties under PMLA do not exceed seven years.

- If only property is attached without an arrest, the prosecution complaint, along with the attachment order, must be submitted to the adjudicating authority within 60 days.

Expansion of ED's Authority under PMLA:

- The schedule of offences under the PMLA has broadened from six to 30 since 2002.

- The ED is now empowered to investigate a spectrum of crimes, encompassing terrorism, wildlife hunting, and copyright infringement.

- Amendments in 2009 introduced 'criminal conspiracy,' granting the ED the jurisdiction to investigate conspiracy cases.

- In 2015 and 2018, the ED gained the authority to seize Indian properties linked to laundered money acquired abroad.

- In 2019, amendments extended the ED's powers to attach properties acquired through criminal activity.

- In April 2023, the Ministry of Finance expanded the scope of PMLA to include activities related to Virtual Digital Assets (VDA) and cryptocurrency.

- In July 2023, the Goods and Services Tax Network (GSTN) was incorporated into the PMLA, facilitating information sharing between GSTN, ED, and other agencies by modifying Section 66 provisions.

Comparison of ED, CBI, and NIA Powers:

- PMLA grants the ED the authority to take cognizance of offences across the country without the consent of state governments, allowing it to register money laundering cases based on FIRs filed by state police forces. This stands in contrast to the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI), which requires state government consent or court/Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) orders.

- While the National Investigation Agency (NIA) has the power to take suo motu cognizance of offences nationwide, its schedule of offences is limited compared to the PMLA.

Contentious Provision:

- The admissibility of statements made by the accused as evidence and the stringent bail provisions within the PMLA have been contentious. Notably, the PMLA is the only act in the country where statements recorded before an investigating officer are admissible as evidence, a feature absent in repealed laws such as TADA and POTA. The provision for bail was struck down by the Supreme Court, as it presupposed trial at the bail stage itself.

What about ED’s Jurisdiction?

- Both FEMA or PMLA apply to the whole of India. So, the ED can take action against any person on which this act applies.

- Cases under FEMA may lie in civil courts where PMLA cases will lie in criminal courts.

- The agency has jurisdiction over a person or any other legal entity who commits a crime.

- All the public servants come under the jurisdiction of the agency if they are involved in any offence related to money laundering.

- ED can not take an action suo motu. One has to complain to any other agency or Police first and then ED will investigate the matter and will identify the accused.

- The ED will investigate the matter and may attach the property of an accused person and also make an arrest and start proceeding with the violation of the provisions of FEMA and PMLA act.

- The matter will be resolved by way of adjudication by courts or PMLA courts.

Why is the ED being Criticised Lately?

- The Supreme Court (SC) is examining allegations of rampant misuse of PMLA by the government and the Enforcement Directorate (ED). Major Allegations include:

- Being Used for Ordinary Crimes:

- PMLA is pulled into the investigation of even “ordinary” crimes and assets of genuine victims have been attached.

- PMLA was a comprehensive penal statute to counter the threat of money laundering, specifically stemming from trade in narcotics.

- Currently, the offences in the schedule of the Act are extremely overbroad, and in several cases, have absolutely no relation to either narcotics or organised crime.

Lack of Transparency and Clarity:

- The Enforcement Case Information Report (ECIR) - an equivalent of the FIR - is considered an “internal document” and not given to the accused.

- The ED treats itself as an exception to the principles and practises [of criminal procedure law] and chooses to register an ECIR on its own whims and fancies on its own file.

- There is also a lack of clarity about ED’s selection of cases to investigate.

- The initiation of an investigation by the ED has consequences which have the potential of curtailing the liberty of an individual.

What are the Recent Controversies Regarding PMLA and the Powers and Efficiency of ED?

- The Prevention of Money Laundering Act (PMLA), established in 2002, has undergone significant modifications over time to empower itself in addressing the issue of money laundering.

- Nevertheless, these amendments have prompted numerous petitions across the country, challenging the extensive powers conferred upon the Enforcement Directorate (ED) under PMLA for actions such as searching, seizing, investigating, and attaching assets believed to be proceeds of crimes.

- In a recent judicial proceeding, the Supreme Court affirmed the constitutional validity of both the PMLA and ED's authority to conduct inquiries, make arrests, and attach property, as outlined in Section 5 of the Act.

- The Court emphasized that Section 5 establishes a balanced framework to safeguard the interests of individuals while ensuring that the proceeds of crime remain accessible for treatment in accordance with the 2002 Act.

- The argument that ED authorities are akin to police officers, and therefore, statements recorded by them (as per Section 50 of the Act) violate Article 20(3) of the Indian Constitution, which prohibits self-incrimination, was rejected by the Court.

- Despite thousands of cases being registered and numerous individuals being arrested, the ED's conviction rate under PMLA remains notably low. Government data presented in the Indian Parliament indicated zero convictions between 2005 and 2013-14, and from 2014-15 to 2021-22, only 23 out of 888 cases resulted in convictions.

Proposed Reforms for the ED:

- While the law has bestowed formidable powers upon the ED to handle accused individuals, there is a legitimate concern about the potential for political misuse.

- A consensus between the adjudicating authority and ED officers is essential to ensure adherence to the constitutionality of provisions under PMLA, promoting transparent investigations and preventing the process itself from becoming punitive.

- The augmented powers of the ED should be coupled with a stronger commitment to swiftly resolve cases, fostering expeditious trials and convictions for the benefit of both the judiciary and enforcement agencies.

- Continuous scrutiny of the Enforcement Directorate's operations is necessary to assess whether the clarified legal framework will enhance the current conviction rate, which presently stands at less than half a percent. Any identified gaps in the operational aspects can be addressed through suitable legislation, executive action, or revised court orders, aligning with the dynamic nature of legal evolution.

The Multi-State Cooperative Societies (Amendment) Bill 2023

The Lok Sabha has approved the Multi-State Cooperative Societies (Amendment) Bill 2023, aiming to make amendments to the Multi-State Co-operative Societies Act of 2002.

Cooperative Societies in India

- Cooperatives are organizations that operate on a voluntary, democratic, and autonomous basis, with members actively involved in formulating policies and making decisions.

- Following independence, the initial five-year plan (1951-56) highlighted the significance of incorporating cooperatives to address diverse facets of community development.

- As per Article 43B (Directive Principles of State Policy) of the Indian Constitution, introduced by the 97th Amendment in 2011, states are mandated to promote -

- The voluntary establishment,

- Autonomous operations,

- Democratic oversight, and

- Professional management of cooperative societies.

What are Multi-state Co-operative Societies?

- These are societies that have operations in more than one state. For example, a farmer-producers organisation (FPO) which procures grains from farmers from multiple States.

- The Multi-State Co-operative Societies Act 2002 provides for the formation and functioning of multi-state co-operatives.

- According to the Supreme Court of India, Part IXB - The Co-operative Societies (also inserted by the 97th Amendment), will only be applicable to multi-state co-operative societies, as states have the jurisdiction to legislate over state co-operative societies.

Shortcomings with respect to the Functioning of Co-operatives:

- Inadequacies in governance.

- Politicisation and excessive role of the government.

- Inability to ensure active membership.

- Lack of efforts for capital formation.

- Inability to attract and retain competent professionals.

- There have also been cases where elections to co-operative boards have been postponed indefinitely.

Key Provisions of the Multi-State Cooperative Societies (Amendment) Bill 2023:

Election of Board Members:

- The existing practice under the Act involves the board of a multi-state cooperative society conducting elections. The Bill introduces a modification, specifying that the Co-operative Election Authority, established by the central government, will now oversee such elections.

- This Authority comprises a chairperson, vice-chairperson, and up to three members appointed by the central government based on the recommendations of a selection committee.

Amalgamation of Cooperative Societies:

- While the Act allows the amalgamation and division of multi-state cooperative societies through a general meeting resolution with at least two-thirds of the members present and voting, the Bill permits state cooperative societies to merge into an existing multi-state cooperative society, subject to the applicable state laws.

Fund for Ailing Cooperative Societies:

- The Bill introduces the Co-operative Rehabilitation, Reconstruction, and Development Fund to revive financially struggling multi-state cooperative societies.

- This fund will be financed by multi-state cooperative societies that have reported profits in the preceding three financial years.

Restriction on Redemption of Government Shareholding:

- The Act allows for the redemption of shares held in a multi-state cooperative society by certain government authorities, based on the society's bye-laws.

- The Bill amends this provision, stipulating that shares held by the central and state governments cannot be redeemed without their prior approval.

Redressal of Complaints:

- Under the Bill, the central government will appoint one or more Co-operative Ombudsmen with specific territorial jurisdictions. The Ombudsman is required to complete the inquiry and adjudication process within three months of receiving a complaint.

- Any appeals against the Ombudsman's directions can be filed with the Central Registrar, appointed by the central government, within one month.

Significance of the Bill

- It will strengthen cooperatives by making them transparent and introducing a system of regular elections.

- The Bill seeks to align its provisions with those provided under Part IXB of the Constitution and address concerns with the functioning and governance of co-operative societies.

Concerns regarding the Provisions of the Bill:

- Effectively imposes a cost on well-functioning societies: Sick multi-state co-operative societies will be revived by a Fund that will be financed through contributions by profitable multi-state co-operative societies.

- Against the co-operative principles of autonomy and independence: Giving the government the power to restrict redemption of its shareholding in multi-state co-operative societies.

The Cinematograph (Amendment) Bill 2023

The Cinematograph (Amendment) Bill 2023, aimed at combatting film piracy and altering the certification process for movies by the censor board, has been approved by the Rajya Sabha.

The background

- The Cinematograph (Amendment) Bill of 2019 was presented in the Rajya Sabha, primarily addressing film piracy. It underwent examination by the Standing Committee on Information Technology, which suggested incorporating age-based certification categories.

- Subsequent versions, including the revised Cinematograph (Amendment) Bill of 2021 and the final iteration in 2023, were formulated through consultations with industry stakeholders and public input.

Details of the 2023 Bill:

- Proposed by the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (I&B), the bill aims to amend the Cinematograph Act of 1952.

- This original act grants the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) the authority to mandate edits in films and approve them for screening in theaters and on television, or reject their exhibition altogether.

Why does the Cinematograph Act 1952 need amendments?

- To harmonise the law with various executive orders, SC judgements, and other legislations like the Copyright Act, 1957 and the IT Act (IT) 2000.

- To improve the procedure for licensing films for public exhibition by the CBFC, and

- To expand the scope of categorisations for certification.

- To curb the menace of piracy, there was a huge demand from the film industry to address the issue of unauthorised recording and exhibition of films, which is causing them huge losses (Rs 20,000 crore annually).

Significance of the Bill:

- It will make the certification process more effective, in tune with the present times.

- By comprehensively curbing the menace of film piracy, it will help in faster growth of the film industry and boost job creation in the sector.

Concerns:

- OTT platforms out of the purview of the Bill: What if an uncut movie is broadcast on OTT?

- Age-appropriate categories are self-regulatory: It places the onus on parents and guardians to determine if the material is appropriate for viewers of a particular age range.

|

63 videos|5408 docs|1146 tests

|