Post-Mauryan Period: Contact with Outside World | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Trade and Traders |

|

| Long-Distance Trade in Ancient India |

|

| Trade with East and South-East Asia |

|

| Indo-Roman Trade |

|

| The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea |

|

Trade and Traders

The period around 300 BCE to 300 CE witnessed a significant expansion of trade activity, both within the Indian subcontinent and with other lands. This era marked the transition from barter to a more sophisticated money economy, facilitated by the widespread use of coins.

Money Economy:

- Trade was greatly aided by the expansion of the money economy. The issuing of small denominational coins by the Kushanas and Satavahanas made coins a common medium for small-scale transactions.

- Literary works from this period refer to different types of coins, including:

- Dinara: A gold coin.

- Purana: A silver coin.

- Karshapana: A copper coin.

- In the far south of India, various coins were used, including northern coins, locally made punch-marked coins, and Roman denarii. There is also evidence of die-struck coins issued by local kings such as the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas.

- Most ancient Indian coins were issued by the state, although there were some instances of city coins and guild coins.

- Barter and the use of cowrie shells(a shell found in the waters off the Maldives) as a unit of exchange continued alongside money-based transactions.

The Dharmashastra Texts:

- The Dharmashastra texts provide various prescriptions regarding trade, such as taxes,profits, and interest rates on loans.

- For example, the Yajnavalkya Smriti advises the king to set prices with a 5% profit margin on indigenous goods and 10% on foreign goods, considering the interests of both consumers and merchants.

- The Manu Smriti suggests that traders should be taxed on their profits rather than their capital outlay, proposing a 5% tax rate.

- The texts also prescribe punishments for adulteration,cheating, and fraud, and suggest high-interest rates varying by risk and the varna (social class) of the borrower.

The Jatakas:

- The Jatakas provide accounts of long caravan journeys, describing various modes of transport such as foot travel,bullock carts,chariots, and palanquins.

- They mention the presence of wells,tanks, and rest houses along the roads, as well as the closing of city gates at night for security.

- Partnerships among merchants are also referenced in these texts.

Sangam Texts:

- The Sangam texts offer vivid descriptions of markets and traders in Tamilakam.

- Markets in cities like Puhar and Madurai are depicted, showcasing sellers of various goods such as flowers,garlands,jewellery,cloth, and bronze.

- Caravans of itinerant traders carrying goods like

- paddy

- salt

- pepper

- to and from interior regions are described, highlighting the challenges faced by salt traders.

- The texts also mention the paravatar, coastal inhabitants who transitioned from fishing and salt-making to long-distance trade and pearl diving.

- Trade routes included the Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha, with connections to various regions and important trade termini.

- Coastal trade became significant, with ports on the eastern coast playing a crucial role in maritime trade with the Mediterranean.

Famous Merchandise Cities:

- Different cities were known for specific merchandise, such as silk,fine muslin, and sandalwood from Varanasi,red blankets from Gandhara,woollen textiles from the Punjab, and cotton textiles from Kashi.

- Textiles from the south, particularly from Kanchi and Madurai, were also highly regarded.

Trade Routes

- The ancient trade routes, such as the Uttarapatha and Dakshinapatha, were crucial for trade.

- The Uttarapatha connected Taxila in the northwest with Tamralipti in the Ganga delta.

- Other important routes included:

- Sea route connecting Sindh and Gujarat.

- Route from Rajasthan to the Deccan, following the Aravalli foothills.

- Route from Mathura to Ujjain in Malwa, and then to Mahishmati in the Narmada valley.

- From Mahishmati, routes crossed the Western Ghats to Surat or into the Deccan.

- Routes connecting Ujjayini in Malwa with coastal towns like Bharukachchha and Supparaka.

- Route from Kaushambi to Vidisha in eastern Malwa.

- South Indian routes followed rivers, connecting places like Manmad and Masulipatam,Pune and Kanchipuram,Goa and Tanjavur, and Keral and Cholamandala.

- Important trade termini included:

- Pushkalavati in the northwest.

- Patala and Bhrigukachchha in the west.

- Tamralipti in the east.

- Western India had market towns like Paithana(Paithan),Tagara(Ter),Suppara(So-para), and Calliena(Kalyan).

- Boats from the sea traveled up the Ganga to Pataliputra, facilitating trade.

- Port of Muziris(Muchiri) was significant for coastal trade.

- Trade items included cotton textiles,steel weapons,horses,camels,elephants, and pepper.

- Cities were famous for specific merchandise, such as silk,muslin,sandalwood,red blankets,woollen textiles, and cotton textiles.

- Archaeological evidence from different sites provides detailed information about the goods involved in trade during this period.

Long-Distance Trade in Ancient India

The Indian subcontinent has been a part of a larger Indian Ocean world since ancient times. Scholar H. P. Ray advocates for a wider perspective on maritime history, focusing on the social practices involved in maritime technology. This approach encompasses not just commodities and trade routes but also aspects like boat building, sailing techniques, shipping organization, and the roles of fishing, sailing communities, and traders. It emphasizes the connections between maritime activities and the broader political, economic, social, religious, and cultural history.

During the period of around 200 BCE to 300 CE, long-distance trade thrived, as evidenced by various texts and archaeological findings.

Marine Archaeology:

- Marine archaeology has uncovered significant evidence of ancient coastal cities that have been submerged by the sea.Excavations at Dwarka and Bet Dwarka off the coast of Gujarat have revealed the remains of structures, stone images, objects made of copper, bronze, and brass, iron anchors, and a wrecked boat dating back to around 200 BCE to 200 CE. These sites were clearly oriented towards maritime trade.

The Jatakas:

- The Jatakas, ancient Indian texts, describe long-distance journeys undertaken by Indian traders over land, river, and sea. They mention Indian traders venturing into distant lands such as Suvarnadvipa (Southeast Asia),Ratnadvipa (Sri Lanka), and Baveru (Babylon).

- The texts also reference various ports on the Indian coasts, including Bharukachchha,Supparaka, and Suvara on the western coast, and Karambiya,Gambhira, and Seriva on the eastern coast.

- Stories of voyages, challenging journeys, and shipwrecks are prevalent in the Jatakas. They also mention sailors organized into guilds, with the head of the guild known as the niyamakjettha.

Sangam Texts:

- The Sangam texts, ancient Tamil literature, depict the arrival of yavanas (foreign traders) bringing goods by ship into the ports of South India. The ports along the Coromandel coast were particularly significant for trade with Southeast Asia.

- Kaveripattinam, a prominent port mentioned in the Sangam poems, was known for its diverse merchant community speaking various languages. Another port, Perimula (or Perimuda), located at the mouth of the Vaigai River near Rameswaram, is noted for excavations revealing Roman pottery, coins, and locally made imitations of Roman pottery and coins.

Stimulus of Trade

- The demand for Chinese silk in the Mediterranean region significantly stimulated trans-regional and trans-continental trade during this period.

- The arrival of Central Asian peoples facilitated close contacts between Central Asia and India.

- The Kushana Empire played a crucial role in trade by encompassing key sections of the silk routes and providing a degree of safety for traders, along with reducing tariff posts.

- India received substantial gold from the Altai mountains in Central Asia and possibly through trade with the Roman Empire. The Kushanas were the first rulers in India to widely issue gold coins.

- The maritime route from the western coast of India to the Persian Gulf, known since proto-historic times, gained importance in the early centuries CE as traders began utilizing the southwest monsoon winds for sailing across the Indian Ocean.

- The crew of a large ship typically included a captain (shasaka),pilot (niryamaka), a person responsible for manipulating the cutter and ropes, and a bailer of water.

- Similar to other ancient mariners, Indian sailors used special birds to locate land. When released from the ship, these birds would fly towards land if it was nearby; otherwise, they would return to the ship.

- Ancient Greeks noted differences between Indian boats and those from Mediterranean regions. Onesicritus, in Strabo’s account, remarked on the Indian boats' construction and inferior sails, while Pliny mentioned their construction but deemed them suited to the seas they sailed on.

- Indian boats were distinctive for their planks being stitched together with coir rope rather than held with nails. Sewn boats were likely considered better for withstanding strong waves and impacts with the shore.

- Besides Chinese silk, various other commodities were involved in the vibrant trade interactions and networks connecting the Indian subcontinent with Central Asia, West Asia, China, Southeast Asia, and Mediterranean Europe. The vast distances involved in transporting some goods indicate that these trade networks included numerous groups of traders from different regions.

Trade with East and South-East Asia

The period around 200 BCE to 300 CE witnessed a significant increase in trade contacts between the Indian subcontinent and East and Southeast Asia.

Trade with China

- The region around Gandhara, due to its closeness to Central Asia and the presence of Chinese military garrisons in the Pamirs, attracted the interest of the Han emperors of China.

- Initially, the focus was on military and political interests, but soon shifted to trade and religious exchanges with the Indian subcontinent.

- Silk became the dominant item of trade.

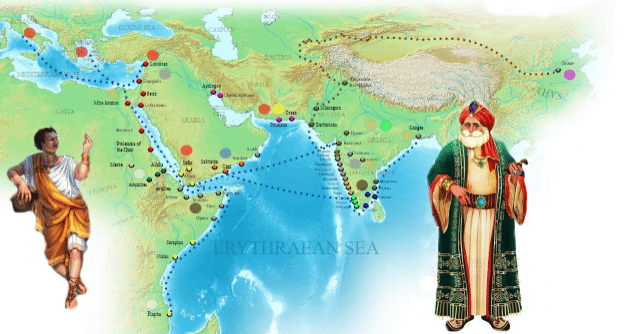

The Great Chinese Silk Route:

The Silk Route linked India with Central Asia,West Asia, and Europe.

- The route spanned approximately 4,350 miles, starting from Loyang on the Yellow River in China and ending at Ctesiphon on the Tigris River in West Asia.

- From Loyang, the route passed through Ch'ang and Tunhuang, near the source of the Yellow River.

Route Details:

Northern Route

- Passed through oases between the northern edge of the Takla Makan Desert and the Tienshan Mountains.

- Connected to the Caspian Sea, serving as the main route to Persia.

Southern Route

- Traveled along the southern edge of the desert and the Kunlun Mountains.

- Passed through Bactria(northern Afghanistan) and joined the northern route at Merv in Turkmenistan.

Kashgar

- At Kashgar, the two routes merged before splitting again into the northern and southern routes.

Trade Connections:

- From Afghanistan, a route led through the Kabul Valley to northwestern cities of the subcontinent, such as Purushapura,Pushkalavati, and Taxila, and further inland cities.

- Another route from Kashgar ran through Gilgit in Kashmir.

- North-west India became a vital junction for trade between China and the Roman Empire.

Trade Goods:

- Frankincense and styrax were fragrances obtained by the Chinese from Central Asia and exported westward.

- Superior animal hides were among the Central Asian products.

- Important items transported from or through India to China included pearls,coral,glass, and fragrances.

- Silk was the major Chinese export to India.

The Kushan Empire:

Control of the Silk Route

- The Kushans governed the Silk Route, which extended from China through their empire in Central Asia and Afghanistan to Iran and Western Asia.

- This route generated substantial income for the Kushans, allowing them to build a prosperous empire by collecting tolls from traders.

Disturbance in Trade:

- Trade between China and the West faced interruptions in the 3rd and 4th centuries due to political factors. After the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 CE, China became fragmented.

- This period also saw the breakup of the Byzantine Empire from Rome and the collapse of the Kushan Empire. Some cities along the Oxus River became deserted during this time.

However, trade between China and India persisted, albeit with changes in trade routes.

Trade with Southeast Asia

Historically, Indian scholars viewed India’s interactions with Southeast Asia primarily through the lens of political and cultural colonization. However, more recent evaluations have examined the reciprocal relationships between India and Southeast Asia from a more objective and long-term perspective.Literary Evidence:

- Ancient Sanskrit and Pali texts mention a land called Suvarnadvipa or Suvarnabhumi, associated with wealth and riches, often identified with Southeast Asia.

- The Arthashastra mentions incense called kaleyaka from Suvarnabhumi and aloeswood from beyond the sea.

- The Milindapanha also refers to Suvarnabhumi in relation to shipping ports.

- Jataka tales describe sea voyages from Varanasi and Bharukachchha to this land.

Archaeological Evidence:

- Archaeological findings indicate maritime links between India and both coastal and inland Southeast Asia from around 500/400 BCE onwards.

- Indian artifacts, primarily beads of colored glass, faceted carnelian, and etched agate, have been discovered at metal age sites in contexts dated from 500 BCE to 1500 CE.

- Etched carnelian beads have been found in burials in west-central Thailand and through excavations in Malaysia.

- Glass beads of various shapes and colors, some of South Indian origin, have been found at Southeast Asian sites dating from 300 BCE to the 17th century CE.

- In the 1st century CE, there was a notable increase in the quantity and variety of Indian items exported to Southeast Asia, coinciding with the emergence of kingdoms in mainland Southeast Asia, a more stratified society, expanded craft production, and increased inter-regional trade.

- Indian artifacts have been found in iron age burials in the Malay peninsula and on the southeast coast of Thailand, as well as in emerging urban centers in the valleys of the Chao Phraya,Irrawaddy, and Mekong rivers.

- As coinage was not present in Southeast Asia until the mid-1st millennium BCE, trade with India likely occurred through barter or the use of cowrie shells.

Traded Items:

Exports from Southeast Asia to India:

- Gold

- Spices such as cinnamon and cloves

- Aromatics

- Sandalwood

- Camphor

Some of these items were further shipped to Western markets from India due to demand in the Mediterranean region.

Exports from India to Southeast Asia:

- Cotton cloth

- Sugar

- Beads

- Certain types of pottery

- Possibly tin from the Malay peninsula

The trade was not limited to luxury goods.

Changes in International Trade Patterns in the 3rd and 4th Centuries:

- Long-distance trade networks fragmented into regional and local circuits.

- Roman trade interests shifted southward.

- Trade between India and West Asia expanded.

- Ports in Sri Lanka gained prominence with the establishment of a direct route between Sri Lanka and China.

Indo-Roman Trade

References of Yavanas:

- The term yavana originally referred to the Greeks in ancient Indian texts but later came to denote all foreigners from the west of the subcontinent.

- In Ashoka's inscriptions, the yavanas are described as people living on the northwestern borders of the Maurya empire.

- Between 200 BCE and 300 CE, yavanas were seen as 'westerners' involved in trade.

- Early Tamil literature frequently mentions yavanas:

- Sangam poems describe their large ships on the Periyar river, bringing gold and wine, and taking away black pepper.

- One poem compares the noise of weavers in Madurai to the sound of workers loading and unloading goods onto yavana ships at midnight.

- A poem by Nakkirar talks about the Pandya king Nanmaran drinking perfumed wine brought by the yavanas.

The period between the 2nd century BCE and the 2nd century CE saw flourishing trade between India and the Roman Empire.

- The Kushans and the Satvahanas especially benefited from their trade with the Roman Empire. The balance of trade was generally favorable to India.

- In addition to exporting goods to the Mediterranean, India played a crucial role in the Chinese silk trade.

- During the time of Roman Emperor Augustus (27 BCE–14 CE), traders began to avoid the section of the Silk Route passing through Parthian central Asia due to its turbulent conditions.

- Part of the trade was redirected overland to India and then onwards from Indian ports to the Roman Empire via the sea route.

- Chinese silk also reached Europe via India, as obstacles were placed by the Parthian rulers of Iran.

- This trade declined after the time of Marcus Aurelius in the late 2nd century BCE, partly due to internal issues within the Roman Empire. However, it did not come to a complete end.

- The Periplus provides a list of goods exported from Indian ports on the Indus delta and the Gujarat coast to the Roman Empire.

- Pliny and Dio Chrysostom mention the significant outflow of Roman gold into India.

- The Vienna Papyrus, recording a business deal between shippers from Alexandria and Muchiri, refers to a loan for acquiring goods like nard (aromatic balsam), ivory, and textiles.

Discovery of Roman coins:

- The discovery of a large number of Roman coins in India, comprising nearly 170 finds from about 130 sites, provides significant evidence of the Indo-Roman trade.

- Most of these coins belong to the reigns of emperors Augustus (31 BCE–14 CE) and Tiberius (14–37 CE), with some imitations of these coins also found.

There are two main types of Roman coins found in India:

- Denarii– silver coins

- Aurei– gold coins

The silver coins are more numerous in both Rome and India.

South India:

- In South India, there is a concentration of Roman coin finds in the Coimbatore area of Tamil Nadu and the Krishna valley in Andhra Pradesh.

West India:

- In West India, Roman coins have been found at sites such as near Sholapur,Waghoda,Vadgaon-Madhavpur, and Kondapur, but they are relatively few in number.

North India:

- In North India, apart from a few finds at sites like Taxila,Manikyala, and Mathura, hardly any Roman coins have been discovered.

- The Kushan rulers, influenced by their connections with Rome, issued new coins resembling the Roman dinar. However, these coins were not used in everyday transactions, which were conducted with coins made of glass, copper, and potin.

- While the Kushanas might have melted down and re-minted Roman gold coins, this does not explain the lack of silver coins in the north.

East India:

- In East India, only one hoard of gold aurei has been reported, found in Singhbhum.

- Some Roman coins in India bear slash marks and small countermarks such as dots, stars, and curves, possibly indicating ownership marks.

- In regions with established currency systems, such as the Kushana and Satavahana kingdoms, Roman coins may have been melted down for bullion.

- In the eastern Deccan, where indigenous currency systems were weaker, Roman coins may have been used as currency.

- Roman coins reached India well after the reigns of the emperors who issued them.

- Roman copper coins have been found in Gujarat from the second half of the 3rd century CE.

- Roman bronze coins are discovered at various sites in India, mostly in Tamil Nadu, dating from the latter half of the 4th century CE. Thousands of these coins have also been found in Sri Lanka, indicating a southward shift in maritime networks.

Discovery of Roman Potteries:

In addition to coins, valuable information about Indo-Mediterranean contacts comes from the discovery of Roman pottery in India.

The two types of Roman pottery found in India are:

- Amphorae jars

- Terra sigillata

Amphorae

- Amphorae are jars with a large oval body, a narrow cylindrical neck, and two handles.

Terra sigillata

- Terra sigillata is red glazed pottery, decorated by pressing into a mold.

- It includes molded, decorated wares as well as undecorated, wheel-made ones made in Italy or imitations thereof.

Rouletted ware and Red polished ware:

- Rouletted ware is pottery with a smooth surface and usually a metallic luster, featuring concentric bands of rouletted designs.

- Initially thought to be foreign ware, it is now considered locally produced.

- Red polished ware, found at many sites in Gujarat, was also once considered foreign but is now believed to have been locally made.

Arikamedu:

- Arikamedu, near Pondicherry, provides significant evidence of India's maritime trade links.

- Excavations reveal an occupation spanning from the end of the 1st century BCE to the 1st and 2nd centuries CE.

- A brick structure identified as a warehouse, along with two walled courtyards associated with tanks and drains, suggest the presence of dying vats for muslin cloth prepared for export.

- While locally produced pottery was found, Mediterranean wares such as amphorae and arretine ware (Terra sigillata) were also present.

- Other finds include over 200 beads of shell, bone, gold, terracotta, and semi-precious stones, a Graeco-Roman gem possibly depicting Emperor Augustus, and a fragment of a Roman lamp made of fine red ware.

- Based on these discoveries, Mortimer Wheeler concluded that Arikamedu was Poduke, one of the yavana emporia mentioned in classical accounts.

Roman pottery found at other places:

- Besides Arikamedu, Mediterranean amphorae and terra sigillata have been found at other southern sites such as Uraiyur,Kanchipuram, and Vasavasamudram.

- These pottery pieces have also been discovered at sites in Gujarat and western India, including Dwarka,Prabhas Patan,Ajabpura,Sathod,Jalat, and Nagara.

Discoveries of other Roman objects:

- Other objects of possible Roman origin, such as terracotta objects, glassware, metal artifacts, and jewelry, have been reported. However, many of these seem to be imitations of Roman objects.

- Clay bullae made in clay molds imitating Roman coins are common throughout the subcontinent. These bullae, often with a loop or perforation, were likely worn around the neck.

- Brahmapuri, in the western part of Kolhapur town(Maharashtra), yielded a large hoard of 'Roman' bronzes, including a statuette of Poseidon, the Roman sea god.

- The distribution pattern of Roman artifacts in India indicates that while trade was initially concentrated on the western coast, the Coromandel coast soon became more important.

- Excavations at Berenike on the Egyptian coast, yielding black pepper and beads of South Indian and Sri Lankan manufacture in a 4th century CE context, reflect the flourishing East-West trade.

- Indo-Roman trade was not a direct exchange between Indians and Romans but involved the participation of middlemen from various regions, including Arabs and Greeks of Egypt.

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

- Ancient Greek and Roman geographers referred to the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and the Persian Gulf as the Erythraean Sea. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is a unique handbook, written in Greek by an unknown writer of Egypt for traders involved in mercantile activity between Egypt, east Africa, southern Arabia, and India. The book must have been useful for traders in ancient times; it also offers historians a very useful source of detailed information on trade in the Indian Ocean.

- Certain references in the text and the level of detail indicate that the author wrote from personal experience, not from hearsay. He was evidently a merchant writing for the benefit of other merchants. His book gives details of sailing schedules, routes, trade, ports, and merchandise. The author also threw in information about rulers whose control extended over the ports. He was a curious and observant man and added many remarks on flora and fauna and on the appearance, life, and customs of people of different lands. One thing that he does not say much about is religion.

The Periplus describes trade conducted along two main routes starting from the Red Sea ports of Egypt

One route went along the African coast, and the other to India. There are references to other routes as well. The wealth of detail in the book has enabled historians to draw up an inventory of items traded at various ports involved in Indian Ocean trade networks in the early centuries CE.

The wider roles of Trade and Traders:

- Merchants appear as donors in inscriptions from different parts of the subcontinent in this period. The increasing affluence of sections of the merchant community coincided with religious institutions getting more institutionalized and organized. Patronizing such institutions by extending financial support was simultaneously an expression of devotion and piety as well as a quest for the validation of social status.

Seafaring merchants:

- Seafaring merchants can be identified in sculptures at several religious establishments.

- For instance, a railing medallion from Bharhut depicts a huge sea monster on the verge of swallowing a boat and its crew.

- An inscription suggests that this was a scene depicting the Jataka story of the merchant Vasugupta, who was saved from disaster by meditating on the Buddha.

- A Mathura sculpture depicts a bodhisattva in the form of a horse saving shipwrecked sailors from ravenous yakshis.

- A more graphic reflection of the perils faced by mortal seafarers are the hero stones found on the Konkan coast, sculpted with scenes of sea battles, set up by survivors in honour of those who had lost their lives.

Relationship between Buddhist monasteries, traders, and guilds

- A close relationship soon developed between Buddhist monasteries, traders, and guilds.

- As monasteries expanded and received more gifts, they were forced to get involved in various kinds of financial activities, and this led to the forging of a reciprocal relationship between monks and traders.

- Passing traders provided donations to monasteries, and monasteries in turn provided services for traders.

For example:

- The residue of what may be wine sedimentation (or medicine) was found in amphorae sherds at the monastic site of Devnimori in Gujarat.

- In Pushkalavati, a workshop or storeroom of what appears to be a liquor distillation apparatus was found in a Buddhist monastery.

- The evidence from these two sites shows that Buddhist monks may be engaged in liquor trade.

- They may also have traded in items such as incense and precious stones, which may have been used for liturgical purposes.

However, the evidence of direct links between Buddhist monasteries and trade is not on the whole very substantial. The location of monasteries along trade routes does not in itself constitute conclusive evidence.

The hypothesis of the connections between Buddhist monasteries and guilds in ancient India seems to be based more on analogies with patterns that emerged in East Asia in a later period.

Cultural impact of trade

- There is a connection between long-distance trade, urbanization, developments in Buddhist theology, and the spread of Buddhism in China.

- The demand for relics, images, and ceremonial objects played an important sustaining role in Sino-Indian trade.

- Attention may be directed to possible Buddhist symbols and legends on coinage, seals, and pottery, and to the emergence of the idea of the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara as the saviour of travellers and seafarers.

- It is argued that trade networks between the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia were initially dominated by trading groups owing allegiance to Buddhism and that Buddhism spread to Southeast Asia through trading channels.

- However, while trade was an important vehicle of cultural transmission, there were other agents as well.

- The activities of Chinese and Indian monks are an important part of the story of the spread of Buddhism to China.

- And the fact that rituals in Southeast Asian courts were dominated (as in India) by Brahmanical practices points to the presence of Brahmana ritual specialists in those courts.

|

347 videos|975 docs

|

FAQs on Post-Mauryan Period: Contact with Outside World - History Optional for UPSC

| 1. What were the major trade routes used for long-distance trade in ancient India? |  |

| 2. How did ancient India engage in trade with East and Southeast Asia? |  |

| 3. What role did the Indo-Roman trade play in ancient Indian commerce? |  |

| 4. What is the significance of the "Periplus of the Erythraean Sea" in understanding ancient trade? |  |

| 5. How did the post-Mauryan period influence India's contact with the outside world? |  |