NCERT Summary: Theme-14 Politics, Memories, Experiences (Class 12) | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

The Partition of British India in 1947, which led to the creation of India and Pakistan, was a deeply traumatic event marked by violence, displacement, and loss. While the independence from colonial rule was a moment of joy, it was overshadowed by the brutal realities of Partition. Millions were uprooted, becoming refugees and forced to rebuild their lives from scratch in unfamiliar lands.

This chapter aims to explore the history of Partition, delving into the reasons and processes behind it, as well as the harrowing experiences of ordinary people during the period from 1946 to 1950 and beyond.

It will also discuss the method of oral history, which involves reconstructing the past by talking to people and interviewing them. Oral history has its strengths and limitations:

- It can provide insights into aspects of society's past that are not well-documented in other sources.

- However, there are many topics where oral accounts may not offer much information, and we would need to rely on other materials to build the history.

The chapter will return to this issue later, highlighting the value and challenges of using oral history to understand the experiences during and after the Partition.

Some Partition Experiences

Here are three incidents narrated by people who experienced those trying times to a researcher in 1993. The informants were Pakistanis, the researcher Indian. The job of this researcher was to understand how those who had lived more or less harmoniously for generations inflicted so much violence on each other in 1947.

A Young Man's Escape

- A young man, a member of a Hindu family, was fleeing from a violent mob in August 1947. His family had been attacked, and he was the only survivor.

- As he ran, he encountered an elderly Hindu woman who offered to help him. She suggested that he pretend to be dead and lie among the bodies piled up by the attackers.

- The woman explained that this would save his life, as the attackers were looking for any surviving Hindus to kill.

- Following her advice, the young man lay down among the dead and managed to escape the mob.

A Father's Determination

- A father and his son were trying to escape from a violent mob targeting their Hindu community. The father had a plan to save their lives by disguising themselves among the dead bodies.

- They found a suitable spot where the bodies were piled up and began their grim act. The father lay down on the ground, and the old lady who had helped them earlier started placing dead bodies on him.

- As they were doing this, a group of armed Hindu men arrived at the scene, looking for survivors. They started searching through the bodies for any signs of life.

- One of the men spotted the father's wristwatch and mistakenly thought it was a sign of life. He began to interrogate the father, asking him questions about his identity and religion.

- The father managed to convince the men that he was a Hindu and that he had been hiding from the mob. He explained that he had lost his family and was trying to survive.

- The armed men eventually accepted his story and allowed him and his son to leave.

A Host's Hospitality

- The manager of a youth hostel in Lahore in the early 1950s described an incident where he encountered a young Indian man looking for accommodation.

- The manager initially refused to give the young man a room, citing his Indian nationality. However, he offered him tea and a story instead.

- The young man explained that he was in Pakistan to deliver a message to his friend, who had moved to Delhi. He was trying to find a way to reach his friend and deliver the message.

- The manager, intrigued by the young man's story, decided to help him. He offered him a place to stay and promised to assist him in finding a way to reach his friend.

- The incident highlighted the complexities of identity and hospitality in post-Partition Pakistan, where people from different backgrounds were trying to navigate their new realities.

The Researcher's Experience: A Glimpse into Partition

- In the early 1990s, a researcher visited the History Department Library of Punjab University in Lahore to gather information about the Partition of India in 1947.

- The librarian, Abdul Latif, was exceptionally helpful and provided the researcher with relevant materials, including photographs related to the historical events of that time.

- During the visit, the researcher came across a document that detailed the experiences of a young man during the Partition. The document described how the young man, a Muslim, had to navigate the chaos and violence that erupted during the divide.

- The researcher was struck by the vivid accounts of individuals who faced immense challenges during the Partition. One particular story stood out, where a young boy's life was saved by a kind stranger amidst the turmoil.

- The photographs and documents collected during the visit provided a deeper understanding of the complexities and human experiences during the Partition era.

A Momentous Marker

Partition or holocaust?

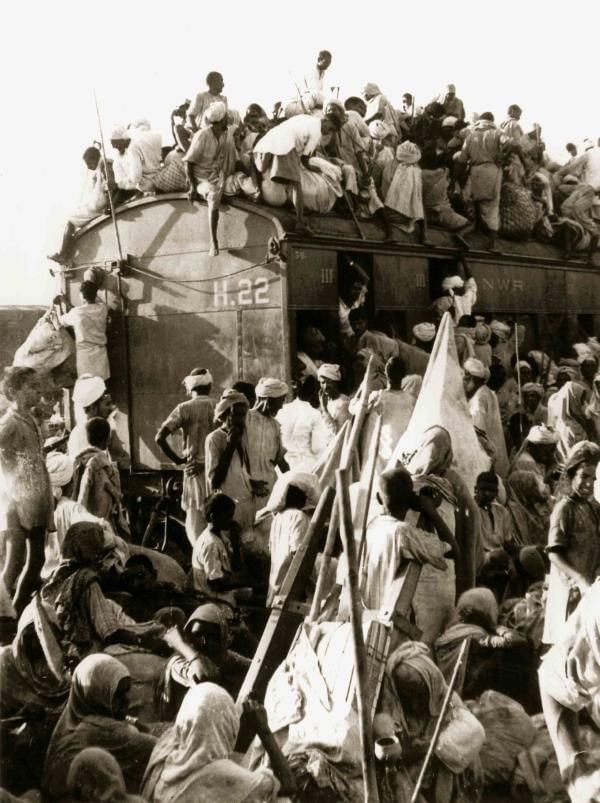

- The narratives just presented point to the pervasive violence that characterised Partition. Several hundred thousand people were killed and innumerable women raped and abducted. Millions were uprooted, transformed into refugees in alien lands.

- It is impossible to arrive at any accurate estimate of casualties: informed and scholarly guesses vary from 200,000 to 500,000 people. In all probability, some 15 million had to move across hastily constructed frontiers separating India and Pakistan. As they stumbled across these “shadow lines” – the boundaries between the two new states were not officially known until two days after formal independence – they were rendered homeless, having suddenly lost all their immovable property and most of their movable assets, separated from many of their relatives and friends as well, torn asunder from their moorings, from their houses, fields and fortunes, from their childhood memories. Thus stripped of their local or regional cultures, they were forced to begin picking up their life from scratch.

- Was this simply a partition, a more or less orderly constitutional arrangement, an agreed-upon division of territories and assets? Or should it be called a sixteen-month civil war, recognising that there were well-organised forces on both sides and concerted attempts to wipe out entire populations as enemies? The survivors themselves have often spoken of 1947 through other words: “maashal-la” (martial law), “mara-mari’ (killings), and “raula”, or “hullar” (disturbance, tumult, uproar). Speaking of the killings, rape, arson, and loot that constituted Partition, contemporary observers and scholars have sometimes used the expression “holocaust” as well, primarily meaning destruction or slaughter on a mass scale. Is this usage appropriate? You would have read about the German Holocaust under the Nazis in Class IX.

- The term “holocaust” in a sense captures the gravity of what happened in the subcontinent in 1947, something that the mild term “partition” hides. It also helps to focus on why Partition, like the Holocaust in Germany, is remembered and referred to in our contemporary concerns so much.

- Yet, differences between the two events should not be overlooked. In 1947-48, the subcontinent did not witness any state-driven extermination as was the case with Nazi Germany where various modern techniques of control and organisation had been used. The “ethnic cleansing” that characterised the partition of India was carried out by self-styled representatives of religious communities rather than by state agencies.

Partition: A Deep-Rooted Legacy

The memories, hatreds, and stereotypes formed during the Partition continue to shape the identities and history of people on both sides of the India-Pakistan border.

- Ongoing Impact: The Partition created a legacy of memories, hatreds, stereotypes, and identities that still influence the history of people in India and Pakistan.

- Cycle of Conflict: Hatreds from the Partition have led to inter-community conflicts, and these communal clashes, in turn, keep the memories of past violence alive.

- Deepening Divides: Stories of Partition violence are used by communal groups to deepen the divide between communities. They instill feelings of suspicion and distrust, reinforce communal stereotypes, and promote the problematic idea that Hindus, Sikhs, and Muslims are distinct communities with conflicting interests.

- Shaping Identities: The identities of people on both sides of the border are shaped by the memories and narratives of the Partition. This has created a cycle where past violence influences present perceptions, and present conflicts are rooted in past grievances.

- India-Pakistan Relations: The relationship between India and Pakistan has been profoundly influenced by the legacy of the Partition. The conflicting memories of this period shape how communities perceive each other on both sides of the border.

- Partition's Aftermath: The aftermath of the Partition was not just a historical event but a significant moment that continues to influence the socio-political landscape of both countries. The way communities remember and narrate the Partition plays a crucial role in contemporary politics and inter-community relations.

Why and How Did Partition Happen?

Some historians argue that the idea of Hindus and Muslims in India being two separate nations, proposed by Mohammad Ali Jinnah, can be traced back to medieval history. They believe that the events of 1947 were closely linked to a long history of conflict between Hindus and Muslims during medieval and modern times. However, this perspective overlooks the fact that the history of conflict has existed alongside a history of sharing and cultural exchange between the communities. It also fails to consider the changing circumstances that influence people's beliefs.

Other scholars view Partition as the result of communal politics that began to develop in the early twentieth century. They argue that the colonial government's introduction and expansion of separate electorates for Muslims in 1909 and 1919 significantly influenced communal politics. Separate electorates allowed Muslims to elect their own representatives in designated constituencies, leading politicians to use sectarian slogans and appeal to their own religious groups. This deepened and hardened community identities, turning them into symbols of opposition and hostility between communities.

However, while separate electorates had a strong impact on Indian politics, it is important not to overstate their significance or view Partition as an inevitable outcome of their implementation. Communal identities were also strengthened by various other developments in the early twentieth century. During the 1920s and early 1930s, tensions escalated around issues such as the

- "music-before-mosque" controversy, the cow protection movement, and the Arya Samaj's efforts to reconvert Muslims who had recently converted to Islam.

- Hindus were also provoked by these issues, contributing to the growing communal tension.

The spread of tabligh (propaganda) and tanzim (organization) after 1923 angered many. Middle-class publicists and communal activists aimed to strengthen solidarity within their communities, rallying people against the other community. This led to a surge of riots in various parts of the country. Each riot further deepened the rift between communities, leaving behind painful memories of violence. However, it would be a mistake to view Partition as simply the result of escalating communal tensions. As the main character in the film "Garm Hawa," which depicts Partition, states, "Communal discord existed even before 1947, but it never resulted in the displacement of millions from their homes." Partition was a fundamentally different event from previous communal politics. To grasp its nature, we need to closely examine the events of the final decade of British rule.

What is Communalism?

- Communalism refers to a political ideology that aims to unify a community based on a religious identity, particularly in opposition to another community. It seeks to establish this identity as fundamental and fixed, often downplaying internal distinctions within the community. Communalism emphasizes the essential unity of the community against others, fostering an environment of hostility and conflict.

- For instance, in the context of India, communalism may manifest as Hindu communalism or Muslim communalism, where the focus is on promoting the interests of one religious group at the expense of another. This ideology often leads to a politics of hatred and violence, as it seeks to define and solidify community boundaries in a way that exacerbates divisions.

Communalism in Politics:

- Communalism is a specific type of politics centered on religious identity, aiming to consolidate one community around a religious identity in opposition to another community. It seeks to establish this community identity as fundamental and fixed, often suppressing distinctions within the community. The emphasis is on the essential unity of the community against others.

- Examples: In the context of India, Hindu communalism and Muslim communalism are common forms, where the focus is on promoting the interests of one religious group at the expense of another. This leads to a politics of hatred and violence, defining and solidifying community boundaries in a way that exacerbates divisions.

Distinction from Sectarianism:

- Sectarianism is often confused with communalism, but it is different. Sectarianism refers to conflict between different sects within the same religion, while communalism focuses on conflict between different religions.

Examples of Communalism:

- Hindu Communalism: This form of communalism seeks to promote the interests of Hindus at the expense of other religious communities, often portraying Muslims and Christians as threats to Hindu culture and identity. It aims to unify Hindus around a common religious identity and often involves the vilification of other communities.

- Muslim Communalism: Similar to Hindu communalism, this ideology seeks to promote the interests of Muslims, often in opposition to Hindus. It aims to unify Muslims around a common religious identity and can involve the portrayal of Hindus as adversaries.

- Sikh Communalism: This form of communalism focuses on promoting Sikh interests, often in opposition to Hindus and Muslims. It seeks to unify Sikhs around a common religious identity and can involve the vilification of other communities.

- Christian Communalism: This ideology seeks to promote the interests of Christians, often in opposition to Hindus and Muslims. It aims to unify Christians around a common religious identity and can involve the portrayal of other communities as threats.

Impact of Communalism:

- Communalism nurtures a politics of hatred for an identified "other," leading to violence and conflict. It seeks to suppress distinctions within the community and promote a singular, fixed identity, often based on religion.

- Communalism is a politics that seeks to define and solidify community identity around a religious core, often in opposition to other communities. It emphasizes the essential unity of the community against others and is marked by a politics of hatred for an identified "other."

- Communalism is a specific type of politics that focuses on unifying a community around a religious identity in opposition to another community. It aims to establish this identity as fundamental and fixed, often suppressing distinctions within the community. The emphasis is on the essential unity of the community against others.

The Provincial Elections of 1937 and the Congress Ministries

In 1937, provincial legislature elections were conducted for the first time in India, but the right to vote was limited to only about 10 to 12 per cent of the population. The Indian National Congress (INC) performed well in these elections, securing an absolute majority in five out of eleven provinces and forming governments in seven provinces. However, the Congress struggled in constituencies reserved for Muslims.

- The Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, also did poorly in the elections, capturing only 4.4 per cent of the total Muslim vote. The League failed to win any seats in the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and managed to secure only two out of 84 reserved constituencies in Punjab and three out of 33 in Sind. Despite its limited success, the League attempted to position itself as the representative of Muslim interests.

- In the United Provinces, where the Congress had an absolute majority, the Muslim League proposed a coalition government. The Congress rejected this offer, which some scholars believe convinced the League that a united India would diminish Muslim political power. The League began to see itself as the sole representative of Muslim interests, while the Congress was viewed as primarily a Hindu party.

- Initially founded in 1906, the Muslim League had been dominated by the Muslim elite from the United Provinces. Over time, it began to demand autonomy for Muslim-majority areas, laying the groundwork for future demands for Pakistan in the 1940s. The Congress ministries, particularly in the United Provinces, deepened the rift between the two parties. The Congress rejected the League's proposal for a coalition government partly because the League supported landlordism, while the Congress aimed to abolish it, although it had not yet taken significant steps in that direction.

- The Congress's efforts at "Muslim mass contact" did not yield substantial results. Instead, its secular and radical rhetoric alienated conservative Muslims and the Muslim landed elite without gaining the support of the Muslim masses. This period marked the beginning of the Muslim League's intensified efforts to expand its social support, particularly in regions that would later become part of Pakistan, such as Bengal, the NWFP, and Punjab.

The Muslim League

In the late 1930s, while the top leaders of the Congress Party were strongly advocating for secularism, this belief was not shared by everyone within the party or even by all Congress ministers.

- Maulana Azad, a key Congress leader, highlighted in 1937 that while Congress members were prohibited from joining the Muslim League, they were active in the Hindu Mahasabha, particularly in the Central Provinces (now Madhya Pradesh). It wasn't until December 1938 that the Congress Working Committee officially barred its members from being part of the Mahasabha.

- This period also saw the rise of the Hindu Mahasabha and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The RSS, originating from Nagpur, expanded its influence to the United Provinces, Punjab, and other regions during the 1930s. By 1940, the RSS had over 100,000 trained cadres committed to Hindu nationalism, believing that India was fundamentally a Hindu land.

The “Pakistan” Resolution

The demand for Pakistan evolved over time. On March 23, 1940, the Muslim League passed a resolution calling for autonomy for Muslim-majority areas in the subcontinent.

- This resolution was vague and did not explicitly mention partition or the creation of Pakistan. Sikandar Hayat Khan, the Punjab Premier and a key figure in drafting the resolution, expressed his opposition to a Pakistan that would imply separate Muslim and Hindu rule. He advocated for a loose confederation with significant autonomy for its members.

- The roots of the Pakistan demand have been linked to the Urdu poet Mohammad Iqbal, who, in 1930, spoke of the need for a “North-West Indian Muslim state.” Iqbal's vision was not for a new country but for a reorganization of Muslim-majority areas into a confederation, which in contemporary terms refers to a union of largely autonomous states with a central government having limited powers.

The Name “Pakistan”

The term “Pakistan” was coined by a Punjabi Muslim student at Cambridge, Choudhry Rehmat Ali, in the 1930s. He advocated for a separate national status for this new entity, which he envisioned as comprising regions from Punjab, Afghanistan, Kashmir, Sindh, and Balochistan. Initially, Rehmat Ali's idea was not taken seriously, and many dismissed it as a student’s fantasy. However, it laid the groundwork for the eventual demand for Pakistan.

The Muslim League's Resolution of 1940

The Suddenness of Partition

- In 1940, the Muslim League was unclear about its demand for autonomy for Muslim-majority areas. There was only a brief period of seven years between the initial demand for autonomy and the actual Partition in 1947.

- At that time, no one fully understood what the creation of Pakistan would entail or how it would impact people's lives. Many individuals who migrated in 1947 believed they would eventually return to their original homes.

- Even within the Muslim leadership, the idea of Pakistan as a sovereign state was not taken seriously at first. Jinnah may have initially viewed the concept of Pakistan as a bargaining tool to prevent British concessions to the Congress and to secure better terms for Muslims.

- The Second World War put pressure on the British, delaying negotiations for Indian independence. However, it was the Quit India Movement starting in 1942, which persisted despite severe repression, that significantly weakened the British Raj and forced officials to engage in discussions with Indian parties about transferring power.

Post-War Developments

- When negotiations resumed in 1945, the British proposed the establishment of an entirely Indian central Executive Council as a step towards full independence, with only the Viceroy and the Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces remaining British.

- However, discussions stalled because Jinnah insisted that the League had the exclusive right to choose all Muslim members of the Executive Council and that decisions opposed by Muslims should require a two-thirds majority.

- This demand was remarkable given the political context, as many nationalist Muslims supported the Congress, which was represented by Maulana Azad in the discussions. In West Punjab, members of the Unionist Party were also aligned with the Congress.

- The League's insistence on these terms highlighted its strong position, even though it faced opposition from other Muslim factions.

The 1946 Elections and Their Aftermath

In 1946, provincial elections were held again in British India. The Indian National Congress (INC) won a significant victory in the general constituencies, securing 91.3% of the non-Muslim vote. The All-India Muslim League (AIML) also had a remarkable success, winning all 30 reserved Muslim constituencies in the Centre with 86.6% of the Muslim vote and 442 out of 509 seats in the provinces.

- Despite the INC's success, the AIML established itself as the dominant party among Muslim voters, claiming to be the "sole spokesman" for India's Muslims. However, it is important to note that the franchise was very limited at the time, with only 10 to 12% of the population having the right to vote in provincial elections and just one percent in the elections for the Central Assembly.

- Following the elections, the British Cabinet sent a three-member mission to India in March 1946 to address the League's demand for a separate state and to propose a political framework for a free India. The Cabinet Mission recommended a loose three-tier confederation with a weak central government controlling foreign affairs, defense, and communications. The existing provincial assemblies would be grouped into three sections, with the power to establish their own intermediate-level executives and legislatures.

- Initially, major political parties accepted the Cabinet Mission's plan. However, the agreement was short-lived due to differing interpretations. The AIML wanted the grouping to be compulsory, while the INC preferred that provinces have the option to join a group. This disagreement led to the rejection of the Cabinet Mission's proposal and made partition appear inevitable. Most Congress leaders eventually accepted partition as a tragic but unavoidable outcome, while only Mahatma Gandhi and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan of the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) continued to oppose the idea of partition.

Arguments by Mahatma Gandhi Against the Idea of Pakistan

Mahatma Gandhi strongly opposed the idea of Pakistan, believing that it would lead to a tragic division between Hindus and Muslims. He envisioned a future where both communities would live together harmoniously, without the need for separation.

Key Points from Gandhi's Argument:

- Unity of Hindus and Muslims: Gandhi emphasized that Hindus and Muslims share the same soil, blood, food, water, and language. He believed that these commonalities should foster unity rather than division.

- Critique of Partition: He viewed the demand for Pakistan as un-Islamic and sinful, arguing that Islam promotes the unity and brotherhood of all humanity, not the disruption of its oneness.

- Warning Against Division: Gandhi warned that those who seek to divide India into warring factions would be enemies of both Islam and India. He believed that such divisive actions would ultimately harm both communities.

- Personal Conviction: He expressed his personal conviction that the idea of Pakistan was wrong and that he would not subscribe to any notion that he deemed incorrect.

Gandhi's arguments reflect his deep commitment to communal harmony and his vision of a united India, where Hindus and Muslims could coexist peacefully without the specter of partition.

Towards Partition

After withdrawing support for the Cabinet Mission plan, the Muslim League opted for "Direct Action" to pursue its demand for Pakistan. It declared August 16, 1946 as "Direct Action Day." On this day, violent riots erupted in Calcutta, lasting for several days and resulting in thousands of deaths. By March 1947, this violence had spread to various parts of northern India.

In March 1947, the Congress leadership proposed dividing the Punjab into two regions: one with a Muslim majority and the other with a Hindu/Sikh majority. They also suggested applying the same principle to Bengal. At this point, many Sikh leaders and Congress members in the Punjab believed that Partition was a necessary measure to avoid being overwhelmed by Muslim majorities and Muslim leaders. Similarly, in Bengal, some bhadralok Bengali Hindus, concerned about losing political power to Muslims, felt that dividing the province was the only way to maintain their political influence, as they were in a numerical minority.

Withdrawal of Law and Order

- The violence persisted for nearly a year, starting from March 1947. A key factor contributing to this was the disintegration of governance structures.

- Penderel Moon, an administrator in Bahawalpur (now in Pakistan), observed the police's failure to intervene during incidents of arson and murder in Amritsar in March 1947.

- Later in the year, Amritsar district witnessed severe bloodshed due to a complete breakdown of authority.

- British officials were at a loss on how to manage the escalating situation. They were reluctant to make decisions and hesitant to intervene.

- When frantic citizens sought assistance, British officials suggested contacting Indian leaders like Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru, Vallabh Bhai Patel, or M.A. Jinnah.

- There was confusion about who held authority and power at the time.

- Most Indian leaders, except for Mahatma Gandhi, were preoccupied with independence negotiations, while many Indian civil servants in the troubled provinces were concerned for their own safety.

- The British were focused on preparing to leave India.

- The situation worsened as Indian soldiers and policemen began to identify with specific religious communities— Hindus, Muslims, or Sikhs.

- As communal tensions escalated, the professionalism of those in uniform could not be depended upon.

- In several instances, policemen not only assisted their co-religionists but also attacked members of other communities.

The One-Man Army

Amidst the chaos and violence during the Partition, Mahatma Gandhi, at the age of 77, dedicated himself to restoring communal harmony. He believed in the power of non-violence and the possibility of changing people's hearts.

Gandhi traveled from the troubled villages of Noakhali in East Bengal (now Bangladesh) to the conflict-ridden areas of Bihar, Calcutta, and Delhi, striving to prevent Hindus and Muslims from killing each other. He focused on reassuring the minority communities and fostering mutual trust between Hindus and Muslims.

Efforts in East Bengal

- In October 1946, when Muslims in East Bengal targeted Hindus, Gandhi visited the region, walking through villages and persuading local Muslims to ensure the safety of Hindus.

Building Trust in Delhi

- In Delhi, Gandhi worked to create a spirit of mutual confidence between the two communities. His arrival in the city was seen by many Muslims as a beacon of hope, likened to the arrival of much-needed rain after a long drought.

Addressing Sikh Concerns

- On 28 November 1947, during a speech at Gurdwara Sisganj on Guru Nanak's birthday, Gandhi highlighted the absence of Muslims in Chandni Chowk, emphasizing the shame of driving Muslims out of the city.

Fasting for Peace

- Gandhi continued his efforts in Delhi, opposing the mentality of those wanting to expel Muslims, whom they viewed as Pakistanis. When he began a fast to promote peace, Hindu and Sikh migrants joined him, creating a powerful impact.

Gandhi's Martyrdom

- Despite the positive changes, it was Gandhi's assassination that ultimately halted the cycle of violence against Muslims in Delhi. His sacrifice made people realize the futility of the violence they had inflicted.

Impact of Gandhi's Efforts

- Many Muslims in Delhi later reflected on this period, noting how Gandhi's presence and actions transformed the situation, saving the city from further bloodshed.

Women were forcibly “recovered” by the Indian and Pakistani governments after the partition, despite their new circumstances and relationships. The authorities believed these women were on the wrong side of the border and did not consult them, undermining their right to make decisions about their own lives. An estimated 30,000 women were “recovered” in total, with 22,000 Muslim women sent back to India and 8,000 Hindu and Sikh women sent back to Pakistan, in an operation that continued until 1954.

Preserving “honour”

During the period of intense physical and psychological danger, the idea of preserving community honour played a significant role. This concept of honour was rooted in a traditional view of masculinity in North Indian peasant societies, where honour was tied to the ownership of zan (women) and zamin (land). Virility was associated with the ability to protect these possessions from being taken by outsiders. Conflicts often arose over these two primary "possessions."

- Women also internalized these values. In some cases, when men feared that their women—wives, daughters, sisters—would be violated by the "enemy," they resorted to killing the women themselves. Urvashi Butalia, in her book The Other Side of Silence, recounts a horrific incident in the village of Thoa Khalsa, Rawalpindi district, during the Partition.

- In this Sikh village, ninety women reportedly chose to jump into a well rather than fall into "enemy" hands. The migrant refugees from this village commemorate this event at a gurdwara in Delhi, viewing the deaths as martyrdom rather than suicide. They believe that men at the time had to courageously accept the women's decision and, in some cases, persuade them to take their own lives.

- Every year on March 13, the community celebrates this "martyrdom," recounting the incident to an audience of men, women, and children. Women are encouraged to remember the sacrifice and bravery of their sisters and to emulate their example. For the survivors' community, this remembrance ritual helps keep the memory alive. However, these rituals do not acknowledge the stories of those who did not wish to die and had to end their lives against their will.

Regional Variations

The experiences of ordinary people during the Partition varied significantly across different regions of the subcontinent. While we have primarily focused on the north-western part, it's important to understand what happened in places like Bengal, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Central India, and the Deccan.

- Bengal: In Bengal, the migration process was prolonged and painful, with people moving across a porous border over an extended period. Unlike Punjab, the population exchange in Bengal was not nearly total. Many Bengali Hindus remained in East Pakistan, while a significant number of Bengali Muslims continued to live in West Bengal. The division of Bengal led to suffering that, while less concentrated, was equally agonizing. Bengali Muslims (East Pakistanis) later rejected Jinnah’s two-nation theory through political action, leading to the creation of Bangladesh in 1971-72. The shared religion of Islam could not hold East and West Pakistan together.

- Punjab: The Punjab experienced the most bloody and destructive violence during the Partition. There was near-total displacement of Hindus and Sikhs from West Punjab into India and almost all Punjabi-speaking Muslims moving to Pakistan. This massive population transfer happened relatively quickly, between 1946 and 1948. In both Punjab and Bengal, women and girls became prime targets of persecution. Their bodies were treated as territory to be conquered, and dishonoring women from a community was seen as a way to dishonor the entire community, serving as a means of revenge.

- Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh: Muslim families from these regions continued to migrate to Pakistan through the 1950s and early 1960s, although many chose to remain in India. Those who migrated, known as muhajirs in Pakistan, primarily settled in the Karachi-Hyderabad region in Sind.

- Central India and the Deccan: While specific details about these regions during the Partition are less documented, it is clear that the impact was felt across the subcontinent, with variations in the intensity and nature of the violence and displacement.

Partition, Poetry, Films and Literature

Partition literature and films are more effective in portraying the events of Partition than the works of historians. This is because they focus on individual suffering and pain, showing the impact on ordinary people whose lives were changed by this big event.

- Partition literature and films aim to make us understand the deep suffering and pain caused by this event. They do this by telling the stories of individuals or small groups of people, helping us see the impact on their lives and how the event shaped their destinies.

- Partition literature and films are available in many languages, including Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Bengali, Assamese, and English.

Famous Writers and Filmmakers on Partition

Some well-known writers and filmmakers who have explored the theme of Partition include:

Writers:

- Saadat Hasan Manto - A prominent Urdu writer known for his poignant short stories about Partition.

- Rajinder Singh Bedi - An Urdu writer whose works reflect the trauma of Partition.

- Intizar Hussain - An Urdu writer whose stories often touch upon themes of loss and displacement.

- Bhisham Sahni - A Hindi writer known for his novel "Tamas," which deals with the horrors of Partition.

- Kamaleshwar - A Hindi writer whose works explore the impact of Partition.

- Narain Bharati - A Bengali writer whose stories reflect on the aftermath of Partition.

Filmmakers:

- Ritwik Ghatak - A Bengali filmmaker known for films like "Meghe Dhaka Tara" and "Subarnarekha," which depict the struggles of refugees after Partition.

- M. S. Sathyu - Known for his film "Garam Hava," which addresses the issues faced by Muslims after Partition.

- Govind Nihalani - A filmmaker whose works often explore social and political themes, including Partition.

Poems and Writings on Partition

In addition to stories and films, there are also memorable poems and writings about Partition in Punjabi, Urdu, and Bengali. Some writers have shared their memories of Partition in poetry, capturing the emotions and experiences of that time.

Films on Partition

There are various films that depict the events of Partition, directed by notable filmmakers. Some of these films include:

- "He Who Has Not Seen Lahore" (Jis ne Lahore Nahin Dekha) - Directed by Habib Tanvir, this play explores the theme of Partition through the lens of those who experienced it.

- "Garam Hava" (Hot Winds) - Directed by M. S. Sathyu, this film portrays the struggles of a Muslim family in the aftermath of Partition.

- "Meghe Dhaka Tara" (The Cloud-Capped Star) - Directed by Ritwik Ghatak, this film depicts the life of a refugee family in post-Partition Bengal.

- "Subarnarekha" - Also directed by Ritwik Ghatak, this film continues the story of refugees and their struggles in post-Partition India.

- "Garam Hava" (Hot Winds) - Directed by M. S. Sathyu, this film portrays the struggles of a Muslim family in the aftermath of Partition.

Help, Humanity, Harmony

Buried under the debris of the violence and pain of Partition is an enormous history of help, humanity and harmony. Many narratives such as Abdul Latif’s poignant testimony, with which we began, reveal this. Historians have discovered numerous stories of how people helped each other during the Partition period, stories of caring and sharing, of the opening of new opportunities, and of triumph over trauma. Consider, for instance, the work of Khushdeva Singh, a Sikh doctor specializing in tuberculosis treatment in Dharampur, Himachal Pradesh.

Khushdeva Singh's Efforts: Immersing himself in his work day and night, he provided healing, food, shelter, love, and security to numerous migrants, regardless of their religion.

Building Trust: The residents of Dharampur developed immense faith in his humanity and generosity, comparable to the trust that Delhi Muslims and others had in Gandhiji.

A Plea for Help: Muhammad Umar, a migrant, wrote to Khushdeva Singh, expressing his need for safety and protection under Singh's care.

Memoir of Relief Work: Singh documented his relief efforts in a memoir titled "Love is Stronger than Hate: A Remembrance of 1947," describing his work as a duty to fellow human beings.

Visits to Karachi: Singh fondly recalled two visits to Karachi in 1949, highlighting the connections he maintained with old friends and acquaintances.

Oral Histories and History

Have you observed the various materials that form the basis of the history of Partition in this chapter? Oral narratives, memoirs, diaries, family histories, and first-hand written accounts all contribute to our understanding of the struggles and hardships faced by ordinary people during the Partition of the country. For millions, Partition was not just a constitutional division or a result of party politics involving the Muslim League, Congress, and others. It represented a profound upheaval in their lives between 1946 and 1950 and beyond, necessitating psychological, emotional, and social adjustments. Similar to the Holocaust in Germany, we should perceive Partition not merely as a political event but through the lens of its significance to those who experienced it. Memories and experiences shape the reality of an event.

- One of the advantages of personal reminiscence, a type of oral source, is its ability to capture experiences and memories in intricate detail. It allows historians to craft richly detailed and vivid accounts of what transpired during events like Partition, something that government documents cannot provide. Government records primarily focus on policy matters, party affairs, and state-sponsored initiatives. In the context of Partition, while government reports and the personal writings of high-level officials offer insights into negotiations between the British and major political parties regarding India’s future or refugee rehabilitation, they shed little light on the daily experiences of those impacted by the decision to divide the country.

- Oral history also enables historians to expand the scope of their discipline by resurrecting the experiences of the poor and powerless, such as Abdul Latif’s father, the women of Thoa Khalsa, a refugee selling gunny bags for a meager living, a middle-class Bengali widow working on road construction in Bihar, and a Peshawari trader who, upon migrating to India, was pleased to secure a minor job in Cuttack, despite his ignorance of the city. By focusing on individuals whose lives have been overlooked or taken for granted in mainstream history, the oral history of Partition provides a significant perspective often disregarded in traditional narratives.

- However, some historians remain doubtful of oral history, arguing that oral data lack concreteness and precision, making generalizations difficult. They believe that personal experiences are unique and may not contribute to a broader understanding of historical processes. Nevertheless, in the context of events like the Partition and the Holocaust, there is abundant testimony regarding the various forms of distress experienced by numerous individuals. Historians can weigh the reliability of evidence by comparing statements, corroborating findings with other sources, and being cautious of internal contradictions.

- Oral history is not concerned with trivial matters; rather, it focuses on experiences central to the narrative. Different types of sources are necessary for addressing different questions. For instance, government reports may provide information on the number of “recovered” women exchanged by the Indian and Pakistani states, but it is the women themselves who can recount their suffering.

Introduction

Partition refers to the division of British India into two independent dominions, India and Pakistan, which took place on August 15, 1947. This event was marked by the mass migration of populations across the newly drawn borders, communal violence, and significant upheaval. The term "Partition" is often used to describe not just the political and territorial division, but also the social and human consequences that followed.

The demand for Pakistan did not emerge suddenly. Throughout the 1930s, several factors contributed to the growing call for a separate Muslim state:

- Iqbal's Vision (1930): The Urdu poet Mohammad Iqbal envisioned a “North-West Indian Muslim state” as an autonomous unit within a loose Indian federation. His idea highlighted the distinct identity and needs of Muslims in North-West India.

- Coining of "Pakistan" (1933): Choudhry Rehmat Ali, a Punjabi Muslim student at Cambridge, coined the term "Pakistan," advocating for a separate nation for Muslims in North-West India. This term encapsulated the growing aspiration for a distinct Muslim identity and governance.

- Political Realities (1937-39): The period saw Congress ministries coming to power in seven out of 11 provinces of British India. However, the Muslim League felt that Muslim interests were not adequately represented, which fueled the demand for a separate state where Muslims could have autonomy and safeguard their rights.

- Lahore Resolution (1940): The Muslim League officially demanded a measure of autonomy for Muslim-majority areas, marking a significant step towards the call for Pakistan. This resolution reflected the urgent need for political recognition and self-governance for Muslims in British India.

The events leading to Partition were complex and rooted in the evolving political landscape of British India, where the aspirations and identities of different communities were increasingly coming to the forefront.

Partition was a gradual process influenced by various political, social, and cultural factors. Here’s an elaboration on why some viewed it as sudden:

- Political Developments: The political landscape of British India in the 1940s was marked by increasing tensions between the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League. The Congress, which represented a broad coalition including many Hindus, was pushing for a unified India, while the Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah, was advocating for the rights of Muslims, who they believed would be a minority in a united India. This growing rift was evident in the 1946 provincial elections, where the Congress won a majority in the general constituencies, but the League’s success in Muslim seats was also significant.

- British Response: The British government’s inability to find a workable solution to the demands of both parties added to the urgency. The Cabinet Mission of 1946 attempted to negotiate a solution but failed, leading to increased tensions. In August 1946, the Muslim League called for "Direct Action" to press for its demands, which escalated tensions further.

- Communal Violence: The violence that erupted, especially in places like Calcutta, highlighted the deepening divisions and made the idea of a united India seem increasingly unfeasible. The communal riots were a stark indication of the animosities that had developed, contributing to the perception that Partition was becoming inevitable.

- Rapid Decision-Making: The decision for Partition came rapidly in mid-1947, with the Labour government in Britain deciding to leave India. The Mountbatten Plan, announced in June 1947, proposed the division of India into two separate states, which was accepted by the major political leaders. This swift decision, in the context of the escalating violence, contributed to the perception of Partition as a sudden development.

Ultimately, while the groundwork for Partition was laid over several years, the events of the mid-1940s, marked by political strife and communal tensions, created a situation where Partition appeared to be the only viable solution.

Ordinary people experienced Partition as a traumatic and chaotic upheaval in their daily lives. Here’s how their perspective differed from the political narrative:

- Sudden Disruption: For many, the announcement of Partition and the subsequent communal violence came as a shock. Families found themselves uprooted, often with little warning, as people rushed to cross borders to avoid violence or to reach relatives in the newly formed states.

- Personal Loss and Trauma: Ordinary individuals faced immense personal loss, including the death of family members, loss of homes, and the destruction of their communities. The violence that accompanied the migration led to atrocities that left deep psychological scars.

- Communal Bonds: Many people who had lived peacefully with their neighbors found themselves in conflict due to the sudden imposition of communal identities. Neighbors who were once friends became enemies, and long-standing relationships were severed.

- Migration Experience: The journey to the new borders was fraught with danger. People faced harassment, violence, and harassment, making what should have been a straightforward migration into a harrowing experience.

- New Beginnings: Upon reaching the new territories, many individuals had to start from scratch, facing challenges in finding housing, jobs, and rebuilding their lives in unfamiliar environments. The new borders did not guarantee safety or stability, and many faced continued difficulties.

- Long-term Impact: The impact of Partition was felt for decades, with many individuals carrying the memories of their experiences throughout their lives. The trauma and disruption influenced personal and communal identities, leading to long-lasting repercussions in the socio-political fabric of the region.

For ordinary people, Partition was not just a political event but a profound personal crisis that altered their lives irrevocably. Their experiences were marked by a mix of fear, loss, and the struggle to adapt to a rapidly changing reality.

Mahatma Gandhi opposed Partition for several reasons:

- Unity of India: Gandhi believed in a united India where all communities, including Hindus and Muslims, could live together harmoniously. He felt that Partition would lead to further divisions and communal strife.

- Communal Harmony: Gandhi had always advocated for communal harmony and mutual respect among different religious groups. He feared that Partition would exacerbate communal tensions and violence, leading to a breakdown of social fabric.

- Non-violence: Gandhi's principle of non-violence (ahimsa) was central to his philosophy. He believed that the struggle for independence should be based on non-violent principles, and Partition, with its accompanying violence and bloodshed, contradicted this ethos.

- Historical Precedent: Gandhi viewed India as a land with a long history of diverse communities living together. He cited examples from Indian history where different communities coexisted peacefully, arguing that such coexistence was possible in the future as well.

- Legacy: Gandhi wanted to leave behind a legacy of unity and peace. He believed that agreeing to Partition would tarnish the struggle for independence and create a legacy of division and conflict.

1946 - 1947: Prelude to Partition

- August 16, 1946: The Great Calcutta Killings mark the beginning of widespread communal violence, resulting in thousands of deaths.

- March 1947: The Congress high command proposes the division of Punjab and Bengal based on religious majorities, as the British prepare to leave India.

1947: The Actual Partition

- August 14-15, 1947: Pakistan is created, and India gains independence. Mahatma Gandhi travels to Noakhali in East Bengal to promote communal harmony amidst the chaos.

Introduction to Partition's Significance

- The Partition of British India in 1947 is considered a pivotal moment in South Asian history due to its profound and lasting impacts.

- This event not only reshaped the political landscape of the region but also had far-reaching consequences on social, cultural, and economic aspects.

Immediate Aftermath and Violence

- The partition led to one of the largest mass migrations in history, with an estimated 10-15 million people crossing borders to join their respective religious-majority nations.

- This migration was accompanied by horrific communal violence, with estimates of up to 2 million deaths and widespread atrocities.

Long-term Impact on India and Pakistan

- The newly formed nations faced immense challenges, including the integration of refugees, communal tensions, and the task of building governance structures.

- The partition also sowed the seeds for future conflicts, most notably over the Kashmir region, which remains a contentious issue to this day.

Social and Cultural Ramifications

- The division not only redefined borders but also had a lasting impact on identities, with religion becoming a central aspect of national identity in both India and Pakistan.

- Cultural exchanges and relationships were disrupted, leading to a reconfiguration of cultural identities that continue to evolve.

Economic Consequences

- The partition disrupted economic ties and trade routes, with industries and agricultural lands being split between the two countries.

- Over time, both nations had to forge their own economic paths, with varying degrees of success and challenges.

Political Legacy

- The political landscape of South Asia was irrevocably altered, with both India and Pakistan establishing their identities as secular and Islamic republics, respectively.

- The legacy of partition continues to influence politics, with issues of communalism, nationalism, and regional autonomy remaining at the forefront.

Conclusion

- The Partition of 1947 is a significant marker in South Asian history because it not only transformed the geographical and political landscape but also had deep and lasting effects on society, culture, and international relations in the region.

- Understanding this event is crucial to grasping the complexities of contemporary South Asia.

|

210 videos|855 docs|219 tests

|

FAQs on NCERT Summary: Theme-14 Politics, Memories, Experiences (Class 12) - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What were the main reasons behind the Partition of India in 1947? |  |

| 2. How did the Muslim League contribute to the Partition of India? |  |

| 3. What was the impact of regional variations on the Partition experience? |  |

| 4. How did literature and films depict the Partition experience? |  |

| 5. What role did the concepts of help, humanity, and harmony play during the Partition? |  |