Power and Piety: The Maurya Empire, c. 324–187 BCE - 1 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

The Major Sources for the Maurya Period

Kautilya's Arthashastra

- Kautilya's Arthashastra is a highly intricate and comprehensive manual on governance and statecraft. In this text, the concept of artha is central. Artha, as one of the four purusharthas or legitimate aims of human life, refers to material prosperity. Kautilya argues that artha is more important than dharma (spiritual welfare) and kama (pleasure) because the latter two depend on artha.

- He defines artha as the means of sustenance and livelihood, which comes from the earth and its people. Thus, the Arthashastra is essentially about how to acquire and protect these resources, making it a science of statecraft. The text is divided into 15 books, covering topics like internal administration and foreign relations.

- Kautilya and the Arthashastra:Authorship and Date: The Arthashastra is traditionally believed to have been written by Kautilya in the 4th century BCE. Kautilya, also known as Chanakya, was a key figure in helping Chandragupta Maurya overthrow the Nanda dynasty.

- Internal Evidence: Two verses within the Arthashastra support the traditional view of its authorship and date. Verse 1.1.19 credits Kautilya with composing the work, while verse 15.1.73 speaks of Kautilya’s role in regenerating the shastra and the earth under Nanda control.

- Later Works: Subsequent texts like Kamandaka’s Nitisara and Dandin’s Dashakumaracharita align with the traditional dating and authorship of the Arthashastra.

- Challenges to Traditional View: Some scholars argue that the verses supporting Kautilya’s authorship are later additions and that his name in the text could refer to his teachings rather than his authorship.

- Historical References: The absence of Kautilya’s mention in Patanjali’s Mahabhashya and Megasthenes’ Indica has been used to question the traditional dating. However, these works have different focuses and their references to historical figures are not always comprehensive.

What does the text say about the Arthashastra?

- The Arthashastra is believed to be a work of a scholar rather than someone directly involved in politics.

- Despite its focus on inter-state relations that may seem applicable to a smaller state, the Arthashastra reflects imperial ambitions and the perspective of a would-be conqueror aiming to dominate the entire subcontinent.

- The text outlines a detailed administrative structure and suggests high salaries for officials, indicating the author had a large, established polity in mind.

Differences between Arthashastra and Megasthenes’ Indica

- A comparison between the Arthashastra and Megasthenes’ Indica shows discrepancies in areas like fortifications, city and army administration, and taxation.

- Some argue these differences imply the works belong to different periods, with the Arthashastra being later than Megasthenes.

- However, this argument is flawed because Megasthenes was not always a reliable observer, and his work survives only in later paraphrases, making it an unreliable reference for dating the Arthashastra.

Lack of references to the Mauryas

- The Arthashastra does not mention the Mauryas, Chandragupta, or Pataliputra, which could be because it is a theoretical work on statecraft rather than a descriptive one.

- The objections to dating and authorship of the text can be countered by the idea that it discusses a potential state rather than an actual one.

Support for traditional dating

- Kangle argues for the traditional view placing Kautilya and the Arthashastra in the Maurya period based on various factors.

- The style of the book suggests it is earlier than Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra, possibly before the Yajnavalkya and Manu Smritis.

- References to the Ajivikas, sangha polities, and large-scale agricultural settlements align with the Maurya period.

- The administrative structure in the Arthashastra does not match any other historical dynasty.

Author's identity

- Kangle proposes that Vishnugupta is the personal name of the author, Kautilya his gotra name, and Chanakya a patronym.

- He suggests Kautilya wrote the Arthashastra after being insulted by the Nanda king and before joining Chandragupta Maurya.

Megasthenes' Indica

- During the Maurya period, trade with the Western world and the exchange of emissaries between Maurya and Hellenistic kings were expanding. Graeco-Roman accounts mention kings Chandragupta and Amitraghata, and their capital Pataliputra.

- Megasthenes, sent as an ambassador to the Maurya court after a treaty between Chandragupta and Seleucus, wrote a book called the Indica based on his experiences in India, which has not survived but is referenced in later works.

- Diodorus, a historian from Sicily, Strabo, a geographer from Pontus, Arrian, a statesman and historian from Bithynia, Pliny the Elder, a Roman scholar, and Claudius Aelianus, a Roman author on zoology, preserved Megasthenes' observations in their writings.

Megasthenes and Later References to His Work

- References to Megasthenes in texts by later writers often occur in contexts that are broader than just India. For example, Arrian, in his work Indica , makes it clear that his main focus is not on describing Indian customs but on recounting Alexander's journey from India to Persia, suggesting that his account of India is more of an aside.

- To writers like Arrian, 'India' referred to the land beyond the Indus River. It is unclear whether these writers had direct access to Megasthenes' work or were relying on secondary accounts of his writings.

- Not all of their statements were necessarily based on Megasthenes' Indica alone. Other writers such as Eratosthenes, Ktesius, Onesicritus, and Deimachus also contributed to their understanding of India, which might explain the differences in detail found in the accounts of Strabo, Diodorus, and Arrian.

Views of Later Graeco-Roman Writers on Megasthenes

- Later Graeco-Roman writers had different opinions about the accuracy and reliability of Megasthenes.

- Strabo and Pliny were very critical of Megasthenes.

- Arrian was more trusting of Megasthenes' accounts.

- Diodorus did not make negative comments about Megasthenes, but he omitted some of Megasthenes' strange and hard-to-believe stories about India and its people.

Strabo's Critique of Accounts on India

- Strabo emphasized the need to approach accounts of India with tolerance due to its great distance from Greece and the limited knowledge of those who reported on it. He noted that even those who had seen parts of India could only provide partial and hurried observations.

- Strabo pointed out the inconsistencies in reports from different individuals who had been on the same expeditions, highlighting the unreliability of hearsay information. He criticized earlier writers on India, placing Deimachus and Megasthenes at the top of the list of fabricators.

- Strabo accused them of inventing bizarre tales and reviving Homeric fables, such as those about giant ants and mythical creatures. He dismissed their accounts as falsehoods and questioned their credibility.

Arrian's Perspective on Megasthenes

- Arrian acknowledged that Megasthenes may not have traveled extensively in India, but he likely saw more of the country than those who accompanied Alexander the Great. Arrian noted that Megasthenes resided at the courts of Sandrocottus (Chandragupta Maurya), a prominent Indian king, and Porus, who was even greater.

- Arrian used this point to question the accounts of writers who described regions of India beyond the Hyphasis River (modern Beas River ). He suggested that the accounts of Alexander's expedition were more reliable for describing India up to the Hyphasis.

- Arrian referenced a specific account by Megasthenes about an Indian river called the Silas, which flowed through the land of the Silaeans. He described the river's unique property, where nothing could float or swim in its water, illustrating the strange and wondrous nature of Indian geography as reported by Megasthenes.

Early Greek Accounts of India

Megasthenes and Greek Writers

- Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador, wrote about India in his work Indica, describing its geography, people, and culture.

- Later Greek writers like Pliny also referenced Megasthenes but focused on different aspects of his accounts.

- These writers aimed to inform and entertain their Greek audience, highlighting similarities and differences between Greece and India.

Content of Indica

- Megasthenes described India’s size, rivers, soil, climate, plants, animals, and administration.

- He provided detailed accounts of Indian wildlife, including elephants and monkeys, and noted similarities in early human development between India and Greece.

Indian Legends and Worship

- Greeks noted Indian legends about early tribes and the gradual invention of arts.

- They observed similarities in worship, such as the Indian reverence for deities like Vasudeva Krishna, akin to their own gods Dionysus and Herakles.

Ideals and Errors in Greek Accounts

- Greeks idealized India, claiming it had no slavery, rare theft, and that farmers were untouched by war.

- However, they also made errors, such as Aelian’s claim about interest on loans and Strabo’s assertions about writing, metalworking, and wine consumption in India.

Megasthenes’ Observations on India:

- Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador, made observations about India that were later recorded by writers like Pliny and Diodorus.

- He compared the Ganga and Indus rivers to the Nile and Danube, noting differences in animal domestication between Greece and India.

- Fantastic Stories:

- Megasthenes mentioned bizarre tales such as one-horned horses with deer-like heads, enormous snakes, and the river Silas where nothing could float.

- He also described strange customs, including people living on a mountain called Nulo with backward-facing feet and eight toes on each foot, and another group with dog-like heads who communicated by barking.

- Gold-Digging Ants:

- Megasthenes reported the existence of gold-digging ants in the north-western mountains of India.

- Diodorus, another writer, omitted many of these fantastical accounts.

- Greek Interpretation of Megasthenes:

- The Greek references to Megasthenes’ Indica reflect how ancient Greeks viewed India through two filters: Megasthenes’ interpretation of his experiences and later Graeco-Roman writers’ interpretations of Megasthenes’ account.

- These citations reveal more about ancient Greek perspectives on India than about the actual history of the Indian subcontinent in the 4th century BCE.

Ashoka's Inscriptions

- Early Evidence of Brahmi Script: Short inscriptions on potsherds from the early 4th century BCE, discovered at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, provide significant evidence of the use of the Brahmi script before the Maurya period.

- Debates on Inscriptions: Historians debate the dating of inscriptions such as the Piprahwa casket, Sohgaura, and Mahasthan inscriptions, with some suggesting they are pre-Maurya or early Maurya, while others believe they are from Ashoka's time or later.

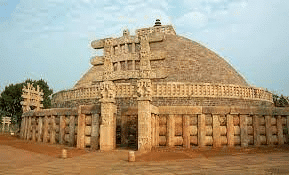

- Sanchi Inscription: A fragmentary inscription from Sanchi mentioning Bindusara may belong to the reign of the Maurya king of that name. However, the practice of inscribing imperial proclamations on stone is a notable feature of Ashoka's reign.

- James Prinsep and Ashoka's Edicts: When James Prinsep deciphered Ashoka's Brahmi edicts, he initially struggled to identify the king referred to in the inscriptions because Ashoka is mentioned by titles like Devanampiya (beloved of the gods) and Piyadasi (he who looks on auspiciousness). The Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa texts helped clarify this by confirming these titles referred to Ashoka.

- Discovery of Ashoka's Name: In later years, versions of Minor Rock Edict I that included Ashoka's personal name were found at sites like Maski, Udegolam, Nittur, and Gujjara, helping to identify the king in the inscriptions.

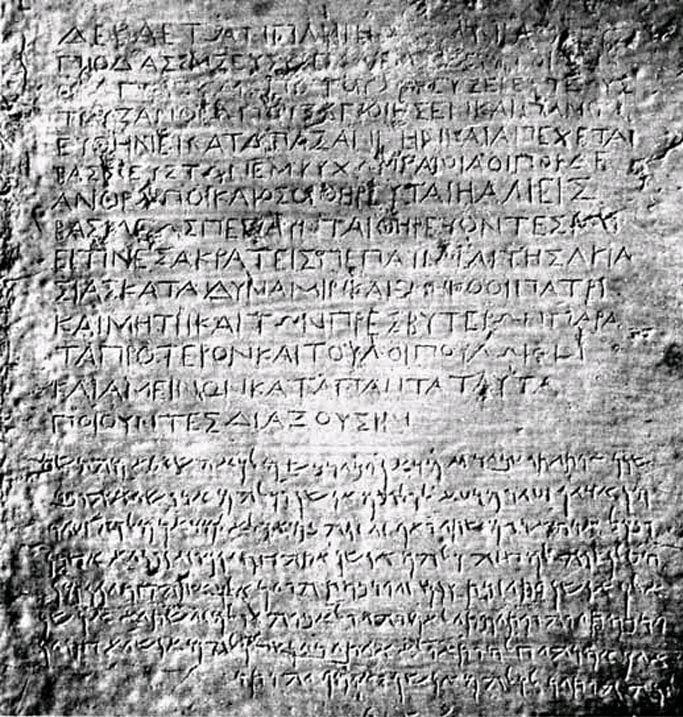

- Language and Script of Inscriptions: Most of Ashoka's inscriptions are in the Prakrit language and Brahmi script. Inscriptions at Mansehra and Shahbazgarhi are in Prakrit and Kharoshthi script. There are also inscriptions in Greek and Aramaic, including a bilingual Greek-Aramaic inscription found at Shar-i-Kuna near Kandahar in Afghanistan. Aramaic inscriptions were discovered at Laghman, Taxila, and a bilingual Prakrit-Aramaic inscription was found at Lampaka and Kandahar.

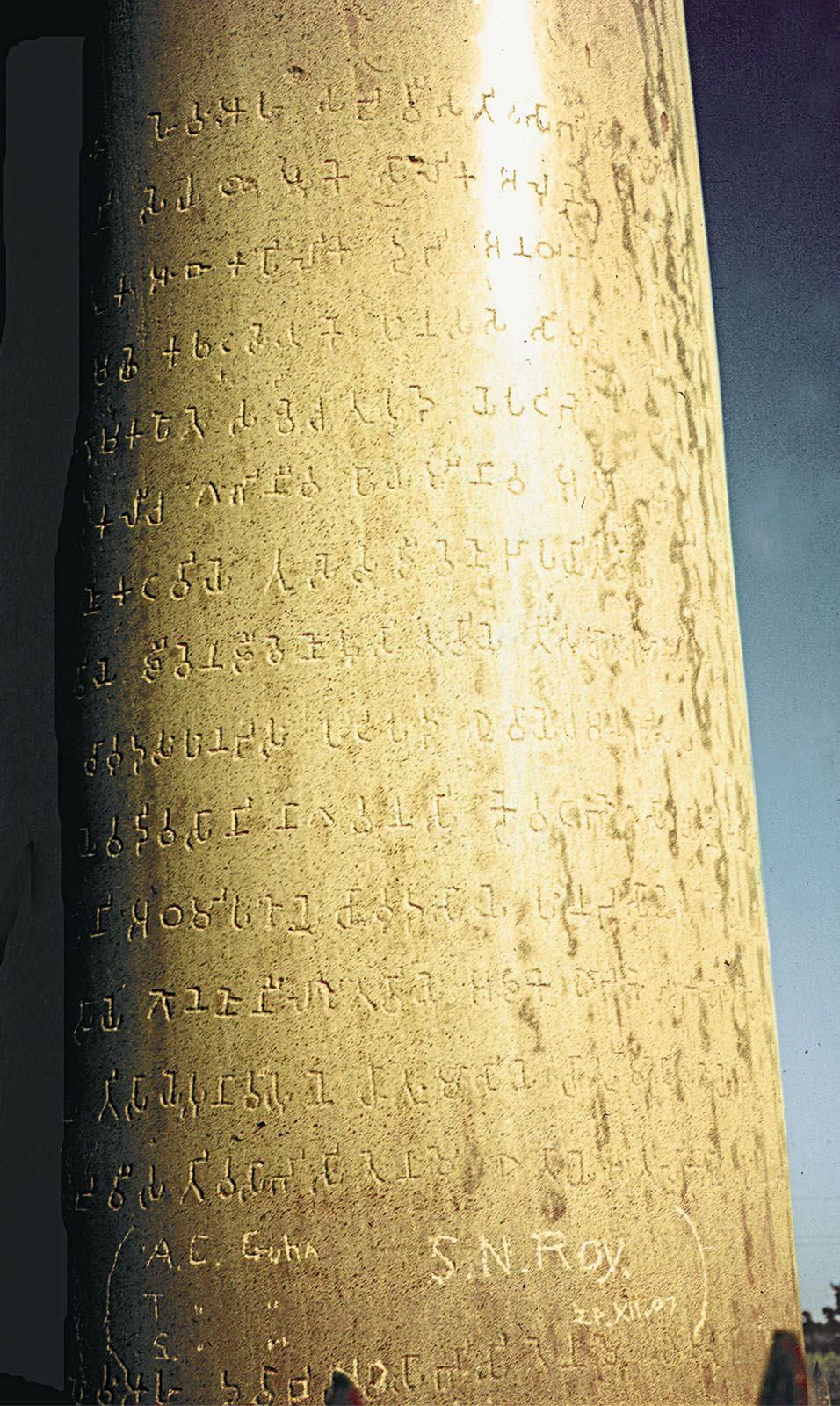

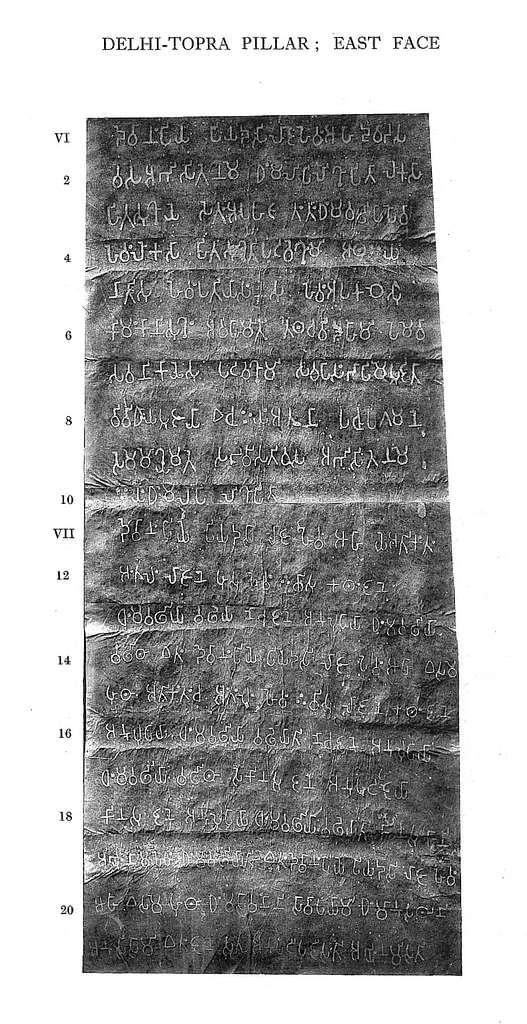

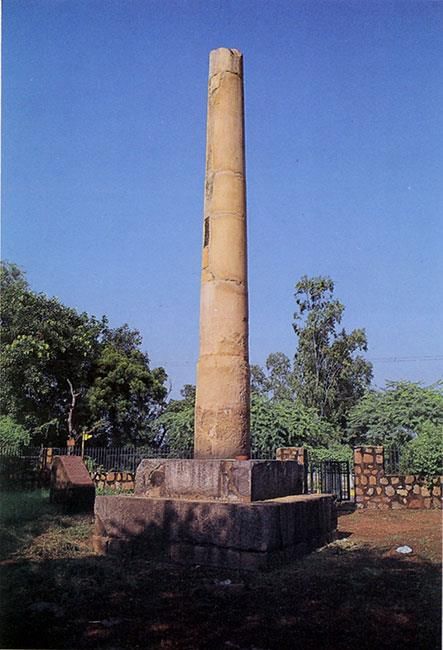

- Categories of Ashoka's Inscriptions: Ashoka's inscriptions are categorized into 14 major rock edicts and 6 (or 7) pillar edects. These edicts occur in different places with minor variations. There are also several minor rock edicts, minor pillar edicts, and cave inscriptions. The minor rock edicts are considered among the earliest inscriptions, followed by the major rock edicts and then the pillar edicts. Some inscriptions reference events based on the number of years since Ashoka's abhisheka (consecration ceremony).

- Unique Voice of Ashoka's Edicts: What makes Ashoka's edicts unique is that they reflect his personal voice and ideas, unlike royal inscriptions from later times that followed a conventional pattern and phraseology.

Inscription on Delhi-Topra Pillar

- Ashoka's inscriptions primarily focus on explaining dhamma, the king's efforts to promote it, and his self-assessment of his success. Some inscriptions directly reflect his loyalty to the Buddha's teachings and his close ties with the sangha (Buddhist community). While these inscriptions provide valuable insights into Ashoka's perception of his role as king, they offer limited and indirect references to other aspects like administration or the social and economic conditions of the Maurya period.

- Later inscriptions, such as the Junagarh/Girnar inscription of Rudradaman from 150 CE, mention projects like the Sudarshana lake, which was initiated during Chandragupta Maurya's time and completed under Ashoka. Inscriptions from the 5th to 15th centuries CE in Shravana Belgola, Karnataka, reference an ascetic named Chandragupta and the Jaina saint Bhadrabahu, suggesting a connection to the Maurya king, although this is a debated topic.

Inscriptions on Famine Relief

Sohgaura Inscription:

- Discovered in 1893 in Sohgaura village, Uttar Pradesh.

- Bronze plaque measuring 6.4 × 2.9 cm, inscribed in Prakrit language and Brahmi script.

- Issued by mahamatras (officials) of Shravasti from Manavasiti.

- Ordered distribution of supplies from storehouses during drought.

- Storehouses included Triveni, Mathura, Chanchu, Modama, and Bhadra.

- Scholarly Opinions:

- Scholars debate pre-Ashokan or post-Maurya date, with majority favoring post-Maurya.

- K. P. Jayaswal linked inscription to Jaina legend of famine during Chandragupta's reign, but this interpretation is speculative.

Mahasthan Inscription:

- Discovered in 1931 by Baru Faqir in Mahasthangarh, Bangladesh.

- Fragmentary inscription on limestone, 8.9 × 5.7 cm, with 7 lines.

- Language and script similar to Ashokan inscriptions, but dating is disputed.

- Likely issued by a ruler to mahamatra in Pundranagara (Mahasthangarh) to relieve famine.

- Mentioned advancing loans in coins (gandakas) and distributing paddy (dhanya) from granary.

- Aimed to help Samvamgiyas group during famine.

- Expected repayment of coins and paddy to treasury post-recovery.

Archaeological and Numismatic Evidence

- Archaeological investigations during the Maurya period are limited, and reliable dates are scarce. Consequently, there is minimal information about the middle and late phases of the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) in the Ganga valley, which roughly aligns with the Maurya period. Information about sites outside the Ganga valley is even more limited.

- Archaeological remains from Kumrahar and Bulandibagh, linked to Pataliputra, the Maurya capital, indicate a greater diversity of artifacts and enhanced urban features during the Maurya period compared to earlier levels. Other significant sites from this period include Taxila, Mathura, and Bhita. The material evidence from the Maurya period includes Ashoka’s pillars and various sculptural and architectural elements, many of which were products of royal patronage. Additionally, stone sculptures and terracotta images reflecting a popular urban culture have been found.

- During the Maurya period, punch-marked coins, primarily made of silver, continued to be issued and used. Symbols such as the crescent-on-arches, tree-in-railing, and peacock-on-arches became associated with the Maurya kings. The exact meaning and significance of these symbols are often unclear.

- Some may have been part of a common pool of cultural symbols, while others, like the sun, could have been symbols of royalty or held religious significance. For example, the tree-in-railing symbol might represent the Buddha’s enlightenment, and the arch symbols could signify a stupa. However, these interpretations are speculative.

- The use of symbols on state-issued coins would have given them political significance. The Arthashastra mentions different denominations of silver coins called panas and copper coins called mashakas.

The Maurya Dynasty

The Maurya Empire was founded by Chandragupta Maurya, who overthrew the Nanda dynasty. Chandragupta (324/321–297 BCE), his son Bindusara (297–273 BCE), and grandson Ashoka (268–232 BCE) were the first three rulers. Under Ashoka, the empire reached its height, and it continued under later Mauryas until 187 BCE.

- According to Buddhist texts, the Mauryas were Kshatriyas from Pipphalivana. Different sources provide various accounts of Chandragupta's origins, some suggesting low social status, while others claim he was of noble birth. Early medieval writers described him as the son of a Nanda king.

- Chandragupta likely began in Punjab and moved east to conquer Magadha, facing the Nandas. He is traditionally said to have received help from Chanakya, a Brahmin from Taxila.

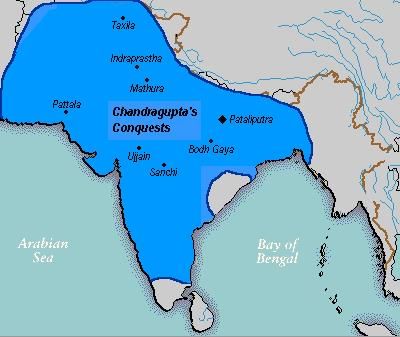

- This period followed Alexander the Great's invasion (327–326 BCE). Greek sources mention Chandragupta meeting Alexander and later clashing with Seleucus Nicator, Alexander’s successor. Around 301 BCE, they reached an agreement where Chandragupta gained territories in present-day Afghanistan and Baluchistan in exchange for 500 elephants. The specifics of a potential matrimonial alliance are unclear.

The Delhi-Meerut Pillar

- The 2nd-century CE Junagarh inscription of Rudradaman is the only clear historical reference to Chandragupta Maurya. It credits him with initiating the construction of the Sudarshana lake during his reign. By the time of Ashoka, the Maurya Empire had expanded into Karnataka, likely due to major conquests by Chandragupta years earlier.

Sangam Poetry and Maurya Involvement

- A poem by the Sangam poet Mamulanar in the Akananuru (Akam 251) narrates how the Koshar, a southern power, faced challenges from the Mokur, leading the Moriyas to assist them.

- Another poem (Akam 281) depicts the Vadugar, meaning 'northerners,' as part of the Maurya army's southern march.

- If these references are historically accurate, they imply that the Mauryas were involved in southern politics, had an alliance with the Koshar, and included Deccani troops in their army.

Chandragupta, Jainism, and Karnataka

Later inscriptions and Jain texts suggest a link between Chandragupta Maurya, Jainism, and Karnataka. Places in the Shravana Belgola hills bear the suffix 'Chandra,' and Jain tradition recounts Chandragupta's association with the Jaina saint Bhadrabahu.

- According to this tradition, Chandragupta accompanied Bhadrabahu to Karnataka to escape a predicted 12-year famine in Magadha and later practiced sallekhana, a ritual death by starvation.

- This story is found in later texts like the Brihatkathakosha of Harishena and the Rajavalikathe. Inscriptions in the Shravana Belgola hills from the 5th to 15th centuries CE mention Chandragupta and Bhadrabahu.

- While it is possible that there is a historical basis for the Jain tradition linking Chandragupta to Karnataka, it is not certain.

Chandragupta's Conquests: Graeco-Roman Perspectives

- Graeco-Roman sources, such as Plutarch and Justin, suggest that Chandragupta, known as Sandrocottus, conquered vast territories in India, with Plutarch claiming he subdued the whole of 'India' with an army of 600,000.

- The Junagarh inscription of Rudradaman supports the idea that Chandragupta's conquests reached as far as Saurashtra in Gujarat.

- While the exact meaning of 'India' by these writers is unclear, it is evident that Chandragupta played a crucial role in establishing the vast Maurya Empire.

Bindusara

Bindusara, the son of Chandragupta, ruled the Mauryan Empire from 297 to 273 BCE. There are varying accounts of his succession:

- Jaina Tradition : Suggests that Chandragupta abdicated in favour of his son Simhasena.

- Mahabhashya : Refers to Chandragupta’s successor as Amitraghata.

- Greek Accounts : Call Chandragupta’s successor Amitrochates or Allitrochates.

- Rebellion in Taxila : The Divyavadana mentions Ashoka, Bindusara’s son, quelling a rebellion in Taxila due to the misdeeds of corrupt ministers, possibly during Bindusara’s reign.

- Chanakya’s Conquests : Taranatha’s writings suggest that Chanakya, a prominent figure under Bindusara, subdued the nobles and kings of 16 towns, expanding Bindusara’s territory. Historians debate whether this indicates Bindusara’s conquests in the Deccan or the suppression of a revolt.

- Buddhist Sources : These sources provide limited information about Bindusara. One story suggests that an Ajivika fortune-teller predicted great things for Ashoka, Bindusara’s son, implying that Bindusara might have supported the Ajivika sect.

Greek Sources : Greek historians noted Bindusara’s diplomatic relations with western kings. For instance:

- Strabo : Reports that Antiochus, the king of Syria, sent an ambassador named Deimachus to Bindusara’s court.

- Pliny : Mentions that Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Egypt, sent an ambassador named Dionysius to Bindusara.

- Anecdote : There is a story of Bindusara asking Antiochus to send him sweet wine, dried figs, and a sophist. Antiochus allegedly responded that while he could send the wine and figs, Greek laws prohibited the buying of a sophist.

- Sanchi Inscription : A fragmentary inscription at Sanchi, possibly referring to Bindusara, suggests a connection between the king and this Buddhist site.

- Death and Succession Conflict : Bindusara died in 273 BCE, leading to a four-year succession struggle. The Divyavadana claims that Bindusara wanted his son Susima to succeed him, but his ministers supported Ashoka. The Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa texts describe Ashoka as killing 99 of his brothers, sparing only Tissa.

- Ashoka’s Reign : Ashoka ruled from c. 268 to 232 BCE. Buddhist texts portray him as an ideal king due to his close association with Buddhism. However, these accounts may not be objective, so it’s important to approach them with caution.

- According to the Ashokavadana, Ashoka's mother was a queen named Subhadrangi, who was the daughter of a Brahmana from Champa. Due to a palace intrigue, she was initially kept away from the king. However, this situation eventually changed, and she gave birth to a son.

- The child was named Ashoka, which means "without sorrow," based on his mother's exclamation at his birth. The Divyavadana also tells a similar story but names the queen Janapadakalyani in one version. The Vamsatthapakasini refers to her as Dharma. During his father's reign, Ashoka served as the governor of Ujjayini, and possibly Taxila before that, although he might have gone to Taxila to suppress a revolt.

- The Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa narrate the love story of Ashoka and Devi, the daughter of a merchant from Vidisha. Devi later became the mother of Ashoka's renowned children, Mahinda and Sanghamitta, who eventually joined the Buddhist sangha. Other queens mentioned in various texts include Asandhimitta, Tissarakhita, and Padmavati. An inscription on the Allahabad–Kosam pillar records gifts made by queen Karuvaki.

Legends of Ashoka

Ashoka's fame was initially based on legendary accounts of his life found in Buddhist texts like the Ashokavadana, which was part of the Divyavadana. This text, believed to have been composed by monks in the Mathura region, contains stories about Ashoka that were likely passed down orally before being written down. Mathura was a significant center for Buddhism, particularly the Sarvastivada school.

- One story from the Ashokavadana tells of a boy named Jaya in a previous life who met the Buddha. Jaya offered a handful of dirt to the Buddha, wishing to become a king and a follower of the Buddha in the future. The Buddha smiled at the boy's gesture, indicating that he would become a great emperor in his next life, ruling from Pataliputra.

- Another legend depicts Ashoka's rise to power, portraying him as initially disliked by his father, Bindusara, due to his appearance. Ashoka allegedly tricked the legitimate heir to the throne and gained a reputation for cruelty, earning the nickname 'Ashoka the Fierce.' He tested his ministers' loyalty, executing many, and even built a torture chamber for his amusement. His transformation into 'Ashoka the Pious' reportedly began after an encounter with a Buddhist monk. Xuanzang, a 7th-century traveler in India, mentioned visiting the site of Ashoka's infamous torture chamber.

- According to the Ashokavadana, Ashoka's final days were marked by his intense desire to give away everything he had to the Buddhist sangha. Initially, he started distributing state resources, but his ministers, worried about depleting the treasury, denied him access. Undeterred, Ashoka turned to his personal belongings, giving them away one by one. Eventually, he was left with only a single myrobalan fruit, which he also offered to the sangha. After giving away everything he owned, Ashoka passed away peacefully.

- John S. Strong emphasizes that when analyzing such legends, it is important to consider that the authors reworked old stories and traditions, some of which were previously shared orally.

- Their goal was to reinforce the faith of existing believers and attract new followers to Buddhism. These legends aimed to convey essential ideas such as the nature of suffering, the concept of karma and rebirth, and the importance of devotion to the Buddha. They also highlighted the benefits of generous giving to the sangha and the role of kingship in supporting the Buddhist faith.

- Buddhist legends, like those found in the Ashokavadana, played a significant role in shaping Ashoka's image as an exemplary Buddhist king. This reputation garnered him admiration and emulation not only in the Indian subcontinent but also in East Asia.

The Stone Portrait of Ashoka at Kanaganahalli

- In 1993, archaeologists surveying the area around Sannati in Karnataka discovered the remains of a large brick stupa encased with sculpted limestone slabs at Kanaganahalli. The site, located on the left bank of the Bhima River, revealed numerous artifacts, including carved limestone slabs, pillars, railings, capitals, and over 60 lead coins bearing the names of Satavahana kings.

- An important find was a broken relief sculpture depicting a king and queen, with an inscription reading ‘Ranyo Ashoka’ (king Ashoka), which confirmed the identity of the central figure as Ashoka. Further excavations in 1996-97 provided valuable material illustrating the history of Buddhism in the upper Krishna area during the early centuries CE.

The Maurya Empire and Ashoka’s Inscriptions

Ashoka’s inscriptions indicate the vast extent of the Maurya Empire, stretching from Kandahar in the northwest to Orissa in the east. The empire encompassed almost the entire subcontinent, excluding the southernmost regions inhabited by the Cholas, Pandyas, Keralaputras, and Satiyaputras. Ashoka is renowned for his association with Buddhism and his pacifist ideals, as reflected in Buddhist texts and his own inscriptions.

Decline of the Maurya Empire

- The Maurya empire experienced a rapid decline after the reign of Ashoka.

- Later Maurya rulers are mentioned in the Puranas, indicating they had relatively short reigns.

- The empire weakened and fragmented, possibly due to an invasion by the Bactrian Greeks.

- The Maurya dynasty ended when the last king, Brihadratha, was killed by his military commander Pushyamitra around 187 BCE, who then founded the Shunga dynasty.

Literary and Archaeological Profiles of Cities

- During the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE, agrarian and urban expansion continued, with cities growing in size and complexity.

- Urbanism spread to new areas such as Kashmir, Punjab, lower Ganga valley, Brahmaputra valley, and Orissa, with noticeable urban growth in the far south as well.

- The relationship between the Maurya empire's expansion and urban development is complex; while the Maurya impact is significant, it should not be overstated.

- Urban growth was linked to the expansion of specialized crafts, trade, and guild organization, with money increasingly used as a medium of exchange.

- Contrary to Megasthenes’ account, evidence shows that money-lending with interest was practiced in earlier times.

- The Maurya period marked the beginning of royal inscriptions on stone, indicating the use of writing for various activities, including business transactions.

- Developments from middle and late Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) levels at various sites reflect these changes.

Urban Centers and Pataliputra

- Greek sources provide information about Pataliputra, the capital of Magadha, during the Maurya period.

- Megasthenes described Pataliputra as a city surrounded by a wooden wall with towers and arrow slits, protected by a moat.

- Archaeological evidence supports some aspects of Megasthenes’ account, although the precise location and extent of ancient Pataliputra remain debated.

- Remains from the Maurya phase of Pataliputra have been found in modern Patna, particularly at Kumrahar and Bulandibagh.

- At Kumrahar, a pillared hall with 80 pillars arranged in 10 rows has been discovered, while Bulandibagh features remains of a wooden palisade, possibly representing the fortifications described by Megasthenes.

Pataliputra and the Palace: Insights from Arrian and Aelian

- According to ancient sources, the number of cities in India is vast and cannot be precisely counted.

- Cities located along rivers or the coast are typically built of wood due to the destructive nature of heavy rains and river floods.

- In contrast, cities on elevated land are constructed from brick and mud.

- Pataliputra, the largest city in India, lies where the Erannoboas (Son) River and the Ganges River meet.

- The Ganges is the biggest river in India, while the Erannoboas, though smaller than the Ganges at their confluence, is one of the largest rivers in India.

- Megasthenes, an ancient historian, describes Pataliputra as being 80 stadia (over 9 miles) long and 15 stadia (about 1¼ miles) wide, surrounded by a ditch 6 plethora wide and 30 cubits deep.

- The city’s wall is fortified with 570 towers and has 64 gates.

The Royal Palace in India

- The Indian royal palace, home to the greatest king in the country, is described as more impressive than the famed Persian cities of Susa and Ekbatana.

- The palace features parks with tame peacocks and pheasants, as well as various cultivated plants that are carefully tended by the king’s servants.

- The palace grounds include shady groves and pastures filled with trees, some native to India and others brought from different regions, all of which are always in bloom and never shed their leaves.

- Notable birds, such as parrots, which are sacred in Indian culture and believed to imitate human speech, freely roam the palace grounds.

- The palace also boasts artificial ponds filled with large, tame fish, which only the king’s sons are allowed to fish as a form of play and learning.

Schematic Plan of a Royal Palace, Based on the Arthashastra

Archaeological Findings in the Maurya Empire

Excavations at various sites have provided insights into urban life during the Maurya Empire. One significant find was at Stratum II of the Bhir mound in Taxila, which dates back to the 3rd century BCE.

- Settlement Layout: The layout of the settlement was irregular, with a mix of streets and lanes. Four streets and five lanes were identified, with a broad street (6.70 m wide) that was not straight. Other streets ranged from 3 to 5 m in width and were often winding. Lanes leading off the streets were narrower but more regularly aligned.

- Civic Planning: Some level of civic planning was evident from the presence of round refuse bins in open squares and streets. Covered drains were found in some areas, but not in the main street. Rough stone pillars (about 0.91 m high) at house corners protected against damage from passing carts and chariots.

- Housing Structure: Houses typically had rooms arranged around an open courtyard, often paved with stone. Larger houses had two courtyards. Bathing areas and open passages were also stone-paved. Sewage was managed through stone surface drains and earthenware drain-pipes leading to soak-pits.

- Evidence of Shops: Some excavated rooms may have been shops. One room containing cut pieces of shell and mother-of-pearl was identified as a shell worker's shop. A larger complex identified as a religious structure included about 30 rooms, two courtyards, and a large pillared hall, possibly used for cult activities.

- Ropar and the Indo-Gangetic Divide: The site of Ropar shows a transition from village to town life during Period III (c. 600–200 BCE). Evidence includes Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), punch-marked and uninscribed cast copper coins, and a seal with an inscription in Maurya Brahmi. Houses were constructed of stone set in mud mortar, with some built of mud-brick and burnt brick. A 12 ft wide wall of burnt brick, possibly leading to a rainwater storage tank, was also found. Upper levels revealed soak-pits lined with terracotta rings. Maurya period levels have been discovered at the Purana Qila in Delhi as well.

In the upper Ganga valley, remnants of a fortified settlement from the Maurya period were found at Bhita. Excavations led by John Marshall in 1915 focused on the southeastern part of the site, where he discovered two streets: High Street and Bastion Street.

- High Street was about 9.14 meters wide and likely connected to a series of gates with guardrooms.

- Bastion Street, the narrower of the two, was located to the northeast.

- The fortifications included a 3.40-meter thick mud rampart, a circular bastion, and a gateway that had been blocked at some point.

- One of the notable findings was a house dubbed the ‘House of the Guild’ by Marshall, due to the discovery of a seal with the word nigama. This house had 12 rooms arranged around a rectangular courtyard and might have been two stories high, undergoing several reconstructions.

- Similar houses with rows of rooms facing the road and platforms or verandahs in front were also found.

- Cunningham linked Bhita to a place called Bitbhaya-pattana mentioned in Jaina texts, while Marshall associated it with Vichhi or Vicchigrama, a name found on a seal at the site.

- Regardless of these identifications, the large number of seals discovered indicates that Bhita was likely an important trade center.

Storage Jars in Ancient Settlements

Mathura and Sonkh: Early Urbanization

- Mathura: Evidence of occupation during the Maurya period, with urbanization beginnings noticeable in Period II (late 4th century BCE to 2nd century BCE).

- Pottery: Marked by Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW).

- Settlement Size: Expanded to about 3.9 sq km, with a mud fortification wall on three sides and the Yamuna River to the east.

- Crafts: Specialized crafts flourished, including terracotta figurine manufacturing, copper and iron working, and bead making.

- Coins: Early evidence of coins, including uninscribed cast and die-struck coins and silver punch-marked coins.

- Sonkh: Similar findings to Mathura, with NBPW, terracotta figurines, and various types of coins.

Atranjikhera: Detailed Findings

- NBPW sub-phase IVC (c. 350–200 BCE): Marked by increased structural activities and development in various aspects.

- Defences: Mud rampart topped by a brick parapet, indicating a period of structural enhancement.

- Terracotta Art and Coinage: Development of terracotta art and coinage, along with the first evidence of writing.

- Structural Phases: Five structural phases identified, each with distinct features and activities.

- First Structural Phase: Mud-brick walls, mud floors, ring well, and circular barn.

- Second Structural Phase: Mud-brick walls and terracotta ring barn.

- Third Structural Phase: Increased building activity, including walls and working floors for a room and granary.

- Granary: Divided into compartments with wattle-and-daub partitions, indicating storage practices.

- Kitchen: Features a three-mouthed hearth (chullah) and various pots and pans, suggesting cooking activities.

- Fourth Structural Phase: Mud-brick and burnt brick walls with mud floors.

- Fifth Structural Phase: Mud-brick and mud walls with thick mud plaster and an oval fire pit.

- Rampart Repairs: Mud rampart damaged by floods, repaired and raised, indicating ongoing maintenance.

The Bhita Mound

The Bhita Mound, located in the Banda district of Uttar Pradesh, is an archaeological site that has yielded a significant collection of terracotta artefacts spanning different historical periods. This site is particularly noted for its terracotta figurines, which provide valuable insights into the artistic and cultural practices of the people who inhabited the region.

- Period IVC: During this period, the terracotta artefacts from Bhita included a well-crafted female bust, a damaged plaque featuring an ornamented female figure, and part of a moulded plaque depicting a human figure. Animal figurines from this period included representations of a bull, horse, elephant, goat, and some indeterminate figures. Bird figurines included what appeared to be a kite, duck, and peacock. Other terracotta objects from this period included wheels, rattles, gamesmen, bangles, a skin rubber, quern, dabber, and net sinker.

- Notable discoveries included terracotta playing balls with intricate incised lines, discs with impressed or incised notches, and a terracotta design block possibly used for printing designs on cloth. Terracotta crucibles for melting metal, a miniature pot, votive tanks, and an inscribed sealing with a Brahmi legend were also found.

- Various beads made from semi-precious stones, a glass bead, and stone objects such as a pestle, grinder, and broken quern were among the findings. Bone and ivory objects included arrowheads, stylii, an ivory bead, and an ivory ear stud. Iron and copper artefacts were also discovered, along with coins and a bone sealing with a Brahmi letter and svastika symbol.

- Fortified Sites and Ramparts: In the middle Ganga valley, fortified sites such as Shravasti, Vaishali, and Tilaura-kot were established around the late 3rd to 2nd century BCE. In the lower Ganga valley, Mahasthangarh, identified with ancient Pundravardhana, yielded a Brahmi inscription, indicating its historical significance. The brick rampart at Bangarh, associated with ancient Kotivarsha, dates to the 2nd century BCE, along with the mud ramparts of Chandraketugarh, which likely belong to the same period.

- Chandraketugarh, dating from the pre-Maurya period, has produced rich antiquities, particularly exquisite terracottas, although its archaeological profile remains unclear. Tamluk, an important early historical port and the eastern terminal of the Uttarapatha, is connected to mid-NBPW levels in the Ganga valley through NBPW, terracottas, and other antiquities.

Historical Sites in Ancient India

Orissa

- Sisupalgarh : Located near Bhubaneswar, possibly the ancient site of Tosali. Featured a mud fortification from the early 2nd century BCE, roughly square in shape, covering about 3/4 mile on each side. Evidence of habitation outside the fort from around 300 BCE to 350 CE.

- Jaugada : Situated on the Rishikulya River. Period I showed post-holes, floors made of rammed earth or gravel, and evidence of bead making, potentially dating to at least the 3rd century BCE.

Rajasthan

- Bairat : Identified as ancient Viratanagara, the capital of the Matsya kingdom. Excavations revealed remains from the Maurya and post-Maurya periods, including pillars, structures like a Buddhist monastery, and various antiquities.

- Rairh : Remains dated from the 3rd/2nd century BCE to beyond the 2nd century CE, including terracotta structures such as soak-pits.

- Sambhar : Occupation likely began in the 3rd/2nd century BCE, but detailed information is scarce.

Gujarat

- Early historical phase indicated by the presence of Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) at sites like Broach, Nagal, Prabhas Patan, and Amreli, dating to the early 3rd century BCE.

- Broach : Limited excavations revealed a thick deposit with evidence of bead manufacture, including finished and unfinished beads of semi-precious stones.

- Coastal sites in Gujarat gained importance for trade in subsequent centuries.

Central India

- Ujjayini (Ujjain) : Headquarters of a Maurya province. Period II featured NBPW, copper coins, bone and ivory points, terracotta ring wells, and ivory seals with early Brahmi inscriptions, likely dating to the Maurya period.

- Besnagar (Vidisha) : Rampart built in the 2nd century BCE enclosing about 240 hectares.

Maharashtra

- Tagara (Ter) : Earliest level with NBPW and black-and-red burnished pottery, dating to the 3rd–2nd centuries BCE, indicating early urbanism.

- Sopara : Site of Ashokan rock edicts, suggesting its importance as a port during Maurya times, although not extensively explored.

- Further south in India, sites like Sannati, Kondapur, and Madhavpur appear to have been occupied during the Maurya period. Ashokan edicts have been discovered at Maski and Brahmagiri, but there is no information available about the settlements in these areas during that time.

- Amaravati, known in ancient times as Dhanyakataka and located on the banks of the Krishna River, has produced a fragmentary inscription in Maurya Brahmi. The earliest phase of settlement at Amaravati, referred to as Period I, dates back to at least the 4th century BCE.

- This period was characterized by the presence of Black Red Ware (BRW) and Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW). Potsherds bearing Brahmi inscriptions, similar to those found in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, were also discovered at Amaravati. This type of pottery continued into Period Ib, which also marks the beginning of the stupa complex and the discovery of an inscribed stone slab. The settlement of Uraiyur may have origins dating back to the 3rd century BCE.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Power and Piety: The Maurya Empire, c. 324–187 BCE - 1 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What were the major contributions of Ashoka during the Maurya Period? |  |

| 2. What is the significance of the Delhi-Meerut Pillar in understanding the Maurya Empire? |  |

| 3. How did Jainism influence Chandragupta Maurya's rule? |  |

| 4. What is the importance of Ashoka's inscriptions in understanding the Maurya Empire? |  |

| 5. What archaeological findings related to the Maurya Empire have been discovered at the Bhita Mound? |  |