Interaction and Innovation, c. 200 BCE–300 CE - 2 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

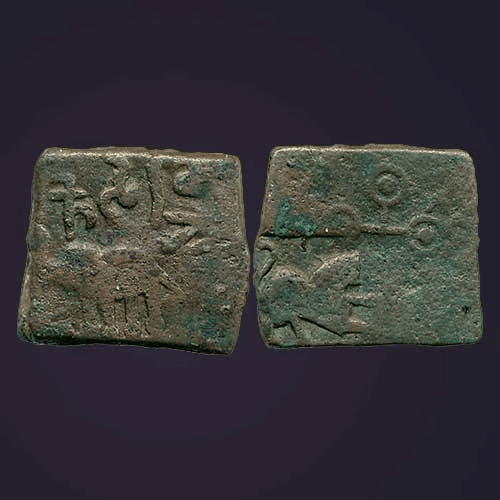

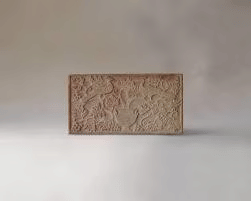

Copper Coin of Vasishtiputra Pulumavi, Satavahana Dynasty

Early History and Origin of Satavahanas

- Historians debate whether the Satavahanas first gained power in the eastern or western Deccan region of India.

- The Puranas refer to them as Andhras, suggesting they were either based in the Andhra region or belonged to the Andhra tribe.

- The term Andhra-bhritya in the Puranas is interpreted by some as indicating that the Satavahanas were subordinates of the Mauryas.

- However, others argue it could mean "servants of the Andhras", potentially referring to the Satavahanas' successors.

Evidence of Eastern Deccan Origin

- The discovery of early Satavahana coins at Kotalingala and Sangareddy in the Karimnagar district of Andhra Pradesh supports the idea that the Satavahanas began their rule in the eastern Deccan.

Evidence of Western Deccan Origin

- Inscriptions found in the Naneghat and Nashik caves indicate the western Deccan as the original home of the Satavahanas.

- Some historians believe the Satavahanas initially established their power around Pratishthana (modern Paithan) in the western Deccan before expanding into the eastern Deccan, Andhra, and the western coast.

The Satavahana Dynasty

The Satavahana dynasty ruled a large part of western and central India from around 200 BCE to 200 CE. They are known for their early use of coins and their patronage of Buddhism and Hinduism. The dynasty played a crucial role in the trade and cultural exchange between the western and eastern parts of India.

- Simuka: The founder of the Satavahana dynasty, Simuka, established the rule in the Deccan region.

- Kanha: Succeeded Simuka and expanded the empire westward, reaching areas like Nashik.

- Satakarni I: The third king, known for his long reign of about 56 years and for being referred to as the lord of Dakshinapatha in inscriptions.

- Hala: The 17th king of the dynasty, credited with composing the Gatha Sattasai, a famous collection of 700 erotic poems in the Maharashtri Prakrit dialect.

The Satavahana empire eventually covered modern-day Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra, with occasional control over parts of northern Karnataka, eastern and southern Madhya Pradesh, and Saurashtra. The Roman author Pliny mentioned the Andhra country as being prosperous, with many villages and 30 walled towns, and noted its strong military, including 100,000 infantry, 2,000 cavalry, and 1,000 elephants.

The exact starting date of the Satavahana rule is debated, but the sequence of rulers is relatively certain. Simuka was the founder, followed by his brother Kanha, and then Satakarni I. Some inscriptions and historical accounts suggest that Satakarni I had conflicts with other regional powers, such as the Chedi king Kharavela, who claimed to have defeated a king named Satakarni in his second year of reign. The Satavahanas were also known to have conquered western Malwa and were recognized as powerful rulers in the Deccan region.

- Conflict and Control: The Satavahanas and Shakas were in a long-standing struggle, particularly over control of important ports like Bhrigukachcha (Broach), Kalyan, and Suparaka (Sopara).

- Rise of the Kshaharata Kshatrapas: The Kshaharata Kshatrapas initially expanded at the expense of the Satavahanas.

- Gautamiputra Satakarni: Gautamiputra Satakarni revitalized the Satavahana Empire, bringing it to its peak. His achievements are praised in an inscription by his mother, Gautami Balashri, at Nashik.

- Victories and Restorations: Gautamiputra is credited with defeating the Shakas, Pahlavas, and Yavanas, uprooting the Kshaharatas, and restoring the Satavahana glory.

- Defeating Nahapana: He defeated Nahapana and recovered territories lost to the Shakas.

- Land Grants and Control: Inscriptions from Nashik and Karle indicate his control over regions like Pune and land grants to Buddhist monks.

- Coins and Influence: Gautamiputra’s coins were found as far as the eastern Deccan, and he re-struck Nahapana’s coins, indicating his influence.

- Extent of Rule: His rule extended from Malwa and Saurashtra in the north to the Krishna in the south, and from Berar in the east to Konkan in the west.

- Claims of Conquest: The statement about his horses drinking from the three oceans reflects claims of extensive conquests in trans-Vindhyan India.

- Final Years: Towards the end of his reign, Gautamiputra may have lost some territories to the Kardamakas that he had previously conquered from the Kshaharatas.

Copper Coins of Satakarni I

Coins from the time of Vasishthiputra Pulumayi, who succeeded Gautamiputra, have been discovered in various locations across Andhra Pradesh. It's believed that due to his focus on the eastern regions, the Shakas may have regained some of their lost territory during this period.

Yajnashri Satakarni: An Overview

- Yajnashri Satakarni was a significant king of the Satavahana dynasty.

- His coins feature images of ships, some with a single mast and others with two masts.

- This suggests that he was involved in maritime activities and trade.

- Yajnashri Satakarni appears to have continued the struggle against the Shakas, indicating ongoing conflicts during his reign.

- He is likely regarded as the last king of his dynasty to effectively control both the eastern and western regions of the Deccan.

Successors of Yajnashri Satakarni

- The kings who followed Yajnashri Satakarni included:

- Gautamiputra Vijaya Satakarni

- Chanda Satakarni

- Vasishthiputra Vijaya Satakarni

- Pulumavi

Later Satavahana Rulers

- Some of the later rulers of the Satavahana dynasty are not listed in the Puranic king-lists and are known only through their coins.

- This indicates that these rulers may have had a less prominent historical record but still played a role in the dynasty's history.

End of the Satavahana Dynasty

- The Satavahana dynasty is believed to have ended in the mid-3rd century CE.

- Following the breakup of the empire, several new powers emerged in the Deccan and surrounding regions, including:

- Vakatakas in the Deccan

- Kadambas in Mysore

- Abhiras in Maharashtra

- Ikshvakus in Andhra

Satavahana Claims and Political Legitimacy

- The Satavahana rulers claimed descent from Brahmanas and aligned themselves with the Brahmanical Vedic tradition.

- An inscription from Nashik, attributed to Gautami Balashri, describes Gautamiputra Satakarni as a "peerless Brahmana" who humbled the pride of the Kshatriyas.

- This suggests that the Satavahana kings used their Brahmanical credentials to legitimize their rule.

- References to Satakarni I performing great Vedic sacrifices in another inscription indicate that such rituals were important for acquiring political legitimacy.

Use of Matronyms

- The use of matronyms (names derived from mothers) by Satavahana kings is noteworthy.

- However, it does not provide evidence of a matriarchal or matrilineal system within their society.

Administrative Structure and Local Rulers

- Despite their title as "Lord of Dakshinapatha," it is believed that the Satavahanas did not fully integrate the entire Deccan administratively.

- Like the Shakas and Kushanas, they had subordinate chiefs and rulers who recognized their political authority.

- Local rulers known as maharathis and mahabhojas, who had emerged before the Satavahana period, were incorporated into the Satavahana polity.

- These families, such as the Kuras, Anandas, and maharathi Hasti, continued to be influential even after the establishment of Satavahana rule.

- The Satavahana empire was divided into large administrative units called aharas.

- Various officials, including amatyas, mahamatras, and mahasenapatis, were responsible for governance, along with scribes and record keepers.

- Villages were managed by village headmen (gramikas) who played a crucial role in local administration.

Introduction

In the early period of land grants, inscriptions from the Satavahana and Kshatrapa eras document royal gifts of land, often accompanied by tax exemptions.

Early Inscriptions and Land Grants

- Naneghat Inscription (1st century BCE): This inscription by Naganika mentions that villages were given as dakshina (offering) to priests during significant shrauta sacrifices, like the ashvamedha, performed by her husband, Satakarni I.

- Nashik Cave Inscription (2nd century CE): An inscription by Ushavadata describes the donation of 16 villages to the gods and Brahmanas. It also records the grant of a field to feed Buddhist monks residing in the cave.

- Inscription of Gautamiputra Satakarni: This inscription, also from the Nashik caves, documents the grant of a field to Buddhist monks. It specifies certain privileges and exemptions associated with the land, such as:

- Prohibition of entry or disturbance by royal troops

- Restriction on digging for salt

- Freedom from state officials' control

- Granting of various immunities (pariharas)

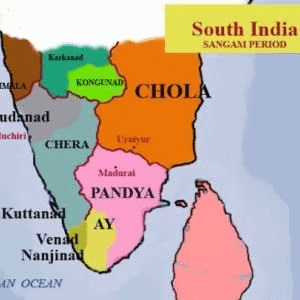

Kings and Chieftains in the Far South: The Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas

- The early historical period in South India is typically considered to have begun around the 3rd century BCE, although recent archaeological findings from Kodumanal suggest a possible earlier start, potentially in the 4th century BCE.

- The initial kingdoms of Tamilakam, situated between the Tirupati hills (Vengadam) and the southern tip of the peninsula, emerged in regions with rich agricultural potential, particularly suitable for rice cultivation.

Chola Kingdom

- Located in the lower Kaveri valley, roughly corresponding to modern Tanjore and Trichinopoly districts of Tamil Nadu.

- Capital at Uraiyur.

Pandya Kingdom

- Situated in the valleys of the Tamraparni and Vaigai rivers, aligning with present-day Tirunelveli, Madurai, Ramnad districts, and southern Travancore.

- Capital at Madurai.

Chera Kingdom

- Located along the Kerala coast.

- Capital at Karuvur, also known as Vanji.

Trade Networks

- All these kingdoms were active participants in the thriving trade networks of the period.

- Chola Ports: Puhar (Kaveripumpattinam) was the premier port.

- Pandya Ports: Korkai was the major port.

- Chera Ports: Tondi and Muchiri were important ports.

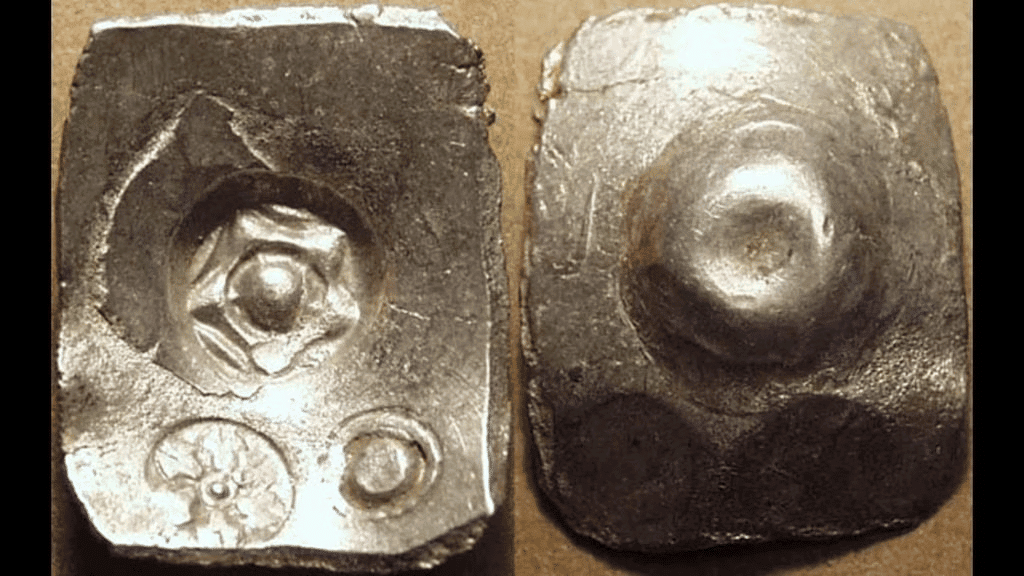

Punch-Marked Coins from Andhra and Pandya Country

- Rulers and Insignia: The Chera, Chola, and Pandya kings were known as vendar, meaning crowned kings. Each had specific insignia of royalty, such as the staff, drum, and umbrella. The emblems of power were also distinct: the tiger for the Cholas, the bow for the Cheras, and the fish for the Pandyas.

- Chieftains and Internecine Conflict: Besides the vendar, there were numerous chieftains known as velir. The period was marked by internecine conflict, with kings and chieftains often fighting against each other, forming alliances, and the lesser rulers paying tribute to the more powerful ones.

- Early Chera Kings:Udiyanjeral is recognized as the earliest known Chera king. His son, Nedunjeral Adan, is depicted as a formidable conqueror who defeated seven crowned kings and earned the title of adhiraja. His conquests were exaggerated to extend as far as the Himalayas, where he supposedly carved the Chera bow emblem. He engaged in battles against a Chola king, leading to the deaths of both adversaries.

- Expansion of Chera Power:Kuttuvan, the brother of Nedunjeral Adan, is credited with conquering Kongu and expanding Chera influence to the eastern and western oceans. One of Adan’s sons is described as an adhiraja who achieved military victories against chieftains such as Anji and led expeditions against rulers like Nannan in the Malabar region.

PANDYAS

Senguttuvan, another son of Adan, achieved victory over the Mokur chieftain. The Silappadikaram, a work from after the Sangam period, narrates his conquest of Viyalur in Nannan's territory and the capture of the Kodukur fortress in Kongu region. He played a significant role in a Chola succession dispute, supporting a claimant and eliminating nine rivals. Additionally, he fought an arya chieftain for stone to create an image of Kannaki, bathing in the Ganga before returning the stone to his land.

- Kudakko Ilanjeral Irumporai, one of the final Chera kings noted in Sangam literature, is reputed to have achieved victories against the Cholas and Pandyas. Another Chera ruler, Mandaranjeral Irumporai, who reigned in the early 3rd century CE, was captured by the Pandyas but later escaped and returned to his kingdom.

- Inscriptions from the 2nd century CE at Pugalur detail three generations of Chera princes from the Irumporai lineage, commemorating the construction of a rock shelter for a Jaina monk during the investiture of Ilankatunko, son of Perunkatunkon, and grandson of king Adan Cher Irumporai. The last ruler mentioned is identified with Ilanjeral Irumporai. Inscriptions from the 3rd century CE at Edakal in Kerala provide names of another branch of Chera kings.

- The Chola king Karikala is linked with numerous heroic deeds. A poem in the Pattuppattu narrates his early deposition and imprisonment, followed by his escape and restoration as king. Karikala is celebrated for defeating a coalition of Pandyas, Cheras, and their allies at the battle of Venni, where 11 rulers lost their drums, symbolizing royal power. The Chera king, wounded in battle, reportedly committed ritual suicide by starvation. Karikala's prowess is further highlighted by his victory at Vahaipparandalai, where several chieftains lost their umbrellas, another royal insignia. These victories indicate Karikala's dominance over contemporary monarchs and chieftains.

- Another notable Chola ruler is Tondaiman Ilandiraiyan, associated with Kanchi, either as an independent ruler or a subordinate of Karikala. A poet himself, one of his surviving songs underscores the importance of a king's personal character for effective governance. Later, the Chola kingdom experienced a prolonged and contentious conflict between two claimants to the throne—Nalangilli and Nedungilli.

Early Pandya Kings

- Nediyon, Palshalai Mudukudumi, and Nedunjeliyan are considered some of the earliest kings of the Pandya dynasty.

- Kovalan, the hero of the Silappadikaram , is believed to have died during the reign of Nedunjeliyan. This king reportedly died of remorse due to his involvement in the tragic events surrounding Kovalan's story.

- After this Nedunjeliyan, there was another king of the same name, who is famous for his military victories.

- This later Nedunjeliyan is said to have defeated a coalition of Cholas, Cheras, and five chieftains at a young age, capturing the Chera king in the process.

- Inscriptions from the early 2nd century BCE found in Mangulam, written in Tamil–Brahmi, record gifts made to Jaina monks by a subordinate and a relative of Nedunjeliyan.

- Scholar Mahadevan suggests that this Nedunjeliyan might have lived earlier than the two kings of the same name mentioned in Sangam literature.

- An inscription from around the 1st century BCE found in Alagarmalai mentions a figure named Kalu(Katu)mara Natan, who appears to have been a Pandya prince or subordinate based on his name.

The Royal Drum

The Relationship between Kings and Poets

This poem is one of many from the Sangam period that highlight the close bond between kings and poets.

- The Royal Drum (murachu) was an important symbol in the royal household. It was made from special materials and was associated with sacred power.

- The drum was beaten in the morning to wake the king, during battles, and on other special occasions.

- Desecrating the drum was considered a serious offense.

- In this poem, the poet Mochikirnarin praises Cheraman Takaturerinta Peruncheralirumporai, a king of the Chera dynasty.

- The poet describes how he accidentally climbed onto the royal drum and fell asleep on its soft, flower-covered surface. When the king arrived, instead of getting angry and punishing him, he gently fanned the poet until he woke up.

Tamil-Brahmi Inscriptions at Mangulam

Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions from the early centuries CE provide evidence of the excavation of caves for Jaina monks and nuns in Tamil Nadu. These inscriptions, found in various locations, indicate the dedication of these caves by kings, chieftains, and other individuals for the purpose of providing shelter and facilities for Jaina ascetics. The inscriptions typically list the names of the donors and the specific locations of the caves.

- The practice of excavating caves for Jaina monks and nuns reflects the growing influence and patronage of Jainism in Tamil Nadu during this period. Jainism, with its emphasis on asceticism and meditation, attracted a considerable following, and the establishment of cave monasteries provided a conducive environment for Jaina practitioners.

- These inscriptions not only shed light on the religious landscape of early historical Tamil Nadu but also highlight the role of local rulers and elites in supporting and promoting diverse religious traditions. The act of donating caves for Jaina monks and nuns signifies the importance of such ascetic practices in the socio-religious fabric of the time.

- According to Champakalakshmi (1996: 92–93), the urbanization during the Sangam period did not occur within the framework of a state polity. She argues that this era was characterized by tribal chiefdoms or, at best, 'potential monarchies.' Champakalakshmi suggests that the vendar (kings) had limited control over agricultural lands and relied on tribute and plunder for their sustenance. However, evidence of writing, advanced literature, urban centers, specialized crafts, and long-distance trade indicates otherwise.

- Poems from this period reference kings making lavish gifts of gold, gems, muslin, horses, and elephants, indicating their differential access to and control over resources. Kings were involved in long-distance maritime trade as consumers of luxury goods and played a role in developing trade ports, imposing tolls and customs. There is also clear evidence of dynastic coin issues.

- The existence of at least a rudimentary state structure in the case of the Chola, Chera, and Pandya monarchies is evident, even if these rulers did not have full control over the agrarian plains, a regular system of taxation, or a centralized coercive machinery.

Villages and Cities

Villages and Agriculture:

- Information about villages and agriculture in Tamilakam during the period is limited compared to what is known about cities.

- The Jatakas mention gamas (villages) ranging from 30 to 1,000 kulas (extended families).

- Some gamas are associated with specific occupational groups, such as reed workers (nalakaras) and salt makers (lonakaras).

- Villages of potters, carpenters, smiths, forest folk, hunters, fowlers, and fishermen are also mentioned, some of which were located near cities.

Inscriptions and Village Life:

- Early Tamil–Brahmi inscriptions provide insights into village life in Tamilakam.

- A 2nd-century BCE inscription at Varichiyur records the gift of 100 kalams of rice.

- A 1st-century BCE inscription at Alagarmalai refers to a koluvanikan (trader in ploughshares).

- A 2nd-century BCE inscription at Mudalaikulam is believed to refer to the construction of a tank by the assembly (ur) of Vempil village, possibly the earliest reference to a village assembly in the Indian subcontinent.

Plant Remains from Sanghol

Archaeological data on the agricultural economy of settlements in the subcontinent during the early historical period is limited compared to earlier times, with only a few exceptions providing insights.

A. K. Pokharia and K. S. Saraswat conducted a study at the site of Sanghol in Ludhiana district, Punjab, where they collected over 300 plant samples from 28 trenches dating to the 'Kushana' habitational levels (around 100–300 CE).

From their analysis, they identified carbonized remains of various crop plants, spices, fruits, and a dye-plant, including:

Cereal Crops

- Rice ( Oryza sativa )

- Two varieties of barley:

- Hordeum vulgare emend. Bowden

- Hordeum vulgare Bowden var. nudum

- Wheat ( Triticum )

- Jowar millet ( Sorghum bicolor Moench )

Pulses

Chickpeas ( Cicer arietinum ), Field Peas ( Pisum arvense ), Lentils ( Lens culinaris Medik ), Grass Peas ( Lathyrus sativus ), Green Grams ( Vigna radiata Wilczek ), Black Grams ( Vigna mungo Hepper ), Cowpeas ( Vigna unguiculata Walp. ), Horse Grams ( Dolichos biflorus ).

Oil Seeds

Field Brassica ( Brassica juncea Czern and Coss. ), Sesame ( Sesamum indicum, til ).

Fibre Crops

Cotton ( Gossypium arboreum G. herbaceum ).

Spices and Condiments

Fenugreek ( Trigonella foenum-graecum ), Coriander ( Coriandrum sativum ), Cumin ( Cuminum cyminum ), Black Pepper ( Piper nigrum ).

Fruits

Dates ( Phoenix sp. ), Indian Gooseberries ( Emblica officinalis ), Jujubes ( Zizyphus nummularia ), Custard Apples ( Annona squamosa ), Walnuts ( Juglans regia ), Almonds ( Prunus amygdalus Batsch ), Grapes/Raisins ( Vitis vinifera ), Java Plums ( Syzygium cumini ), Phalsa Berries ( Grewia ), Soapnuts ( Sapindus cf. emarginatus Vahl./trifoliatus/laurifolius Vahl. ), Chebulic Myrobalans ( Terminalia chebula Retz. ).

Dye Plant

Cities of the North-West

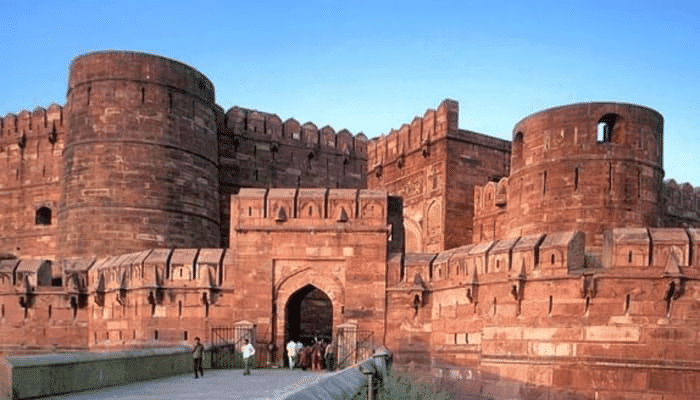

- Pushkalavati, located at the site of Charsada, was a significant city during this period. It covered about 4 square miles and was known as Peucelaotis or Proclais in Graeco-Roman accounts. Historical records mention it as a place where Philip had to station a Macedonian garrison due to its revolt against Alexander. The city was important during the Indo-Greek period but declined somewhat in the Kushana period as Purushapura (modern Peshawar) rose in prominence. However, Pushkalavati remained a major trade center.

- Early Settlement : The occupation at the Bala Hisar mound in Charsada dates back to the 6th century BCE. By the 4th century BCE, the settlement had grown and was protected by mud fortifications and a ditch.

- Shaikhan Mound Excavations : Aerial photography revealed a city with a rectangular plan, parallel streets, and blocks of houses, dominated by a large circular structure, likely a Buddhist stupa. Excavations indicated occupation from the mid-2nd century BCE to the mid-3rd century CE.

- House Structures : Earlier houses were made of stone diaper masonry, while Kushana phase houses were built of mud-brick. Various house types were identified, including one with a central fireplace and another with a courtyard and rooms on three sides.

- Taxila and Sirkap : In Taxila, a new city called Sirkap was laid out in the early 2nd century BCE, marked by grid planning with streets and structures in a chessboard pattern. Excavations revealed seven occupational levels, ranging from the pre-Indo-Greek to the Shaka-Parthian phase. The city expanded in the 1st century BCE, with a stone fortification wall and a massive northern gateway.

Stone Masonry from the 1st Century BCE to the Medieval Era

The city of Sirkap was divided by a main street, which separated it into two parts. The street was lined with various structures, including houses, small stupas, and at least two identified shrines.

Houses

- The houses in Sirkap were constructed using rubble masonry and plastered with mud.

- Most houses were spacious, averaging 1,395 square meters, and were organized around one or more courtyards.

- One particularly large house featured four courtyards and over thirty rooms.

- The presence of jewelry and metal artifacts suggests that wealthy individuals inhabited this part of the city.

- Rooms facing the main street may have functioned as shops.

- In the southeastern area of the excavated site, Marshall identified a complex that he believed to be a palace.

Establishment of Taxila

- Towards the end of the 1st century CE, the Kushanas founded a new city at Taxila, known as Sirsukh, located about a mile northeast of Sirkap.

- Excavations at Sirsukh have been limited, but a section of the stone rubble fortification wall has been discovered, featuring semi-circular bastions at regular intervals.

- Within the fortified area, two open courts with attached rooms have been identified, likely part of a large building.

Other Cities Mentioned in Texts

- Sagala (Sakala) : Identified with modern Sialkot, this city was the capital of the Indo-Greek king Menander and held significance as a trading hub.

- Purushapura : Tentatively identified with Peshawar, there is limited archaeological evidence for this settlement, apart from the excavation of the relic stupa at Shah-ji-ki-dheri, attributed to the reign of Kanishka.

- Patala : Mentioned by Greek historians as an important port in the Sindh delta, Patala has been tentatively identified with Bahmanabad, although this identification remains uncertain.

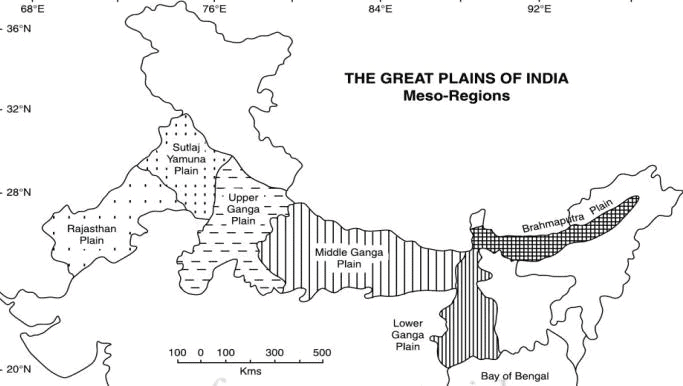

The Indo-Gangetic Divide and the Upper Ganga Valley

Remains from around 200 BCE to 300 CE have been discovered at various sites in the Indo-Gangetic divide and the upper Ganga valley.

Sunet (Ancient Sunetra) in the Ludhiana district of Punjab shows evidence of occupation from the late Harappan phase onward. Period IV at this site, dating to around 200 BCE to 300 CE, revealed a burnt-brick house featuring:

- Courtyard: A central courtyard.

- Rooms: Two rooms at the back, including a kitchen, bathroom, and grain storage room.

- Stairs: Indications of a two-storeyed structure.

- Drainage: Advanced drainage provisions.

- Servants' Quarters: Mud huts on three sides, possibly used as servants' quarters.

Sunet also yielded a hoard of 30,000 Yaudheya coin moulds, along with numerous seals and sealings.

- Sanghol, another site in Punjab, also contains remains from this period, including a stupa from the early centuries CE and 117 sculptures belonging to the Mathura school of art.

- Agroha in Hissar district (Haryana) exhibits early historical occupation with brick structures dating to the 3rd–4th centuries CE. At Karna-ka-Qila, Period I corresponds to the NBPW phase, while Period II reveals several structural phases from the early centuries CE.

Hastinapura (Meerut District, UP)

- Period IV at Hastinapura dates to around 2nd century BCE to late 3rd century CE.

- Pottery includes wheel-turned red ware with various forms like bowls, spouted basins, and miniature vases, featuring stamped and incised designs such as fish, leaves, and geometric patterns.

- The settlement shows planning with burnt brick houses and seven structural sub-phases.

- Artefacts include iron and copper objects, a stone rotary quern, carved ivory handles, and terracotta figurines, with notable pieces like a terracotta torso of the bodhisattva Maitreya.

- Coins from rulers of Mathura and the Yaudheyas, along with imitations of Kushana coins, were found.

Excavated Section of the Mound

Purana Qila, Delhi: Periods II and III

- Period II: 2nd–1st centuries BCE

- Period III: 1st–3rd centuries CE

- Both periods reflect urban prosperity with significant cultural activity.

Architectural Developments

- Early Houses: Made of quartzite rubble set in mud mortar.

- Later Houses: Constructed from mud-brick and burnt brick.

- House Floors: Generally made of rammed earth; some were paved with mud-bricks.

Artefact Richness

- Terracotta Items: Notably rich in quantity and quality compared to earlier levels.

- Included animal and human figurines,beads,skin rubbers,votive tank fragments, and crucibles.

- Terracotta plaques depicted various figures, including couples,yaksha-yakshi pairs,female figures, a lute player, and elephant riders.

Other Discoveries

- Bone points and a small piece of an ivory handle.

- Seals and sealings with names in Brahmi script (e.g., Patihaka, Svatiguta, Usasena,and Thiya).

- Copper coins from the Kushana and Yaudheya periods.

Additional Sites

- Mandoli and Bhorgarh: Occupational levels and artefacts from c. 200 BCE–300 CE were also found at these locations in Delhi.

Purana Qila: Walls of Different Periods

In a previous chapter, we discussed the NBPW Period IV at Atranjikhera, which is further divided into four sub-phases: IVA, IVB, IVC, and IVD. Here, we will focus on Period IVC (around 350–200 BCE) and IVD (around 200–50 BCE), during which the settlement expanded into a town.

Period IVC (c. 350–200 BCE)

- During this period, there was a notable increase in building activity and the use of burnt brick.

- Archaeological findings from this period include brick walls, floors, drains, barns, a granary, and terracotta ring wells.

- The fortifications of the site were likely constructed during Period IVC and underwent four stages of strengthening and renovation.

Period IVD (c. 200–50 BCE)

- This period saw the discovery of important structural remains, including an apsidal temple.

- The temple was associated with a broken plaque depicting Gaja-Lakshmi, the goddess Lakshmi flanked by elephants.

- The site during this period also experienced several instances of flooding.

Mathura: An Overview

- Mathura emerged as a significant centre for craft activities, particularly in textiles, and trade.

- It was also a religious hub associated with Buddhism, Jainism, and early Hinduism.

- As the southern capital of the Kushana empire, Mathura became an important political centre.

Period III (2nd–late 1st century BCE)

- This period in Mathura's sequence showed a marked increase in urban features.

- The ceramic assemblage was dominated by red ware, with some grey ware present.

- There was a gradual increase in the number of burnt brick structures.

- Terracottas and other craft items from this period displayed stylistic sophistication.

- The period also saw the presence of many inscribed coins, seals, and sealings.

Period IV (1st-3rd centuries CE)

- In this period, the fortification wall, which had fallen into disuse in the previous period, was strengthened, enlarged, and supplemented with an inner fortification.

- The red wares of this period included pots with painted and stamped designs, while the quantity of fine red polished ware was more limited, including items like sprinklers.

Sonkh: A Similar Trend

- Archaeological findings from Sonkh indicate a similar pattern of increasing urban complexity and sophistication during this period.

Terracotta Plaque

Excavations in Ayodhya (located in the Faizabad district of Uttar Pradesh) have uncovered structural remains and artifacts dating back to this period. During the late phase of the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW), there were houses constructed from burnt bricks and terracotta ring wells. Among the earliest Jaina images discovered so far is a grey terracotta figure of a Jaina saint, believed to date to the 4th or 3rd century BCE.

- In later layers, various items were found, including punch-marked coins, uninscribed and inscribed cast coins, copper coins with inscriptions, and numerous terracotta sealings. The presence of rouletted ware indicates trade connections with eastern India, where this type of pottery is found in large quantities. The report from the recent excavations in 2002–03 at Ayodhya lists several artifacts discovered dating to around the 2nd to 1st centuries BCE (Period II).

- These include various types of pottery such as black-slipped, red, and grey ware, as well as terracotta objects like human and animal figurines, bangle fragments, a ball, a wheel, and a broken sealing with the Brahmi letter "sa" partially legible. Other findings include a stone saddle quern and lid fragment, a glass bead, a bone hairpin, an engraver, and ivory dice. Additionally, a stone-and-brick structure was identified. Levels dating to the 1st to 3rd centuries CE (Period III) yielded red ware, terracotta figurines of humans and animals, bangle fragments, a terracotta votive tank, glass beads, and copper antimony rods. Stone and brick structures were discovered in this period and later, including a massive brick structure comprising 22 courses.

- At Sringaverapura (in the Allahabad district of Uttar Pradesh), the settlement reached its peak size in the 2nd century BCE. Excavations revealed an intricate brick tank complex from the late centuries BCE. B. Lal (1993) proposes that this tank, showcasing impressive engineering skills, was likely designed to provide drinking water for the growing settlement, as its eastern part was no longer in close proximity to the Ganga River. Water was redirected from the river into the tank through a channel. Additionally, a late Kushana period structural complex was found, consisting of two sections divided by a corridor. One of the rooms within this complex contained a small copper bowl with remnants of seeds and pulses.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|