Emerging Regional Configurations, c. 600–1200 CE - 1 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

Literary and Archaeological

Sheldon Pollock argues that there were two significant transformations in culture and power in pre-modern India. The first transformation occurred around the beginning of the Common Era when Sanskrit, originally a sacred language used in religious contexts, was 're-invented' as a language for literary and political expression. This shift eventually expanded Sanskrit's influence beyond the subcontinent. The second transformation took place in the early second millennium CE, when vernacular speech forms evolved into literary languages, challenging and eventually replacing Sanskrit's dominance.

Early Medieval Period Literature

- Early medieval Sanskrit literature is often seen as pedantic, ornate, and artificial.

- Types of Literature: Includes philosophical commentaries, religious texts, monologue plays (bhanas), hymn compositions (stotras), story literature, and anthologies of poetry.

- Popular Themes: Historical and epic-Puranic themes were common in kavya (poetry).

- Technical Literature: Works on metre, grammar, lexicography, poetics, music, architecture, medicine, and mathematics.

Royal Biographies and Historical Poetry

- Growth of Regional Polities: Accompanied by the composition of royal biographies by court poets.

- Notable Works: Banabhatta’s Harshacharita, Sandhyakaranandin’s Ramacharita, Padmagupta’s Navasahasankacharita, Bilhana’s Vikramankadevacharita, Hemachandra’s Kumarapalacharita, Chand Bardai’s Prithvirajaraso, Kalhana’s Rajatarangini.

- Historical Chronicles: Kalhana’s Rajatarangini is a notable historical chronicle of Kashmir's rulers.

Puranas and Upapuranas

- Theistic Elements: Early medieval Puranas reflect the growing popularity of theistic elements within Hindu cults.

- Notable Puranas: Bhagavata Purana, Brahmavaivarta Purana, Kalika Purana.

- Additions to Older Puranas: Sections on tirthas, vratas, penances, gifts, and the dharma of women were added during this period.

- Upapuranas: Composed in eastern India, these texts provide valuable information on popular beliefs, customs, and festivals, reflecting the dialogue between Brahmanical and non-Brahmanical ideas.

Vyavahara in the Early Medieval Period

- A. D. Mathur (2007) suggests that during the early medieval period, Hindu law (vyavahara) began to emerge independently from the dharma.

- This period saw the formalization of law and legal procedures, with an increasing tendency to empower the state to regulate and arbitrate social matters, including marriage issues.

Dharmashastra Compilations and Commentaries

- Numerous influential Dharmashastra compilations, digests, and commentaries were produced during this time.

- The Chaturvimshatimata compilation brought together the teachings of 24 law-givers.

- Jimutavahana authored the Vyavaharamatrika on procedural law and the Dayabhaga on inheritance, which became highly influential in Bengal.

- Major commentaries on the Manu Smriti by Medatithi, Govindaraja, and Kulluka, and commentaries on the Yajnavalkya Smriti by Vijnaneshvara and Apararka were also significant.

- Vijnaneshvara’s Mitakshara commentary became an authoritative text on various aspects of Hindu law.

- Other important works include Lakshmidhara’s Kritya Kalpataru and Devanabhatta’s Smritichandrika.

Literary and Historical Sources

- Most Prakrit works from this period are Jaina texts in the Maharashtri dialect, characterized by artificiality and ornamentation.

- Apabhramsha represents the final stage of the Prakrit languages, leading to the emergence of modern north Indian languages.

- Apabhramsha works include texts on Jaina doctrines, epic poems, short stories, and dohas (couplets).

- Tamil texts from this period include the devotional songs of the Alvars and Nayanmars, hagiographies of saints, and royal biographies such as the Nandikkalambakam.

- Kannada works, often associated with Jainism, were also produced under the patronage of the Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas, and Chalukyas.

- Literary sources provide both direct and indirect historical information. For example, the anonymous Lekhapaddhati offers models of legal documents, while the Krishi-Parashara deals with agriculture.

- Jain folk tales and mathematical texts like the Ganitasarasangraha and Lilavati offer incidental information about trade, prices, weights, measures, wages, and coins.

Chinese and Arab Accounts

- Xuanzang (c. 600–64 CE) and Yijing (635–713 CE), Chinese monks who visited India, provide valuable information about early medieval India.

- Yijing’s works detail Buddhist doctrines and the biographies of Chinese monks who traveled to India in the 7th century.

- Arab accounts from the 9th to 10th centuries by travelers and geographers like Sulaiman, Al-Masudi, Abu Zaid, Al-Biduri, and Ibn Haukal are important for understanding trade in early medieval India.

- Later Arab writers such as Al-Biruni, Al-Idrisi, Muhammad Ufi, and Ibn Batuta also contributed valuable information about India.

The Far South

Viragals in Tamil Nadu

- Concentrated near the southern border of Karnataka.

- Predominantly from the 5th/6th to 12th centuries CE.

- Early inscriptions in Tamil language and Vatteluttu script; later ones in Tamil language and Tamil script.

- Most records death in cattle raids; some mention battles, robberies, and wild animal attacks.

- Hero stones are simpler, featuring a single relief panel of the hero with weapons, often in a dynamic pose.

Political History

- Dominated by the Pallavas, Pandyas, Cheras, and Cholas.

- Pallavas:

- Associated with Tondaimandalam.

- Early kings like Shivaskandavarman (4th century CE).

- Simhavishnu:

- Crucial for Pallava rise in the late 6th century.

- Conquered land up to the Kaveri River.

- Conflicted with the Pandyas and the ruler of Sri Lanka.

- Mahendravarman I (590–630):

- Patron of the arts, poet, and musician.

- Initiated conflict with the Western Chalukyas.

- Narasimhavarman I Mahamalla (630–68):

- Achieved victories over the Chalukyas.

- Invasion of the Chalukya kingdom and capture of Badami.

- Claimed victories over the Cholas, Cheras, and Kalabhras.

- Patron of architecture; built the port of Mamallapuram and the five ratha temples.

Copper Coin, Pallava Dynasty

Gold Coin of Chola King Kulottunga I

- The conflict between the Pallavas and the Chalukyas persisted over the years, with periods of peace in between. The Pallavas also faced challenges from the Pandyas to the south and the Rashtrakutas to the north. In the early 9th century, Rashtrakuta Govinda III invaded Kanchi during the reign of Pallava Dantivarman.

- Dantivarman’s son, Nandivarman III, successfully defeated the Pandyas. The last notable imperial Pallava king was Aparajita, who, with the help of allies like the Western Gangas and Cholas, defeated the Pandyas at Shripurambiyam. However, the Pallavas were eventually overthrown around 893 by Chola king Aditya I, leading to Chola control over Tondaimandalam.

- The early historical period records kings of the Pandya dynasty, but it’s unclear how they relate to the early medieval Pandyas. The early medieval line began with Kadungon (560–90) and his son Maravarman Avanishulamani (590–620), who is credited with ending Kalabhra rule and reviving Pandya power.

- The Pandyas engaged in wars with the Pallavas and other powers, with Rajasimha I (735–65) earning the title Pallava-bhanjana for his victories over the Pallavas. The empire expanded under Rajasimha I and his successors Jatila Parantaka Nedunjadaiyan (756–815) and Shrimara Shrivallabha (815–862), but the Pandyas were eventually subdued by the Cholas in the 10th century.

- Along the Kerala coast, the Chera Perumals maintained their influence despite claims of military successes by Pallava, Pandya, Chalukya, and Rashtrakuta rulers. However, details about Chera history are scarce. One of the last known kings, Cheraman Perumal, is surrounded by legends, with varying accounts of his religious affiliations. It is believed he renounced worldly life, possibly dividing his kingdom among relatives or vassals, with his reign concluding in the early 9th century.

- The Chola kings are known from early historical South India, but their history after the Sangam period and their connection to early medieval Cholas are unclear. The early medieval Chola dynasty of Tanjore was founded by Vijayalaya, who established his authority around Uraiyur, captured Tanjore from the Muttaraiyar chieftains, and expanded his kingdom along the lower Kaveri River, accepting Pallava overlordship.

Expansion of the Chola Kingdom under Aditya I and Parantaka I

Aditya I (871–907) Achievements and Military Campaigns

- Defeated the Pandyas in collaboration with the Pallavas at Shripurambiyam, gaining territories in the Tanjore area.

- Overthrew his Pallava overlord, Aparajita, in 893, gaining control over Tondaimandalam.

- Conquered Kongudesha (present-day Coimbatore and Salem districts) from the Pandyas, possibly with assistance from the Cheras.

- Claimed to have captured Talakad, the capital of the Western Gangas.

- Strengthened ties with the Pallavas through a matrimonial alliance by marrying a Pallava princess.

Parantaka I (907–953) Victories and Challenges

- Conquered Madurai with the help of allies like the Western Gangas, the Kodumbalur chiefs, and the ruler of Kerala.

- Took on titles such as Madurantaka (destroyer of Madura) and Maduraikonda (capturer of Madurai).

- Achieved victory against the Pandyas and the king of Sri Lanka at the battle of Vellur, leading to the Chola takeover of Pandya territories.

Encounter with the Rashtrakutas

- Faced a significant defeat against the Rashtrakutas in 949 at the battle of Takkolam.

- The Rashtrakutas overran Tondaimandalam, with Krishna III claiming the title of ‘Conqueror of Kachchi (Kanchi) and Tanjai (Tanjore)’.

Recovery and Expansion

- The Chola power gradually restored during the reigns of later kings, such as Sundara Chola Parantaka II (957–973), who defeated a combined Pandya–Sri Lankan army and invaded the island kingdom.

- By the time of Uttama Chola (973), most of Tondaimandalam had been recovered from the Rashtrakutas.

Gold Coins of Rajendra Chola

Rajaraja Chola

Under the rule of Arumolivarman, who took the title of Rajaraja upon becoming king, the Chola Empire reached its zenith. From Rajaraja’s reign (985–1014) until the 13th century, the Cholas were the dominant political force in South India. Rajaraja Chola expanded the empire through military conquests, breaking the alliance between the Pandyas, Kerala, and Sri Lanka. He led a successful naval campaign that destroyed Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka, establishing a Chola province there. His victories extended to the Western Chalukyas and the Rashtrakutas, and towards the end of his reign, he conquered the Maldives.

Rajendra Chola

- Rajaraja's son, Rajendra I, continued the expansion with victories over Mahinda V of Sri Lanka and the rulers of the Pandyas, Kerala, and the Western Chalukyas. He founded a new capital at Gangaikondacholapuram and launched a successful naval expedition to the strategically important kingdom of Sri Vijaya in the Malay Peninsula. Subsequent Chola kings, including Kulottunga I (1070–1122), maintained military strength and engaged in trade with China and Sri Vijaya.

- Despite facing challenges from the Chalukyas and Hoysalas, Kulottunga I’s reign was relatively peaceful, and he earned the title Shungam-tavirtta for abolishing tolls. The Chola dynasty experienced a decline after this period, with later rulers like Vikrama Chola, Kulottunga II, Rajaraja II, and Kulottunga III, until its eventual end in the 13th century.

- Chola inscriptions often refer to the king with titles like ko (king), perumal, or peruman adigal (the great one) and grand titles like raja-rajadhiraja and ko-konmai-kondan (king of kings). The inscriptions depict the king as a handsome, great warrior, protector of varnashrama dharma, and a generous giver, particularly to Brahmanas, and a patron of the arts. Kings were often compared to gods, and Rajaraja, for instance, is referred to as Ulakalanda Perumal, which could signify both his land survey for revenue and the god Vishnu’s myth of measuring the universe with his three strides.

Origin Myths and Ancestry Claims of Early Medieval Dynasties

Early medieval dynasties in South India, like the early historical period, created new origin myths for themselves. These myths were based on epic and Puranic traditions, specifically the Suryavamsha (solar lineage) and Chandravamsha (lunar lineage).

- Some origin myths combined both Brahmana and Kshatriya ancestry, known as brahma-kshatra ancestry, with a focus on Kshatriya ancestry.

- Claims to Kshatriya status were reflected in royal titles and name suffixes, such as Rajaraja’s title of Kshatriya-shikhamani and names ending in ‘varman,’ which was prescribed for Kshatriyas in texts like the Manu Smriti.

- The Pandyas associated themselves with the lunar dynasty, while the Cholas claimed descent from the solar dynasty.

- The Pallavas asserted their Brahmana status from the Bharadvaja gotra and traced their lineage back to the god Brahma, listing several prominent figures, including Angiras, Brihaspati, Shamyu, Bharadvaja, Drona, Ashvatthama, and the eponymous Pallava.

Religious and Political Significance in the Tanjavur Temple

Shiva as Tripurantaka

- Tanjavur, or Tanjai, served as the political and ceremonial hub of the imperial Cholas. Situated at the southwestern tip of the fertile Kaveri delta, Tanjavur benefited from a rich agrarian resource base.

- The Brihadishvara temple, dedicated to Shiva and built during Rajaraja’s reign, stood as the physical and symbolic centre of Tanjavur. This imperial temple was closely associated with the ruling dynasty, evident in its alternate name, the Rajarajeshvara temple.

- The temple’s sculptures and paintings further reflected its connection to the ruling dynasty.

- The walls of the Brihadishvara temple feature various forms of Shiva, including Nataraja, Harihara, Lingodbhava, Ardhanarishvara, and Bhairava, as well as other deities like Gaja-Lakshmi, Sarasvati, Durga, Vishnu, and Ganesha.

- Notably, the Tripurantaka form of Shiva stands out, depicting the Puranic story of Shiva destroying the three cities of demons with a single arrow. This form became prominent during the Chola period, seen in multiple niches, sculpted panels, and fresco paintings within the temple.

- A bronze image, originally from the temple, also likely depicts Shiva Tripurantaka, showcasing the god in an archer’s pose, though the bow and arrow are not depicted.

Iconographic Programme in Tanjavur Temple

- R. Champakalakshmi highlights the significance of the Tripurantaka form of Shiva in the Tanjavur temple as part of a broader iconographic plan.

- The temple symbolized Rajaraja’s power, and the Tripurantaka form likely held special political significance, aligning with the king’s image as a great conqueror.

Tripurantaka in Shaiva Bhakti

- The Tripurantaka story is a key episode in the Shaiva bhakti work called the Tevaram. In this story:

- Brahma is depicted as Shiva’s charioteer, Agni as his arrow, the Vedas as the wheels of his chariot, and the Mandara mountain as his bow.

- Vishnu, in the form of Mayamoha, attempts to deceive the demons, who remain devoted to Shiva.

- After destroying their three cities, Shiva makes two of the demons his doorkeepers and the third his drummer.

Subordination of Other Gods to Shiva

- The Tripurantaka story emphasizes the subordination of other gods to Shiva, aligning with Rajaraja’s aim to elevate the Shaiva cult in his kingdom.

- This form of Shiva reflected Rajaraja's political and religious objectives, reinforcing Shiva's supremacy.

Mural Depicting Rajaraja Chola

- A mural in the south wall of chamber 5 depicts Rajaraja Chola as a devoted follower of Shiva in the Dakshinamurti form, where Shiva imparts profound knowledge to sages.

Chera Inscriptions and Matrilineal Succession

- Chera inscriptions lack prashasti and genealogy, possibly due to a matrilineal system of succession, although this is debated.

- Later literary sources, like the Periyapuranam and Keralolpatti, highlight the role of Brahmanas and temples in the dynasty’s origins.

Pandya Inscriptions and Indigenous Traditions

- Pandya inscriptions blend northern Brahmanical and indigenous Tamil traditions.

- Kings claim their twin fish emblem was carved on the Himalayas or Mount Meru, and they were anointed and taught Tamil by the sage Agastya.

- The copper plate grants feature Sanskrit and Tamil portions, with the Tamil section often more detailed.

Language and Inscriptions

- In Chola and Pallava inscriptions, the royal prashasti is usually in Sanskrit, with the rest in Tamil.

Legitimation of Power by South Indian Kings

- Connection to Epic-Puranic Tradition: South Indian kings legitimized their power by linking themselves to the ancient epic and Puranic traditions.

- Performance of Sacrifices: Kings also legitimized their authority through the performance of significant sacrifices such as the ashvamedha (horse sacrifice) and rajasuya (royal consecration).

- Mention of Rituals: Inscriptions from this period mention various rituals like the hiranyagarbha (golden womb) and tulapurusha (weighing a person against gold).

- Land Gifting to Brahmanas: The practice of gifting land to Brahmanas (priests) was a crucial activity linked to the legitimation of royal power.

- Gifts to Temples: Making various kinds of gifts to temples was another important activity associated with legitimizing royal authority.

North India: The Pushyabhutis and Harshavardhana

Sources of Information

- The main sources of information about the Pushyabhuti dynasty are the Harshacharita, a biography written by Banabhatta, and the account of the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang.

Origins of the Pushyabhuti Dynasty

- The Pushyabhutis were originally based around Sthanishvara, which is now known as Thanesar in the Ambala district of Punjab.

- Little is known about the first three kings of the dynasty.

Prabhakaravardhana and the Maukhari Alliance

- The fourth king, Prabhakaravardhana, was a great general with many military victories.

- He forged an important alliance by marrying his daughter Rajyashri to Grahavarman, the Maukhari ruler of Kanyakubja (Kanauj).

Rajyavardhana's Struggles

- Prabhakaravardhana was succeeded by his son Rajyavardhana around 605 CE.

- After Rajyavardhana's death, his brother Harshavardhana became king.

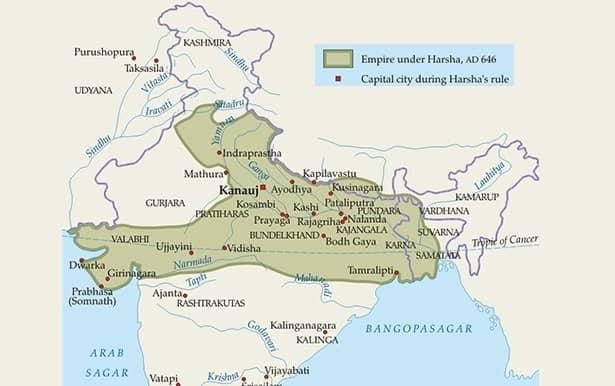

Harsha's Reign

- Harshavardhana, also known as Harsha, expanded his empire through military victories, including defeats of rulers in Orissa, Sindh, Valabhi, and Kashmir.

- His empire included regions like Thanesar, Kanauj, Ahichchhatra, Shravasti, and Prayaga.

- The Narmada River marked the southern boundary of his empire, while he exerted influence in the east, west, and parts of Magadha and Orissa.

Overlordship and Tribute System

- Rulers in the east, such as Bhaskaravarman of Kamarupa, and in the west, like the king of Valabhi, accepted Harsha's overlordship.

- Forest chiefs from the Vindhya region also recognized his authority, likely involving tribute payments and military alliances.

Harsha Era and Inscriptions

- Subordinate rulers used the Harsha era of 606 CE in their inscriptions, indicating their allegiance to him.

Diplomatic Relations

- Harshavardhana's reign also involved diplomatic relations, including embassies with China.

- Xuanzang provides a detailed and vivid account of Kanauj during the reign of King Harsha. He describes the city as beautiful, grand, and prosperous, reflecting the wealth and importance of Harsha’s empire. Xuanzang notes that Harsha was a diligent ruler who divided his day into three parts: one part for administrative duties and the other two for religious activities. This shows Harsha’s commitment to both governance and spirituality.

- Administrative Practices Xuanzang mentions that Harsha frequently toured his kingdom to inspect and ensure the well-being of his subjects. Periodic assemblies with subordinate kings reinforced the political hierarchy and unity within the empire.

- Land Grants Harsha was known for making religious land grants, which were a form of payment for ministers and officials. This practice highlights the intertwining of religion and governance in Harsha’s rule. Xuanzang’s account provides valuable insights into the administrative and religious practices of Harsha’s empire, showcasing the king’s dedication to his duties and the prosperity of his kingdom.

Xuanzang: Life and Journey

- Xuanzang was the youngest of four brothers. His father, Hui, had declined a high government position to focus on studying and writing. When Xuanzang was under 12, one of his brothers took him to a Buddhist monastery, where he soon became a novice monk. At that time, China was facing political instability, famine, and disturbances in cities. Xuanzang moved from one monastery to another during this period of unrest and was eventually ordained as a monk in Ch’eng-tu.

- After spending more years in China traveling and studying, Xuanzang decided to journey to India. He began his trip in 629 CE and spent around 13 years exploring the Indian subcontinent, from about 630 to 644 CE. During his travels, he gathered numerous manuscripts, though some were lost when the Indus River flooded during his return journey. Upon reaching China, he documented his experiences in a book called Da Tang xi yu ji, previously written as Si-yu-ki.

- Despite being a monk, Xuanzang was observant of political matters, possibly due to his family history. His ancestors were known for their scholarship and had held significant administrative roles. However, there were instances where Xuanzang idealized the situation in India. For example, he mentioned harsh punishments for those who disobeyed filial piety, reflecting the Chinese value of this virtue. Scholar D. Devahuti suggests that Xuanzang was not as biased as some believe.

- He sometimes praised non-Buddhist rulers and criticized Buddhist ones. Devahuti also notes that Xuanzang wrote about his Indian travels after returning to China, far from Harsha’s court, and had no reason to flatter the king. Tansen Sen highlights Xuanzang’s work as a unique resource for understanding ancient cross-cultural views. It was intended for Chinese monks and the Tang emperor, offering insights into Buddhist practices, as well as details about India in the 7th century, including its landscape, climate, produce, cities, caste system, and customs.

- Xuanzang portrayed Harsha positively, depicting him as a virtuous and courageous ruler supportive of Buddhism. His meeting with the king led to improved diplomatic ties between Kanauj and the Tang court. Even after returning to China, Xuanzang continued to foster religious and diplomatic relations between China and India.

Harsha's administration

- Limited details are available about Harsha's administration, but there was broad continuity in official designations from the Gupta period.

- Forest guards known as vanapalas and an official called the sarva-palli-pati (chief of all villages) are mentioned in inscriptions from Harsha's time.

- Xuanzang, a Chinese traveler, noted that people were lightly taxed under Harsha, with the king taking one-sixth of the farmer's produce as his share.

- Inscriptions from this period mention various dues such as bhaga, bhoga, kara, and hiranya, which were known from earlier inscriptions.

- The army during Harsha's reign is described by Xuanzang as consisting of infantry, cavalry, chariots, and elephants.

- The Banskhera and Madhuban inscriptions refer to the king's camp of victory, which included boats, elephants, and horses.

Religious and cultural patronage

- Inscriptional evidence suggests that the early Pushyabhuti rulers were worshippers of Surya (the sun god). Rajyavardhana, one of Harsha's predecessors, was a devotee of the Buddha. Harsha himself was a devotee of Shiva but also showed favor towards Buddhism.

- Harsha convened a significant assembly at Kanauj, attended by Xuanzang and others who gave discourses on Mahayana Buddhism. Various sects, including Shramanas (Buddhist monks), Brahmanas (Brahmins), and adherents of different sects, were invited to this grand conclave, along with subordinate kings from regions like Assam and Valabhi.

- Harsha was a patron of learning and the arts and was believed to have various talents himself. He is credited with writing three dramas, a work on grammar, and at least two Sutra works.

- The three plays attributed to Harsha are the Ratnavali, Priyadarshika, and Nagananda. The Nagananda tells the story of the bodhisattva Jimutavahana, while the Ratnavali and Priyadarshika are romantic comedies.

- It is possible that Harsha himself composed the texts of the Banskhera and Madhuban inscriptions, showcasing his calligraphic skills and signature. Harsha was also known as an accomplished lute player.

- Writers such as Bana, Mayura, and Matanga Divakara were associated with Harsha's court, contributing to its cultural and literary richness.

Harsha's death and political aftermath

- Harsha's death in 648 CE was followed by a period of political confusion until the rise of Yashovarman around 715–745 CE.

- After Yashovarman, various lineages competed for control over Kanauj.

- A significant feature of this political period was the tripartite struggle between the Rashtrakutas, Palas, and Gurjara-Pratiharas for dominance in northern India.

Eastern India

- After Shashanka: After King Shashanka's death around 637 CE, Bengal experienced over a century of political turmoil. Various powers, including Yashovarman of Kanauj, Lalitaditya of Kashmir, and a Chinese army, invaded the region.

- Rise of Dharmapala: Eventually, Gopala, the founder of the Pala dynasty, was elected by the people to restore order. His successor, Dharmapala (770–810 CE), initially faced defeats but later expanded the empire significantly.

- Dharmapala’s Achievements: Dharmapala held a durbar (royal assembly) at Kanauj, asserting his dominance over northern India. His empire's core was in Bengal and Bihar, with Kanauj as a dependency. Rulers from Punjab, Rajputana, Malwa, and Berar acknowledged his sovereignty.

- Buddhist Monasteries: Tibetan tradition credits Dharmapala with establishing the Vikramashila monastery and the Odantapuri monastery, while he also founded the Somapuri monastery in Varendra.

- Devapala’s Expansion: Devapala (810–850 CE) further expanded the empire, claiming tribute from all of northern India and conducting military campaigns across vast regions. He was a significant patron of Buddhism.

- Decline and Revival: The Pala power declined in the late 9th century due to defeats by the Rashtrakutas and Pratiharas. However, there were periods of revival under Mahipala I in the late 10th century and brief recoveries in the 11th century before a final decline in the 12th century.

- During the reign of Devapala, the Palas held power over Assam, known then as Kamarupa or Pragjyotisha. However, around 800 CE, a local ruler named Harjaravarman in Kamarupa rebelled against the Pala authority and established his independence. This is indicated by his imperial titles and the absence of Pala references in the inscriptions of his successors.

- Harjaravarman's dynasty, called the Salamba dynasty, ruled from approximately 800 to 1000 CE, with their capital at Haruppeshvara, situated on the banks of the Lauhitya river, now part of the Brahmaputra. Traditionally, the western boundary of Kamarupa was marked by the Karatoya river.

- In Orissa, during the late 6th century, the Shailodbhavas established their dominance in Kongoda, corresponding to modern-day Puri and Ganjam districts. Initially under the control of Shashanka, they later asserted their independence. The decline of the Shailodbhavas in the 8th century coincided with the rise of the Gangas of Shvetaka, migrants from Karnataka who settled in the north Ganjam area.

- The Gangas of Kalinganagara, also migrants from Karnataka, arrived in Orissa by the end of the 5th century and established themselves in the Vamsadhara and Nagavali valleys, claiming overlordship over Kalinga through their military prowess. In north Orissa, the Bhauma-Karas exercised power from the 8th or 9th century into the 10th century.

- Between the 10th and mid-12th centuries, several new dynasties emerged in Orissa. In north and central Orissa, various lineages with the suffix 'bhanja' gained prominence, including the Bhanjas of Khinjali mandala, the Adi Bhanjas of Khijjinga-kotta, and the Bhanjas of Baudh.

- The Shulkis and Tungas ruled over the Dhenkanal area during this period, while the Nandodbhavas were established in Dhenkanal and adjoining Cuttack and Puri areas. The Somavamshis of Dakshina-Kosala expanded their territory in the 10th century, establishing a significant empire in northern and central Orissa.

- The Ganga kingdom began its rapid expansion in the 10th century, achieving the unification of north and south Orissa by the 12th century. King Anantavarman Chodaganga played a crucial role in this expansion by displacing Somavamshi rule in lower Orissa and extending Ganga influence into Bengal.

- The Ganga military expansion was likely supported by alliances with the Cholas, although conflicts, such as those initiated by Kulottunga I against Kalinga, also occurred. Anantavarman’s dynasty was further strengthened by Chola connections, as his mother and one of his queens were Chola princesses.

Major Dynasties of Northern, Central, and Eastern India

Origins of Lineages:

- Lineage names and genealogical accounts can provide insights into the origins of certain lineages.

- However, in some cases, such as with the Shailodbhavas, Kulikas, Shulkis, and Bhauma-Karas, these accounts suggest tribal origins.

- Other kings, like the Tungas, Somavamshis, and imperial Gangas, used gotra designations, indicating their claims to Brahmana status.

Migration of Lineages:

- There is evidence of the migration of lineages, with various Gangas lineages being immigrants from Karnataka.

- The Bhauma-Karas may have migrated from Assam, the Somavamshis from south Kosala (eastern Madhya Pradesh and western Odisha), and the Tungas from Rohitagiri (identified with Rohtasgarh in Bihar).

Some origin myths of the dynasties of Orissa

- In the Orissa region, royal origin myths became increasingly elaborate after the 7th century. While the details of these myths cannot be regarded as historical facts, they convey important information about the origins of lineages. These myths were part of various strategies used by ruling lineages to legitimize their power, and it is crucial to analyze them carefully to understand the traditions to which these dynasties connected themselves.

- The origin myth found in Shailodbhava inscriptions tells the story of a man named Pulindasena, who was renowned among the people of Kalinga. Despite his virtues, strength, and greatness, Pulindasena did not seek power for himself. Instead, he worshipped the god Svayambhu, asking for the creation of a capable ruler for the earth. The god granted this wish, and Pulindasena witnessed a man emerging from a rock. This man was Shailodbhava, who went on to establish a distinguished lineage bearing his name.

- Some Shailodbhava inscriptions also attribute the miraculous birth of Shailodbhava to Hara or Shambhu (another name for Shiva). The Pulindas, an ancient tribe mentioned in various texts, are linked to Pulindasena, highlighting the tribal origins of the Shailodbhava dynasty. The motif of emerging or being born from a rock may symbolize the rocky terrain where the dynasty was initially based. The significance of Shiva is connected to the fact that the Shailodbhavas were devotees of this god, as evidenced by the Shaiva bull motif on their seals and the frequent invocations of Shiva in their inscriptions. Additionally, Shailodbhava inscriptions praise the Mahendra mountain, referring to it as a kula-giri or “tutelary mountain”.

Rajput Clans

The term "Rajaputra" for specific clans or as a general term for various clans became common by the 12th century. The Agnikula myth, which tells of certain clans arising from the fire of a great sacrifice by sage Vasishtha on Mount Abu, is also a relatively recent idea. The ‘Agnikula Rajputs’ included clans like the Pratiharas, Chaulukyas, Paramaras, and Chahamanas. Medieval bardic traditions in Rajasthan listed 36 Rajput clans, but these lists varied, showing that claims to Rajput status were not fixed.

Emergence of Rajputs

- B. D. Chattopadhyaya noted that the rise of the Rajputs was part of a broader trend of lineage-based states in early medieval India.

- Factors contributing to the emergence of these clans included:

- Expansion of the agrarian economy

- New land distribution methods, including land distribution among royal relatives

- Inter-clan cooperation through political and matrimonial alliances

- Unprecedented construction of fortresses

Gurjara-Pratihara Dynasty

- The Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty emerged in north India after the Gupta empire's collapse.

- Founded by a Brahmana named Harichandra around Jodhpur in Rajputana.

- Other Gurjara families established small principalities south and east of Jodhpur.

- The name "Pratihara" means doorkeeper.

- Early Jodhpur and imperial Pratiharas believed their name came from the epic hero Lakshmana serving as a doorkeeper to his brother Rama.

- Debates on Antecedents

- Some historians suggest the Gurjaras were a foreign people entering India after the Huna invasions, but evidence is lacking.

- Others propose "Gurjara" refers to a land, not a people, although in ancient times, people often named their land.

- A few scholars view the Gurjaras and Pratiharas as different groups, while others see the Pratiharas as a clan of the Gurajara tribe.

- Modern Gujars in northwest and western Rajasthan, Gujarat, and Uttar Pradesh may be descendants of the Gurjaras.

Silver Gurjara-Pratihara Coin

- The Gurjara-Pratiharas rose to prominence in the 8th century, notably under King Nagabhata I, who successfully resisted Arab invasions. This royal lineage became the most powerful Pratihara family, surpassing the Jodhpur branch, and expanded its control over parts of Malwa, Rajputana, and Gujarat. Later kings, such as Nagabhata II, extended their influence into the Kanauj region, often clashing with other powers like the Palas and Rashtrakutas.

- Bhoja, the most renowned Gurjara-Pratihara king and grandson of Nagabhata II, ruled for over 46 years, facing initial defeats but eventually achieving significant victories. His reign was marked by military power and wealth, as noted by the Arab merchant Sulaiman. However, the dynasty faced setbacks in the 10th century, leading to its decline and eventual disintegration, with remnants around Kanauj. The Gurjara-Pratiharas were succeeded by powerful states like the Chahamanas, Chaulukyas, and Paramaras, who shared a mythic origin with the Pratiharas, suggesting kinship ties.

- The Chandella dynasty, one of the 36 Rajput clans, claimed descent from a mythical ancestor, Chandratreya, and was historically founded by Nannuka in the 9th century. Initially vassals of the Gurjara-Pratiharas, the Chandellas gradually expanded their kingdom under early and later kings, such as Harsha, who played a crucial role in restoring Mahipala, a Pratihara ruler. The Chandellas asserted their independence as the Pratiharas and Palas declined, with Dhanga becoming the first independent king and commissioning several temples in Khajuraho.

The Chandella Kingdom

- Location and Borders: The Chandella kingdom was located to the north of the Narmada River, bordered to the south by the Kalachuri kingdom of Chedi country, also known as Dahala-mandala.

- Chedi Capital and Early Kings: The capital of Chedi, Tripuri, is believed to be present-day Tewar, near Jabalpur. Kokkala I, the first known king of the Kalachuri dynasty, likely became king around 845 AD and faced conflicts with the Pratiharas and their vassals.

- Later Kings: Subsequent rulers included Shankaragana, Yuvaraja, and Lakshmanaraja.

- Poet Rajashekhara: Rajashekhara, a poet linked to the Gurjara-Pratihara court, also interacted with the Kalachuri court. His play, the Viddhashalabhanjika, was performed in Yuvaraja's court to celebrate a victory against the Rashtrakutas.

- Kalachuri Power Struggles: The Kalachuri power declined during Yuvaraja II's reign due to defeats by Chalukya Taila II and Munja, the Paramara king of Malwa. However, under Kokkala II, the Kalachuris regained strength, launching successful campaigns against the Chaulukyas, Chalukyas, and the kingdom of Gauda.

- Debased Gold Coin of Chandella King, Madanavarma: This coin represents the Chandella dynasty, showcasing their influence and power.

The Paramaras of Malwa

- Origin and Legend: The Paramara dynasty is believed to have originated in the Mount Abu area of Rajasthan. According to legend, the sage Vishvamitra stole Vasishtha’s wish-granting cow. To retrieve it, Vasishtha performed a sacrifice on Mount Abu, from which a hero named Paramara emerged, becoming the king.

- Early History: Early Paramara inscriptions do not mention this legend; instead, they describe the kings as being from the family of the Rashtrakutas. The capital of the main Paramara branch was Dhara, modern-day Dhar in Madhya Pradesh.

- Vassals and Rise to Power: The early Paramaras were vassals of the Rashtrakutas. Upendra, an early ruler, may have been appointed by Rashtrakuta king Govinda III after a successful military campaign in Malwa.

- Decline and Revival: The Paramaras faced a decline when they lost Malwa to the Pratiharas but revived in the mid-10th century under rulers like Vairasimha II and Siyaka II.

- Siyaka II’s Achievements: Siyaka II asserted independence from the Rashtrakutas, defeating their army at Kalighatta and pursuing them to their capital Manyakheta.

- Munja’s Expansion: Munja, Siyaka II’s successor, expanded the empire, achieving military successes against the Kalachuris and sacking Tripuri. He led numerous expeditions, further solidifying Paramara power.

Munja and Sindhuraja

- Munja, a leader from the Paramara dynasty, expanded his rule into Rajputana and defeated the Hunas. He captured Aghata, the capital of the Guhilas of Medapata, and took territories from the Chahamanas of Naddula, including Mount Abu and southern areas of Jodhpur. Munja also invaded the Chaulukya kingdom but was eventually defeated by Chalukya ruler Taila II.

- Munja was not only a skilled military leader but also a poet and a patron of art and literature. He is credited with constructing many tanks and temples. His successor, Sindhuraja, managed to recover some of the lost territories from the Chalukyas.

Chaulukya Family

- The Chaulukya family, distinct from the Chalukyas, had at least three branches. The oldest branch ruled from Mattamayura in central India, with early rulers like Simhavarman, Sadhanva, and Avanivarman.

- Another branch was founded by Mularaja I, who established his capital at Anahilapataka (Anahilavada). A third branch was started by Barappa in Lata, with its centre at Bhrigukachchha (Broach) in southern Gujarat.

- Mularaja I led military expeditions into Saurashtra, Kutch, and against the Abhiras. However, his power declined due to invasions by the Chahamanas and the Chaulukyas of Lata. After a defeat by the Paramaras, Mularaja sought refuge with Rashtrakuta king Dhavala. He eventually recovered his kingdom, but his successors continued to face conflicts with the Kalachuris and Paramaras.

Guhilas of Mewar

- In Mewar, southeast Rajasthan, two lines of the Guhilas ruled from Nagda –Ahada and Kishkindha in the 7th century, along with a small Guhila principality at Dhav-agarta. By the 10th century, major Guhila families included Nagda–Ahada, Chatsu, Unstra, Bagodia, Nadol, and Mangrol.

- Early inscriptions of the Guhilas of Nagda–Ahada describe them as belonging to the lineage of Guhila. A 10th-century inscription lists 20 kings, starting with Guhadatta and ending with Shaktikumara. Guhadatta is said to be a Brahmana from Anandapura, later identified with Vadnagar in northeast Gujarat.

- Later inscriptions suggest Bappa Rawal as the founder of the dynasty, blending Brahmana and Kshatriya elements in their origin stories. These accounts illustrate the Guhilas' transformation from a local to a sub-regional state in the 10th century and eventually to a regional state of Mewar by the 13th century.

The Tomaras and Delhi: Legends and Inscriptions

- The Tomara Rajputs have a unique and significant connection with the Delhi region, as evidenced by historical inscriptions and medieval legends. One notable artifact is the iron pillar located in Mehrauli, Delhi. This pillar, inscribed with the name of king Chandra, also features several shorter inscriptions, including one from the 11th century that appears to reference Anangapala Tomara as the founder of Delhi.

- Medieval legends further illuminate the Tomara association with Delhi. One such legend, recounted in the Prithvirajaraso , tells of a learned Brahmana who informed the Rajput king Bilan Deo or Anangapala Tomara that the iron pillar was immoveable because its base rested on the hood of Vasuki, the serpent king.

- The Brahmana prophesied that Anangapala's rule would last as long as the pillar stood. Intrigued, the king ordered the pillar to be dug out, only to find its base smeared with serpent blood. Realizing his mistake, he ordered the pillar to be re-installed, but it remained loose. According to the legend, this looseness gave rise to the name "Dhilli" or "Dhillika," from which "Dilli" and "Delhi" are derived.

- While this story is mythical, archaeological evidence supports the Tomara connection to the Delhi area. For instance, Anangpur, located in the Badarpur region and mentioned in earlier chapters as a significant paleolithic site, contains remnants of early medieval fortifications and structures.

- The village's name is linked to one of the Tomara kings named Anangapala, and a stone masonry dam near the village is believed to have been built by him. Anangapala II, another Tomara king, is credited with founding the citadel of Lal Kot in the Mehrauli area and possibly constructing the Anang Tal tank. Additionally, the reservoir known as Suraj Kund is attributed to the Tomara king Surajpala, highlighting the Tomaras' role in establishing some of the earliest waterworks in the Delhi region.

- The succession of rulers in the Delhi area is documented in various inscriptions. For instance, a 12th-century inscription from Bijholia in Rajasthan refers to the Chauhan king Vigraharaja as the conqueror of Dhillika (Delhi). The 13th-century Palam Baoli inscription, discovered in a stepwell in Palam village, records the construction of a stepwell by Uddhara, a resident of Dhilli.

- This inscription also mentions the land of Hariyanaka, which was initially held by the Tomaras, then by the Chauhans, and later by the Shakas. Here, the term "Shaka" refers to the Delhi Sultans, and the inscription lists the Shaka rulers from Muhammad of Ghor to Balban.

- A 13th-century inscription from Sonepat, known as the Delhi Museum stone inscription, documents the construction of a well in Suvarnaprastha village and states that Dhillika in the Hariyana country was ruled successively by the Tomaras, Chahamanas, and Shakas.

- A 14th-century inscription from Sarban village near Raisina road in New Delhi recounts the building of a well in Saravala village by two merchants, Khetala and Paitala. This inscription provides a historical account of Dhilli, listing the same sequence of rulers as previous inscriptions, with the term "Turushka" (Turks) used for the Delhi Sultans instead of "Shaka."

The Anangpur Dam

Suraj Kund Reservoir

- Of the many branch lines of the Chahamanas, the oldest ruled in Lata till the mid-8th century. Another branch was founded by Lakshmana at Naddula in south Marwar. A third, founded by Vasudeva, established itself in the early 7th century in Shakambhari-pradesha with its capital at Shakambhari, which has been identified with Sambhar near Jaipur.

- The Chahamanas of Shakambhari were originally subordinates of the Pratiharas, with whom they also had matrimonial ties. They assumed independence during the reign of king Simharaja.

Billon Coin of Chahama King, Prithviraja II

- The Tomara kingdom was adjacent to that of the Chahamanas. The Tomaras ruled the Hariyana country from their capital Dhillika (Delhi), initially acknowledging Pratihara paramountcy. In the 10th century, they were involved in conflict with the Chahamanas of Shakambhari.

- They continued to rule until the mid-12th century, when they were overthrown by the Chahamana king Vigraharaja IV. Prithviraja III, also known as Rai Pithora, was one of Vigraharaja’s nephews. Bardic accounts, including the biographical epic, Prithviraja Raso, describe his many battles.

- These included his victory over the Turkish invader, Muhammad of Ghor, in the first battle of Tarain (1191), and his subsequent defeat at the hands of the same adversary on the same battlefield in 1192.

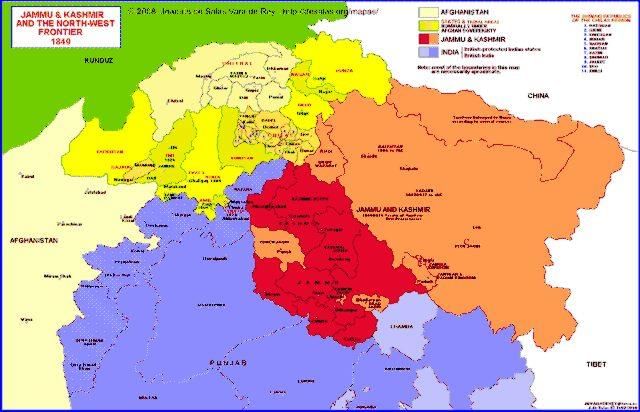

Kashmir and the North-West

Karkota Dynasty (8th Century CE):

- Founded by rulers like Lalitaditya.

- King Vajraditya faced Arab raids during his reign.

- Jayapida, a powerful king, led a three-year expedition against eastern countries, claiming victories over five chieftains of Gauda and the ruler of Kanyakubja.

Utpala Dynasty:

- Founded by Avantivarman after the Karkota dynasty ended in 855–56 CE.

- Avantivarman took measures to protect crops from flood waters of the Mahapadma (Wular) lake.

- Shankaravarman, another ruler, conducted military campaigns in Punjab and Gujarat.

- The later years of the Utpala dynasty were marked by political instability and frequent power shifts.

- Successors included kings like Yashaskara and Parvagupta.

Political Role of Military and Landed Chiefs:

- Early medieval Kashmir was influenced by bodies of soldiers such as the Tantrins (foot soldiers) and Ekangas (royal bodyguards).

- Landed chiefs known as the Damaras also played a significant role.

- There was a tradition of powerful queens in Kashmir, with Didda being the most notable, dominating politics in the late 10th century.

Turkish Shahiya Dynasty:

- Based in the Kabul valley and Gandhara area.

- In the late 9th century, Kallar, a Brahmana minister, overthrew the Shahiya king and established the Shahi dynasty.

- Kallar, identified with king Lalliya of the Rajatarangini, struggled to maintain control over the Kabul valley.

- After being defeated by Arab Sarrarid Yaqub ibn Layth in 870 CE, Kallar moved his capital to Udabhanda (modern Und village in Rawalpindi district).

Decline of the Shahi Dynasty:

- The Shahi dynasty eventually collapsed due to the Ghaznavid invasions.

Didda

Didda was a powerful queen in 12th century Kashmir, known for her long and eventful rule. She was one of three women rulers mentioned in the Rajatarangini, an ancient text by Kalhana. Didda ruled for nearly 50 years, including time as regent for her son and as queen in her own right. Kalhana describes her rise to power with the help of a loyal minister, Naravahana, and how she overcame her enemies despite being underestimated due to her physical weakness.

- Didda's Rise to Power : Didda, often referred to with respect as 'Didda', had a significant and lengthy political career in Kashmir, spanning nearly 50 years. Her journey included being the wife of King Kshemagupta, acting as regent for her young son Abhimanyu, and eventually ruling Kashmir independently after becoming queen in 980–81 CE.

- Support and Strategy : Kalhana, the author of the Rajatarangini, details how Didda was supported by a loyal minister, Naravahana, who helped establish her rule. Didda was initially underestimated due to her physical limitations, but she proved her strength by defeating her enemies and gaining control.

- Ruthless Ascendancy : Before becoming queen, Didda displayed ruthless ambition by eliminating her son and three grandsons. She also had a significant relationship with a courier and herdsman named Tunga, who became a trusted ally.

- Legacy and Contributions : Didda is credited with founding several towns and temples, including Diddapura and Kankanapura, and repairing many temples dedicated to various gods. Her reign is marked by significant contributions to the infrastructure and religious sites in Kashmir.

- Kalhana's Critique : Despite detailing Didda's achievements, Kalhana disapproved of her character, describing her as morally deficient and easily swayed. He viewed her actions as reflective of women's flaws, suggesting that even women from noble families tend to follow a downward path, much like rivers.

- Comparison with Other Rulers : Historians like Devika Rangachari compare Didda with women rulers from other regions, such as Rudramadevi in Andhra. Didda's ability to divert succession from her ruling family to her maternal lineage was a notable difference, indicating her unexpected strength and influence in establishing her rule.

Kalhana’s Rajatarangini

- Historical Relevance of Women: Kalhana, despite his biases, depicts both royal and non-royal women as significant figures in history. Women in Kashmir are shown as sovereign rulers and influential figures behind the throne, playing crucial roles in the establishment and downfall of dynasties.

- Political Influence: The Rajatarangini highlights the direct and indirect political impact of courtesans and women of ‘low’ birth within the harem. It indicates that, although Kashmir was under a patriarchal system, there were instances where male dominance over political power was challenged.

Arab Invasions in India

- Early Expeditions: The Arab incursions into western India began with a naval expedition to Thana (near present-day Mumbai) in 637 CE, followed by attempts to conquer Broach and Debal (a port in Sindh). These initial efforts did not lead to significant territorial gains.

- Campaigns in Afghanistan: The Arabs engaged in extended campaigns against the kingdoms of Zabul and Kabul in Afghanistan and launched several expeditions resulting in the conquest of Makran. Eventually, they established a foothold in Sindh under the leadership of Muhammad bin Qasim, following the orders of Hajjaj, the governor of Iraq.

- Conquest of Sindh: Muhammad bin Qasim’s campaigns led to the capture of key regions such as Debal, Nehrun (Hyderabad), and Siwistan (Sehwan), culminating in a decisive victory over King Dahar at the fort of Raor. Subsequent conquests included Alor, Brahmanabad, and Multan. These events are chronicled in the Chachnama, a 13th-century Persian translation of an Arabic history detailing bin Qasim’s conquests.

- Completion and Consolidation: The conquest of Sindh was finalized by Junaid, though Arab control over the region remained unstable for centuries. Junaid also attempted to expand into Malwa, but these efforts were resisted by local powers such as the Pratihara Nagabhata I and the Chalukya Pulakeshin II.

Turkish Invasions

- Ghazni and the Rise of Mahmud: In the 9th and 10th centuries, parts of Afghanistan were under the Samanid Empire. Alptagin, a Samanid slave who became governor of Balkh, founded an independent Turkish dynasty in Ghazni. His son-in-law, Subuktagin, established his rule in Ghazni in 977 CE, and his son Mahmud became notable for his raids into India.

- Conflicts and Campaigns: Mahmud of Ghazni launched 17 campaigns into the Indian subcontinent between 1000 and 1027 CE. His targets included the Shahiyas, Multan, Bhatinda, Narayanpur, Thaneshwar, Kanauj, Mathura, Kalinjar, and Somnath. Although these campaigns involved significant looting, they were not aimed at permanent conquest.

- Final Campaigns: Mahmud’s last Indian campaign was against the Jats, concluding a series of expeditions that aimed primarily at plunder rather than establishing long-term control over the conquered territories.

Royal Land Grants

Royal land grants are a crucial source for understanding the history of early medieval India and play a central role in debates about this period. During the time between approximately 600 and 1200 CE, there was a significant increase in the number of grants made by kings to Brahmanas. This phenomenon reveals both general patterns and regional specificities.

Donative Inscriptions

- Brahmadeyas, which refers to land gifted to Brahmanas, had a political dimension. These settlements were established by royal order, and the rights of the Brahmana recipients were declared and confirmed by royal decree.

- The feudalism hypothesis interprets brahmadeyas as both a cause and a symptom of political fragmentation. However, this interpretation is difficult to accept for various reasons.

- For instance, it raises questions about why kings would voluntarily erode their own power and whether this period was truly marked by political fragmentation. In fact, the early medieval period was characterized by an unprecedented proliferation of state polities at regional, sub-regional, and trans-regional levels, within a broader context of agrarian expansion.

- Far from being symptoms of disintegration or royal disempowerment, land grants to Brahmanas were integrative and legitimizing policies adopted by kings.

- For fledgling kingdoms, patronizing Brahmanas, a socially privileged group, did not represent a significant loss of revenue or control. In fact, kings granting land may not have been able to realize revenue from that land initially. For large, established kingdoms, making a few land grants did not deplete state resources significantly.

- The most grants, both to Brahmanas and religious establishments, were often made by powerful dynasties and kings. The increase in royal land grants indicates higher levels of control over productive resources by kings compared to earlier periods.

- Strategies of control, alliances, and collaboration with prestigious social groups were important aspects of politics during this time. The wealth and power of Brahmanas and institutions such as temples did not increase at the expense of royal power.

- Brahmanization of Royal Courts: Inscriptions from early medieval dynasties, apart from the Delhi Sultans, testify to the Brahmanization of royal courts across the subcontinent. Brahmanas emerged as ideologues and legitimizers of political power by crafting royal genealogies and performing prestigious sacrifices and rituals. Many royal genealogies linked lineages with the epic-Puranic tradition, assigning kings a respectable varna status.

- Origin Myths and Kingship: Origin myths enshrined in later literary sources of Kerala reflected the close relationship between kings, Brahmanas, and temples. For instance, these myths assigned an important place to Brahmanas and temples in their explanation of the origins of kingship.

- Political Role of Brahmanas: The direct political role of Brahmanas during the Chera period is evident in their inclusion in the Nalu Tali (the king’s council) at Mahodayapura, where Brahmanas from leading Brahmana settlements participated.

Brahmana Beneficiaries

During the early medieval period, there was a notable increase in the control and ownership of land by Brahmanas. While land grants to Brahmanas existed in earlier centuries, they became more common and widespread during this time. In earlier periods, land grants to Brahmanas were sometimes made by private individuals, at the request of the Brahmanas themselves, or by kings at the request of others. However, as time went on, these complexities became less visible in inscriptions.

- Despite this, there are still hints that other individuals may have influenced grants that appeared to be made solely by kings. For instance, a 13th-century inscription from Calcutta shows that a Brahmana named Halayudha received land from the king, but some of the plots had been purchased by Halayudha himself. This suggests that the king was ratifying these purchases rather than initiating the grant.

- In Orissa, some grants from the Bhauma-Kara and Ganga dynasties mention feudatories or their family members as the ones who requested the grant, supporting the idea that land grant charters often hid the true identity of those involved in the transaction. Common sense might imply that Brahmanas receiving land grants were linked to the royal court. Some inscriptions from Bengal describe donees as shantivarikas or shantyagarikas, indicating their role in performing religious rites for the king.

- In Orissa, Brahmanas were sometimes connected to the royal court as priests, astrologers, or administrators. However, most inscriptions do not show a court connection for the Brahmana donees.

- Inscriptions that mention Brahmana recipients of royal grants provide details about their ancestry, gotra, pravara, charana, shakha, and native place. Gotrarefers to the exogamous clan system of the Brahmanas, which is divided into ganas, each with its own pravaraconsisting of names of supposed ancestral rishis.

- Charanarefers to a school of Vedic learning, and shakhato a particular recension of a Veda. Inscriptions often use charana and shakha interchangeably, highlighting the Vedic learning of Brahmana donees by mentioning their titles such as acharya, upadhyaya, and pandita.

Migration Patterns

Early Migrations

- Earliest Migrations (c. 800 BCE): The initial migrations of Brahmanas, possibly starting around 800 BCE, are not well-documented and are surrounded by mythological narratives.

- Eastward Movement: This is reflected in the early Brahmanical literature's gradual acknowledgment of the eastern regions and the eastward extension of the term Aryavarta.

- Southward Movement: Early legends associated with figures like Agastya and Parusharama indicate a southward migration, with another phase associated with the Sangam age of South India.

Later Migrations

- 16th Century Keralolpatti: This document reflects a tradition of 32 original Brahmana settlements in Kerala, likely representing early medieval developments.

- Kulaji Texts of Bengal: These late medieval texts trace the ancestry of the Kulin Brahmanas to five Brahmanas from Kanyakubja, suggesting that the prestige of Brahmanas in early medieval India was based on Vedic learning and that learned Brahmanas were migrating from the Madhya-desha (middle Ganga valley) into eastern regions.

Influx of Brahmana Immigrants (5th Century Onwards)

- From the 5th century onwards, land grant inscriptions document the migration of Brahmana immigrants from the heartland of Madhya-desha into areas such as Maharashtra, Bengal, Madhya Pradesh, and Orissa.

- Some migrants originated from renowned centres of Brahmanical learning, including Takari, Shravasti, Kolancha, and Hastipada.

Intensification and Regional Differentiation (8th Century Onwards)

- The phenomenon of Brahmana migration intensified in the 8th century, leading to a broader division of groups into the Pancha-Gaudas (northern group) and the Pancha-Dravidas (southern groups).

- Pancha-Gaudas: This group included the Sarasvata, Gauda, Kanyakubja, Maithila, and Utkala Brahmanas.

- Pancha-Dravidas: Groups in this category included the Gurjjaras, Maharashtriyas, Karnatakas, Trailingas, and Dravidas.

Reasons for Brahmana Migrations

- The Brahmanas, traditionally known for their role in officiating sacrifices, began to migrate due to various factors. While political instability and land pressure were suggested reasons, these do not fully explain the migrations.

- Instead, the migrations were likely driven by the search for better livelihoods in specific historical contexts.

Decline of Sacrifice-Oriented Practices

- The earlier migrations eastward and southward may have been linked to the decline of sacrifice-oriented religious practices in North India during the early historical period.

- Brahmanas who relied on officiating at sacrifices for their income may have been compelled to leave their homes in search of more secure and lucrative occupations.

Early Medieval Migrations and New Opportunities

- The migrations during the early medieval period coincided with the rise of new kingdoms across the subcontinent.

- These emerging political elites required legitimation and administrative support, creating new opportunities for learned and literate Brahmanas.

Shift in Religious Practices

- By this time, popular religious practices had shifted towards theistic devotion, becoming less connected to the Vedas or shrauta rituals.

- Despite this shift, Brahmanas were still prominently featured in inscriptions as Vedic scholars, highlighting the disparity between the Sanskritic-Vedic tradition and the lives of ordinary people.

- This gap made the Vedic tradition a useful legitimizing tool for elite groups seeking to distinguish themselves from the masses.

Brahmanas with Non-Sanskritic Names

- Some inscriptions mention Brahmanas with unusual non-Sanskritic names, suggesting the possibility of Brahmanized tribal priests.

- For example, Eastern Chalukya inscriptions refer to Boya Brahmanas, who were originally priests of the Boya tribe and later Brahmanized.

- Inscriptions also occasionally mention Brahmanas with unheard-of gotras or mismatched gotras and pravaras, indicating groups that may have invented a Brahmana identity to improve their social and economic standing.

|

109 videos|652 docs|168 tests

|