Emerging Regional Configurations, c. 600–1200 CE - 2 | History for UPSC CSE PDF Download

The Nature of Brahmadeya Settlements

When examining brahmadeya settlements, it's challenging to separate the factual details from the theoretical perspectives, which often contradict each other in important ways. Additionally, while there are common features and trends applicable to most of the subcontinent, brahmadeyas in different regions, subregions, and time periods had their own unique characteristics.

- Formation and Characteristics: Not all Brahmana settlements resulted from royal land grants, and these villages likely constituted only a small fraction of settlements in many areas. From the state's perspective, creating brahmadeyas often meant relinquishing potential sources of revenue. Land grant inscriptions sometimes mentioned the transfer of rights over treasure troves, forests, and heirless property, which the king theoretically had rights over.

- State Prerogatives: The transfer of these rights to the donees would impact the state's prerogatives. Inscriptions also indicate that brahmadeyas were to be free from interference by the state, its officers, or soldiers. In the Chola Empire, some important brahmadeyas had a status called taniyur within the nadu (locality), making them independent of nadu jurisdiction.

- Autonomy and Relationship with the King: This suggests that brahmadeyas were, for practical purposes, autonomous entities in the rural landscape, where Brahmana donees had the freedom to manage affairs without state intervention. However, this independence was balanced by a close relationship with the king.

- Extension of Cultivation: In some instances, land grants involved establishing Brahmana settlements beyond existing agricultural boundaries, leading to an expansion of cultivation areas. However, most grants were made in already settled and cultivated areas, as evidenced by descriptions of gifted villages and details such as annual income and habitat land (vastu-bhumi) mentioned in post-12th century grants of Bengal.

- Inserting Brahmana Donees: This indicates that grants typically integrated Brahmana donees into pre-existing social, economic, and cultural frameworks rather than creating entirely new settlements.

Brahmadeya Land Grants Overview

- Brahmadeya land grants could vary significantly in size, ranging from small plots to entire villages or even multiple villages.

- The number of recipients, or donees, could range from a single Brahmana to hundreds of them.

- There are instances where a single donee received multiple gifts.

Large Grants to Brahmanas

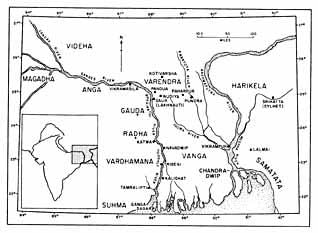

- An example of a vast area being granted to a large number of Brahmanas is found in the 10th-century Pashchimbhag plate of Srichandra from Bengal.

- This inscription records a grant to 6,000 Brahmanas, along with several individuals associated with a matha (monastery) dedicated to the god Brahma and a temple of Vishnu.

- The grant included three vishayas (districts) in Shrihatta mandala within Pundravardhana bhukti, which were transformed into a brahmapura (Brahmana settlement) named Shrichandrapura in honor of the king.

- The boundary details of these grants suggest that brahmadeyas (Brahmana settlements) were sometimes contiguous, indicating a trend of increasing number and density of Brahana settlements in certain areas.

Tax-Free Status

- The majority of land grant inscriptions conferred a permanent tax-free status to the Brahmana settlements.

- This meant that the land was exempt from state taxes, and any dues that the state might have been entitled to levy were now to be paid to the donee.

- Brahmadeyas enjoyed a special revenue status, with the right to collect and retain revenue vested in the donees.

Kara-shasanas and kraya-shasanas

Kara-shasanas are land grant inscriptions that specify the land was subject to taxes, unlike the usual tax-exempt grants. These are rare and have been found in regions like Orissa, Bengal, and Andhra Pradesh.

- Examples from Orissa:

- Bobbili plates of Chandavarman: The grant stipulated an annual payment of 200 panas for the village, similar to other agraharas.

- Ningondi plates of Prabhanjana-varman: Dues for the land were set at 200 panas to be paid in advance.

- Ganjam grant of Prithivarmadeva: Land was granted with a tax requirement, specifying an annual rent of 4 palas of silver.

- Gangas of Kalinganagara: Various grants indicating specific rent amounts and payment periods, such as the Kalahandi grant of Vajrahasta and the Chicacole grant of Anantavarman.

- Bhauma-Kara queen Dharmamahadevi: The Angul plate suggesting a mix of tax-free and taxable land grants.

- Shulki inscriptions: Talcher and Puri plates indicating specific tax amounts despite standard tax-free language.

- Tunga ruler Gayadatunga: Talcher plate and Asiatic Society plate detailing tax amounts and the nature of the land grant.

- Somavamshi king Janamejaya Mahabhavagupta: Patna plates specifying annual tax amounts.

- Imperial Gangas: Grants lacking explicit tax-free references, suggesting potential tax obligations.

Rights of the Donees:

- Proceeds of Fines: Donees were entitled to the proceeds from fines imposed on individuals found guilty of specific criminal offenses.

- Immunity from Punishment: Another interpretation suggests that donees were granted immunity from punishment if they committed such crimes themselves.

- Right to Try Accused Individuals: Some inscriptions indicate that donees had the right to try individuals accused of certain offenses.

Sa-Chauroddha-Rana:

This term can be understood in two ways:

- Right to Punish: Referring to the right to punish those found guilty of theft.

- Right to Realize Fines: Referring to the right to realize fines from those guilty of theft.

Authority of the Donees:

- Inscriptions from different regions show the extensive authority granted to donees.

- Example from Orissa: Inscriptions from Orissa mention land grants that include habitat land and forest (sa-padr-aranya) to the donees.

- Comparison with Bengal: This practice is similar to post-12th century inscriptions in Bengal that transferred rights over habitat land (vastu-bhumi) to donees.

Control Over Village Outposts:

- Inscriptions of Orissa: From the 9th century onwards, some inscriptions in Orissa (such as those of Udayavaraha and the Bhauma-Kara, Shulki, and Tunga dynasties) stated that land was granted along with control over village outposts, landing or bathing places, and ferries (sa-kheta-ghatta-nadi-tara-sthan-adi-gulmaka).

- Interpretation: This can be understood as granting rights over dues collected at these locations or rights over military outposts.

Granting of Subjects:

- Inscriptions of Bhauma-Karas, Adi-Bhanjas, Shulkis, and Tungas: Some inscriptions mention land grants ‘along with weavers, cowherds, brewers, and other subjects’ (sa-tantravaya-gokuta-shaundik-adi-prakritika).

- Transfer of Sharecroppers: In Karnataka, certain land grants indicate the transfer of sharecroppers (addhikas) along with the land.

Restriction on Alienation:

- Inalienability of Gifted Land: Many donees did not have the right to alienate land, meaning they could not transfer, sell, or dispose of it in any way.

- Terms Indicating Inalienability: The inalienability of gifted land is indicated by terms such as nivi-dharma, akshaya-nivi-dharma, or aprada-dharma.

- Orissa Inscriptions: Several inscriptions from Orissa contain the term a-lekhani-praveshataya, meaning the land could not be the subject of another document and could not be sold.

- Rights of Brahmana Donees: In such cases, the rights of Brahmana donees over the gifted land were greater than those of a landlord but less than those of a landowner.

The Effect of Brahmana Settlements on Agrarian Relations

Brahmana settlements in South India during the early medieval period had a significant impact on agrarian relations and the rights of various rural groups. Here are the key points regarding this impact:

1. Royal Patronage and Brahmana Elite

- Royal support enhanced the economic power of certain Brahmana communities, leading to the emergence of a Brahmana landed elite.

- This elite should not be confused with ‘Brahmana feudatories’ or ‘Brahmana intermediaries,’ as they were not military servants or tax collectors for kings.

2. Agrarian Expansion and Land Grants

- Historians generally view the early medieval period as one of agrarian expansion, with land grants playing a crucial role.

- However, there are differing opinions on the nature of agrarian relations during this time.

3. Impact on Rural Community Rights

- The establishment of brahmadeyas (Brahmana settlements) raised questions about the rights of different sections of the rural community, including large and small peasant proprietors, tenants, sharecroppers, and landless laborers.

- The long lists of exemptions (pariharas) found in land grant charters have led to debates about whether they indicate increasing oppression of the peasantry.

4. Different Historical Perspectives

- The feudalism school argues that land grants resulted in greater subordination and oppression of rural groups by Brahmana donees (beneficiaries of land grants).

- Burton Stein proposed the idea of a Brahmana-peasant alliance in early medieval South India.

- Proponents of the ‘integration’ or ‘processual’ model have not extensively addressed the nature of agrarian relations in this context.

5. Changes in Agrarian Relations

- The introduction of Brahmana donees into village communities altered agrarian relations, weakening older kinship-based production relations.

- Brahmana settlements often involved the use of non-family labor, further eroding kinship ties in production.

6. Tax-Free Status and Village Dues

- Most land grants included a tax-free status, requiring villagers to hand over various dues to the donees instead of the state.

- Inscriptions sometimes referred to taxes in general terms or specified long lists of tax exemptions, indicating a shift in tax responsibilities.

7. Rights Over Resources

- Donees were often granted rights over water resources, trees, forests, and habitation areas, impacting the rights of the village community.

8. Dispute Resolution and Judicial Rights

- Most village-level disputes were likely settled by a section of the village community.

- Inscriptions suggesting the transfer of judicial rights or the right to collect fines for criminal offenses indicate changes in the rights of this section of the community.

Land Grants and Their Impact on Society

- Historical Processes: B. D. Chattopadhyaya identified key historical processes in Indian history, including state expansion, tribe transformation, caste formation, and cult appropriation during the early medieval period.

- Strengthening Brahmanas: Land grants reinforced the position of some Brahmanas in rural areas, enhancing their traditional high social status with political and economic power. This granted them control over land, resources, and people, making them a dominant caste in brahmadeya villages.

- Interaction with Tribal Communities: In regions where brahmadeya villages were near tribal communities, land grants facilitated the introduction of plough agriculture to these tribes. Some tribal groups were integrated into caste society, while others were marginalized as outcastes or untouchables.

- Caste Formation and Kayasthas: The phenomenon of land grants contributed to the proliferation of castes, including the transformation of kayasthas (scribes) from an occupational group into a caste due to the need for recording numerous land transactions.

- Impact on Brahmanas: The increase in land grants led to the emergence of regional classifications and status hierarchies among Brahmanas. They were drawn into new social networks, resulting in the formation of sub-castes, especially among migrant Brahmanas.

- Temple Religion and Sub-Castes: In regions like Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, engagement with temple religion gave rise to sub-castes such as the Shiva Brahmanas, associated with Shiva temples.

- Modification of Marriage Practices: Integration into local societies sometimes led to changes in marriage practices among Brahmanas. For instance, in Kerala, the Brahmanas of Payyanur adopted matrilineal practices, while the Nambudri Brahmanas developed a unique custom of marrying within their caste to maintain property, reflecting the influence of the Nayar matrilineal society.

- Rise of Temple-Based Sectarian Religion: The early medieval period witnessed the growing popularity of temple-based sectarian religion, especially from the 10th century, with increased royal patronage of temples.

- Brahmanas and Temple Management: Some Brahmanas adapted their roles to the temple environment, becoming temple managers or priests. Inscriptions from South India indicate the active involvement of Brahanas and Brahmana sabhas in temple management, with Brahana settlements in Kerala being temple-centered from early times.

- Spread of Temple-Oriented Religion: Despite inscriptions emphasizing their Vedic affiliations, Brahmanas of the brahmadeyas likely played a significant role in spreading temple-oriented religion during this period.

Interaction between Brahmanical and Tribal Cultures

- Brahmadeyas located in or near tribal areas served as points of interaction between Brahmanical and tribal religions, leading to various forms of religious synthesis.

- Exposure and Transformation: Tribal communities were introduced to Brahmanism, while Brahmanism was also transformed through its interaction with regional, local, and tribal traditions.

- Migration and Marriages: During times of migration, marriages between Brahmanas and local women may have further facilitated the interaction between Brahmanical and tribal cultures.

- Reciprocal Interaction: The interactions were mutual, but not equal or balanced, with Brahmanical elements eventually becoming dominant.

- Example of Jagannatha: The cult of Jagannatha in Orissa illustrates the Brahmanization of a tribal deity, as analyzed by various scholars.

- Role of Land Grants in Tantra: R. S. Sharma suggested that the interaction between Brahmanical and tribal cultures through land grants was significant in the emergence and development of Tantra.

Land Grants, Brahmanas, and Sanskrit Literature

- Early Medieval Period: The proliferation of land grants to Brahmanas during the early medieval period coincided with a significant output of Sanskrit literature.

- Employment Opportunities: The period saw increased employment opportunities for literate and learned Brahmanas in the administrative structures of expanding royal courts.

- Patronage in Royal Courts: Brahmana scholars, poets, and dramatists were celebrated and supported in these courts.

- Sustaining Scholarship: Patronage through land grants likely played a crucial role in promoting and sustaining Brahmana scholarship.

- Wealth and Security: Control of land and the emergence of settlements inhabited by Brahmana specialists provided sections of the Brahmana intelligentsia with the security and wealth necessary for sustained intellectual activity.

Rural Society: Regional Specificities

Historical Processes and Regional Specificities

- Historical processes have impacted the lives of villagers across different parts of the subcontinent.

- There is limited direct textual evidence regarding the details of rural life during this period.

The Krishi-Parashara

- The Krishi-Parashara is a significant text that focuses on various aspects of agricultural operations.

- It was likely composed in the Bengal region between 950 and 1100 CE.

- The text is attributed to an author named Parashara and is written in Sanskrit verse with some prose mantras.

- The language and style of the Krishi-Parashara are simple and straightforward.

Agricultural Practices in the Krishi-Parashara

- The text emphasizes the importance of rainfall in agriculture and provides maxims related to planetary movements, seasons, wind direction, and rainfall.

- It recommends using weathervanes to monitor weather conditions.

- The Krishi-Parashara highlights the significance of manure (sara) for a healthy paddy crop and offers detailed instructions on rice cultivation, including ploughing and sowing techniques.

Sowing and Transplanting Techniques

- Instructions for preserving seeds and the best times for sowing are provided.

- The text suggests using a tool called mayika for leveling rice fields after sowing.

- Guidelines for transplanting seedlings, including spacing based on planetary conjunctions, are also included.

Harvesting and Threshing

- The Krishi-Parashara outlines the harvest period (Pausha, December-January) and provides details for setting up a threshing floor.

- After harvesting and threshing, farmers are advised to weigh the grain using a measure called adhaka.

Popular Agricultural Sayings of Early Medieval Bengal

Early Bengali Literature

- The Bengali language was fully developed around 1000 CE, but there is very little surviving literature from before 1300 CE.

- The earliest works in Bengali include the Dak Tantra, also known as the Dakar Bachan, which is a Buddhist Tantric text containing wise sayings and aphorisms in old Bengali.

- Another similar work is the Khanar Bachan, which has undergone more changes over time. According to popular belief, Khana, the author of this work, was the daughter-in-law of the famous astronomer Varahamihira.

The Dakar Bachan and Khanar Bachan

- The sayings in the Dakar Bachan and Khanar Bachan are primarily focused on agricultural matters, but they also touch on topics like astrology, medicine, and domestic issues.

- These works consist of short, rhyming aphorisms that are closely related to the soil and climate of Bengal. Even today, they serve as valuable agricultural manuals for farmers in the region.

- The Dakar Bachan is associated with a figure known as ‘Dak’, who is often imagined as a humble milkman. The sayings are signed with ‘Dak goala’, reflecting this popular belief.

Translated Sayings

- Agrahayan Rain: If it rains in the month of Agrahayan (November–December), it is believed to bring misfortune, symbolized by the king going a-begging.

- Paush Rain: Rain in the month of Paush (December–January) is seen as highly beneficial, potentially allowing even the sale of chaff for profit.

- End of Magh Rain: Rain at the end of Magh (January–February) is considered a blessing for the king and his kingdom.

- Phalgun Rain: Rain in Phalgun (February–March) is believed to promote the abundant growth of millet, specifically chinakaon (Panicum miliaceum).

- Sun and Shade: Khana advises that paddy (rice) thrives in the sun, while betel (betel leaf) prefers shade.

- Ideal Conditions for Paddy: Khana emphasizes that paddy grows rapidly with plenty of sunshine during the day and showers at night, and that drizzling rain in Kartik (October–November) is especially beneficial.

- Smut of Paddy: A practical tip for ploughmen to put smut of paddy in a bamboo-bush near the root of shrubs to cover a larger area of land.

- Patol in Sandy Soil: Advice to plant patol (Trichosanthis dioeca) in sandy soil for good results.

- Mustard and Rye Seeds: Guidance on sowing mustard seeds close together and rye seeds at a distance.

- Cotton and Jute Plants: Instructions on planting cotton plants at a distance from one another and avoiding planting jute near cotton, as cotton plants cannot tolerate water from jute fields.

- Chaitra Mist and Bhadra Paddy: A warning that mist in Chaitra (March–April) and plenty of paddy in Bhadra (August–September) can lead to plagues and disasters.

Agricultural Knowledge and Rituals in Early Medieval Eastern India

The Krishi-Parashara, an ancient text, provides valuable insights into agricultural practices, rituals, and beliefs in early medieval eastern India, particularly regarding the cultivation of paddy and the timing of agricultural activities.

Weather Predictions and Their Significance

- The text offers various weather predictions based on specific atmospheric conditions during different months, which are crucial for planning agricultural activities.

- For example, a southern wind in Ashadh (June-July) indicates a forthcoming flood, while certain cloud formations suggest imminent rainfall.

- These predictions guide farmers in taking timely actions, such as constructing water-preserving ridges around fields.

Agricultural Rituals and Festivals

- The Krishi-Parashara also details various agricultural rituals and festivals that are believed to influence the success of farming.

- For instance, the go-parva (festival of cows) in Kartika (October-November) is said to ensure the health of cattle for a year.

- Additionally, the text emphasizes the importance of the hala-prasarana, the ceremonial first ploughing, in securing the fruits of agriculture.

Fertility Beliefs and Restrictions

- There are specific restrictions related to fertility beliefs, such as avoiding contact between collected seeds and women who are menstruating, barren, pregnant, or have recently given birth.

- The text also mentions the Ambuvachi, a period in Ashadha when the earth is believed to menstruate, and seeds should not be sown.

Rituals for Protecting Crops

- The Krishi-Parashara prescribes mystical mantras from Tantric texts for dispersing birds and animals from fields and preventing diseases in paddy fields.

Ceremonies and Deities in Agriculture

- Before harvesting paddy in Pausha (December-January), a ceremony called the pushya-yatra is recommended, involving feasting, dancing, music, and prayers to the sun.

- Various deities, including Prajapati, Shachi, Indra, Marut, Vasudha, and Lakshmi, are invoked during agricultural operations, with Lakshmi receiving the final prayer to ensure prosperity.

Village Life and Land Grants in Early Medieval Bengal and Bihar

- Inscriptions from early medieval Bengal and Bihar provide detailed information about village life, land grants, and agricultural practices.

- Villages, referred to as grama or pataka, were characterized by their homestead land (vastu) and marked boundaries, often defined by natural features like rivers, marshy land, and trees.

- Rice was the staple crop, and land grant inscriptions meticulously detailed the dimensions and annual revenue of gifted land, indicating careful state revenue record-keeping.

- The dimensions were given in surface and seed measures, reflecting the original calculations based on rice output.

- In the land grants from Bengal and Bihar, the recipients are typically identified as the cultivators (kshetrakarah) or the inhabitants (prativasinah) of the village.

- Brahmanas, particularly the chief among them (Brahmanottarah), are consistently mentioned, highlighting their significance at the village level. Some inscriptions also reference other groups, such as tradesmen, clerks, wage laborers, and village leaders. The term kutumbin is increasingly understood to mean farmer.

Early Medieval Inscriptions of Assam

- Nayanjot Lahiri’s study of early medieval inscriptions in Assam indicates that agricultural activities and settlements were primarily located in or near the valleys of the Brahmaputra and other rivers, with notable concentrations in areas like Tezpur and Guwahati.

- The inscriptions frequently mention rivers and streams in the context of village boundaries, underscoring the reliance on riverine water resources for agrarian villages. In contrast, the hills surrounding the Assam valley, such as the Mikir, Khasi, Garo, Singori, Haji, and Sualkuchi hills, are not referenced in the inscriptions.

- Besides rivers and streams, village boundaries are marked by features like agricultural fields, embankments, ponds, trees, roads, and other villages. Rice cultivation emerges as the predominant activity in these agricultural villages.

- The habitations, referred to as vastu, are described as being situated amidst clusters of bamboo and fruit trees, encircled by fields. Pasture land is sometimes found at the edges of agricultural land and may consist of fallow land that was previously under cultivation.

- Embankments for water management are commonly mentioned. In addition to rice, inscriptions list various fruits (such as jackfruit, figs, blackberries, mangoes, walnuts, and sweet root) and trees (including banyan, saptaparna, jhingani, odiamma, bamboo, and cane). Trees with commercial value, such as betel nut, sandalwood, and silk cotton, are noted, though they do not appear to have been cultivated in plantations.

Land Grants in Assam

- In Assam, as in other regions, kings granted land to Brahmanas. The rural community consisted of Brahmanas, tribal groups, and various other communities, including kaivarttas (traditionally linked to fishing and boating), potters, and weavers, indicating a mix of agricultural and craft activities.

- Household units were central to agricultural labor. After the 9th century, there was a noticeable increase in agricultural settlements focused on wet rice cultivation, likely accompanied by population growth.

Role of Irrigation in Early Medieval Rajasthan

- Irrigation was crucial for the growth of agriculture in early medieval Rajasthan.

Sources of Irrigation

- Tanks and wells were the primary sources of artificial irrigation.

- Many 12th–13th century inscriptions from west Rajasthan, where water was scarce, reference various types of wells and tanks.

Types of Wells and Tanks

- Different types of wells mentioned in the inscriptions include:

- Dhimada/Dhivada : A type of well.

- Vapi : A step well.

- Araghatta/Araghata/Arahata : A type of well, possibly related to the Persian wheel.

- Tanks and reservoirs mentioned include: Tadaga, Tatakini, Pushkarini, etc.

- Some tanks were named after their builders.

Debate on the Persian Wheel

- The use of the Persian wheel in early medieval Rajasthan is debated among historians.

- The debate centers around the interpretation of the term Araghatta and whether it refers to the Persian wheel or the noria.

- The noria is a wheel with pots or buckets attached to its rim, used for drawing water from rivers or shallow sources.

- The Persian wheel, with gears and a chain to carry pots, was associated with wells.

- The Araghatta is believed to be similar to the Persian wheel, indicating its early use in India.

Crops and Agricultural Practices

- Inscriptions from Rajasthan mention various crops, including: Rice, Wheat, Barley, Jowar, Millet, Moong.

- Cash crops included Oilseeds (such as Sesame ) and Sugarcane.

- The practice of double cropping, or growing two crops a year, was suggested by inscriptions such as the Dabok inscription of 644 CE.

Control of Irrigation Resources

- Control over irrigation resources was held by various groups, including: Kings, Royal officials, Corporate bodies (such as Goshthis ), and Individual cultivators.

Expansion of Irrigation Works

- Irrigation works expanded in low rainfall areas of: North Gujarat, Saurashtra, Kutch, and South Rajasthan.

- The Aparaji-taprichchha of Bhuvanadeva, a 12th-century architectural work, mentions various sources of water for irrigation.

- Inscriptional references to irrigation increased from the 7th–8th centuries to the 11th–13th centuries.

- A significant number of tanks, wells, and step wells were constructed in the 12th–13th centuries by rulers, nobles, and merchants.

- The Chaulukyas of Anahilavada were active in building irrigation works and likely had an irrigation department.

Impact of Irrigation on Agriculture

- The expansion of irrigation facilities likely facilitated double cropping and the cultivation of various cash crops.

- Increased irrigation supported the cultivation of cash crops such as Sugarcane, Oilseeds, Cotton, and Hemp, which became important trade items between the 11th and 13th centuries.

Land Measures and Boundaries in Inscriptions

Inscriptions from Orissa, as noted by Singh in 1994, mention various terms related to land measurement, such as timpira, muraja, nala, hala, and mala. These terms reflect the different ways land was measured and categorized.

- The descriptions of land boundaries in these inscriptions often include a mix of languages, specifically Sanskrit, Oriya, and Telugu. This linguistic diversity indicates the cultural and regional influences in the documentation of land boundaries.

- Village boundaries were marked by natural and man-made features, including trees, rocks, anthills, trenches, rivers, hills, embankments, tanks, wells, and the boundaries and junctions of adjoining villages. These features served as important reference points for defining the limits of agricultural land and villages.

- When it comes to water resources, rivers and tanks are the most frequently mentioned, while wells appear less often in the inscriptions. The Achyutapuram plates of Indravarman highlight the importance of royal tanks (raja-tataka) by stating that the donee should not be obstructed when opening the sluice of the tank. This indicates the significance of these royal tanks in the context of gifted land.

- Rural Life and Agrarian Relations

- The specifics of rural life and agrarian relations in South India, including the various aspects of agriculture, land ownership, and community relations, will be discussed in greater detail later in the chapter.

Urban Processes in Early Medieval India

The idea of a decline of cities, urban crafts, trade and money in early medieval times is an important part of the hypothesis of Indian feudalism. In the previous chapter, there was reference to R. S. Sharma’s theory of a two-stage urban decay, one beginning in the second half of the 3rd or the 4th century, and the second one starting after the 6th century (Sharma, 1987).

- Sharma has summarized archaeological data from various regions to substantiate his theory. He admits that the Indian literary evidence for urban decay is not strong, but cites the accounts of Xuanzang and Arab writers. His explanation of urban decay centres around a supposed decline in long-distance trade.

- Urban decline undermined the position of urban-based artisans and traders; artisans were forced to migrate to rural areas; traders were not able to pay taxes; the distinction between town and village became blurred. Urban contraction was, however, accompanied by agrarian expansion.

- Elsewhere, Sharma ([1965], 1980: 102–5) cites epigraphic references to the transfer of rights over markets to donees, merchants transferring part of their profits to temples, and the transfer of customs dues from the state to temples. On this basis, he talks of a feudalization of trade and commerce. He argues that a mild urban renewal began in some parts of the subcontinent in the 11th century, and that urban processes were well-established by the 14th century.

- A revival of foreign trade—linked to an increase in the cultivation of cash crops, better irrigation techniques, increasing demand for commodities, improvements in shipbuilding and an expansion of internal trade—is cited as a major reason for the urban revival, as well as for the decline of the feudal order.

- As mentioned in Chapter 9, the hypothesis of urban decline can be questioned on various grounds. Chattopadhyaya (1986, 1997) has argued that the early medieval period saw the decline of certain urban centres, but there were others that continued to flourish, as well as some new ones that emerged.

- Xuanzang suggests that cities such as Kaushambi, Shravasti, Vaishali, and Kapilavastu were in decline. But he also mentions flourishing ones such as Thaneswar, Varanasi, and Kanyakubja. The archaeological data on the settlements of the period is patchy and inadequate. But some early historical cities continued to be inhabited during early medieval times, e.g., Ahichchhatra, Atranjikhera, Rajghat, and Chirand.

- Chattopadhyaya also marshalls epigraphic evidence from the Indo-Gangetic divide, the upper Ganga basin, and the Malwa plateau, with a special focus on the sites of Prithudaka (modern Pehoa in Karnal district, Haryana), Tattan-dapura (Ahar, near Bulandshahr, UP), Siyadoni (near Lalitpur in Jhansi district, MP), and Gopagiri (Gwalior).

- While Prithudaka may have been a semi-urban marketing centre, the other three clearly had an urban status in the 9th–10th centuries. Inferences about the continued vibrancy of city life can also be made on the basis of the numerous literary works and the sculpture and architecture, which must have been substantially, if not entirely, patronized by urban elites.

Trade and Monetary History in Early Medieval India

Monetary History:

- John S. Deyell's research indicates that money was not scarce in early medieval India, and states were not facing financial crises.

- There was a reduction in coin types and a decline in the aesthetic quality of coins, but the volume of coins in circulation remained stable.

- Deyell argues that the debasement of coinage did not indicate a financial or economic crisis. Instead, it could reflect increased demand for coins when the supply of precious metals was limited.

- North India faced a sustained shortage of silver around 1000 CE (and in some areas as early as 750 CE), necessitating the dilution of silver content in coins.

Trade Interactions:

- Traders in the Indian subcontinent were part of a broader network of trade connecting Africa, Europe, and various parts of Asia.

- From the 7th century onwards, the Arabs expanded their political control into northern Africa, the Mediterranean, central Asia, and Sindh. This gave them strategic control over Indian Ocean trade.

- The Arab conquests and the establishment of the Ummayid and Abbasid caliphates enabled Arab traders to become key players in trade routes connecting Europe with East Asia.

Maritime Trade:

- Texts like the 9th-century Ahbar as-Sin wa’l-Hind describe long maritime journeys by Arab traders from Oman to Quilon (Kollam) in Kerala and onto China.

- By the 11th century, Indian Ocean trade was segmented into smaller routes, with trade emporia emerging at the junction of these segments.

- Notable trade emporia included Aden, Hormuz, Cambay, Calicut, Satgaon, Malacca, Guangzhou, and Quanzhou.

- Commodities like silk, porcelain, sandalwood, and black pepper were significant in Asian trade, exchanged for items such as incense, horses, ivory, cotton textiles, and metal products.

- India’s maritime networks were oriented eastward towards China and East Asia, with Sri Lanka serving as an important hub in Indian Ocean trade.

Changes in Exports

- Before the 11th century, India primarily exported luxury items like textiles and spices.

- From the 11th century onward, exports expanded to include sugar, cotton cloth, leather goods, and weapons.

Use of Money and Bills of Exchange

- Gadahiya coins from the 7th to 12th centuries found in western India indicate the use of money in trade.

- Hundikas, or bills of exchange, were also used to facilitate large transactions without cash.

Toll Houses and Commercial Taxes

- Inscriptions mention toll houses (shulka-mandapikas), which were important for state income through commercial taxes.

Role of Merchants in Chaulukya Administration

Merchants held significant positions within the administrative framework of the Chaulukya dynasty, assuming crucial civic and military roles such as mahamatya (high officials) and dandadhipati (chief of police). Many traders in western India during this period were followers of Jainism. Jain texts, like the Shatsthanakaprakarana by Jineshvara Suri in the 11th century, outlined the ethical guidelines that Jain merchants were expected to adhere to.

- Merchants from Gujarat were not only known for their patronage of learning but also for their contributions to literature in areas such as kavya (poetry), poetics, philosophy, and grammar. Hemachandra, a prominent figure who authored several important Jain texts along with works on grammar, metrics, and philosophy, was the son of a merchant from Dhandhuka.

- These merchants made substantial donations for the construction of temples, wells, and tanks, with notable examples of such patronage seen in the temples at Mount Abu and Girnar. Inscriptions from the region also indicate that tolls and taxes levied on merchants were redirected to religious institutions for their upkeep and for the celebration of festivals.

Trade with Southeast Asia and China

During the early medieval period, India’s trade with Southeast Asia and China experienced significant growth. Tansen Sen (2003) observed a shift in Sino-Indian interactions from being predominantly Buddhist to trade-centered exchanges between the 7th and 15th centuries. By this time, China had become a major center for Buddhism, and the increasing Sinification of Chinese Buddhism, along with the rise of indigenous Chinese Buddhist schools, reduced the reliance on cultural transmission from India.

Sino-Indian trade links in the early medieval period can be categorized into three phases:

- 7th–9th centuries: This period saw a continued demand for Buddhist ritual items in the trade between India and China.

- 9th–10th centuries: Overland trade between India and China declined during this phase due to political instability in Central Asia and Myanmar.

- Late 10th century: Tributary and commercial relations were revitalized, leading to significant growth in both overland and maritime trade.

Xuanzang's Observations on Silk and Chinese Imports

Xuanzang, a Chinese monk, noted that silk was among the most favored materials for clothing in India. One of the Sanskrit terms for silk is kausheya, which likely referred to domestically produced silk. This was in contrast to china-patta or chinamshuka, which denoted Chinese silk or silk woven from Chinese yarn in India. Although India produced silk, it was generally not as fine as Chinese silk, leading to a continued demand for the latter.

- Silk fabric and garments were significant items brought to India by Chinese diplomatic missions and monks as gifts. However, by the 11th century, Chinese porcelain had surpassed silk as a major import into India.

- Some of this porcelain was further transported westward by traders to regions bordering the Persian Gulf and Red Sea, where it was also in high demand. Other Chinese products imported into India included hides, vermilion, fruits like pears and peaches, camphor, lacquer, and mercury.

Trade between China and India in the Early Medieval Period

Imports from India to China

- During the 11th century, the range of items imported by China from India expanded significantly.

- These imports included a variety of goods such as:

- Horses

- Frankincense

- Sandalwood

- Gharu wood

- Sapan wood

- Spices

- Sulphur

- Camphor

- Ivory

- Cinnabar

- Rose water

- Rhinoceros horn

- Putchuck

Origin of Goods

- Some items, like frankincense and rose water, originated in the Persian Gulf area and were transported eastwards from Indian ports.

- Others, such as various spices and woods, were sourced from India.

Indian Textiles

- By the end of the 13th century, Indian textiles had become one of the most significant exports from India to China.

Shift in Trade Routes

- The growing trade between China and India led to a re-orientation of trade routes.

- From the 8th century onwards, maritime routes between India and China were used more frequently than overland routes.

Maritime Routes

- One of the prominent sea routes passed through the Andaman and Nicobar Islands.

- Another route went through the Bay of Bengal ports, then to Sumatra and the South China Sea.

Technological Advancements

- The increased preference for sea routes was partly due to advancements in maritime technology.

- There was a shift from using sewn ships to more durable ships with nailed hulls, enhancing the safety and efficiency of maritime trade.

Diversification of Trade Commodities

- Indian trade in the early medieval period saw a diversification of trade commodities and links.

- An analysis of inscriptions from the Ayyavole guild indicates a shift in focus from luxury items to staples and basic goods.

Emerging Trade Goods

- Goods such as yarn, textiles, dyes, processed iron, pepper, and horses became more prominent in trade.

- In the mid-12th century, inscriptions began recording the import of large quantities of goods into South India from West Asia, Southeast Asia, and China.

Imported Goods

- Precious stones

- Pearls

- Perfumes

- Aromatics

- Myrobalans

- Honey

- Wax

- Textiles, including silk

- Spices

- Horses

- Elephants

Exported Goods

- Cotton textiles

- Spices, particularly pepper

- Iron

- Dyes

- Ivory

- Areca nuts

- Putchuck

Shift in Trade Dynamics

- From the 13th century onwards, the west coast of India became increasingly important for trade.

- Ports such as Quilon (Kollam) gained prominence, with Chinese Yuan emperors sending missions to this port.

Expansion of Trade Links

- The shift towards western ports in South India and Sri Lanka indicated an expansion of Indian trade links with regions such as Egypt and West Asia.

Role of Bay of Bengal Ports

- While early medieval maritime trade discussions often focus on Gujarat and South India, Bay of Bengal ports also played a role, albeit with less intensity.

- Tamralipti (Tamluk in Medinipur district) was the most important port in Bengal until the 8th century.

- Post-8th century CE, Samandar, likely located near Chittagong, rose to prominence and is frequently mentioned in Arab accounts.

Trade and Cultural Exchange

Khalakapatna

- Located on the Kushbhadra river in Puri district, Khalakapatna was a prominent port between the 11th and 14th centuries.

- Excavations uncovered Chinese celadon ware, porcelain, copper coins, and glazed pottery possibly from West Asia.

Manikapatna

- Situated on the channel connecting Chilka Lake with the Bay of Bengal, Manikapatna revealed a cultural sequence from the early historical period to the 19th century CE.

- Findings included Chinese pottery, celadon ware (both original and local imitations), and copper coins from China.

Migration of Trading Communities

- The early medieval period witnessed the migration of various trading communities.

- Arab and Persian traders were among the earliest groups to settle along the Konkan, Gujarat, and Malabar coasts.

- An inscription from 875 CE mentions the king of Madurai granting asylum to a group of Arabs, marking the first Arab settlement on the Coromandel coast.

- Arabic inscriptions found in Cambay, Prabhasapattana (Somanath), Junagadh, and Anahilavada indicate the presence of Arab shipowners and traders in Gujarat during the 13th century.

- A Jewish community also established itself in the Malabar area during this period.

Impact of Political Developments in West Asia

- Political changes in West Asia, particularly the Arab expansion, prompted the migration of Christians and Zoroastrian Persians (Parsis) to the Kerala coast.

Historical Processes in Early Medieval South India

The Nature of South Indian States

- The historiography of early medieval South India has evolved through various distinct phases. Nilakantha Sastri was among the early scholars who attempted to weave together scattered data from diverse sources into a cohesive historical narrative. However, his narrative was criticized for its nationalist bias and for glorifying the Chola state as a highly centralized empire.

- Burton Stein criticized traditional historiography in the 1960s, focusing on the Chola state’s relationship with society and the economy, particularly the agrarian order. He argued that earlier scholars inconsistently praised the Chola state as strong and centralized while also acknowledging robust local self-governing institutions.

Stein’s Alternative Model

- Sacral Kingship: Stein proposed that South Indian kingship was based on sacred authority rather than bureaucratic or constitutional principles. Kings had effective power primarily in core areas around their political centres, where they could exert control over people and resources.

- Segmentary State: The state was seen as segmentary, with kings acting more as ritual figures outside their core areas. Land revenue was collected from limited regions, and states relied on looting expeditions for sustenance.

- Peasant Society and Peasant State: Stein emphasized the role of peasant society and the peasant state in the functioning of early medieval South India. He argued that the Chola state lacked a bureaucratic machinery, a standing army, and a significant revenue collection system.

Critique of Stein’s Model

- While Stein’s critique of the Chola state was valid, his portrayal of early medieval South Indian kingship as purely sacral has been challenged. Critics argue that this view overlooks the enduring power and military success of dynasties like the Cholas.

- Exaggeration of Chola Power : Earlier scholars had exaggerated the power of the Chola state, but Stein’s alternative faced its own challenges. For instance, his emphasis on looting expeditions as the foundation of ancient Indian kingdoms was questioned.

- Different Political Systems : Stein’s examples of military expeditions by Samudragupta and petty cattle raiders in South India were seen as reflecting different types of political systems. While war and loot were integral to ancient and early medieval politics, the formation and persistence of empires like the Maurya, Gupta, Satavahana, and Chola dynasties indicated a more complex political landscape.

Southall distinguished between a unitary and a segmentary state:

- Unitary State: A political system with a central monopoly of power exercised by a specialized administrative staff within defined territorial limits.

- Segmentary State: A political system where specialized power is exercised within a pyramidal series of segments. These segments are tied together by their opposition to higher-level segments and ultimately defined by their joint opposition to adjacent unrelated groups.

Segmentary State

1. Territorial Sovereignty

- Recognized but limited and relative.

- Political authority is strongest near the center and weakens towards the periphery.

- Periphery often experiences a shift into ritual hegemony.

2. Centralized Government

- Centralized government exists with limited control over peripheral administrative areas.

3. Administrative Staff

- Specialized administrative staff at the center, replicated on a smaller scale at peripheral administrative sites.

4. Monopoly of Force

- Central authority claims monopoly of force to a limited extent and within a restricted range.

- Peripheral foci also possess legitimate but restricted types of force.

5. Subordinate Foci of Power

- Multiple levels of subordinate foci organized in a pyramid structure relative to central authority.

- Similar powers at each level with decreasing range.

- Peripheral authorities are scaled-down versions of central authority.

6. Flexibility of Peripheral Authorities

- Peripheral authorities have greater flexibility to change allegiance between different power pyramids.

- Segmentary states are flexible, fluctuating, and interlocking.

7. Dual Sovereignty

- Sovereignty consists of actual political control and ritual sovereignty.

- Multiple centres may exist, with some exercising political control and others providing ritual sovereignty.

8. Specialized Administrative Staff

- Specialized administrative staff at the center may have counterparts in lower segments.

9. Pyramidal Organization

- Relationship between centre and peripheral foci of power is identical in all cases.

- Complementary opposition exists among parts of the state as a whole and within constituent segments.

10. Conceptual Category

- Segmentary state is a conceptual category encompassing states with segmentation of power.

- Includes diverse states like the Alur tribal system and medieval European feudal states.

- Southall suggested identifying different varieties of segmentary states.

Administrative Structures in Early Medieval South India

The early medieval states of South India had a more complex and nuanced administrative structure than previously thought. They were not as weak as some historians suggested, nor as strong and centralized as others believed. The royal court was surrounded by important officials who played crucial roles in the administration.

- The king was assisted by advisers and priests, such as the Brahmana purohita and rajaguru in Chola inscriptions.

- The Pallavas and Cheras had their own councils of ministers, while the Pandyas had mantrins (ministers) who may have formed a council.

- Other high-ranking officials, like the adhikari, vayil ketpar, and tirumandira-olai, had uncertain roles but were closely associated with the king.

Expansion of Administrative Structure

- Research by Karashima, Subbarayalu, and Matsui shows that the Chola inscriptions have more terms for offices and officials than those of the Pallavas, Pandyas, and Cheras.

- This indicates an expansion of the administrative structure, especially during the reign of Rajaraja I (985–1016).

- However, after Kulottunga I (1070–1122), there was a decline in such references, suggesting a reversal in this expansion.

Titles and Functions of Officials

- Individuals associated with administrative offices had various titles, such as araiyan, an honorific for important people.

- Some officials, like udaiyan, velan, and muvendavelan, were landowners and held specific roles in the administration.

Local Administration

- At the local level, officials like the nadu-vagai, nadu-kakani-nayakam, nadu-kuru, and kottam-vagai had overlapping duties, and there was a hereditary element in official appointments.

- The Cholas had a land revenue department responsible for maintaining accounts, while the assessment and collection of revenue were handled by corporate bodies like the ur, nadu, sabha, and nagaram, and sometimes by local chieftains.

Land Survey and Assessment

- During the reign of Rajaraja I, the Chola state embarked on a massive project of land survey and assessment, reorganizing the empire into units known as valanadus.

- Subsequent surveys were conducted during the reign of Kulottunga I, and in the post-Rajaraja period, the revenue department was known as puravu-vari-tinaikkalam or shri-karanam.

Land Revenue and Taxes in Early Medieval South India

- Inscriptions from the early medieval period in South India reveal various terms related to dues imposed by the state on cultivators. These terms indicate the obligations of villagers to provide food and labor services to state officials.

- Terms like Eccoru referred to the obligation of villagers to provide food for state officials, while Muttaiyal and vetti indicated the obligation to provide labor services. Kudimai was another term for such labor services.

- In the early Chola period, several land revenue terms were in use, including puravu, irai, kadan/kanikkadan, and opati. However, Kadamai became the most important land revenue term in the later Chola period. Its precise rate is uncertain, but it may have been as high as 40 to 50 percent of the produce and was likely collected in kind.

- The antarayam was a rural tax realized in cash. There was a noticeable increase in the number of revenue terms in inscriptions, peaking during the reign of Rajendra II (1052–63 CE) and declining from the time of Kulottunga I.

Military Organization

- The military expeditions undertaken by the kings of early medieval South India suggest an effective army organization, although details about it are limited. The personal bodyguards of kings and chieftains were connected to their lords through loyalty and hereditary ties, and they were likely assigned land revenue tasks.

- There was some form of standing army maintained by the state, with important military officers such as senapati and dandanayakam playing key roles. Chola inscriptions mention several military contingents, and the standing army was supplemented by periodical levies of troops from chieftains when necessary.

- The expeditions to Sri Lanka during the reign of Rajaraja I and the Shri Vijaya expedition during the reign of Rajendra I are often cited as evidence of a Chola navy. However, it is unclear whether this was a regular, separately recruited naval force or instances of transporting armed forces across oceans.

Administration of Justice

- Scholars have suggested the existence of a central or royal court of justice called the dharmasana during this period, reflecting the idea that the king was the highest court of appeal. However, the day-to-day administration of justice was likely handled by various local bodies, such as the sabha.

|

110 videos|653 docs|168 tests

|

FAQs on Emerging Regional Configurations, c. 600–1200 CE - 2 - History for UPSC CSE

| 1. What were the major regional configurations that emerged between 600 and 1200 CE? |  |

| 2. How did trade influence the regional configurations during this period? |  |

| 3. What role did religion play in the formation of regional identities during 600-1200 CE? |  |

| 4. What were the impacts of the Viking invasions on regional configurations in Europe during this period? |  |

| 5. How did the political landscape change in Asia between 600 and 1200 CE? |  |