UPSC Mains Answer PYQ 2024: Philosophy Paper 1 (Section- A) | Philosophy Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Section - A

Q1: Answer the following questions in about 150 words each: (10 × 5 = 50 Marks)

(a) Differentiate between Plato's and Aristotle's conceptions of form.

Ans: The concept of “Form” plays a central role in the philosophies of Plato and Aristotle, but their interpretations differ significantly. While both philosophers sought to understand the nature of reality and knowledge, their approaches diverged in metaphysical and epistemological terms. Plato introduced the concept of "Theory of Forms", whereas Aristotle developed a more immanent and empirical understanding of forms.

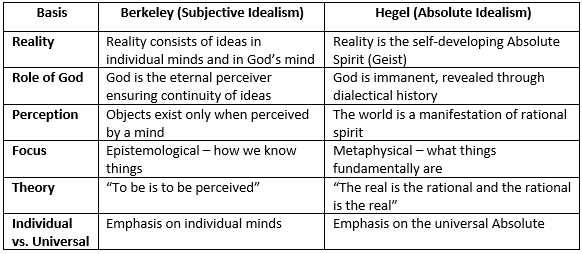

Difference between Plato’s and Aristotle’s Conception of Form:

Case Study / Theory:

In his dialogue “Republic,” Plato uses the Allegory of the Cave to illustrate the world of Forms as the ultimate truth, whereas in “Metaphysics,” Aristotle critiques Plato’s separation of form and matter, arguing that such separation makes the concept of change and causation unintelligible.

Plato and Aristotle laid the groundwork for Western metaphysics, but their conceptions of form diverged fundamentally. Plato emphasized transcendence and idealism, while Aristotle focused on empirical reality and form as an intrinsic principle. Aristotle’s view paved the way for modern science, while Plato’s idealism influenced rationalist traditions.

(b) How does Kant respond to Hume's scepticism with regard to a priori judgments? Discuss.

Ans: David Hume challenged the possibility of metaphysical knowledge by questioning the causal connection and rejecting the certainty of a priori knowledge. He argued that all knowledge comes from experience, casting doubt on causality and necessity. In response, Immanuel Kant, awakened by Hume’s scepticism, developed a Copernican Revolution in philosophy, asserting that synthetic a priori judgments are possible and necessary for knowledge.

Kant’s Response to Hume’s Scepticism:

Distinction of Judgments:

Kant categorized judgments into:

Analytic a priori (true by definition),

Synthetic a posteriori (empirical), and

Synthetic a priori (informative and necessary).

Kant argued that mathematics and natural sciences rely on synthetic a priori judgments.

Causality as a Category of Understanding:

Hume claimed causality is a habit formed through repeated experience.

Kant countered that causality is a necessary condition for experiencing events in a temporal sequence.

He called it a category of understanding, not derived from experience but imposed by the mind to make sense of experience.

Transcendental Idealism:

Kant proposed that our knowledge is of phenomena (appearances), not noumena (things-in-themselves).

Our mind structures experiences using space, time, and categories like causality—these are a priori intuitions.

Theory in Focus:

In “Critique of Pure Reason”, Kant asserts that human cognition actively shapes experience.

Without a priori categories, the world would be a “blooming, buzzing confusion.”

Examples:

Mathematics: “7 + 5 = 12” is not analytically true (not contained in the concepts), but it is necessarily true and known a priori.

Causality: When we see a ball breaking a window, we assume a causal connection not from habit (as Hume would say), but because our mind structures it that way.

Kant addressed Hume’s scepticism by proposing that synthetic a priori knowledge is possible through the mind’s inherent structuring faculties. This response preserved the possibility of metaphysics and scientific knowledge. Kant’s philosophy was pivotal in bridging rationalism and empiricism, shaping modern epistemology and metaphysics.

(c) What arguments are offered by Moore to prove that there are certain truisms, knowledge of which is a matter of common sense? Critically discuss.

Ans: G.E. Moore, a prominent analytic philosopher, is known for his defense of common sense realism. In response to philosophical skepticism, especially about external world knowledge, Moore introduced the concept of “truisms”—statements so evident that denying them seems irrational. His aim was to demonstrate that certain common sense beliefs are more rational than philosophical doubts.

Moore’s Arguments for Common Sense Truisms:

The Proof of the External World:

In his essay “Proof of an External World” (1939), Moore famously held up his hands and said: “Here is one hand, here is another”—proving the existence of two external objects.

He claimed this was a rigorous philosophical proof, grounded in common sense knowledge.

Characteristics of Truisms:

Moore identified truisms like:

“The Earth has existed for many years.”

“Other people have minds.”

“My body has existed in the past.”

These are basic certainties, intuitively known and immune to skeptical doubt.

Shift in Burden of Proof:

Moore turned the table on skeptics: rather than proving the external world exists, he challenged them to disprove the immediate certainty of everyday beliefs.

Knowledge vs. Proof:

Moore distinguished between knowing something and being able to prove it. One can know the external world exists without formal philosophical proof.

Examples: If a skeptic says we can’t be sure of other minds, Moore counters that he knows his friend is in pain because he hears him scream—common sense outweighs abstract doubt.

Critical Discussion:

Strengths:

Moore's arguments are accessible and grounded in ordinary experience.

His appeal to common sense provides a solid rebuttal to radical skepticism.

Criticisms:

Ludwig Wittgenstein and others argued that Moore’s “certainty” lacks context—saying “I know” needs criteria for its use.

Philosophical proof requires more than assertion—it demands coherence within a system of justification.

Critics argue Moore presupposes what he sets out to prove—the reality of external objects.

Moore's defense of common sense truisms remains influential for its simplicity and clarity. While not a definitive philosophical refutation of skepticism, it reasserts the primacy of lived experience and challenges overly abstract doubt. His work laid the groundwork for later ordinary language philosophy and inspired deeper inquiries into epistemic justification.

(d) Why does later Wittgenstein think that there cannot be a language that only one person can speak - a language that is essentially private? Discuss.

Ans: In his later work, particularly “Philosophical Investigations” (1953), Ludwig Wittgenstein rejected the idea of a private language, i.e., a language understandable by only a single individual referring to their own private sensations. His Private Language Argument (PLA) is a critique of Cartesian inner experience and solipsism, grounded in his broader philosophy of language as a rule-governed public activity.

Key Points in Wittgenstein’s Rejection of Private Language:

Language as Rule-Governed:

Language operates through rules that must be publicly accessible and shared.

A private language lacks the possibility of external correction or verification, making it incoherent.

Private Experiences Need Public Criteria:

One may feel pain, but the concept of “pain” only has meaning because it is taught and applied publicly.

Without public language games, the private sensation is meaningless as a linguistic term.

Memory and Error:

If one tried to record private sensations using a sign (say “S”), how could they know they are using it consistently?

Without external checks, one cannot distinguish remembering correctly from believing wrongly.

Meaning as Use:

Wittgenstein asserts: “The meaning of a word is its use in the language.”

If there is no shared use, there is no meaning.

Example: Imagine inventing a word for a sensation only you feel and never describing it to others. According to Wittgenstein, you can’t even know if you’re using the word consistently—it becomes a hollow gesture.

Critical Evaluation:

Support:

Emphasizes language as a social phenomenon.

Deflates metaphysical speculations about ineffable inner experiences.

Criticism:

Some philosophers argue that self-expression or introspective experience can have meaningful private content, even if not fully communicable.

Wittgenstein’s rejection of a private language underscores the inherently social nature of meaning. Language is not a mirror of inner thoughts but a public tool shaped by context and interaction. His insights reshaped debates in philosophy of mind, language, and epistemology.

(e) How does Kierkegaard define truth in terms of subjectivity? Critically discuss.

Ans: Søren Kierkegaard, a Danish existentialist, revolutionized the concept of truth by emphasizing subjectivity. In contrast to traditional notions of objective, propositional truth, Kierkegaard introduced the idea that truth is found in one’s passionate inward relationship with existence, especially in relation to faith and God.

Kierkegaard's Conception of Subjective Truth:

Truth as Subjectivity:

For Kierkegaard, “truth is subjectivity”—meaning that how one relates to truth is more important than the content of that truth.

Truth is not merely knowing propositions but living them passionately.

Objective vs. Subjective Truth:

Objective truth is factual, external, and dispassionate (e.g., mathematical facts).

Subjective truth involves commitment, risk, and authenticity—especially in matters of faith and ethics.

The Knight of Faith:

In Fear and Trembling, he presents the figure of Abraham, who, by being willing to sacrifice Isaac, shows absolute commitment beyond reason—demonstrating subjective truth.

Stages of Life:

Kierkegaard outlines three stages:

Aesthetic (pleasure-driven),

Ethical (moral responsibility),

Religious (faith in the absurd).

Only in the religious stage does one encounter subjective truth in its fullest.

Example: Saying “God exists” may be an objective proposition, but for Kierkegaard, what matters is how a person lives in relation to that belief—whether it transforms their life.

Critical Evaluation:

Support:

Highlights the importance of authenticity, passion, and existential engagement.

Influential in existentialism (Sartre, Camus) and theology (Tillich, Bultmann).

Criticism:

Risks relativism—if all truth is subjective, how can we criticize false beliefs?

May devalue objective knowledge, especially in science or logic.

Kierkegaard redefined truth not as a static proposition but as a lived commitment, rooted in passion and inwardness. His view is a powerful critique of detached rationalism, emphasizing that in the most crucial matters of existence, how one believes matters more than what one believes. His philosophy remains vital in existential thought and religious inquiry.

Q2:

(a) Is rejection of Locke's notion of primary qualities instrumental in Berkeley's leaning towards idealism? In this context, also discuss how Berkeley's subjective idealism is different from the absolute idealism proposed by Hegel. (20 Marks)

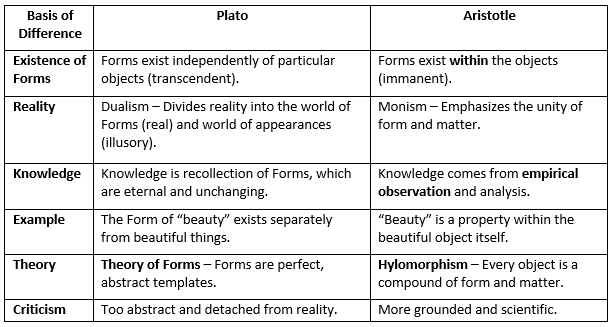

Ans: George Berkeley, an 18th-century Irish philosopher, advanced subjective idealism, asserting that physical objects only exist as ideas in minds. His rejection of John Locke’s distinction between primary and secondary qualities laid the foundation for this view. Later, G.W.F. Hegel developed absolute idealism, differing significantly from Berkeley’s approach. The comparison illustrates key developments in the idealist tradition.

Berkeley’s Rejection of Locke’s Primary-Secondary Quality Distinction:

Locke’s Distinction:

Primary qualities (shape, size, motion) are objective and exist in the object.

Secondary qualities (color, taste, sound) are subjective and exist in the mind.

Berkeley’s Rebuttal:

Berkeley argued that all qualities are perceived, including primary ones.

Even shape or motion changes depending on the observer's perspective.

Therefore, nothing exists outside perception: “Esse est percipi” – “To be is to be perceived.”

Idealism as a Consequence:

Rejecting material substance, Berkeley claimed that only minds and ideas exist.

Material objects are collections of ideas, sustained by the divine mind (God).

Example: A tree falling in the forest does not exist unless perceived. Its form, color, or size are all dependent on a perceiving subject.

Difference between Berkeley’s Subjective Idealism and Hegel’s Absolute Idealism:

Berkeley's rejection of Locke's primary qualities directly leads to his immaterialist ontology, where perception is central to existence. This subjective idealism, however, contrasts sharply with Hegel’s systematic metaphysical idealism, which seeks to explain reality as a self-unfolding rational whole. While both are forms of idealism, they operate at very different levels of abstraction and scope.

(b) How does Spinoza establish that God alone is absolutely real with his statement - "Whatever is, is in God"? Critically discuss. (15 Marks)

Ans: Baruch Spinoza, a rationalist philosopher, proposed a monistic metaphysics where God and Nature (Deus sive Natura) are identical. In his Ethics, Spinoza famously declared: “Whatever is, is in God, and nothing can be apart from God.” This statement reflects his idea that God is the only substance, and all finite things are modes or expressions of God’s essence.

Spinoza’s Argument for God as Absolute Reality:

Definition of Substance:

Substance is that which exists in itself and is conceived through itself.

There can be only one such substance – God.

Attributes and Modes:

God has infinite attributes, but humans can know only thought and extension.

Everything else (humans, objects, ideas) are modes, or modifications of God’s attributes.

Immanence of God:

Unlike theistic views where God is transcendent, Spinoza’s God is immanent—all things exist in God.

Causal Necessity:

God is the cause of all things – not by will, but by necessity of nature.

Every event follows from God's essence with mathematical necessity.

Example: A tree is not separate from God but a mode of the attribute of extension. A thought is a mode of God’s attribute of thought. Both exist in God, not outside of Him.

Critical Discussion:

Strengths:

Spinoza’s system is coherent, logical, and eliminates the problem of dualism.

Offers a naturalistic, scientific view of God—making the divine accessible.

Criticisms:

Pantheism: Critics like Leibniz accused Spinoza of equating God with the material world, thus removing divine personality.

Determinism: Spinoza’s system denies free will, making human agency problematic.

The concept of immanent divinity is incompatible with personal religious faiths.

Spinoza’s assertion that “Whatever is, is in God” reflects his radical redefinition of God as the only substance, the foundation of all that exists. While his system is logically consistent and influential, it has been both praised for its rational clarity and criticized for its denial of personal divinity and free will. Spinoza stands as a unique figure in the history of metaphysics and theology.

(c) Critically examine Kant's objections against the ontological argument for the existence of God. (15 Marks)

Ans: The ontological argument, originally formulated by Anselm of Canterbury, seeks to prove God’s existence purely through reason. It claims that God, defined as the greatest conceivable being, must exist—because existence is a necessary attribute of perfection. Immanuel Kant, in his Critique of Pure Reason, launched a powerful critique against this argument, reshaping theological and philosophical discussions on God.

Kant’s Objections to the Ontological Argument:

Existence is Not a Predicate:

Kant argues that existence adds nothing to the concept of a thing.

Saying “God exists” does not increase the concept of God—it only posits the concept in reality.

Just as 100 real coins and 100 imagined coins share the same concept, existence doesn’t make a being greater.

Analytic vs. Synthetic Judgments:

Ontological arguments treat God's existence as analytic (true by definition).

Kant insists that existence claims are synthetic a posteriori—verified through experience, not logic.

The Idea of Necessary Being:

The ontological argument treats God as a necessary being.

Kant questions the very coherence of “necessary existence”—saying we cannot infer reality from conceptual necessity.

Example: Defining God as “a being who must exist” doesn’t prove existence—just like defining a unicorn as “a horse with a horn that exists” doesn’t make it real.

Critical Evaluation:

Strengths of Kant’s Critique:

Dismantles the logical leap from definition to existence.

Reinforces the divide between conceptual analysis and empirical reality.

Criticisms:

Some modern philosophers (e.g., Alvin Plantinga) argue that Kant misunderstood the ontological argument’s modal logic.

Others maintain that Kant’s view may not apply to a maximally great being in modal terms.

Kant’s critique of the ontological argument remains one of the most influential challenges in the philosophy of religion. By rejecting existence as a predicate and emphasizing the limits of pure reason, Kant redirected theological inquiry toward practical reason and moral faith, rather than logical proofs of God’s existence.

Q3:

(a) Explain Russell's notion of incomplete symbols. Also explain how this notion leads to the doctrine of logical atomism. (20 Marks)

Ans: Bertrand Russell, a key figure in analytic philosophy, introduced the notion of incomplete symbols as part of his theory of descriptions. This concept plays a crucial role in his broader metaphysical framework of logical atomism, which aims to understand reality through logical structures and atomic facts.

Incomplete Symbols:

Definition:

Incomplete symbols are linguistic expressions that do not refer to any entity on their own.

Their meaning is derived only through contextual analysis or logical reconstruction.

Examples:

Phrases like “the present king of France” or “a man” are incomplete symbols.

They seem to refer to objects, but no object corresponds directly to them in reality.

According to Russell’s Theory of Descriptions, the sentence:

“The present king of France is bald” is neither true nor false, because it implies existence.

Logical Function:

Incomplete symbols help in eliminating metaphysical confusions.

They allow for a logical analysis of language, focusing on structure over reference.

Link to Logical Atomism:

Logical Atomism:

Reality consists of atomic facts—indivisible and logically independent.

Language mirrors reality, so analysis of language helps understand the structure of the world.

Role of Incomplete Symbols:

Incomplete symbols clarify language, helping isolate elementary propositions.

They prevent ontological commitments to fictional or ambiguous entities.

Example:

“A man walked in” becomes: “There exists an x such that x is a man and x walked in.”

No need to posit “a man” as a real object—only logical form matters.

Russell’s notion of incomplete symbols is central to his program of logical analysis, helping eliminate metaphysical excesses by focusing on logical form over grammatical appearance. This conceptual tool is instrumental in building his logical atomism, where language serves as a guide to reality through elementary facts and propositions.

(b) Is the sentence "All objects are either red or not red" meaningful in the same way as "This page is white" is, according to the logical positivists? Discuss with arguments. (15 Marks)

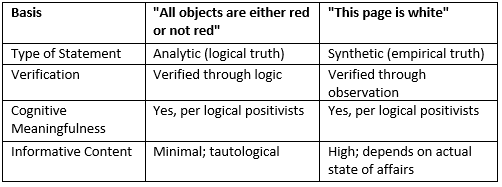

Ans: Logical positivists, associated with the Vienna Circle, proposed the verification principle—a statement is meaningful only if it is empirically verifiable or analytically true. Using this criterion, they distinguished between cognitively meaningful statements and pseudo-statements.

Analysis of the Two Statements:

“All objects are either red or not red”:

This is a tautology, i.e., a logically true statement.

Its truth can be established independently of experience, purely by logic.

It is analytically true and hence meaningful under logical positivism.

“This page is white”:

This is a synthetic statement.

Its truth depends on empirical observation.

It is verifiable in principle, thus also meaningful.

Comparison in Terms of Meaning:

Critical Perspective:

Some philosophers argue that tautologies, while meaningful, do not convey new knowledge.

The verification principle itself has been criticized for being self-defeating, as it is not empirically verifiable.

According to logical positivists, both statements are meaningful, though in different ways. The first is meaningful as a logical tautology, while the second is meaningful as an empirically verifiable claim. The distinction highlights the logical positivist emphasis on syntactic and semantic clarity in evaluating philosophical propositions.

(c) Among the rationalists, whose account of mind-body problem is compatible with the notion of human freedom and free will? Critically discuss. (15 Marks)

Ans: The mind-body problem questions how mental and physical substances interact. Rationalists like Descartes, Spinoza, and Leibniz offered distinct views. Of these, Leibniz’s theory stands out for preserving both rational determinism and a version of human freedom.

Rationalist Approaches to Mind-Body Problem:

Descartes (Substance Dualism):

Mind and body are distinct substances.

Allows space for free will, but struggles with interaction problem.

Spinoza (Substance Monism):

Only one substance (God/Nature) exists; mind and body are attributes.

Offers deterministic worldview, leaving little room for freedom.

Leibniz (Monadology):

Universe made of monads—simple, immaterial substances.

Pre-established harmony ensures coordination without interaction.

Leibniz and Free Will:

Pre-established Harmony:

Mind and body act in parallel, coordinated by God.

No causal interaction needed, avoiding Descartes’ problem.

Freedom within Determinism:

Monads unfold their potential based on internal principle (appetition).

Human freedom lies in acting according to reason, not randomness.

Example: A person chooses to study philosophy. The decision arises from inner nature and rational clarity, not external causation.

Critical Evaluation:

Strengths:

Avoids Cartesian dualism's interaction problem.

Allows for a rational basis of freedom, compatible with divine order.

Criticism:

Determinism still dominates; monads unfold pre-programmed paths.

Human freedom seems more like illusion of autonomy.

Among rationalists, Leibniz’s account offers the most coherent balance between metaphysical determinism and human freedom. By grounding free will in rational self-determination and internal unfolding, Leibniz preserves a form of moral responsibility while maintaining a logically ordered universe.

Q4:

(a) What do the existentialist thinkers mean by the slogan "existence precedes essence"? How is human existence related to human freedom according to them? Discuss. (10 + 10 Marks)

Ans: The slogan "existence precedes essence" is a central tenet of existentialist philosophy, famously articulated by Jean-Paul Sartre. Existentialism places emphasis on human freedom, individual choice, and responsibility. According to existentialists, human beings are not defined by any pre-existing essence or nature, but rather, they define themselves through their actions and decisions. This view sharply contrasts with essentialist philosophies that argue humans have an inherent nature or purpose.

"Existence Precedes Essence":

Meaning of the Slogan:

Essence refers to the nature or purpose of a thing, typically predetermined or assigned by external forces (e.g., God, biology).

For humans, existence comes first, meaning that we are born without a predetermined nature.

We define ourselves through choices and actions, creating our essence as we live.

Example:

An object (like a chair) is created with a specific purpose (to sit on). Its essence exists before it is created.

Humans, however, have no such predetermined essence. We are born, then through our decisions, actions, and relationships, we create our essence.

Sartre’s View:

Sartre asserts that humans are condemned to freedom—we must make choices in a world without inherent meaning.

We have the freedom to define our values, but with this freedom comes responsibility for our choices.

Human Existence and Freedom:

Freedom as a Core Aspect:

Existentialists like Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir argue that human beings are radically free to act as they choose.

Freedom is not just the absence of restraint, but a fundamental aspect of being human. It is through freedom that we can shape our own identities.

Freedom and Responsibility:

With freedom comes responsibility—to ourselves and to others.

For Sartre, when we make choices, we are also choosing for all of humanity. Thus, every action we take reflects what we believe humanity should be.

Existence as a Foundation for Freedom:

Freedom is not given; it arises from the realization that we exist first and then create our essence.

Human existence, therefore, is about creating meaning in an otherwise indifferent universe.

Example: A person who chooses to become a doctor, for instance, defines his or her essence through the decision to help others. That choice does not come from a preordained plan but is a self-created essence through freedom of will.

In existentialist thought, the idea that existence precedes essence emphasizes that humans have no preordained purpose. We exist, and through our choices, we define our nature. Human freedom is inseparable from this notion, as it allows individuals to create their own essence, responsibility, and meaning in life, all while acknowledging the burden that this freedom brings.

(b) Why does Husserl think that essences exhibit a kind of continuity between consciousness and being? Discuss. (15 Marks)

Ans: Edmund Husserl, the founder of phenomenology, sought to understand how consciousness interacts with the world. He argued that essences are fundamental structures of experience that reveal the deep connections between consciousness and the being of the objects we experience. Husserl’s idea of phenomenological essences transcends mere physical properties, focusing instead on the intentional nature of consciousness.

Husserl’s Notion of Essences:

Essences as Universal Structures:

For Husserl, essences are not contingent properties or individual facts, but rather universal features that can be abstracted from the specific instances of experience.

These essences are accessible through phenomenological analysis, which involves reflecting on how objects are given to consciousness.

Intentionality of Consciousness:

Husserl’s intentionality suggests that consciousness is always directed towards something. Every act of consciousness is about something, whether a physical object, an event, or even a concept.

This intentionality creates a connection between the subjective experience (consciousness) and the objective world (being), because what is experienced is always given as something meaningful to the subject.

Continuity Between Consciousness and Being:

Essences show continuity by revealing how consciousness structures its experiences. For example, the essence of a tree includes its appearance, its meaning, and how it is intended or perceived in consciousness.

In this sense, the objective world is not separate from consciousness but is constituted by the subject. Consciousness brings out the essence of objects through acts of perception, interpretation, and reflection.

Example: When we look at a tree, we don’t just see raw sensory data (color, shape), but also its meaning as a tree. This meaning is constituted by consciousness, and the essence of the tree emerges from this relationship between the mind and the world.

Critical Discussion:

Strengths of Husserl’s View:

Husserl’s focus on intentionality offers a deeper understanding of how the mind interacts with the world, highlighting the active role of consciousness in constituting the world of experience.

By analyzing essences, phenomenology reveals how objects are not just passively observed but actively constituted by the structures of consciousness.

Criticisms:

Some critics argue that Husserl’s approach may over-emphasize the role of the subject, potentially undermining the reality of the external world.

There is also debate about whether essences can be truly universal or whether they are always shaped by particular cultural or subjective conditions.

Husserl’s philosophy connects consciousness and being through the concept of essences, which provide the structural continuity between the world of objects and our experiences of them. Consciousness actively constitutes the essence of objects through acts of intentionality, revealing a deep relationship between the subjective and objective realms of experience.

(c) Explain the nature of the two dogmas that Quine refers to in his paper 'Two Dogmas of Empiricism'. (15 Marks)

Ans: In his famous essay “Two Dogmas of Empiricism” (1951), philosopher Willard Van Orman Quine critiques two central assumptions of logical positivism: the analytic-synthetic distinction and the reductionist program. Quine argues that these dogmas—fundamental to the empiricist tradition—are flawed and undermine the coherence of the empiricist approach to knowledge.

The Two Dogmas:

The Analytic-Synthetic Distinction:

Analytic statements are true by definition (e.g., "All bachelors are unmarried"), while synthetic statements require empirical verification (e.g., "The cat is on the mat").

Logical positivists argue that knowledge can be divided into these two categories: analytic knowledge is a priori, while synthetic knowledge is a posteriori.

Quine’s Critique of the Analytic-Synthetic Distinction:

Quine challenges the idea that there is a clear boundary between analytic and synthetic statements. He argues that meaning cannot be entirely separated from experience—there are no statements whose meaning is independent of empirical content.

For Quine, even seemingly analytic statements depend on empirical facts for their validation.

Example: “All bachelors are unmarried” seems analytic, but its truth depends on empirical knowledge of what “bachelor” means in the world.

The Reductionist Program:

Logical positivists hold that all knowledge can be reduced to sense-data or direct empirical observation, thereby grounding knowledge in a set of basic experiences.

Quine rejects this view, arguing that our knowledge is theory-laden and cannot be reduced to isolated observations. Instead, all knowledge is part of a web of beliefs, with no sharp distinction between basic, observational data and more complex, theoretical claims.

Quine’s Holism:

Quine advocates for holism, where statements are not isolated but interrelated, and the meaning of a statement can only be understood in the context of a theory as a whole.

Example: Even seemingly empirical statements like “The cat is on the mat” are interconnected with other beliefs and are subject to revision based on further experiences.

Critical Evaluation:

Strengths of Quine’s Argument:

Quine’s critique significantly challenges the rigidity of the analytic-synthetic distinction and offers a more flexible and holistic view of knowledge.

His rejection of reductionism forces a reconsideration of how empirical knowledge is constructed.

Criticisms:

Some philosophers argue that Quine’s holism leads to relativism, where no statement can be considered objectively true.

Critics also point out that some level of analyticity might still be useful in making sense of language and logic.

Quine’s critique of the two dogmas challenges key assumptions of logical positivism, advocating for a more interconnected and empirical approach to knowledge. His rejection of the analytic-synthetic distinction and the reductionist program reshapes how we think about empirical knowledge and its relationship to theory and language.

|

27 videos|168 docs

|

FAQs on UPSC Mains Answer PYQ 2024: Philosophy Paper 1 (Section- A) - Philosophy Optional for UPSC

| 1. What is the significance of Philosophy Paper 1 in the UPSC Mains examination? |  |

| 2. How can candidates effectively prepare for the Philosophy Paper 1 in the UPSC Mains? |  |

| 3. What are some common philosophical topics covered in Paper 1 of the UPSC Mains? |  |

| 4. How is the Philosophy Paper 1 structured in the UPSC Mains exam? |  |

| 5. What strategies can candidates use to score well in Philosophy Paper 1? |  |