UPSC Mains Answer PYQ 2024: Philosophy Paper 1 (Section- B) | Philosophy Optional for UPSC PDF Download

SECTION B

Q5: Answer the following questions in about 150 words each: (10 × 5 = 50 Marks)

(a) Do you think Cārvāka's philosophy is positivistic in nature? Give reasons and justifications for your answer.

Ans: Cārvāka philosophy, also known as Lokāyata, is one of the earliest materialistic schools of Indian thought. It rejects metaphysics, denies the authority of the Vedas, and accepts direct perception (pratyakṣa) as the only valid source of knowledge. Positivism, as developed in the West by thinkers like Auguste Comte, emphasizes empirical observation and scientific methodology. This answer explores whether Cārvāka’s approach aligns with positivistic principles.

Main Points:

Empiricism and Rejection of Inference:

Cārvākas uphold only perception (pratyakṣa) as a valid pramāṇa (means of knowledge).

They reject inference (anumāna) as unreliable due to the possibility of error.

This aligns with the positivist tendency to accept only observable, empirical evidence.

Denial of Transcendental Entities:

Cārvākas deny the existence of soul, afterlife, karma, and mokṣa—all unobservable entities.

This matches positivist rejection of metaphysical speculation beyond empirical verification.

Rejection of Vedic Authority:

Cārvāka dismisses the validity of scriptures and rituals based on unverifiable claims.

Positivists similarly reject dogmatic or scriptural authority not rooted in observable data.

Materialism and Sensory World:

Cārvāka holds that consciousness is a byproduct of the body (like intoxication from wine).

This reflects the materialistic and scientific worldview typical of positivism.

Ethics Based on Sensual Pleasure:

Cārvāka promotes enjoyment of life based on available experience, denying higher moral truths.

This practical and this-worldly focus is similar to utilitarian and positivist approaches.

Examples & Theories:

The theory of materialism found in Cārvāka resembles Comte’s Positivism, which emphasizes physical phenomena over metaphysical or theological explanations.

Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya, in his work "Lokayata: A Study in Ancient Indian Materialism," argues that Cārvāka philosophy is an early form of scientific rationalism.

Yes, Cārvāka’s philosophy can be considered positivistic in nature due to its exclusive reliance on perception, rejection of metaphysics, and focus on the material world. Though not systematically developed like modern positivism, its core principles reflect an empirical and rationalist approach to knowledge.

(b) Explain the six reasons offered by the Naiyāyikas to prove the existence of the self.

Ans: The Nyāya school of Indian philosophy aims at logical and epistemological clarity. To establish the existence of the ātman (self), Naiyāyikas present six key arguments. These are based on experiential and logical grounds that point toward the presence of a conscious agent behind mental functions.

Main Points (Six Reasons):

Desire (Icchā):

Desires such as wanting food or happiness imply a conscious experiencer.

There must be a subject who holds and experiences these desires.

Aversion (Dveṣa):

Similarly, aversion or dislike presupposes a subject who experiences it.

The self is the entity that feels such emotional tendencies.

Volition (Prayatna):

The act of will or effort, such as moving a hand, shows intentionality.

A volitional agent is required to explain such purposeful actions.

Pleasure and Pain (Sukha-Duḥkha):

Experiences of happiness and sorrow are personal and subjective.

This points to a self that undergoes these emotional states.

Cognition (Jñāna):

Awareness or knowledge cannot exist independently.

Cognition needs a substratum—the self—as its locus.

Memory (Smṛti):

Memory presupposes continuity of an experiencer over time.

The ability to recall past experiences implies an enduring self.

Example & Theories:

The Nyāya Sūtras by Akṣapāda Gautama discuss these proofs in detail.

Udayana, a later Naiyāyika, used these to argue against Buddhists who denied a permanent self.

The Naiyāyikas establish the existence of the self through six experiential and logical phenomena, each requiring a conscious subject. This cumulative reasoning forms a strong epistemic basis for the existence of ātman in Nyāya philosophy.

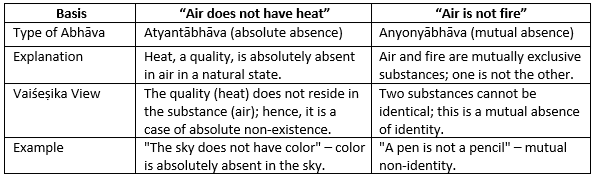

(c) Do these two sentences "Air does not have heat" and "Air is not fire" refer to the same type of absence or abhāva, according to the Vaiśeșikas? Discuss.

Ans: The Vaiśeṣika school classifies abhāva (absence or non-existence) into four types: prāgabhāva (prior absence), pradhvaṃsābhāva (posterior absence), atyantābhāva (absolute absence), and anyonyābhāva (mutual absence). The two statements in question reflect absence, but are of different types according to Vaiśeṣika analysis.

Comparison in Tabular Form:

Theory and Scholar:

Praśastapāda, in his Padārtha-dharma-saṅgraha, explains the four types of abhāva with examples.

This classification allows Vaiśeṣikas to deal with negation systematically in logic and ontology.

According to Vaiśeṣika philosophy, the sentence "Air does not have heat" exemplifies atyantābhāva (absolute absence), while "Air is not fire" represents anyonyābhāva (mutual absence). Though both express negation, the nature and basis of the absence differ, highlighting the sophistication of Vaiśeṣika logic.

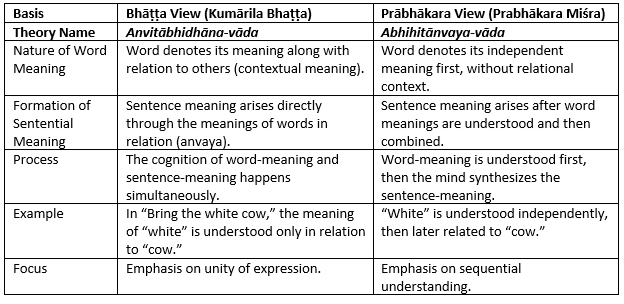

(d) How does Bhāțta's view of nature of word-meaning and sentential-meaning differ from Prābhākara's view? Critically discuss.

Ans: The Mīmāṁsā school of Indian philosophy, which is concerned with the interpretation of the Vedas, has two major sub-schools: Bhāṭṭa (founded by Kumārila Bhaṭṭa) and Prābhākara (founded by Prabhākara Miśra). Both schools developed sophisticated theories on śābdabodha (verbal cognition), focusing on how words and sentences convey meaning. Their primary differences lie in the role of individual word meanings and their integration into sentential meaning.

Difference between Bhāṭṭa and Prābhākara on Word-Meaning and Sentential-Meaning

Critical Discussion:

Bhāṭṭa's model is more aligned with how we naturally perceive meaning in conversational contexts, where relational understanding is immediate.

Prābhākara’s approach, though more analytic, suggests a step-wise comprehension process, which might not reflect actual cognition speed but allows philosophical clarity.

Critics of Prābhākara argue that isolating word meanings may distort the contextual flow of sentences.

On the other hand, Bhāṭṭa's model is sometimes seen as oversimplifying the process of individual word comprehension.

Theory & Scholar Reference:

Kumārila Bhaṭṭa’s Ślokavārttika and Prabhākara’s Bṛhatī are key texts.

Harold G. Coward, in his analysis of Indian hermeneutics, argues that the debate reflects deeper metaphysical commitments to unity (Bhāṭṭa) vs process (Prābhākara).

The Bhāṭṭa and Prābhākara schools offer distinct perspectives on word and sentence meaning. While Bhāṭṭa emphasizes immediate contextual understanding, Prābhākara stresses the logical sequence from individual words to sentence meaning. Both theories are valuable for linguistic philosophy, though Bhāṭṭa’s approach is generally seen as more practical in real-world linguistic applications.

(e) "In Viśiștādvaita philosophy, the relationship between God and the world is parallel to that between an individual self and its body." Critically discuss.

Ans: Viśiṣṭādvaita Vedānta, as expounded by Rāmānuja, is a non-dualistic philosophy that accepts qualified monism. It proposes that Brahman (God) is the only reality, but is qualified by attributes (cit and acit – sentient and non-sentient beings). One of the key metaphors used by Rāmānuja is the body-soul relationship to explain the connection between God and the world.

Main Points:

Śarīra-Śarīrī Bhāva (Body-Soul Relationship):

Just as the body is controlled and sustained by the soul, the world (jagat) and souls (jīvas) are the body of Brahman.

Brahman is the indwelling controller (antaryāmin) and the ultimate substratum of all reality.

Cit and Acit as Attributes:

Cit (souls) and acit (matter) are real, distinct, but inseparable from Brahman.

They do not exist independently but qualify Brahman, like attributes qualify a substance.

Unity with Diversity:

The analogy preserves unity (only Brahman exists ultimately) and diversity (souls and matter have distinct roles).

This differs from Advaita, which sees multiplicity as illusion (māyā), and from Dvaita, which sees duality as permanent.

Scriptural Basis:

Rāmānuja interprets Upaniṣadic statements such as “sarvaṁ khalvidaṁ brahma” to mean that all is Brahman with qualifications.

Example:

Just as a person acts through the body, God operates through the world and individual selves.

Liberation (mokṣa) involves realizing one’s inseparable dependence on Brahman, not merging or remaining apart.

Critical Evaluation:

The analogy is effective in showing a non-dualistic yet inclusive view of reality.

Critics argue that retaining multiplicity challenges the claim of pure non-duality.

However, Rāmānuja successfully navigates between absolute monism and strict dualism.

Theoretical Reference:

Rāmānuja’s Śrī Bhāṣya elaborates this body-soul analogy.

Scholars like John Carman highlight how this framework supports religious devotion (bhakti) with a metaphysical basis.

The Viśiṣṭādvaita view of the God-world relationship, modeled after the body-soul analogy, beautifully integrates unity and plurality. It affirms Brahman as the all-encompassing reality while preserving the individuality of souls and matter. This balanced metaphysical vision supports a devotional and realistic engagement with the world.

Q6:

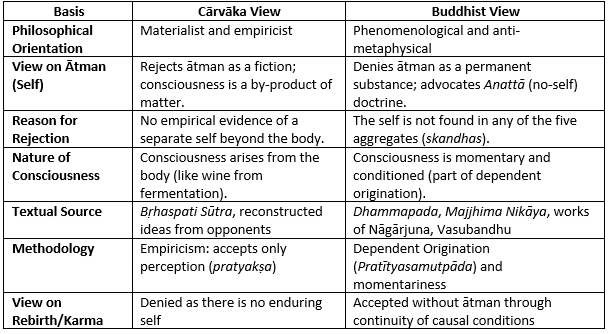

(a) Differentiate between the Cārvākas' refutation of self as a transcendental category and the Buddhist rejection of ātmā. (20 Marks)

Ans: Both Cārvākas and Buddhists reject the existence of a permanent, transcendental self (ātman), but they do so from entirely different philosophical premises. While Cārvākas approach it from a materialist and empirical perspective, the Buddhists reject it on phenomenological and metaphysical grounds. Their refutations reflect deep contrasts in ontology and epistemology.

Comparison:

Example:

Cārvāka: “When the body dies, the person ceases to exist. There's no observer beyond the senses.”

Buddhism: “What we call a person is a bundle of aggregates (skandhas), none of which is a self.”

Theory and Scholars:

Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya sees Cārvāka as a proto-scientific rejection of metaphysics.

Nāgārjuna, in Mūlamadhyamakakārikā, elaborates on the illusion of the self through śūnyatā (emptiness).

Cārvākas reject ātman due to lack of perception and materialist logic, while Buddhists reject it as a metaphysical fiction inconsistent with experiential reality. Both positions deny a transcendental self, but their motivations and implications are fundamentally different—empirical versus phenomenological, material versus momentary.

(b) How do the two schools of Buddhism arrive at two opposed conclusions, namely "everything is void" and "everything is real" from the same doctrine of Pratityasamutpāda? Answer with arguments. (15 Marks)

Ans: The doctrine of Pratītyasamutpāda or dependent origination is central to all Buddhist schools. It holds that all phenomena arise in dependence upon causes and conditions. However, two major schools—Madhyamaka and Yogācāra—interpret this doctrine differently, leading to contrasting conclusions: śūnyatā (emptiness) in Madhyamaka and vijñaptimātra (idealism) in Yogācāra.

Main Points:

Common Ground – Pratītyasamutpāda:

Both schools agree that nothing arises independently; everything is conditioned.

This refutes essentialist views of a permanent self or substance.

Madhyamaka School – Nāgārjuna:

Interprets dependent origination as implying emptiness (śūnyatā).

Since everything is dependent, nothing has inherent existence (svabhāva).

Hence, everything is void of self-nature.

Mūlamadhyamakakārikā states: “That which is dependently arisen, we call empty.”

Yogācāra School – Asaṅga and Vasubandhu:

Emphasizes the mind-only (vijñaptimātra) doctrine.

External objects are projections of consciousness.

Since everything arises in dependence on the mind, consciousness is real.

Thus, everything is real as mental constructs—not void, but cittamātra.

Opposing Conclusions:

Madhyamaka: Emptiness is the ultimate truth—leads to transcendence of all conceptual constructs.

Yogācāra: Consciousness is the ultimate reality—aims at purifying cognition.

Critical Analysis:

The contradiction is only apparent, not real.

Both schools aim at the cessation of suffering but through different metaphysical strategies.

One negates duality through emptiness, the other through idealist monism.

Though both Madhyamaka and Yogācāra derive from the same doctrine of dependent origination, they arrive at divergent ontological views. One sees dependent arising as proof of emptiness; the other sees it as evidence of mind-dependence and reality. This divergence highlights Buddhism’s rich interpretative traditions grounded in a shared foundation.

(c) What is the distinction between Bhāvabandha and Dravyabandha, according to the Jainas? Discuss. (15 Marks)

Ans: In Jain philosophy, bandha (bondage) refers to the process by which karmic matter binds to the jīva (soul). Jainism categorizes this bondage into Dravyabandha (physical bondage) and Bhāvabandha (psychic or emotional bondage). Both are interrelated but distinct in nature and function.

Distinction between Dravyabandha and Bhāvabandha

Examples:

Bhāvabandha: A person feels jealousy (passion), which causes vibrations in the soul.

Dravyabandha: These vibrations attract and bind karmic pudgala (particles) to the soul.

Theory and Scholars:

Detailed in Tattvārthasūtra by Umāsvāti, particularly in chapters 8 and 9.

Jain texts stress the importance of controlling passions to prevent Bhāvabandha.

Bhāvabandha and Dravyabandha are sequential yet interconnected aspects of karmic bondage in Jainism. While Bhāvabandha refers to the inner psychological cause, Dravyabandha denotes its external material effect. Liberation in Jainism begins with the transformation of bhāva (inner state) to prevent the influx and binding of karmic matter.

Q7:

(a) Present an account of evolution of Prakrti as propounded in Sāṃkhyakārikā. In this context, also explain the difference between buddhi, mahat and ahaṃkāra. (10 + 10 Marks)

Ans: Sāṃkhya philosophy, one of the six orthodox systems of Indian thought, is known for its dualistic metaphysics involving Puruṣa (consciousness) and Prakṛti (primordial matter). The Sāṃkhyakārikā of Īśvarakṛṣṇa systematically explains the evolution of the universe from Prakṛti without divine intervention. The process is a rational and ordered emergence of 23 tattvas (principles) from Prakṛti.

Evolution of Prakṛti:

Prakṛti (Primordial Nature):

Prakṛti is unmanifest, eternal, and composed of three guṇas: sattva, rajas, and tamas.

Evolution starts when there is proximity with Puruṣa, causing disturbance in equilibrium of guṇas.

First Evolution – Mahat (Intellect):

The first product of Prakṛti.

Represents cosmic intelligence or determinative faculty.

Associated with virtue, wisdom, and discrimination (viveka).

Second Evolution – Ahaṃkāra (Ego):

Emerges from Mahat.

Ahaṃkāra is the principle of individuality or self-sense.

It divides into three types: sāttvika (mind), rājasa (organs), tāmasa (elements).

From Ahaṃkāra Emerge:

Manas (Mind) – from sāttvika ahaṃkāra.

Five Jñānendriyas (sense organs).

Five Karmendriyas (motor organs).

Five Tanmātras (subtle elements).

Five Mahābhūtas (gross elements).

Difference between Mahat, Buddhi and Ahaṃkāra:

Theoretical Reference:

Sāṃkhyakārikā, verses 22–27 detail the process of evolution.

Commentator Gaudapāda explains the interrelationship between these tattvas.

The evolution of Prakṛti in the Sāṃkhyakārikā is a logical, non-theistic unfolding of the cosmos. Mahat, buddhi, and ahaṃkāra represent successive stages of inner evolution—from cosmic intelligence to individual identity—forming the basis of psychological and material phenomena.

(b) "So long as there are changes and modifications in citta, the self is reflected therein, and, in the absence of discriminative knowledge, identifies itself with them." Present an appraisal of Yoga Soteriology in the light of the above statement. (15 Marks)

Ans: This statement is central to Patañjali's Yoga philosophy, highlighting the misidentification of Puruṣa (pure consciousness) with citta-vṛttis (modifications of the mind). The goal of Yoga is kaivalya (liberation)—the realization of Puruṣa's distinctness from Prakṛti, achieved by halting mental fluctuations.

Key Points of Yoga Soteriology:

Citta and Its Modifications:

Citta comprises buddhi, ahaṃkāra, and manas.

It constantly undergoes vṛttis (thought-patterns), creating reflections of the self.

In ignorance, Puruṣa appears to identify with these reflections.

Avidyā (Ignorance):

The root cause of bondage is avidyā—not knowing the distinction between Puruṣa and citta.

This leads to asmitā (egoism), rāga (attachment), dveṣa (aversion), and abhiniveśa (fear of death).

Role of Discriminative Knowledge (Viveka-khyāti):

True liberation arises when one realizes the difference between seer (Puruṣa) and seen (Prakṛti).

This is known as viveka-khyāti or discriminative knowledge.

Then, the self ceases to identify with changing mental states.

Cessation of Modifications – Yogasūtra 1.2:

“Yogaḥ citta-vṛtti-nirodhaḥ” – Yoga is the cessation of modifications in citta.

When vṛttis stop, the self rests in its true nature.

Liberation (Kaivalya):

Not annihilation, but isolation of Puruṣa from Prakṛti.

Leads to eternal, uncontaminated awareness.

Examples:

Like a mirror reflecting images, citta reflects the self.

Liberation is like cleansing the mirror, so it stops displaying distortions.

Yoga soteriology views bondage as a misidentification caused by mental modifications. Through discipline and knowledge, one isolates Puruṣa from the fluctuations of citta, achieving liberation. This framework places emphasis not on suppression but on clarity of discrimination—an inner awakening to one's true, unchanging nature.

(c) "Our Yoga is a double movement of ascent and descent." Discuss the above statement in the context of Sri Aurobindo's conception of Integral Yoga. (15 Marks)

Ans: Sri Aurobindo’s Integral Yoga is a unique spiritual path combining classical Indian yoga with modern evolutionist philosophy. The statement refers to the dual process of ascending consciousness to the Divine (ascent) and bringing down divine consciousness into worldly life (descent). Unlike traditional Yoga, which seeks mokṣa through withdrawal, Integral Yoga aims for divinization of life.

Double Movement of Integral Yoga:

Ascent – Rising to the Supramental Plane:

The aspirant rises from the ego-bound physical, vital, and mental planes to the supermind (supramental consciousness).

It involves psychic transformation and spiritual awakening.

This ascent mirrors traditional yogic liberation.

Descent – Divine Influx into Lower Planes:

After ascending, the yogin must bring down the supramental light into the lower nature (body, life, mind).

This is not renunciation but transformation of human nature.

Integration of All Faculties:

Sri Aurobindo does not negate life but seeks to spiritualize it.

This includes integrating karma (action), jñāna (knowledge), and bhakti (devotion).

Goal – Life Divine:

Final aim is not just liberation (mokṣa) but divinization of the earth.

“All life is Yoga” – every aspect of being is a field of transformation.

Examples:

In traditional yoga, a yogi may retreat to the Himalayas.

In Integral Yoga, a seeker may remain in society and work, while engaging in spiritual transformation.

Scholarly References:

In The Life Divine, Aurobindo writes: “Man is a transitional being; he is not final.”

He advocates for the evolution of consciousness through both individual and collective effort.

Sri Aurobindo’s Integral Yoga is revolutionary in its vision of total transformation. The ascent to the Divine and the descent of the Divine into life form a cyclical, dynamic process. The purpose is not escape from the world, but its spiritual transfiguration—a synthesis of spirit and matter, inner and outer, liberation and perfection.

Q8:

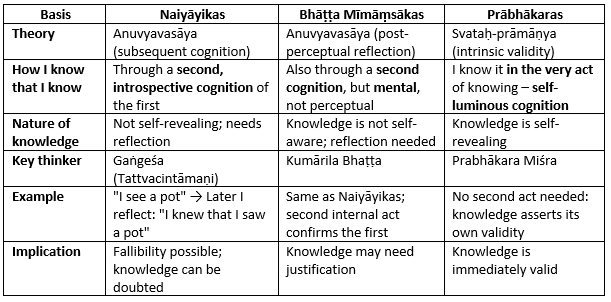

(a) How do I know that I know? Answer this question with reference to the Naiyāyikas, the Bhāțta Mīmāṃsākas and the Prābhākaras. (20 Marks)

Ans: The question "How do I know that I know?" pertains to the epistemological theory of self-awareness or knowledge of knowledge (Jñātatā or Anuvyavasāya). Classical Indian philosophical schools have offered different responses, especially the Naiyāyikas, Bhāṭṭa Mīmāṃsākas, and Prābhākaras. Their views differ in whether self-awareness is intrinsic or requires a second act of cognition.

Comparison of Views:

Theoretical Positions:

Naiyāyika View:

First act: Vyavasāya (e.g., perception of a pot).

Second act: Anuvyavasāya – introspective cognition that verifies the first.

It is extrinsic (parataḥ-prāmāṇya): knowledge is known to be true only upon further reflection.

Bhāṭṭa Mīmāṃsā View:

Accepts anuvyavasāya, but without depending on sensory faculties.

Mental recognition provides the awareness: “I know that I knew.”

Prābhākara View:

Rejects the need for any second cognition.

Believes knowledge is self-validating (svataḥ-prāmāṇya) and self-luminous.

Like light illuminating itself and others, knowledge knows itself.

Example:

Suppose one sees smoke on a hill:

Naiyāyika: First perceives smoke; then recalls and reflects, "I saw smoke, therefore fire must be there."

Bhāṭṭa: Mentally recollects that he saw smoke and draws inference.

Prābhākara: The very perception of smoke implies certainty; no reflection needed.

Each school answers the epistemic question of self-awareness differently. Naiyāyikas and Bhāṭṭas endorse a reflective second cognition (anuvyavasāya), while Prābhākaras insist that knowledge is inherently self-revealing. These distinctions show the richness of Indian epistemology in addressing meta-cognition and the nature of certainty.

(b) "A candidate who is never seen to be studying during the day time secures a high position in a competitive exam." How would the Bhāțta Mīmāmsākas and the Naiyāyikas explain the success of this candidate? Discuss. (15 Marks)

Ans: The scenario involves inference (anumāna) from negative observation: despite absence of visible effort, a person succeeds. This raises the epistemic question: Can knowledge be derived from absence? The Bhāṭṭa Mīmāṃsākas and Naiyāyikas provide different frameworks for explaining such phenomena through perception, inference, and non-perception (anupalabdhi).

Bhāṭṭa Mīmāṃsā Explanation:

Accepts Anupalabdhi as an Independent Pramāṇa:

The Bhāṭṭas accept non-perception (anupalabdhi) as a distinct and independent source of knowledge.

They would say: "I have not seen the candidate study during the day, hence I infer he must study at some other time (e.g., night)."

Postulates Hidden Causes:

They argue that the non-observation of a cause does not deny its existence.

The person may have studied at night or used other techniques like meditation, previous knowledge, etc.

Involves Līṅga (Inferential Sign):

The success is a positive result (effect), and from that the cause is inferred.

Naiyāyika Explanation:

Reject Anupalabdhi as Independent Pramāṇa:

Naiyāyikas treat absence (abhāva) as object of perception, not an independent pramāṇa.

They say: “I perceived the absence of study during the day, but perception does not deny other unobserved possibilities.”

Inference (anumāna):

From the effect (success), they infer an unseen cause.

Their logic: Wherever there is exam success, there is study; this person succeeded, so he must have studied.

Instrumental in Postulating Hidden Causal Conditions:

They might invoke the samavāya (inherence) relationship between knowledge and effort.

Even if unseen, the causal substratum (sāmānya lakṣaṇa) must exist.

Both schools agree that non-visibility of action does not imply absence of cause. The Bhāṭṭas explain it through non-perception and inference, while Naiyāyikas explain it through perception of absence and inferential postulation. In both, the key is indirect knowledge from observable effects.

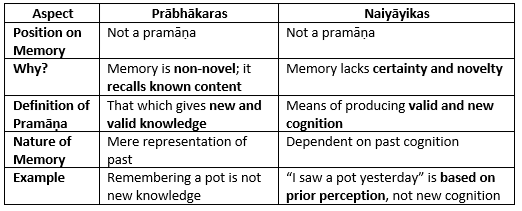

(c) On what grounds do the Prābhākaras and the Naiyāyikas reject memory as a source of knowledge? Discuss. (15 Marks)

Ans:

Memory (smṛti) is the mental recollection of past experiences. While some Indian philosophical schools recognize it as valid knowledge (pramā), others like the Naiyāyikas and Prābhākaras reject memory as a pramāṇa, arguing that it does not produce new or original knowledge.

Grounds for Rejection

Detailed Arguments:

Prābhākara View:

Memory is Not a Pramāṇa:

Only direct cognition (pratyakṣa, anumāna, etc.) yields valid knowledge.

Memory does not generate new knowledge, it recycles previous cognition.

Truth-Content is Derivative:

It depends on whether the original perception was valid.

No independent status.

Naiyāyika View:

Memory is Post-Perceptual:

It is a mental operation recalling prior knowledge.

It cannot create certainty, as doubt or error can creep in.

Validity Depends on Source:

If the prior knowledge was invalid, the memory is invalid.

Hence, not a reliable independent source.

Both Prābhākaras and Naiyāyikas reject memory as a pramāṇa because it lacks novelty and independence. For them, valid knowledge must be fresh, immediate, and verifiable. Memory, being derivative and retrospective, cannot stand as a standalone means of acquiring truth.

|

60 videos|168 docs

|

FAQs on UPSC Mains Answer PYQ 2024: Philosophy Paper 1 (Section- B) - Philosophy Optional for UPSC

| 1. What are the key topics covered in Philosophy Paper 1 for UPSC Mains? |  |

| 2. How should candidates prepare for the Philosophy Paper 1 in the UPSC Mains exam? |  |

| 3. What is the importance of ethics in Philosophy Paper 1? |  |

| 4. Are there any specific philosophers or texts that candidates should focus on for this exam? |  |

| 5. How is the Philosophy Paper 1 evaluated in the UPSC Mains exam? |  |