The Colonial Era in India NCERT Solutions | Social Science Class 8 - New NCERT PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Page No. 83 |

|

| Page No. 87 |

|

| Page No. 92 |

|

| Page No. 98 |

|

| Page No. 100 |

|

| Page No. 102 |

|

| Page No. 104 |

|

| Page No. 105 |

|

| Page No. 107 |

|

| Page No. 108 |

|

| Page No. 112 |

|

| Page No. 114 |

|

Page No. 83

The Big Questions

Q1: What is colonialism?

Ans: Colonialism means one country ruling another to use its land, people, and resources for its own benefit. It often causes hardship for the people being ruled and changes their way of life.

Q2: What drew European powers to India?

Ans: Europeans came to India mainly for trade and profit. India was famous for spices, silk, cotton, and indigo, which were in great demand in Europe. They wanted to find direct sea routes to avoid Arab traders who charged high prices. Religious motives also played a role, as the Portuguese wanted to spread Christianity. Gradually, countries like Portugal, the Netherlands, France, and Britain competed to control Indian trade and power.

Q3: What was India’s economic and geopolitical standing before and during the colonial period?

Ans:

Before the Colonial Era: India was made up of many kingdoms such as the Mughals, Marathas, Rajputs, and southern rulers. These kingdoms were rich in trade, art, and culture. India was famous for its gems, textiles, and spices, which attracted traders from Europe, Arabia, and Southeast Asia. Indian rulers made their own decisions, signed treaties, and spread Indian culture, religion, and knowledge to other parts of Asia.

During the Colonial Period: The British changed India’s economy to suit their needs. India was made to supply raw materials like cotton and indigo to Britain and to buy British goods. Local industries and crafts declined. The British controlled India’s defence, trade, and foreign affairs, and Indian soldiers were used to fight for British interests.

Q4: How did the British colonial domination of India impact the country?

Ans:

- The British drained India’s wealth and used its natural resources for their own profit.

- Traditional Indian industries such as textiles and handicrafts were destroyed because cheap British goods flooded the markets.

- Farmers suffered due to heavy land taxes under systems like the Permanent Settlement, which caused debt, poverty, and many famines.

- India lost its political freedom as the British took control of administration, defence, and foreign affairs.

- English education created a small educated class but ignored Indian knowledge, culture, and languages.

- Railways, roads, and telegraph lines were built mainly to serve British trade and military needs.

- Although these developments later helped in India’s unity and freedom movement, they were originally made to strengthen British control.

Page No. 87

Let’s Explore

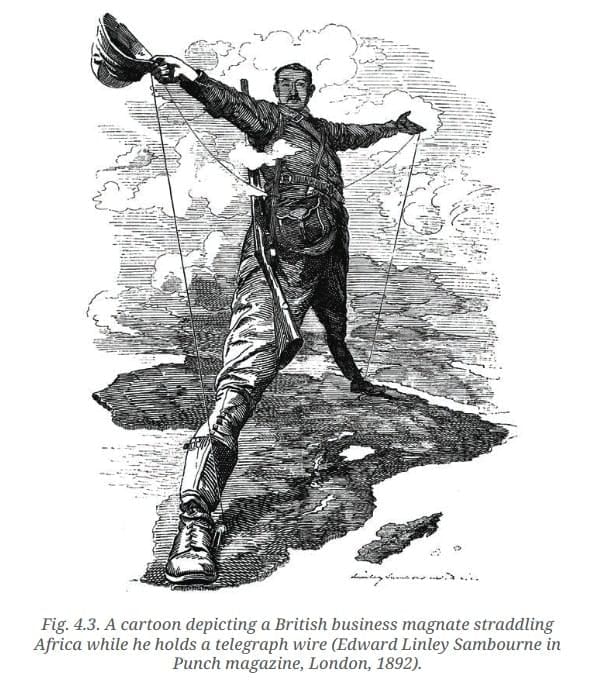

Q1: What do you think the cartoon (Fig. 4.3) is trying to express? (Keep in mind that the telegraph, which permitted instant communications for the first time, was then a recent invention.) Analyse different elements of the drawing. Ans:

Ans:

- Before the telegraph, messages took weeks or months to travel between countries.

- The telegraph made communication very fast, and people were amazed that messages could now be sent “faster than the wind.”

- The cartoon may show a person in London sending a message and someone in India receiving it instantly.

- It shows how the telegraph connected far-away parts of the world and made the Earth seem smaller.

- For the British, the telegraph helped them control their colonies easily by sending orders quickly from London to India.

Page No. 92

Let us Explore

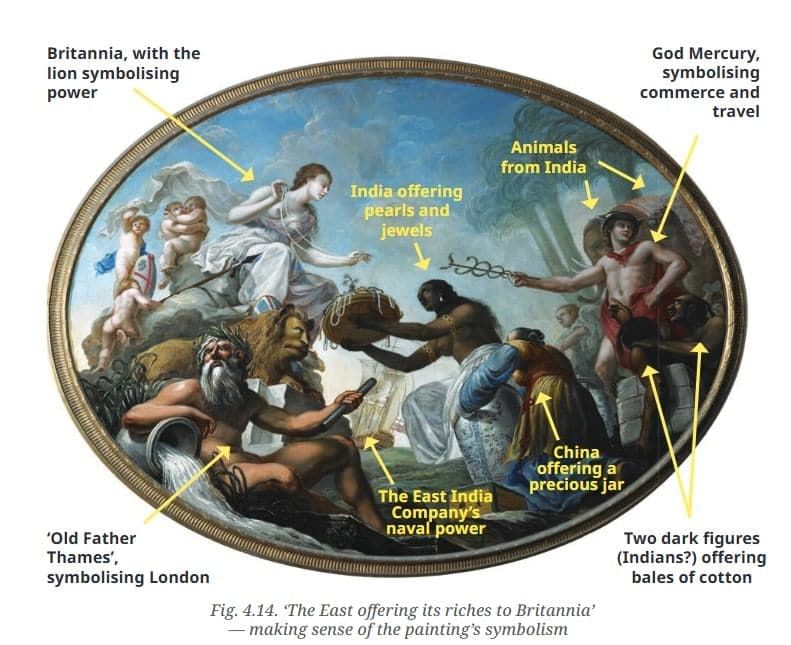

Q1: Before you read further, have a good look at the painting on the first page of this chapter. It was specially ordered for the London headquarters of the East India Company and is over three metres long. Observe every aspect of it the people in it, the objects, the symbols and the attitudes. Form groups of four or five students and let each group present its conclusions as regards the messages the painting conveys. (You will find our answers a few pages down, when we return to the painting, but avoid looking at them right now!)

Ans:

- The painting shows Britain as powerful and supreme. At the top, a white woman named Britannia is seated like a goddess, symbolising Britain’s strength and control.

- India is shown offering its wealth. Dark-skinned figures, representing Indians, are bowing and giving pearls, jewels, and cotton to the British.

- A figure from China is also seen offering gifts, showing that other countries too were giving their wealth to Britain.

- Exotic animals and trade symbols are shown to represent India’s riches and Britain’s global trade power.

- A man with a trident symbolises the British navy, which controlled the seas and trade routes.

- Another figure, called Old Father Thames, represents the River Thames in London, showing that all wealth was flowing to Britain.

Conclusion: The painting clearly shows that Britain, through the East India Company, ruled over India and other colonies and took their riches to make itself powerful.

Page No. 98

Let's Explore

Q1: Why do you think Dadabhai Naoroji means by ‘un-British rule in India’? (Hint: he was an MP in the House of Commons in 1892.)

Ans: Dadabhai Naoroji used the phrase “Un- British Rule in India” to highlight how British colonial governance violated the very principles of justice, fairness, and liberalism that Britain claim to up hold. He argued that while British rule appeared civil and progressive on the surface, it was fundamentally exploitative and unjust in practice. As a British MP, he believed the British were not treating Indians with the same respect or rights given to people in Britain.

Think About It

Q2: Let us return to this painting (Fig. 4.14), but now with some clues to its symbolism. Note how Britannia (a symbolic figure for Britain) sits higher than the colonies, pointing to her superior power; contrast with the lower position and bent posture of the colonies. Did they really ‘offer’ their wealth? Or did Britain seize it by force or ruse? Note also the Indians’ dark complexion (in contrast with that of Britannia), reflecting the belief in the superiority of white people over the dark-skinned ‘natives’.

Ans: No, Indians did not offer their wealth willingly. In most cases, Britain seized it by force, unfair laws, or oppression. The British used high taxes, unfair trade rules, and military power to take control of land, resources, and money. Indian farmers, artisans, and rulers often had no choice but to give up their wealth. So, it was not a gift it was taken through exploitation and control.

Page No. 100

Let's Explore

Q1: Do you understand all the terms used above to list and describe Indian textiles? If not, form groups of four or five and try to find out more, then compare your findings with the help of your teacher.

Ans: Here are some terms used to describe Indian textiles listed below with their simplest explanation:

- Cotton: Cotton is a soft, fluffy fiber that grows around the seeds of cotton plant. It is used to make light and breathable clothes.

- Silk: Silk is a fine and luxurious fabric that is commonly used to make saree, salwar suits, and kurtas, etc.

- Wool: Wool is a soft, warm fiber taken from the fleece (hair) of animals like sheep, it is highly used during winters to make sweaters, shawls, mufflers, etc.

- Jute: Jute is a rough yet very strong fiber; used to make sacks, ropes, carpets, and mats.

- Hemp: Hemp is a very strong natural fiber. It is used to make bags and ropes.

- Coir: Coir is a dried fiber taken from the outer husk of coconuts.

- Muslin: Muslin is a fine cotton; famous in Dhaka (Bangladesh) was used for royal garments and now is used to make regular wear cotton clothes.

Page No. 102

Think About It

Q1: What exactly did Macaulay mean when he wrote that “a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia”? And why should he want to make Indians “English in taste, in opinions, in morals, and in intellect”? How does this relate to the ‘civilising mission’ mentioned at the start of the chapter? Ask your teacher to guide a class debate on these questions.

Ans: Macaulay believed European books were superior to all Indian and Arabic books. This reveals his colonial mindset, which looked down on Indian culture and knowledge. He wanted Indians to adopt British ways of thinking, living, and believing so they would support British rule more easily. This attitude relates directly to the “civilising mission” where the British claimed to educate and improve Indians, but in reality, aimed to control and weaken Indian identity and culture.

Page No. 104

Think About It

Q1: What is meant by “the sun never sets on the British Empire”? Do you think this was a correct statement?

Ans: “The sun never sets on the British Empire” means the empire was so vast, with colonies across the world, that the sun was always shining on at least one of its lands. Yes, I think this was a true statement for that time, because Britain ruled over many countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, and the Americas.

Page No. 105

Let's Explore

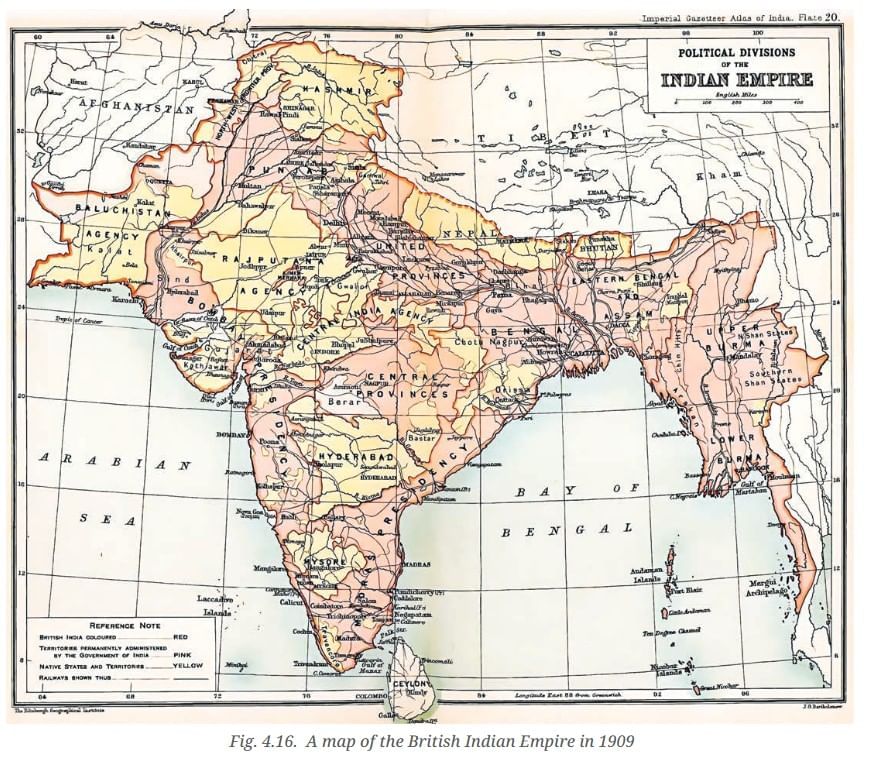

Q1: Examine the map. What are the main differences with the map of today’s India, in terms both of borders and of names? Ans:

Ans:

- The 1909 map of the Indian Empire was very different from the map of India today.

- During British rule, India included the areas of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Myanmar (Burma), which are now separate countries.

- The northwestern border also included Baluchistan and the North-West Frontier Province, which are now in Pakistan.

- Many cities have new names now — Calcutta is Kolkata, Bombay is Mumbai, and Madras is Chennai.

- During British rule, regions were called Provinces, Agencies, or Native States, but today India is divided into states and union territories.

- In the 1909 map, pink areas showed regions directly under British control, while yellow areas were princely states ruled by Indian kings under British supervision.

- The map also showed railway lines built by the British to help in trade and control over India.

Page No. 107

Let's Explore

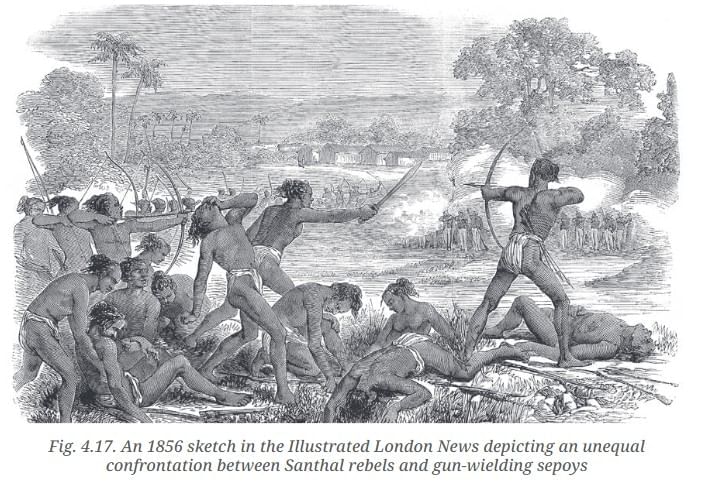

Q1: Note how the Santhals are depicted in the 1856 sketch (Fig. 4.17) drawn from an artist’s imagination: observe their complexion, dress, weapons and draw your conclusions as regards the image this depiction would create in the popular mind in Britain.

Ans: In this 1856 sketch, the Santhals are shown with dark skinned, minimal clothing, with traditional bows and arrows. They appear wild, primitive, and violent, fighting British soldiers with their handmade traditional weapons. This image, drawn from imagination, likely created a negative and fearful picture in the British public’s mind depicting the Santhals as uncivilized savages rather than people resisting injustice. It helped justify British rule as a “civilizing mission”, hiding the real reasons for tribal uprisings like exploitation and land loss.

Page No. 108

Let's Explore

Q1: Indigo is a natural deep blue pigment used in dyeing. Can you think of other natural substances that have been traditionally used in India to dye cloth?

Ans: India has used several natural substances that have been traditionally used in India to dye cloth such as Turmeric, Henna (Mehndi), Madder root, Pomegranate rind, Indigo, Neem leaves, Bark of trees, Lac insect resin etc. and these substances give various colours like yellow, reddish-brown, red, pink, greenish, gray, purple etc. These dyes were eco-friendly and used in traditional textile arts like Block Printing, Kalamkari, and Bandhani.

Q2: Why do you think was the term ‘Sepoy Mutiny’ rejected after Indian Independence? Write one paragraph explaining your reasons.

Ans: The term ‘Sepoy Mutiny’ was rejected by historians after Indian Independence because it gives the false idea that only a few Indian soldiers rebelled for personal or military reasons. In reality, the Revolt of 1857 was a large and widespread uprising involving not just Indian soldiers, but also farmers, landlords, regional kings, and citizens from different parts of India. It was a united fight against British rule and oppression. Calling it just a “mutiny” hides its true national character and the freedom struggle it represented.

Page No. 112

Let's Explore

Q1: In the sentence “It opened (or re-opened) India to the world and the world to India”, why do you think we added ‘reopened’?

Ans: The term “re-opened” is used because India was already connected to the world through trade, culture, and philosophy long before colonialism. India was a key player in the Silk Route and had established seaports and trade systems exporting spices, gems, cotton, indigo, and more. Buddhism and Hinduism spread widely across Asia before British arrival. Thus, the British did not open India to the world for the first time; they reconnected it to global systems through their colonial networks.

Q2: Some argue that stolen cultural heritage has been better preserved abroad than it would have been in India. What is your view on its repatriation? Discuss in groups.

Ans: Many people believe that the stolen art and cultural treasures of India should be returned to their homeland. These objects are part of our history, identity, and pride. Keeping them in foreign museums ignores the injustice of how they were taken. Today, India has the ability to preserve and display them properly in its own museums. If brought back, these treasures would inspire Indians and remind us of our rich cultural heritage instead of being kept far away in other countries.

Page No. 114

Questions and Activities

Q1: What is colonialism? Give three different definitions based on the chapter or your knowledge.

Ans: Colonialism means when a powerful country takes control over another country and uses its land, people, and resources for its own benefit. It affects the political, economic, and cultural life of the country being ruled.

Three definitions of colonialism are:

- Historical Definition: Colonialism is when a foreign power controls another land and uses its wealth for its own interests.

- Political Definition: Colonialism is the rule of one country over another, removing local rulers and freedom.

- Economic and Social Definition: Colonialism is when a strong nation exploits the economy and people of a weaker country and forces its own language, education, and culture on them.

Q2: Colonial rulers often claimed that their mission was to ‘civilise’ the people they ruled. Based on the evidence in this chapter, do you think this was true in the case of India? Why or why not?

Ans: No, the British claim of “civilising” India was not true. They said they came to improve India through modern education, law, and railways, but their real aim was to gain political control and economic benefit.

Evidence from the chapter shows:

- Economic exploitation: India’s raw materials like cotton and indigo were taken to support British industries, while Indian crafts and textile industries were destroyed.

- High taxes and famines: Heavy land taxes made farmers poor, and during famines the British kept collecting revenue instead of giving help.

- Loss of Indian rule: Many Indian rulers were defeated or forced into unfair treaties.

- Biased education: English education was promoted to create Indians who thought like the British.

Thus, the so-called “civilising mission” was only a way to justify exploitation and British domination in India.

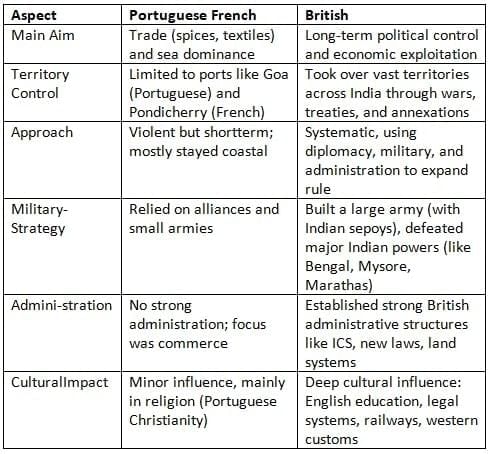

Q3: How was the British approach to colonising India different from earlier European powers like the Portuguese or the French?

Ans: The British approach to colonising India was more systematic, organised, and long-lasting compared to the earlier European powers like the Portuguese and the French, who were mainly focused on trade and coastal control.

Key Differences:

The British went beyond trading they built an empire, interfered in Indian politics, introduced new systems, and completely reshaped India’s economy and society. In contrast, the Portuguese and French were mainly commercial powers with limited political ambitions and smaller territorial countries.

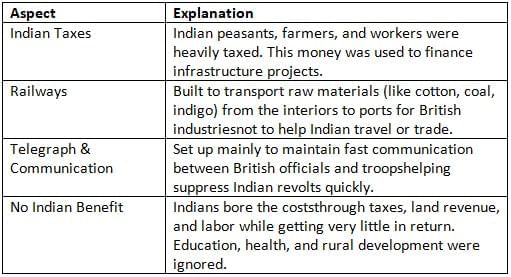

Q4: “Indians funded their subjugation.” What does this mean in the context of British infrastructure projects in India like the railway and telegraph networks?

Ans: During colonial rule, the British introduced major infrastructure projects such as the railway, telegraph, and postal networks. While these appeared modern and progressive, their main purpose was to serve British interests, not the welfare of Indians.

How Indians ‘Funded their own subjugation’:

Conclusion: The infrastructure may have modernized India physically, but it was funded by Indians to strengthen British economic and military control. So, Indians unknowingly paid in the form of heavy taxes and natural resources in India, for the very tools used to dominate and exploit them.

Conclusion: The infrastructure may have modernized India physically, but it was funded by Indians to strengthen British economic and military control. So, Indians unknowingly paid in the form of heavy taxes and natural resources in India, for the very tools used to dominate and exploit them.

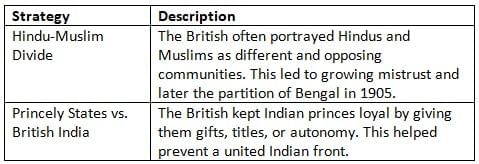

Q5: What does the phrase ‘divide and rule’ mean? Give examples of how this was used by the British in India?

Ans: “Divide and Rule” refers to a strategy used by the British to maintain their control over India by creating or deepening divisions among Indians especially on the basis of religion, caste, region, and class so that Indians would not unite against British rule.

Examples of “Divide and Rule” Policy in India:

Conclusion: The British mastered the art of “Divide and Rule”, using religious, social, and political differences among Indians to keep them weak and disunited making it easier for a small foreign power to rule a vast country.

Conclusion: The British mastered the art of “Divide and Rule”, using religious, social, and political differences among Indians to keep them weak and disunited making it easier for a small foreign power to rule a vast country.

Q6: Choose one area of Indian life, such as agriculture, education, trade, or village life. How was it affected by colonial rule? Can you find any signs of those changes still with us today? Express your ideas through a short essay, a poem, a drawing, or a painting.

Ans: Colonialism and Indian Agriculture: Under British rule, Indian agriculture changed completely, but not for the benefit of farmers. The British forced farmers to grow cash crops like indigo, cotton, and opium, which were needed by British industries instead of food crops for Indians. The Permanent Settlement of 1793 made zamindars collect land taxes, which caused the exploitation of peasants and led to poverty and debt. Many farmers suffered during frequent famines, while grains were exported to Britain. Railways were built mainly to carry raw materials to ports, not to help farmers. Even today, problems like farmer debts, unequal land ownership, and focus on cash crops can be traced back to colonial agricultural policies.

Q7: Imagine you are a reporter in 1857. Write a brief news report on Rani Lakshmibai’s resistance at Jhansi. Include a timeline or storyboard showing how the rebellion began, spread, and ended, highlighting key events and leaders.

Ans:

The Jhansi Flame: Rani Lakshmibai’s Heroic Resistance!

Date: June 1858

Reporter: Vansh Mishra The Hindustan Herald

Rani Lakshmibai, the brave queen of Jhansi, became a symbol of courage during the Revolt of 1857. When the British tried to take over Jhansi under the Doctrine of Lapse, denying her adopted son Damodar Rao the throne, she refused to give up and declared, “I shall not surrender my Jhansi!”

She led her soldiers, including women, with great bravery against the British. After fierce battles, Jhansi was captured in April 1858, but Rani escaped and joined Tatya Tope at Gwalior. She fought her final battle fearlessly and was martyred on 17 June 1858. Her leadership and sacrifice continue to inspire Indians even today.

Timeline / Storyboard: Rani Lakshmibai and the 1857 Revolt

1853: After the death of Raja Gangadhar Rao, the British annexed Jhansi under the Doctrine of Lapse. Rani Lakshmibai protested against this unfair decision but her appeal was ignored.

May 1857: The great Revolt of 1857 began in Meerut and soon spread to many parts of North India. Inspired by this uprising, Rani Lakshmibai decided to protect her kingdom from British rule.

June 1857: The people and soldiers of Jhansi joined the rebellion. Rani Lakshmibai took command of her army and began preparing to defend her state with courage and determination.

March 1858: The British army, led by Sir Hugh Rose, attacked Jhansi. Rani Lakshmibai fought bravely and organised a strong defence, inspiring even women to join the battle.

April 1858: After days of heavy fighting, Jhansi was captured by the British. However, Rani Lakshmibai escaped with her loyal soldiers and continued the struggle.

June 1858: She joined forces with Tatya Tope at Gwalior and fought her final battle against the British. On 17 June 1858, Rani Lakshmibai was martyred while fighting bravely for her country’s freedom.

Q8: Imagine an alternate history where India was never colonised by European powers. Write a short story of about 300 words exploring how India might have developed on its path.

Ans:

Title: The Lotus Never Wilted

In an alternate history, the European powers never reached India. The country continued to grow under strong kingdoms like the Marathas, Rajputs, Mysore, and the Sikhs, who later formed a Bharatiya Sabha to promote peace, trade, and cooperation. India developed its own industries in textiles, metalwork, and shipbuilding through trade with countries like Japan and China.

Great universities such as Takshashila and Nalanda were rebuilt, where ancient learning was combined with modern science. Indian languages, art, and culture flourished freely without foreign control.

By 1900, India became a global centre for knowledge, science, and Ayurveda. The caste system grew weaker as reformers promoted equality and education for all. In 1947, India proudly led the World Congress of Civilizations, showing unity and progress. The tricolour flag symbolised not freedom from rule, but India’s strength, diversity, and self-reliance. The lotus of India bloomed peacefully, untouched by foreign rule.

Q9: Role-play: Enact a historical discussion between a British official and an Indian personality like Dadabhai Naoroji on the British colonial rule in India.

Ans: A Historical Role-Play Dialogue:

Setting: London, late 1890s — after a debate in the British Parliament.

British Official: Mr. Naoroji, your “Drain of Wealth” idea seems exaggerated. The British have built railways, schools, and laws in India. Don’t you think these are benefits?

Dadabhai Naoroji: Sir, I agree that railways and schools were built, but they were made with Indian money and for British use. India’s wealth is being drained to Britain through unfair trade and taxes.

British Official: But India is part of the Empire. These developments would not have happened without British rule.

Naoroji: Progress cannot come from exploitation. Railways were built to take raw materials to British factories, not to help Indians. Our industries are destroyed, and people suffer from poverty and famine.

British Official: That is how empires work, Mr. Naoroji.

Naoroji: Then let justice begin with self-rule. India is capable of governing itself. We want fairness, dignity, and freedom — not charity.

Q10: Explore a local resistance movement (tribal, peasant, or princely) from your state or region during the colonial period. Prepare a report or poster describing:

- What was the specific trigger, if any?

- Who led the movement?

- What were their demands?

- How did the British respond?

- How is this event remembered today (e.g., local festivals, songs, monuments)?

Ans:

Report: The Santhal Rebellion (1855-56)

Region: Present-day Jharkhand (then part of Bengal Presidency)

Tribal Group: Santhals

Trigger:

The Santhals were badly exploited by zamindars, moneylenders, and British officials. Heavy taxes, loss of land, and constant debt forced them into poverty and suffering.

Beginning of the Revolt:

In June 1855, in the village of Bhognadih, leaders Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu, along with their brothers Chand and Bhairav, raised the flag of revolt. Over 60,000 Santhals joined them, declaring they would not pay taxes or follow British laws.

Demands and Actions:

They demanded an end to zamindari oppression, return of tribal land, and justice for their people. The rebels attacked British offices and moneylenders using bows, arrows, and traditional weapons.

British Response:

The British crushed the rebellion with brutal force. Thousands were killed, and the leaders were captured and executed.

Legacy:

The Santhal Rebellion became the first major tribal uprising against British rule. June 30 is celebrated as Hul Diwas (Day of Revolt). Statues of Sidhu and Kanhu Murmu stand in Dumka and Ranchi, and the Santhal Hul Museum keeps their memory alive.

|

31 videos|128 docs|7 tests

|

FAQs on The Colonial Era in India NCERT Solutions - Social Science Class 8 - New NCERT

| 1. What were the main motivations behind the British colonization of India? |  |

| 2. How did the British East India Company establish control over India? |  |

| 3. What were some significant social changes in India during the colonial era? |  |

| 4. How did the Indian Rebellion of 1857 impact British policies in India? |  |

| 5. What role did economic exploitation play in the colonial rule of India? |  |