Class 9 History Chapter 4 Question Answers - Forest Society and Colonialism

Q.1. Discuss the rise of commercial forestry under the colonial governments.

Ans.

- British Concern for Forest Preservation: The British recognized the vital role of forests in shipbuilding and railway construction but feared local exploitation and reckless logging by traders could lead to forest destruction.

- Appointment of Dietrich Brandis: Seeking solutions, the British appointed German forestry expert Dietrich Brandis as the first Inspector General of Forests in India.

- Introduction of Scientific Forestry: Brandis advocated for a systematic forest management system, including legal regulations to restrict tree felling and grazing to preserve forests for timber production.

Establishment of Indian Forest Service and Forest Research Institute: In 1864, Brandis established the Indian Forest Service and contributed to formulating the Indian Forest Act of 1865. The Imperial Forest Research Institute was founded in Dehradun in 1906 to promote research and education in forestry.

Criticism of Scientific Forestry: The practice of scientific forestry, characterized by replacing diverse natural forests with monoculture plantations, has drawn criticism from ecologists and others who question its scientific basis and ecological impact.

Q.2. How did the new forest laws affect the forest dwellers?

Ans. Divergent Perspectives on Forest Management:

- Foresters and villagers held contrasting views on the ideal forest composition.

- Villagers preferred forests with diverse species to meet various needs like fuel, fodder, and leaves.

- The forest department prioritized trees suitable for shipbuilding and railway construction, such as teak and sal, resulting in the promotion of specific species while others were cut down.

Impact of New Forest Laws:

- The implementation of new forest laws caused significant hardship for villagers nationwide.

- Everyday practices like woodcutting for housing, grazing cattle, collecting fruits, roots, hunting, and fishing became illegal under the Forest Act.

Consequences for Villagers:

- Villagers resorted to stealing wood from forests due to the prohibition on their customary activities.

- Those caught faced extortion by forest guards, leading to increased vulnerability and exploitation.

- Women collecting fuel wood faced heightened concerns and uncertainties due to the legal restrictions.

Harassment by Authorities:

- Police constables and forest guards often harassed villagers, demanding free food as bribes.

- This abuse of power further exacerbated the challenges faced by local communities, deepening their mistrust and resentment towards forest authorities.

Q.3. “The introduction of extremely exploitatives and oppressive policies proved to be a disaster.” With reference to Bastar

(a) What were these policies?

(b) What were the consequences of these policies?

Ans. (a)

Colonial Government's Forest Reservation Proposal:

- In 1905, the colonial government proposed reserving two-thirds of the forest area, aiming to cease shifting cultivation, hunting, and forest produce collection.

Concerns of the People of Bastar:

- Residents of Bastar expressed deep concern over the government's proposal.

- Some villages were permitted to remain within reserved forests under the condition of providing free labor for tree cutting, transportation, and forest protection, leading to the establishment of forest villages.

Displacement and Discontent:

- Many villages faced displacement without prior notice or compensation due to the forest reservation policy.

- Villagers had long endured increased land rents and demands for unpaid labor and goods from colonial officials.

- The devastating famines of 1899-1900 and 1907-1908 compounded the villagers' hardships.

Impact of Reservations:

- The forest reservations acted as the final blow, exacerbating the already dire situation for the villagers.

(b)

Emergence of Dissent and Discussion:

- People began gathering in village councils, marketplaces, and festivals to discuss grievances and issues related to forest reservation.

- The initiative originated from the Dhruvas of the Kanger forest, where the first reservation occurred.

Role of Gunda Dhur and the Rebellion Movement:

- Gunda Dhur from village Nethanar emerged as a significant figure in the 1910 movement.

- Messages circulated between villages, symbolized by mango boughs, earth clumps, chillies, and arrows, inviting villagers to rebel against British rule.

- Villages contributed to rebellion expenses, leading to looting of markets, burning and robbing of officials' houses, schools, and police stations, and redistribution of grain.

British Response and Suppression:

- British authorities deployed troops to suppress the rebellion.

- Despite attempts at negotiation by Adivasi leaders, the British surrounded their camps and opened fire.

- Troops marched through villages, punishing participants with floggings and other penalties.

Outcome of the Rebellion:

- The rebellion lasted for three months before British forces regained control.

- Gunda Dhur evaded capture, symbolizing a victory for the rebels.

- As a result, work on forest reservation was temporarily halted, and the reserved area was reduced to its pre-1910 planned size.

Q.4. How did the transformation in the forest management during the colonial period affect the following?

(a) Pastoral communities

(b) Shifting cultivators

Ans. During the colonial period, the British recognized the strategic importance of Indian forests for shipbuilding and the rapid expansion of railway networks. However, they were concerned about uncontrolled local use of forests and excessive logging by traders, which they believed would lead to the destruction of forest resources.

To address these concerns, the British government appointed Dietrich Brandis, a German forest expert, as the first Inspector General of Forests in India. He advocated for the implementation of a scientific forest management system and the training of officials in conservation science.

As part of this new policy:

- Strict regulations were introduced to control tree felling and grazing.

- Violators were punished under new forest laws.

- In 1864, the Indian Forest Service was established.

- The Indian Forest Act of 1865 was passed to provide legal backing to forest control measures.

- Later, in 1906, the Imperial Forest Research Institute was set up in Dehradun to promote forest research and professional training.

These changes had a profound impact on various forest-dependent communities:

(a) Impact on Pastoral Communities:

- Before the forest laws, pastoral and nomadic communities depended on forests for grazing and hunting animals like deer and partridge.

- After the introduction of these laws, hunting and grazing were banned, and violators were punished as poachers.

- Some communities were unjustly labelled as "criminal tribes" and were forced to work in colonial factories, mines, or plantations under strict supervision.

- These restrictions severely disrupted their traditional ways of life and economic independence.

(b) Impact on Shifting Cultivators:

- European officials viewed shifting cultivation as harmful, as it involved burning forest areas and temporarily using land for cultivation.

- They feared that the burning of forests could damage valuable timber and that land left fallow wouldn't support tree growth for railway use.

- Also, the irregular pattern of shifting cultivation made it difficult for the British to calculate taxes.

- As a result, the practice was banned, and shifting cultivators were displaced from their traditional lands.

- Some were forced to find alternative livelihoods, while others resisted these changes through small and large-scale rebellions.

Q.5. How did the following contribute towards the decline of forest cover in India between 1880-1920? (CBSE 2010)

(a) Railways and shipbuilding

(b) Commercial farming

Ans. (a) (1) Railways : The spread of railways from 1850s created a new demand. Railways were essential for successful colonial control, administration, trade and movement of troops. Thus to run locomotives, (a) wood was needed as fuel (b) and to lay railway lines as sleepers were essential to hold tracks together. As the railway tracks spread throughout India, larger and larger number of trees were felled. Forests around the railway tracks started disappearing fast.

(2) Shipbuilding : UK had the largest colonial empire in the world. Shortage of oak forests created a great timber problem for the shipbuilding of England. For the Royal Navy, large wooden boats, ships, courtyards for shipping etc., trees from Indian forests were being felled on massive scale from the 1820s or 1830s to export large quantities of timber from India. Thus the forest cover of the subcontinent declined rapidly.

(b) Commercial Farming : Large areas of natural forest were also cleared to make space for the plantations or commercial farming. Jute, rubber, indigo, tobacco etc. were the commercial crops that were planted to meet Britain’s growing need for these commodities. The British colonial government took over the forests and gave of a vast area and exported it to Europe. Large areas of forests were cleared on the hilly slopes to plant tea or coffee. This also contributed to the decline of the forest cover in India.

Q.6. How was colonial management of forests in Bastar similar to that of Java?

Ans.

- The colonial government imposed new forest laws according to which two-thirds of the forests were reserved. Shifting cultivation, hunting and collection of forest produce was banned.

- Most people in forest villages were displaced without notice or compensation.

- In the same way, when the Dutch gained control over the forests in Java, they enacted forest laws, restricting villagers' access to forests. Now wood could only be cut for specific purposes and from specific forests under close supervision.

- Villagers were punished for grazing cattle, transporting wood without a permit or travelling on forest road with horse-carts or cattle.

- Permits were issued to the villagers for entry into forests and collection of forest products.

- Both followed a system of forestry which was known as scientific forestry.

Q.7. What new trends and developments have affected the forestry of today?

OR

Discuss the new developments in forestry after the 1980s.

Ans.

- Since the 1980s, governments in Asia and Africa have acknowledged the emergence of conflicts stemming from scientific forestry practices and policies that alienate forest communities from forest areas.

- There has been a shift towards prioritizing forest conservation over timber extraction as a primary objective of forest management.

- Recognizing the importance of involving communities living near forests in conservation efforts, governments have begun to reassess their approaches.

- In many regions of India, such as Mizoram and Kerala, the preservation of dense forests owes much to the active protection by local villagers in sacred groves known by various names like sarnas, devarakudu, kau, rai, etc.

- Some villages have adopted community-based forest patrolling, with households taking turns, as an alternative to relying solely on forest guards for protection.

- Presently, local forest communities and environmentalists are exploring diverse models of forest management aimed at ensuring sustainable conservation practices.

Ans. Meaning of Shifting Cultivation:

- Shifting cultivation, also known as swidden agriculture, is a traditional farming practice prevalent in various regions of Asia, Africa, and South America.

- It is known by different local names such as lading, milpa, chitemene, tavy, and chena, among others, depending on the region.

- In India, terms like dhya, penda, bewar, nevad, jhum, podu, khandad, and kumri are used to refer to shifting cultivation.

Reasons why shifting cultivation was regarded as harmful by European foresters:

- Shifting cultivation involves cutting and burning parts of the forest in rotation, followed by sowing seeds in the ashes after the first monsoon rains, with the crop being harvested by October-November. These plots are cultivated for a few years before being left fallow for 12 to 18 years to allow the forest to regenerate.

- The practice often involves growing a mixture of crops, such as millets in central India and Africa, manioc in Brazil, and maize and beans in other parts of Latin America.

- European foresters viewed shifting cultivation as detrimental to forests, as the land used for cultivation periodically could not support the growth of trees suitable for railway timber.

- There was also a risk of forest fires spreading and damaging valuable timber when forests were burnt for cultivation.

- Additionally, the practice made it challenging for the government to assess and collect taxes effectively.

- Consequently, the colonial government imposed bans on shifting cultivation, leading to the forced displacement of many forest-dwelling communities.

- Some communities had to adapt to alternative occupations, while others resisted the bans through various forms of rebellion, both large and small.

Q.9. Where is Bastar located? Discuss its history and its people.

Ans.

- Bastar is situated in the southern part of Chhattisgarh and borders Orissa, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra. The river Indrawati flows from east to west across Bastar. The central part of Bastar is a plateau. To the north of this plateau is the Chhattisgarh plain and to its south is the Godavari plain.

- The people of Bastar believe that each village was bestowed land by the earth and hence they offer something in return during agricultural celebrations.

- Apart from the earth the people of Bastar show reverence to the spirits of rivers, forests and the mountains. Different communities such as Maria and Muria Gonds, Dhurwas, Bhatras and Halbas practise common customs and beliefs but speak different dialects. Each village is well aware of its boundaries. They look after and preserve their natural resources.

- There exists a give and take relationship among the communities. If a village wants some forest produce from another village a small price is paid before taking it. This price is called ‘dhand’ or ‘man’ or ‘devsari’.

- Villagers engage watchmen to look after their forests for a price. This price is collected from all the families.

- There is a large annual gathering — a big hunt where the headmen of all the villages in a ‘pargana’ (a group of villages) meet and discuss matters that concern them.

Q.10. Why did the people of Bastar rise in revolt against the British? Explain.

Ans. (i) In 1905, the colonial government imposed laws to reserve two-thirds of the forests, stop shifting cultivation, hunting and collection of forest produce. People of many villages were displaced without any natice or compensation.

(ii) For long, villagers had been suffering from increased land rents and frequent demands for free labour and goods by colonial officials.

(iii) The terrible famines in 1899–1900 and again in 1907–1908 made the life of people miserable. They blamed the colonial rule for their sorry plight.

(iv) The initiative of rebellion was taken by the Dhurwas of the Kanger forest, where reservation first took place. Gunda Dhur was an important leader of the rebellion.

Q.11. How forest of Java were affected by Dutch colonialists? Describe how farms for rice cultivation in Java expanded?

Ans.

- The Dutch initiated forest management in Java, Indonesia, with the primary objective of obtaining timber for shipbuilding purposes, similar to the British.

- Forest control by the Dutch began in the 18th century, culminating in their dominance over Java's forests.

- In 1770, the Kalangs rebelled against Dutch control by attacking a fort at Joana, but the rebellion was quelled by Dutch forces.

- Forest laws were enacted by the Dutch in the 19th century, limiting villagers' access to forests and imposing restrictions on woodcutting for specific purposes under strict supervision.

- Villagers faced penalties for various infractions such as grazing cattle in young forest areas, unauthorized wood transportation, or using forest roads with carts or cattle.

- Initially, the Dutch imposed rents on cultivated forest land, but later exempted some villages from these rents under the 'blandongdiensten' system, which required collective labor and buffaloes for timber cutting and transportation.

- Over time, rent exemption was replaced with small wages for forest villagers, albeit with restricted rights to cultivate forest land.

- Java transitioned into a renowned rice-producing region in Indonesia after gaining independence from colonial rule, witnessing extensive development of rice farms.

Q.12. Describe four provisions of the Forest Act of 1878.

Ans. (i) The Forest Act of 1878 divided forests into three categories : reserved, protected and village forests.

(ii) The best forests were called 'reserved forests'.

(iii) Villagers could not take anything from reserved forests, even for their own use.

(iv) For house building or fuel, they could take wood from protected or village forests.

Q.13. Explain how did the First World War and the Second World War have a major impact on forests?

Ans. The First and Second World Wars significantly affected forests in the following ways:

- In India, working plans for forests were abandoned, and the forest department extensively cut trees to fulfill British war requirements.

- The Dutch in Java adopted a 'scorched earth' policy, destroying sawmills and burning large teak logs to prevent them from being seized by the Japanese.

- The Japanese exploited forests irresponsibly for their war industries, compelling forest villagers to participate in deforestation.

- In Indonesia, many villagers took advantage of the wartime chaos to expand cultivation in the forests.

- After the wars, Indonesian authorities faced challenges in reclaiming the forest land that had been used for cultivation.

Q.14. Who was appointed as the first Inspector General of Forests in India? Explain any three reforms introduced by him.

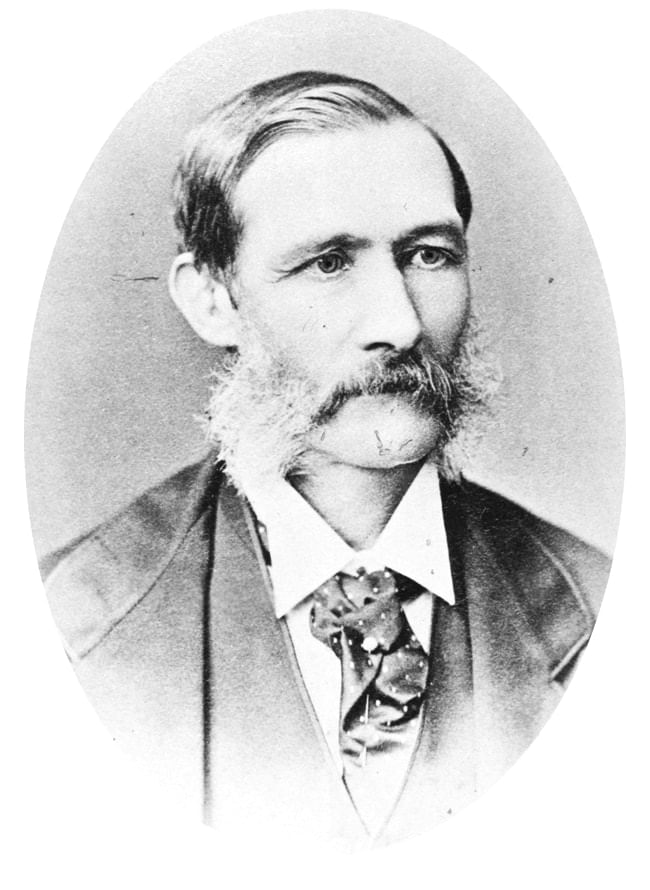

Ans. A German forest expert, Dietrich Brandis, was made the first Inspector General of Forests in India.

(i) Brandis introduced a proper system to manage the forests and people had to be trained in the science of conservation. This system needed legal sanction and so rules about the use of forests had to be framed.

(ii) Felling of trees and grazing had to be restricted so that forests could be preserved for timber production. Trespassers had to be punished.

(iii) Brandis set up the Indian Forest Service in 1864 and helped formulate the Indian Forest Act of 1865. The Imperial Forest Research Institute was set up at Dehradun in 1906. The system they taught here was called 'scientific forestry'.

Dietrich Brandis

Dietrich Brandis

Q.15. How did commercial farming led to a decline in forest cover during colonial period?

Ans.

- Commercial farming during the colonial period contributed to a decline in forest cover.

- Natural forests with diverse tree species were cleared.

- Monoculture plantations were established, where only one type of tree was planted in straight rows.

- Forest officials conducted surveys to estimate the area covered by different types of trees.

- Working plans for forest management were developed, determining the annual cutting quota for plantation areas.

- Deforested areas were replanted, but often with the same monoculture species, leading to the destruction of natural forest cover on a large scale.

Ans.

- In the Bastar region, the local people respected the spiritual significance of the natural elements, including the river, forest, and mountain.

- Each village was aware of its boundaries and took responsibility for protecting the natural resources within those boundaries.

- Villagers maintained a system where if wood was needed from another village's forest, a small fee called "devsari," "dand," or "man" was paid in exchange.

- Watchmen were hired by some villages to safeguard the forests, with each household contributing grain to compensate them for their services.

- Annually, a significant gathering known as the "big hunt" took place, where the headmen of villages within a "pargana" convened to discuss various issues, including matters related to the forests.

Ans. Deforestation witnessed a significant surge during colonial rule, characterized by systematic and extensive clearing of forests.Colonial expansion led to a rapid increase in cultivation for various purposes:

- The British administration actively promoted the cultivation of cash crops such as jute, sugar, wheat, and cotton. The heightened demand for these crops during the 19th century drove the clearing of forests to cater to Europe's requirements for both food grains and raw materials essential for industrial growth.

- The advent of railways from around 1850 brought about a new demand for timber. Wood became indispensable for fueling locomotives and as sleepers for laying railway tracks, leading to an accelerated depletion of forests.

- The railway network witnessed rapid expansion from the 1860s onwards, with approximately 25,500 km of track laid by 1890.

- Contracts were awarded by the government to individuals for timber procurement, resulting in a rapid disappearance of forests in areas surrounding railway tracks.

- Large swathes of natural forests were cleared to make way for tea, coffee, and rubber plantations, fulfilling Europe's increasing demand for these commodities.

Q.18. Why did commercial forestry become important during the British rule ?

Ans.

- Commercial forestry gained importance during British rule due to the depletion of oak forests in England by the early nineteenth century, posing a threat to timber supply for the Royal Navy.

- The construction of English ships relied heavily on a consistent provision of robust timber, critical for safeguarding and maintaining imperial power through naval strength.

- Prior to 1850, commercial forestry in India was recognized as crucial, prompted by the need to address England's timber scarcity. Exploration teams dispatched in the 1820s surveyed India's forest resources, endorsing the potential for commercial forestry.

- Subsequently, within a short span, significant deforestation occurred in India, with extensive tree felling and substantial timber exports, driven by the green signal given for commercial forestry by exploration parties.

- The advent of railways in the 1850s further fueled demand for wood. The colonial government in India recognized railways as indispensable for effective internal administration, colonial trade facilitation, and swift movement of imperial troops, necessitating wood for locomotive fuel and sleepers for track stability.

|

55 videos|637 docs|79 tests

|

FAQs on Class 9 History Chapter 4 Question Answers - Forest Society and Colonialism

| 1. What impact did colonialism have on forest societies? |  |

| 2. How did forest societies resist colonial exploitation? |  |

| 3. What role did forests play in the identity of indigenous communities during colonial times? |  |

| 4. How did colonial policies affect biodiversity in forest regions? |  |

| 5. In what ways can the history of forest societies inform current conservation efforts? |  |