Water Pollution Control by Adsorption | Environmental Engineering - Civil Engineering (CE) PDF Download

ADSORPTION

- Adsorption can be simply defined as the concentration of a solute, which may be molecules in a gas stream or a dissolved or suspended substance in a liquid stream, on the surface of a solid.

- In an adsorption process, molecules or atoms or ions in a gas or liquid diffuse to the surface of a solid, where they bond with the solid surface or are held there by weak intermolecular forces. The adsorbed solute is called the adsorbate, and the solid material is the adsorbent.

- Activated clays, activated carbons, fuller earths, bauxite, alumina, bone char, molecular sieves, synthetic polymeric adsorbents, silica gel, etc. are the main types of adsorbents used in the industry.

- There are basically two types of adsorption processes: one is physical adsorption (physisorption) and the second is chemisorption.

DIFFUSION OF ADSORBATE

There are essentially four stages in the adsorption of an organic/inorganic species by a porous adsorbent:

1. Transport of adsorbate from the bulk of the solution to the exterior film surrounding the adsorbent particle;

2. Movement of adsorbate across the external liquid film to the external surface sites on the adsorbent particle (film diffusion);

3. Migration of adsorbate within the pores of the adsorbent by intraparticle diffusion (pore diffusion);

4. Adsorption of adsorbate at internal surface sites.

All these processes play a role in the overall sorption within the pores of the adsorbent. In a rapidly stirred, well mixed batch adsorption, mass transport from the bulk solution to the external surface of the adsorbent is usually fast. Therefore, the resistance for the transport of the adsorbate from the bulk of the solution to the exterior film surrounding the adsorbent may be small and can be neglected. In addition, the adsorption of adsorbate at surface sites (step 4) is usually very rapid and thus offering negligible resistance in comparison to other steps, i.e. steps 2 and 3. Thus, these processes usually are not considered to be the rate-limiting steps in the sorption process.

In most cases, steps (2) and (3) may control the sorption phenomena.

For the remaining two steps in the overall adsorbate transport, three distinct cases may occur:

Case I: external transport > internal transport.

Case II: external transport < internal transport.

Case III: external transport ≈ internal transp ort.

In cases I and II, the rate is governed by film and pore diffusion, respectively. In case III, the transport of ions to the boundary may not be possible at a significant rate, thereby, leading to the formation of a liquid film with a concentration gradient surrounding the adsorbent particles.

Usually, external transport is the rate-limiting step in systems which have (a) poor phase mixing, (b) dilute concentration of adsorbate, (c) small particle size, and (d) high affinity of the adsorbate for the adsorbent. In contrast, the intra-particle step limits the overall transfer for those systems that have (a) a high concentration of adsorbate, (b) a good phase mixing, (c) large particle size of the adsorbents, and (d) low affinity of the adsorbate for adsorbent . The possibility of intra-particle diffusion can be explored using the intra-particle diffusion model .

(3.12.1)

Where, qt is th e amount of the adsorbate adsorbed on the adsorbent (mg/g) at any t and is the intra-particle diffusion rate constant, and values of I give an idea about the thickness of the boundary layer. In order to check whether surface diffusion controls the adsorption process, the kinetic data can be analyzed using Boyd kinetic expression which is given by:

(3.12.2)

Where, F(t) = qt /qe is the fractional attainment of equilibrium at time t, and Bt is a mathematical function of F. However, if the data exhibit multi-linear plots, then two or more steps influence the overall adsorption process. In general, external mass transfer is characterized by the initial solute uptake and can be calculated from the slope of plot between C/Co versus time. The slope of these plots can be calculated either by assuming polynomial relation between C/Co and time or it can be calculated based on the assumption that the relationship was linear for the first initial rapid phase.

ADSORPTION KINETIC

Pseudo-first-order and pseudo-second-order model: The adsorption of adsorbate from solution to adsorbent can be considered as a reversible process with equilibrium being established between the solution and the adsorbate. Assuming a non-dissociating molecular adsorption of adsorbate molecules on adsorbent, the sorption phenomenon can be described as the diffusion controlled process. Using first order kinetics it can be shown that with no adsorbate initially present on the adsorbent, the uptake of the adsorbate by the adsorbent at any instant t is given as .

(3.12.3 )

where, qe is the amount of the adsorbate adsorbed on the adsorbent under equilibrium condition, kf is the pseudo-first order rate constant. The pseudo-second-order model is represented as :

(3.12.4)

The initial sorption rate, h (mg/g min), at t -> 0 is defined as

(3.12.5)

ADSORPTION ISOTHERM

Equilibrium adsorption equations are required in the design of an adsorption system and their subsequent optimization . Therefore it is important to establish the most appropriate correlation for the equilibrium isotherm curves have discussed the theory associated with the most commonly used isotherm models. Various isotherms namely Freundlich, Langmuir, Redlich-Peterson (R-P) and Tempkin which are given in following table are widely used to fit the experimental data:

Table 3.12.2. Various isotherm equations for the adsorption process

KR: R–P isotherm constant (l/g), aR: R–P isotherm constant (l/mg), β: Exponent which lies between 0 and 1, Ce: Equilibrium liquid phase concentration (mg/l), KF: Freundlich constant (l/mg), 1/n: Heterogeneity factor, KL: Langmuir adsorption constant (l/mg), qm: adsorption capacity (mg/g), KT: Equilibrium binding constant (l/mol), BT: Heat of adsorption.

The Freundlich isotherm is derived by assuming a heterogeneous surface with a nonuniform distribution of heat of adsorption over the surface, whereas in the Langmuir theory the basic assumption is that the sorption takes place at specific homogeneous sites within the adsorbent. The R-P isotherm incorporates three parameters and can be applied either in homogenous or heterogeneous systems. Tempkin isotherm assumes that the heat of adsorption of all the molecules in the layer decreases linearly with coverage due to adsorbent-adsorbate interactions, and the adsorption is characterized by a uniform distribution of binding energies, up to some maximum binding energy.

FACTORS CONTROLLING ADSORPTION

The amount of adsorbate adsorbed by an adsorbent from adsorbate solution is influenced by a number of factors as discussed below:

Nature of Adsorbent

The physico-chemical nature of the adsorbent is important. Adsorbents differ in their specific surface area and affinity for adsorbate. Adsorption capacity is directly proportional to the exposed surface. For the non-porous adsorbents, the adsorption capacity is inversely proportional to the particle diameter whereas for porous material it is practically independent of particle size. However, for porous substances particle size affects the rate of adsorption. For substances like granular activated carbon, the breaking of large particles to form smaller ones open up previously sealed channels making more surface accessible to adsorbent.

Pore sizes are classified in accordance with the classification adopted by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), that is, micro-pores (diameter (d) <20 Å), meso-pores (20 Å < d < 500 Å) and macro-pores (d > 500 Å). Micro-pores can be divided into ultra-micropores (d < 7 Å) and super micro-pores (7 Å < d < 20 Å).

pH of Solution

The surface charge as well as the degree of ionization is affected by the pH of the solution. Since the hydrogen and hydroxyl ions adsorbed readily on the adsorbent surface, the adsorption of other molecules and ions is affected by pH. It is a common observation that a surface adsorbs anions favorably at low pH and cations in high pH range.

Contact Time

In physical adsorption most of the adsorbate species are adsorbed within a short interval of contact time. However, strong chemical binding of adsorbate with adsorbent requires a longer contact time for the attainment of equilibrium. Available adsorption results reveal that the uptake of adsorbate species is fast at the initial stages of the contact period, and thereafter, it becomes slower near the equilibrium. In between these two stages of the uptake, the rate of adsorption is found to be nearly constant. This may be due to the fact that a large number of active surface sites are available for adsorption at initial stages and the rate of adsorption is a function of available vacant site. Concentration of available vacant sites decreases and there is repulsion between solute molecules thereby reducing the adsorption rate.

Initial Concentration of Adsorbate

A given mass of adsorbent can adsorb only a fixed amount of adsorbate. So the initial concentration of adsorbate solution is very important. The amount adsorbed decreases with increasing adsorbate concentration as the resistance to the uptake of solute from solution of adsorbate decreases with increasing solute concentration. The rate of adsorption is increased because of the increasing driving force .

Temperature

Temperature dependence of adsorption is of complex nature. Adsorption processes are generally exothermic in nature and the extent and rate of adsorption in most cases decreases with increasing temperature. This trend may be explained on the basis of rapid increase in the rate of desorption or alternatively explained on the basis of Le-Chatelier's principle. Some of the adsorption studies show increased adsorption with an increase in temperature. This increase in adsorption is mainly due to an increase in number of adsorption sites caused by breaking of some of the internal bonds near the edge of the active surface sites of the adsorbent. Also, if the adsorption process is controlled by the diffusion process (intraparticle transport-pore diffusion), than the sorption capacity increases with an increase in temperature due to endothermicity of the diffusion process. An increase in temperature results in an increased mobility of the metal ions and a decrease in the retarding forces acting on the diffusing ions. These result in the enhancement in the sorptive capacity of the adsorbents .

ADSORPTION OPERATIONS

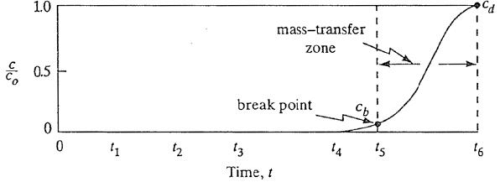

Fixed bed adsorbers

- These are used for the adsorption of dyes and colorants, refractory pollutants from wastewater.

- The size of the bed depends on the gas flow rate and the desired cycle time.

- The bed length usually varies from 0.3 to 1.3 m.

- The gas is fed downward through the adsorbent particles in the bed.

- Inside the bed, the adsorbent particles are placed on a screen, or performed plate.

- Upflow of feed is usually avoided because of the tendency of fluidization of the particles at high rates. When the adsorption reaches the desired value, the feed goes to the other bed through an automatic valve and the regeneration process starts.

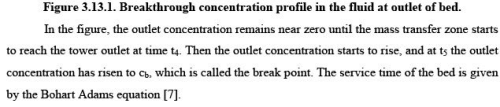

Where, t is the service time of the bed, n is the linear flow rate of the solution, X is the depth of the bed, K is the rate constant, No is the adsorption capacity, Co is the concentration of the solute entering into the bed, CB is the allowable effective concentration.

Stirred tank adsorbers

- Stirred tank adsorbers are generally used for the removing pollutants from the aqueous wastes.

- Such an adsorber consists of a cylindrical tank fitted with a stirrer or air sparger.

- The stirrer or air-sparger keeps the particles in the tank in suspension.

- The spent adsorbate is removed by sedimentation or filtration.

- The mode of operation may be batch or continuous.

Continuous adsorbers

- The solid and the fluid move through the bed counter currently and come in contact with each other throughout the entire apparatus without periodic separation of the phrases.

- The solid particles are fed from the top and flow down through the adsorption and regeneration sections b gravity and are then returned to the top of the column by an air lift or mechanical conveyer.

- Multi-stage fluidized beds, in which the fluidized solids pass through down comers from stage to stage, may be used for fine particles.

|

14 videos|142 docs|98 tests

|

FAQs on Water Pollution Control by Adsorption - Environmental Engineering - Civil Engineering (CE)

| 1. What is water pollution control by adsorption? |  |

| 2. How does adsorption help in water pollution control? |  |

| 3. What are some common adsorbent materials used for water pollution control? |  |

| 4. How is adsorption different from other water treatment methods? |  |

| 5. What are the advantages of water pollution control by adsorption? |  |