CAT Exam > CAT Questions > Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat...

Start Learning for Free

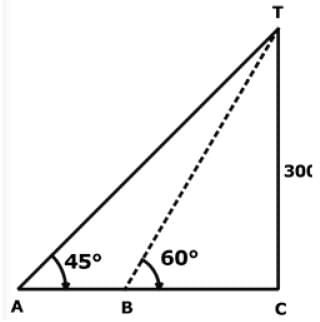

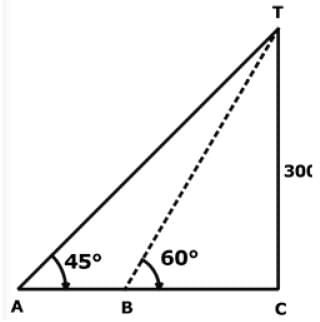

Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.

- a)100 m

- b)100√3 m

- c)50√3 m

- d)50 m

- e)100/√3 m

Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

| FREE This question is part of | Download PDF Attempt this Test |

Verified Answer

Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the fe...

Tan 60 = √3 = TC/BC

View all questions of this test

Hence, BC = 100√3 m

|

Explore Courses for CAT exam

|

|

Similar CAT Doubts

Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for CAT 2024 is part of CAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the CAT exam syllabus. Information about Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for CAT 2024 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for CAT 2024 is part of CAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the CAT exam syllabus. Information about Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for CAT 2024 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for CAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for CAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice Ranjan goes to a countryside lake for a boat ride. Standing at the ferry counter, he looked at the opposite bank and observed a tall tower on a hill downstream, the angle of elevation being 45°. Ranjan comes to know from the bystanders that the tower is a historical ruin and decides to visit it. The boat takes him directly to the opposite bank, from where the angle of elevation to the top of the tower becomes 60°. While exploring the site, he comes to know that the combined height of the tower and the hill is 300 m. If the speed of the boat by which Ranjan travelled was 2 km/hr in still waters, find the distance between the bank of the river(nearest to tower) and the tower.a) 100 mb) 100√3 mc) 50√3 md) 50 me) 100/√3 mCorrect answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice CAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for CAT exam

|

|

Suggested Free Tests

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.