SAT Exam > SAT Questions > The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 p...

Start Learning for Free

The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?

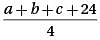

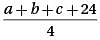

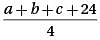

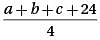

- a)

- b)

- c)m + 8

- d)

Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

Verified Answer

The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If...

Let’s call the 3 positive integers a, b, and c. If the average of these numbers is m, then

Multiply by 3: a + b + c = 3m

New average when 24 is included in the set:

Substitute a + b + c = 3m:

Multiply by 3: a + b + c = 3m

New average when 24 is included in the set:

Substitute a + b + c = 3m:

Most Upvoted Answer

The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If...

Let’s call the 3 positive integers a, b, and c. If the average of these numbers is m, then

Multiply by 3: a + b + c = 3m

New average when 24 is included in the set:

Substitute a + b + c = 3m:

Multiply by 3: a + b + c = 3m

New average when 24 is included in the set:

Substitute a + b + c = 3m:

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Similar SAT Doubts

The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?

Question Description

The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? for SAT 2025 is part of SAT preparation. The Question and answers have been prepared according to the SAT exam syllabus. Information about The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? covers all topics & solutions for SAT 2025 Exam. Find important definitions, questions, meanings, examples, exercises and tests below for The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?.

Solutions for The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? in English & in Hindi are available as part of our courses for SAT.

Download more important topics, notes, lectures and mock test series for SAT Exam by signing up for free.

Here you can find the meaning of The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? defined & explained in the simplest way possible. Besides giving the explanation of

The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer?, a detailed solution for The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? has been provided alongside types of The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? theory, EduRev gives you an

ample number of questions to practice The average (arithmetic mean) of a set of 3 positive integers is m. If the number 24 is added to this set, what is the average (arithmetic mean) of the new set of numbers?a)b)c)m + 8d)Correct answer is option 'B'. Can you explain this answer? tests, examples and also practice SAT tests.

|

Explore Courses for SAT exam

|

|

Signup for Free!

Signup to see your scores go up within 7 days! Learn & Practice with 1000+ FREE Notes, Videos & Tests.