Archaeological Sources | History Optional for UPSC (Notes) PDF Download

Archaeology

Archaeology is the study of the human past through material remains, which are objects created, modified, or used by people. These remains can range from large structures like palaces and temples to small everyday items like broken pottery. Archaeologists examine a variety of materials, including structures, artifacts, bones, seeds, pollen, seals, coins, sculptures, and inscriptions. The goal of archaeology is to recover and understand the material remains of past cultures.

Exploration and Excavation

Archaeology is a science that allows us to systematically dig through the layers of old mounds to understand the material life of past people. A mound is an elevated piece of land that covers the remains of ancient habitations. There are different types of mounds:

- Single-culture mounds: These mounds represent only one culture throughout their entire layer, such as the Painted Grey Ware (PGW) culture, Satavahana culture, or Kushan culture.

- Major-culture mounds: In these mounds, one culture is dominant while others are of secondary importance.

- Multi-culture mounds: These mounds represent several important cultures in succession, sometimes overlapping with each other.

An excavated mound helps us understand the successive layers of material and other aspects of a culture. Excavation can be done either vertically or horizontally.

- Vertical excavation: This involves digging lengthwise to uncover the period-wise sequence of cultures. It is usually confined to a part of the site and provides a good chronological sequence of material culture.

- Horizontal excavation: This entails digging the mound as a whole or a major part of it. This method may provide a complete idea of the site culture during a specific period. However, horizontal excavations are expensive and less common.

Preservation of Ancient Remains

The preservation of ancient remains varies by climate:

- In dry and arid climates like western Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, and northwestern India, antiquities are found in better states of preservation.

- In moist and humid climates such as the mid-Gangetic plains and deltaic regions, even iron implements suffer corrosion, and mud structures become difficult to detect. In these areas, burnt brick structures or stone structures are well preserved.

Excavations have revealed insights into

- The villages established around 6000 BC in Baluchistan.

- The material culture developed in the Gangetic plains during the second millennium BC.

- The layout of ancient settlements.

- The types of pottery used.

- The forms of houses.

- The kinds of cereals consumed.

- The tools and implements used.

In South India, some people buried their dead along with tools, weapons, pottery, and other belongings, encircled by large stones. These burial structures, known as megaliths, provide insights into life in the Deccan region from the Iron Age onwards.

Methods of Dating and Information Gathering

- Various methods are used to fix the dates of mounds and materials, with radiocarbon dating being the most important. Radiocarbon, or Carbon 14 (C14), is a radioactive carbon isotope present in all living objects. It decays at a uniform rate, and by measuring the loss of C14 content in an ancient object, its age can be determined. The half-life of C14 is 5,568 years, but objects older than 70,000 years cannot be dated using this method.

- The history of climate and vegetation is studied through plant residues and pollen analysis. It is suggested that agriculture was practiced in Rajasthan and Kashmir around 7000–6000 BC. The analysis of metal artifacts helps identify the mines from which metals were obtained and the stages in the development of metal technology. Examination of animal bones indicates whether animals were domesticated and their uses.

Geological and Biological Studies

Geological studies provide insights into the history of soil, rocks, and other geological aspects, while biological studies offer the history of plants and animals. Understanding the interaction between soils, plants, animals, and humans is crucial for comprehending human history. Geological and biological advances, along with archaeological remains, are important sources for studying over 98 percent of the total time scale of history, starting from the origin of the earth.

Ethno-archaeology

- Ethno-archaeology involves studying the behavior and practices of living communities to interpret archaeological evidence related to past communities. In the Indian subcontinent, many traditional features and methods survive, such as in agriculture, animal husbandry, house building, clothing, and food. Modern craftspersons provide valuable insights into ancient craft-making methods. For example, the tradition of carnelian bead manufacturing in Khambhat, Gujarat, today offers clues about how Harappan beads may have been made and the social organization of bead makers.

- Ethno-archaeology helps fill gaps in history, such as understanding women’s roles in subsistence and craft-related activities in early times. Studies of modern hunter-gatherers and shifting cultivators provide insights into the life-ways of people who followed similar subsistence strategies in the past. However, it is essential to consider the differences between present and past contexts when using ethno-archaeological evidence.

Archaeology as a Source of History

- Archaeology provides an anonymous history that sheds light on cultural processes rather than specific events. It is primarily used to study prehistory and ancient history, with archaeology being the only source for prehistory. It also serves as the only source for parts of the past covered by non-deciphered written records (Proto-history) and continues to offer valuable information even after the historical period begins.

- Unfortunately, when literary sources become available, historians often use archaeology as a secondary, corroborative source. One of the challenges in early Indian history is adequately incorporating archaeological evidence into larger historical narratives. Archaeology reveals aspects of everyday life that may not be emphasized in texts, making it a crucial source for historians.

- The ancient Indians left behind numerous material remains, such as stone temples in South India and brick monasteries in Eastern India. However, most of these remains are buried in mounds scattered across India. Archaeology provides information on the history of human settlements and specific details about modes of subsistence, including the food people procured and how they obtained it. It offers insights into the crops grown, agricultural implements used, and animals hunted and tamed. Additionally, archaeology is an excellent source of information on the history of technology, including raw materials, their sources, and methods used to make various artifacts.

- Archaeology also helps reconstruct routes and networks of exchange, trade, and interaction between communities. While many religious texts are available for ancient and early medieval India, an exclusively text-based view of religion does not provide a complete understanding of religious practice. Material evidence of ancient religions contributes significantly to this area.

- Translating archaeological cultures into history poses problems, as an archaeological culture may not correspond to a linguistic group, political unit, or social group. Understanding changes in material culture, particularly pottery traditions, remains an important question that has not been adequately addressed in ancient India.

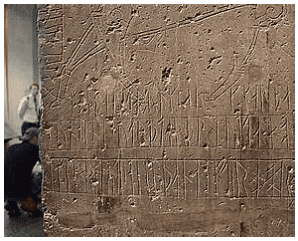

Epigraphy

- Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions, which are a significant aspect of archaeology and archaeological sources. Inscriptions were carved on various materials such as seals, stone pillars, rocks, copper plates, temple walls, wooden tablets, and bricks or images.

- In ancient India, the earliest inscriptions were recorded on stone. However, during the early centuries of the Christian era, copper plates started to be used for inscriptions. Despite this, the practice of engraving inscriptions on stone continued, especially in South India, where many inscriptions were also recorded on temple walls to serve as permanent records.

Evidences of early inscriptions

- The Harappan inscriptions, which are yet to be deciphered, appear to be written in a pictographic script where ideas and objects are represented through pictures.

- The oldest deciphered inscriptions date back to the late 4th century BCE and are written in Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts. These include inscriptions from the Maurya emperor Ashoka, which are in various languages and scripts, primarily in Prakrit language and Brahmi script (written from left to right), with some in Kharoshthi script (written from right to left).

- In the 14th century AD, two Ashokan pillar inscriptions were discovered by Firoz Shah Tughlaq in Meerut and Topra, Haryana. He brought them to Delhi for deciphering, but the pandits were unable to do so. These inscriptions were eventually deciphered in 1837 by James Prinsep, a civil servant with the East India Company in Bengal.

- Brahmi script was widely used across India, except for the north-western region, where Greek and Aramaic scripts were employed for Ashokan inscriptions. Brahmi remained the main script until the end of Gupta times.

- After the 7th century, significant regional variations in Brahmi script emerged. The relationship between the Harappan script and Brahmi or Kharoshthi remains unclear, leaving the gap in writing between these periods a mystery.

Evidences of writing

- While there is no direct mention of writing in Vedic literature, references to poetic metres, grammatical and phonetic terms, large numbers, and complex calculations in later Vedic texts suggest that writing may have been known during that time. The first definite references to writing and written documents appear in Buddhist Pali texts, particularly the Jatakas and the Vinaya Pitaka.

- Panini’s Ashtadhyayi mentions the word lipi (script). The Brahmi script seen in Ashoka’s inscriptions appears to be a developed script, implying a prior history of several centuries. Recent evidence from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka, where potsherds with short inscriptions dating to the early 4th century BCE were found, indicates that Brahmi existed in pre-Maurya times.

- Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts are considered semi-syllabic or semi-alphabetic, lying between alphabetic and syllabic scripts.

Kharoshthi scripts

- Kharoshthi was primarily used in the north-west, particularly in Gandhara. Ashoka’s Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra inscriptions are in this script.

- Kharoshthi was later used in north India under the Indo-Greek, Indo-Parthian, and Kushana kings and in certain records outside Gandhara, including parts of central Asia.

- This script was written from right to left and seems to have derived from the north Semitic Aramaic script.

Brahmi script

- The Brahmi script was written from left to right.

- Origin: Scholars debate its origin, with some suggesting indigenous roots and others proposing an Aramaic origin. However, the differences in writing direction and letter forms between Brahmi and Kharoshthi make a common origin unlikely.

- Kharoshthi declined by the 3rd century CE, while Brahmi evolved into various indigenous scripts in South Asia and parts of central and Southeast Asia.

- The different stages of Brahmi are often labeled by dynasties, such as Ashokan Brahmi, Kushana Brahmi, and Gupta Brahmi.

- Gupta Brahmi evolved in the late 6th century into Siddhamatrika or Kutila, characterized by sharp angles at the lower right corners of letters. After this period, regional differences became more pronounced.

- Modern north Indian scripts emerged from Siddhamatrika, with Nagari or Devanagari standardized by about 1000 CE. Eastern scripts, like proto-Bengali or Gaudi, developed between the 10th and 14th centuries, leading to the emergence of Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, and Maithili scripts in the 14th–15th centuries. The Sharada script also emerged during this time in Kashmir and surrounding areas.

Tamil script

- The earliest inscriptions in the Tamil language are found in rock shelters and caves, especially near Madurai. These inscriptions are in Tamil–Brahmi, an adaptation of Brahmi for writing Tamil.

- Three southern scripts emerged in the early medieval period: Grantha, Tamil, and Vatteluttu. Grantha was used for writing Sanskrit, while Tamil and Vatteluttu were used for writing Tamil.

- The Tamil script first appeared in Pallava territory in the 7th century CE. Scripts similar to modern Telugu and Kannada began to take shape in the 14th–15th centuries, and the Malayalam script developed from Grantha around the same time.

Bi-script

- Ancient Indian inscriptions include a few bi-script documents where the same language is written in two different scripts. Most instances are from the north-west and consist of short Brahmi–Kharoshthi inscriptions.

- Longer records include an 8th-century Pattadakal pillar inscription of Chalukya king Kirttivarman II, written in Sanskrit in both north Indian Siddhamatrika script and local southern proto-Telugu–Kannada script.

Languages of Inscriptions

- The earliest Brahmi inscriptions, including those of Ashoka, are in dialects of Prakrit. Between the 1st and 4th centuries CE, many inscriptions were written in a mixture of Sanskrit and Prakrit.

- The first pure Sanskrit inscriptions appeared in the 1st century BCE, with the Junagadh rock inscription of the western Kshatrapa king Rudradaman being the first long Sanskrit inscription.

- By the end of the 3rd century CE, Sanskrit gradually replaced Prakrit as the language of inscriptions in northern India. In the Deccan and South India, Sanskrit and Prakrit inscriptions appeared together in the late 3rd/early 4th century CE, with the Sanskrit element increasing over time.

- During the 4th and 5th centuries, there were bilingual Sanskrit–Prakrit inscriptions and those in a mixture of the two languages. After this period, Prakrit fell out of use.

- Between the 4th and 6th centuries, Sanskrit became the premier language of royal inscriptions across India and was associated with high culture, religious authority, and political power, extending even to Southeast Asia.

- Inscriptions began to be composed in regional languages in the 9th and 10th centuries, with Sanskrit inscriptions reflecting local dialect influences in spellings and non-Sanskrit words.

Tamil inscriptions and bilingual Tamil-Sanskrit

- In South India, inscriptions in the old Tamil language (and Tamil–Brahmi script) appeared in the 2nd century BCE and the early centuries CE. Tamil became a significant language for South Indian inscriptions under the Pallava dynasty.

- Bilingual Tamil–Sanskrit Pallava inscriptions from the 7th century onwards feature Sanskrit for invocations, genealogies, and conclusions, while Tamil details the grants.

- Kings of the Chola and Pandya dynasties issued Tamil and bilingual Sanskrit–Tamil inscriptions. Numerous Tamil inscriptions were inscribed on temple walls in early medieval South India.

Kannada and bilingual Kannada-Sanskrit

- The earliest Kannada inscriptions date from the late 6th/early 7th century CE. From this period, private donative records in Kannada and some royal grants were also in this language.

- Bilingual Sanskrit–Kannada inscriptions exist, and a 12th-century inscription from Kurgod in Karnataka is in three languages: Sanskrit, Prakrit, and Kannada.

Telugu and Malayalam

- The late 6th century epigraphs of the early Telugu Chola kings mark the beginning of Telugu as a language of inscriptions. Numerous private donative records in Telugu followed.

- Malayalam inscriptions emerged around the 15th century.

Marathi, Oriya, Hindi, Gujarati

- Inscriptions in modern north Indian languages (New Indo-Aryan) such as Marathi and Oriya can be identified from the 11th century.

- Inscriptions in dialects similar to present-day Hindi appear in Madhya Pradesh from the 13th century, and Gujarati inscriptions can be identified from the 15th century.

Classification of Inscriptions

1. Classification into Official and Private Records

Inscriptions can be classified into official and private records based on whose behalf they were inscribed.

Official Records

- Official records convey royal orders and decisions regarding social, religious, and administrative matters to officials and the general public.

- Examples of official records include Ashoka’s edicts and royal land grants.

Private Records

- Private records consist of inscriptions that document grants made by private individuals or guilds to temples, Buddhist, or Jaina establishments.

2. Classification According to Content and Purpose

Commemorative Inscriptions

- Commemorative inscriptions record specific events or achievements. For example, the Lumbini pillar inscription of Ashoka commemorates the king's visit to the Buddha’s birthplace.

Donative Inscriptions

- Donative inscriptions refer to gifts of money, cattle, land, etc., primarily for religious purposes. These gifts were made not only by kings and princes but also by artisans and merchants.

- Examples include inscriptions in favor of religious establishments, such as those inscribed on shrine walls, railings, and gateways. Inscriptions also recorded the excavation and donation of caves to ascetics.

- Donative inscriptions often include records of the installation of religious images, sometimes inscribed on the images themselves. Others document investments of money from which lamps, flowers, incense, etc., were to be provided for the worship of the deity.

Royal Land Grants

- Inscriptions recording land grants, primarily made by chiefs and princes, are crucial for studying the land system and administration in ancient India.

- These inscriptions, found on stone or copper plates, document grants of lands, revenues, and villages to monks, priests, temples, monasteries, vassals, and officials.

- The earliest stone inscriptions recording land grants with tax exemptions are Satavahana and Kshatrapa epigraphs from Nashik.

- Notable examples of copper plate grants include mid-4th century Pallava and Shalankayana grants, and the late 4th century CE Kalachala grant of king Ishvararata.

- Copper plate grants became more frequent in the early medieval period.

Prashastis

- Prashastis are eulogies that begin most royal inscriptions (and some private ones).

- They praise the attributes and achievements of kings and conquerors, often ignoring their defeats or weaknesses.

- Examples include the Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela, a 1st century BCE/1st century CE king of Kalinga, and the Allahabad prashasti of the 4th century Gupta emperor Samudragupta.

Miscellaneous Types of Inscriptions

- Miscellaneous types of inscriptions include labels, graffiti left by pilgrims and travelers, religious formulae, and writing on seals.

- Some inscriptions from Madhya Pradesh provide a summary of Sanskrit grammar basics.

- 'Footprint inscriptions' accompany engraved footprints of holy figures, kings, or noteworthy individuals.

Inscriptions as a Source of History

Advantages

- Inscriptions, compared to manuscripts, are durable and contemporaneous to the events they describe.

- Changes and additions in inscriptions are usually easy to detect.

- Inscriptions reflect actual practices, making them valuable for understanding political history.

- They provide insights into political structures, administrative systems, and revenue systems.

- Inscriptions shed light on settlement patterns, agrarian relations, and class and caste structures.

- They offer dateable information on religious sects, institutions, and practices.

- Inscriptions help identify and date sculptures and structures, contributing to the history of iconography, art, and architecture.

- They are a rich source of historical geography and reflect the history of languages, literature, and performing arts.

Numismatics: The Study of Ancient Indian Coins

Numismatics is the study of coins, and it provides valuable insights into the history and economy of ancient India. Unlike today, where paper currency is common, ancient Indian currency primarily consisted of metal coins. These coins were made from various metals such as copper, silver, gold, and lead.

Types of Coins and Their Materials

Ancient Indian coins were made from different types of metals, including:

- Copper: Coins made from copper were common in ancient India.

- Silver: Silver coins were also prevalent and often used for trade.

- Gold: Gold coins were valuable and used for significant transactions.

- Lead: Some coins were made from lead, although this was less common.

Coin molds made of burnt clay have been discovered in large numbers, particularly from the Kushan period. These molds were used to create coins, and their presence indicates the importance of coinage during that time. However, the use of such molds declined significantly after the Gupta period.

- Storage of Wealth: In ancient times, without a modern banking system, people stored their wealth in earthenware pots and brass vessels. These containers held not only Indian coins but also coins minted in foreign lands, such as those from the Roman Empire. Many hoards of coins have been discovered in various parts of India, revealing the diverse origins of the coins.

- Early Coins and Their Designs: The earliest Indian coins featured simple symbols, while later coins depicted images of kings, deities, and inscriptions with their names and dates. This evolution in coin design reflects the changing political and cultural landscape of ancient India.

History of Indian Coinage

- During the Stone Age, people relied on barter for trade as there was no concept of currency or coinage. The Harappans, for example, engaged in extensive trade networks based on barter. The Rig Veda mentions terms like nishka and hiranyapinda, which refer to gold ornaments and globules, but these cannot be considered coins. Later Vedic texts introduce terms that may have referred to metal pieces of specific weight, but not fully developed coins.

- The earliest evidence of coinage in the Indian subcontinent dates back to the 6th–5th centuries BCE, coinciding with the rise of states, urbanization, and increased trade. Buddhist texts and the Ashtadhyayi mention various terms related to coinage, such as kahapana, nikkha, suvarna, and others. The basic unit of Indian coin weight systems was the raktika, ratti, or rati, derived from the red-and-black gunja berry seed. In South India, coin weight standards were based on the manjadi and kalanju beans.

Punch-Marked Coins

Punch-marked coins are the oldest found in the subcontinent, primarily made of silver, with some in copper. These coins were often rectangular, square, round, or irregular in shape. Blanks for these coins were cut from metal sheets, and symbols were hammered onto them using dies or punches. Most silver punch-marked coins weighed around 32 rattis or about 56 grains and were widely circulated across the subcontinent, remaining in use until the early centuries CE, particularly in peninsular India.

Punch-marked coins from northern India are categorized into four main series based on weight, punch marks, and circulation area:

- Taxila Gandhara type: Northwest, heavy weight standard, single punch type.

- Kosala type: Middle Ganga valley, heavy weight standard, multiple punch marks.

- Avanti type: Western India, light weight standard, single punch mark.

- Magadhan type: Light weight standard, multiple punches.

Changes in coinage patterns reflected political shifts, such as the rise of the Magadhan empire, which led to the dominance of Magadhan punch-marked coins. Although these coins lacked legends, most were likely issued by states. Evidence of city and guild issues suggests similar practices during the punch-marked coin period.

- Symbols and Marks: Coins featured symbols like geometric designs, plants, animals, and religious or political motifs. Primary and secondary punch marks were common, with secondary marks added later without heating the coins.

- Uninscribed Cast Coins: Uninscribed cast coins made of copper or copper alloys emerged after punch-marked coins, found throughout the subcontinent except the far south. These coins were created by melting metal and pouring it into molds, with clay molds discovered at various sites and a bronze mold found in central India. The simultaneous discovery of punch-marked and uninscribed cast coins at some archaeological sites indicates their overlapping usage.

- Uninscribed Die-Struck Coins: Uninscribed die-struck coins, mostly in copper and occasionally in silver, featured symbols similar to punch-marked coins and were struck onto coin blanks with carved metal dies. Minting of such coins likely began around the 4th century BCE, with large quantities found at sites like Taxila and Ujjain.

- Die-Struck Indo-Greek Coins: The die-struck Indo-Greek coins of the 2nd/1st century BCE marked a new phase in Indian coinage. These coins were well-crafted, usually round, and primarily made of silver, with some in copper, billon, nickel, and lead. The obverse displayed the name and portrait of the issuing ruler, with the reverse featuring religious symbols. Notable features include bilingual and bi-script coins, with the issuer's name in Greek on the obverse and in Prakrit on the reverse, typically in the Kharoshthi script.

- Kushana Coins: The Kushanas (1st–4th centuries CE) were the first subcontinental dynasty to mint large quantities of gold coins, although their silver coins were rare. They also issued many low-denomination copper coins, reflecting the expanding money economy. Kushana coins featured the king's figure, name, and title on the obverse, with deities from various pantheons on the reverse. Legends were in Greek or Kharoshthi.

- Local Coins: Local, tribal, janapada, or indigenous coins from the 3rd century BCE to the 4th century CE provide insights into the history of northern and central Indian dynasties. These coins, mainly cast or die-struck in copper or bronze, include some silver coins and rare examples in lead and potin. They were issued by chieftains, kings, and non-monarchical states like the Arjunayanas, Uddehikas, Malavas, and Yaudheyas. Some coins bore city names, suggesting issuance by city administrations, while others may have been issued by merchant guilds.

- Satavahana Coins: In the Deccan, Satavahana kings issued copper and silver coins, with some small-denomination coins made of lead and potin. Most Satavahana coins were die-struck, with some cast coins. Legends were typically in Prakrit and Brahmi, while portrait coins used a Dravidian language and Brahmi. Punch-marked coins continued to circulate alongside Satavahana issues.

- Ikshvaku and Western Deccan Coins: The Ikshvakas of the lower Krishna valley (3rd–4th centuries) issued lead coins similar to Satavahana coins. In the western Deccan, there was a higher demand for silver currency, with Kshatarapa ruler Nahapana introducing silver currency in the Nashik area. Roman gold coins also entered peninsular India in large quantities, used for significant transactions or as currency reserves. Locally made imitations of Roman gold coins were also found.

- South Indian Coins: Punch-marked coins found in South India have been identified as dynastic issues based on their symbols. Increasing evidence of dynastic issues (some with portraits) associated with the Cholas, Cheras, and Pandyas has been observed. Coins with the legend Valuti are linked to the Pandyas, while silver coins with Chera king portraits and legends like Makkotai have been discovered.

- Gupta Coins: The imperial Gupta kings issued well-crafted die-struck gold coins known as dinaras, predominantly found in north India. The obverse depicted the king in various poses, often martial, while the reverse featured religious symbols reflecting the kings' affiliations. The metallic purity of gold coins declined later in Skandagupta's reign, and while the Guptas issued silver coins, copper coins were rare.

Numismatic History of the Early Medieval Period

- The numismatic history of the early medieval period remains a topic of ongoing debate among historians. While some scholars describe this era as characterized by a feudal order, noting a decline in coinage alongside a decrease in trade and urban centers, followed by a revival in the 11th century, this hypothesis can be challenged.

- Although there was a noticeable decline in the aesthetic quality of coins, the variety of coin types, and the content of their messages—many coins lacking identifiable names or titles—evidence presented by John S. Deyell suggests that there was no significant decline in the volume of coins in circulation during this period.

Base Metal Alloy Coin Series

Various dynasties in the early medieval period issued coins made from base metal alloys. These coins played a role in the evolving monetary landscape of the time.

Regional Variations in Coinage

- Rajputana and Gujarat: In the Ganga valley, billon coins circulated within the Gurjara-Pratihara kingdom, while different coin types were in circulation in Rajputana and Gujarat.

- Sindh: The Arab governors of Sindh minted copper coins between the mid-8th and mid-9th centuries, contributing to the region's numismatic history.

- Kashmir: In Kashmir, the use of copper coins was supplemented by bills of exchange (hundikas) denominated in terms of coins or grain, as well as the use of cowries, reflecting a diverse monetary system.

- Bengal: During the 6th to 7th centuries, kings of Bengal, such as Shashanka, issued gold coins. However, no coin issues from the Pala and Sena dynasties have been identified. It has been suggested that references to currency units in their inscriptions do not represent actual coins but theoretical units of value composed of a fixed number of objects, such as cowries.

- Despite this, silver coins known as Harikela coins circulated in Bengal between the 7th and 13th centuries, with corresponding local eastern series issued in the name of various localities.

- Western Deccan: In the western Deccan, some early medieval coin types have been tentatively linked to the Chalukyas of Badami. Although gold and silver coins found in the Andhra region have been attributed to the early eastern Chalukyas, there is a significant gap of about three centuries until the late 10th century.

During this time, there was a revival of gold and copper coinage under the later kings of this dynasty. The attribution of certain gold and silver coins to the Chalukyas of Kalyana (8th to 12th centuries) and to the Kalachuri Rajputs remains uncertain.

Coins issued by the Kadambas of Goa (11th to 12th centuries) have been identified, and a few gold coins have been attributed to the Shilaharas of the western Deccan (11th century). - Far South: In the far south, coins featuring lion and bull motifs, some inscribed with titles, have been associated with the Pallavas. The tiger crest is the emblem on Chola coins. Seals from several Chola copper plate inscriptions display the tiger, fish (the Pandya emblem), and bow (the Chera emblem), indicating the Cholas' political supremacy over these two dynasties.

The appearance of these three emblems on numerous gold, silver, and copper coins suggests that these were Chola issues. Gold coins discovered at Kavilayadavalli in Andhra Pradesh feature the tiger, bow, and some indistinct marks. The obverse bears the Tamil legend sung, likely a short form of sungandavirttarulina (abolisher of tolls), one of the titles of the Chola king Kulottunga I. The legends on the reverse may indicate the names of mint towns.

The last phase of Chola rule is primarily represented by copper coins. Coins, mostly copper, from the early medieval Pandyas have been predominantly found in Sri Lanka. - Cowries: Cowries also served as a form of currency, although their purchasing power was relatively low. They appear in substantial numbers in post-Gupta times but may have been used earlier. In many parts of early medieval India, cowries continued to be utilized alongside coins.

At Sohepur in Orissa, for instance, 25,000 cowries were found alongside 27 Kalachuri coins. At Bhaundri village in Lucknow, 54 Pratihara coins were discovered alongside 9,834 cowries. Cowries were likely employed by people for small-scale transactions or in situations where coins of small denominational value were scarce. The market value of cowries fluctuated based on demand and supply.

Coins as Historical Sources

- Coins are subjected to wear and tear during circulation, leading to a gradual decrease in their weight. This characteristic allows numismatists to arrange coins in a chronological sequence. The legends inscribed on coins provide valuable information about the history of languages and scripts.

- Coins, used for various purposes such as donations, payments, and exchanges, offer significant insights into economic history. Some coins were issued by guilds of merchants and goldsmiths with the rulers' permission, indicating the growing importance of crafts and commerce. Coins are integral to monetary history, encompassing the production and circulation of coinage, monetary values, and issue frequencies and volumes.

- Monetary history is a crucial aspect of exchange and trade history. The widespread distribution of Kushana coins reflects the flourishing trade of the period, while ships depicted on certain Satavahana coins highlight the significance of maritime trade in the Deccan. Roman coins found across India provide insights into Indo-Roman trade. The largest number of Indian coins dates to the post-Maurya period, with the Guptas issuing the most gold coins, indicating robust trade and commerce, especially in the post-Maurya and much of the Gupta period.

- However, the scarcity of post-Gupta coins suggests a decline in trade and commerce during that time. The few coin series issued by guilds underscore the importance of these institutions. Coins are often viewed as indicators of economic prosperity or decline, reflecting the financial conditions of ancient states.

- Historians interpret the debasement of coins as a sign of financial crises or economic decline, as seen during the later Guptas. However, debasement can also be a response to increased demand for coins due to heightened economic transactions, especially when the supply of precious metals is restricted.

- Dates are rarely found on early Indian coins, with exceptions like western Kshatrapa coins that provide dates in the Shaka era and some Gupta silver coins that record the regnal years of kings. Whether dated or undated, coins discovered in archaeological excavations often assist in dating layers. For example, at the site of Sonkh near Mathura, excavated levels were categorized into eight periods based on coin finds.

- Coins are vital for political history, serving as important royal message-bearing media. The circulation area of dynastic issues helps estimate the extent and frontiers of empires, aiding in reconstructing the history of various ruling dynasties, particularly the Indo-Greeks who ruled in India from north Afghanistan in the second and first centuries BCE.

- However, caution is necessary as coins made of precious metals had intrinsic value and often circulated beyond the issuing state's borders. They sometimes continued to circulate after a dynasty lost power. Multiple currency systems could coexist in an area, necessitating an understanding of overlapping spheres of coin circulation.

- Numismatic evidence is particularly significant for political history in India between c. 200 BCE and 300 CE. Most Indo-Greek kings are primarily known from their coins, which also provide information on the Parthians, Shakas, Kshatrapas, Kushanas, and Satavahanas.

- Coins of over 25 kings with names ending in ‘mitra’ have been found from east Punjab to Bihar's borders. Coins from various parts of north and central India (Vidisha, Eran, Pawaya Mathura, etc.) mention kings with names ending in ‘naga,’ about whom little is known from other sources. Coins also shed light on ancient political systems, as seen in the term ‘gana’ on coins of the Yaudheyas and Malavas, indicating their non-monarchical polity.

- City coins suggest the significance and possible autonomy of certain city administrations. Occasionally, numismatic evidence provides biographical details about kings, such as the marriage of Gupta king Chandragupta I to a Lichchhavi princess, known from coins commemorating the marriage.

- Coins also record the performances of the ashvamedha sacrifice by Samudragupta and Kumaragupta I, with different coin types highlighting various aspects of Samudragupta's personality.

- Coins portray kings and gods and contain religious symbols and legends, offering insights into art and religion. The depiction of deities on coins provides information about kings' personal religious preferences, royal religious policy, and the history of religious cults.

For example, figures like Balarama and Krishna on Indo-Greek coins indicate the popularity of these cults. The diverse figures from Indian, Iranian, and Graeco-Roman traditions on Kushana coins reflect their eclectic religious views and the variety of cults in their empire.

Conclusion

The various literary and archaeological sources for ancient and early medieval India have their specific potential and limitations, which historians must consider. Interpretation is crucial for analyzing evidence from ancient texts, archaeological sites, inscriptions, and coins.When multiple sources are available, their evidence should be correlated. Correlating evidence from texts and archaeology is especially important for a comprehensive history of ancient and early medieval India. However, given the inherent differences between literary and archaeological data, integrating them into a cohesive narrative can be challenging.

|

71 videos|819 docs

|

FAQs on Archaeological Sources - History Optional for UPSC (Notes)

| 1. What is the main focus of field archaeology? |  |

| 2. What are some common excavation methods used in field archaeology? |  |

| 3. What are some modern trends in field archaeology? |  |

| 4. How does marine archaeology differ from traditional field archaeology? |  |

| 5. What is the significance of ethno-archaeology in the field of archaeology? |  |

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|