Channel Morphology | Geography Optional for UPSC (Notes) PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Define Channel Morphology |

|

| Factors Controlling Channel Morphology |

|

| Channel Classification |

|

| Lateral Channel movement |

|

| Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) of Channel Morphology |

|

Define Channel Morphology

- Channel morphology, also known as river channel morphology or river morphology, is a comprehensive study of river channels from a geographical perspective and fluid dynamics aspect. It involves examining various channel-related aspects such as channel patterns, geometry, and the factors that influence these forms.

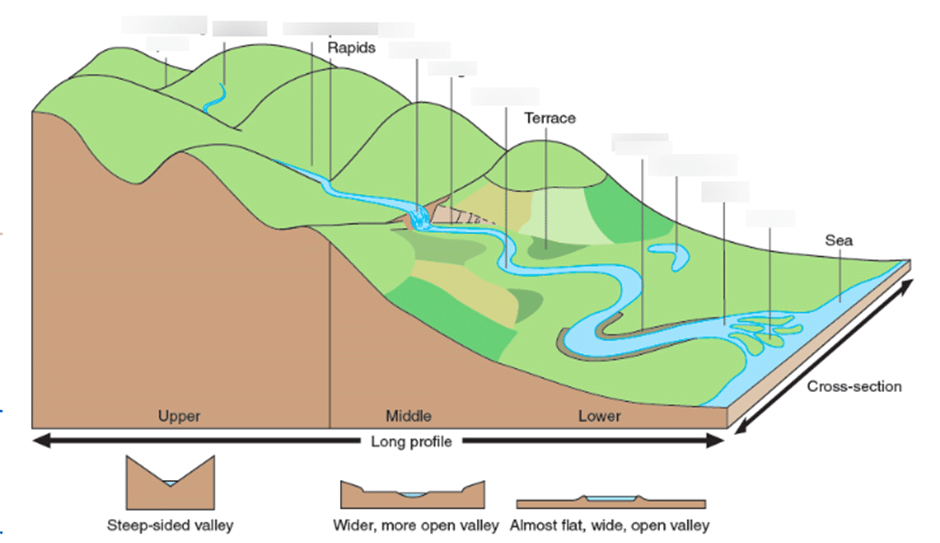

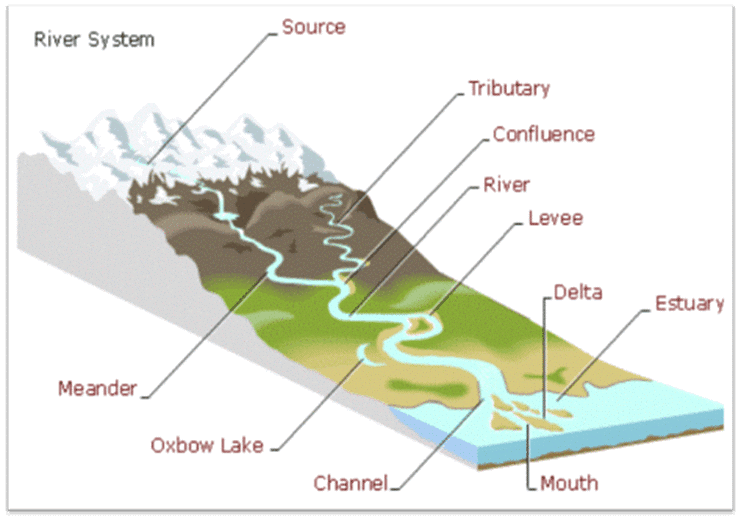

- The factors that affect a channel are the processes that modify it, including the network of tributaries that connect to the main river channel within the drainage basin. Channel development is primarily controlled by two factors: water flow or discharge (in terms of volume and velocity) and sediment movement. These factors are influenced by the channel slope or gradient, which can range from steep to gentle slopes depending on the altitude variations the channel traverses.

- The interrelationship between these parameters can be qualitatively described by Lane's Principle (also known as Lane's relationship), which states that the product of the sediment load and bed grain size is proportional to the product of discharge and channel slope. In simpler terms, this principle highlights the balance between the forces of water flow and sediment movement that shape a river channel's morphology.

Channel

- A channel, in the context of physical geography, refers to the narrow pathway of a water body, such as a river or a strait. It is characterized by its bed and banks that outline the path of the river or stream. The entire network of river channels, including their connecting branches in the form of tributaries, is proportional to the size of the valley they traverse.

- Channels can be occupied by various types of streams, including permanent ones that flow year-round, intermittent ones that flow at certain times, and ephemeral ones that only flow during and after rain events.

- During floods, the volume of water in a river may exceed the channel's capacity, causing the water to overflow its banks and flood the surrounding floodplain. In this sense, the term "channel" is often used interchangeably with "strait," which refers to a relatively narrow body of water connecting two larger bodies of water. In a nautical context, the terms "strait," "channel," and "passage" can be used interchangeably.

- For instance, in an archipelago, the water between islands is commonly referred to as a channel or passage. A well-known example of a channel is the English Channel, which is the strait separating England and France.

Channel Structure

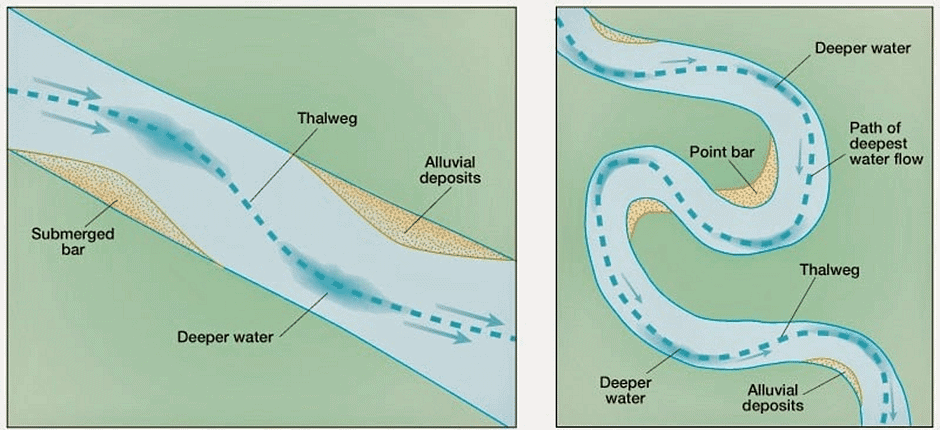

- Channel structure refers to the various components that make up a river channel, including channel banks, channel bed, and the Thalweg.

- The channel bed is the primary pathway through which a river flows. It is the base of the river, on which the water runs and moves downstream.

- Channel banks are the two sides of the river bed that confine the water flow. These banks can be made up of various materials, such as soil, rocks, and vegetation, and help to shape the overall structure of the river channel.

- The Thalweg is a continuous line that connects the lowest points of the stream channel. It is essentially the deepest part of the river bed, where the flow of water is generally the fastest and the most erosive, often resulting in the formation of deeper channels over time.

River Processes

- River processes involve the wearing away, transportation, and deposition of materials by the river. These processes are essential for shaping the landscape and creating various landforms.

- Erosion is the process of gradually wearing away materials, such as rocks and soil, by the river's movement. There are four primary methods of erosion: attrition, corrosion, corrasion, and hydraulic action. Attrition occurs when the river's load, or the materials it carries, collide with one another, causing them to break apart. Corrasion, also known as abrasion, happens when the river's load grinds against the riverbanks and bed, breaking off pieces. Corrosion, or solution, is the process of the river's water dissolving its load, as well as the bed and banks. Hydraulic action refers to the erosion caused by water and air entering cracks in the riverbanks and bed, which increases pressure and breaks apart the materials.

- Transportation is the process of the river moving its load from one place to another, using excess energy. There are four main ways the river transports materials: traction, saltation, suspension, and solution. Traction involves large pieces of load rolling along the river bed, while saltation is the process of smaller loads bouncing along the river bed. Suspension refers to tiny pieces of load being carried within the river's flow, and solution involves dissolved materials being transported within the water. Flotation is when materials are transported on the river's surface.

- The term "load" refers to the materials transported by the river. If the materials are being transported along the river bed, they are called bedload. If they are transported within the river's flow, they are often referred to as suspended load.

- Deposition occurs when the river no longer has enough energy to transport its load, causing it to put down or deposit the materials in its path. This process leads to the formation of various landforms, such as deltas and alluvial fans.

Factors Controlling Channel Morphology

Channel morphology, which includes aspects such as channel pattern and movement, is influenced by two groups of factors: independent factors and dependent factors.- Independent factors are those that are externally imposed on the watershed and are related to the landscape's characteristics. These factors include geology, climate, and human activities. The geology of a watershed is influenced by various processes at the landscape level, such as volcanism, tectonics, and to a smaller extent, surface processes like erosion and deposition. These factors affect the distribution, structure, and type of bedrock, surface materials, and topography within a watershed (Montgomery 1999).

- Climate is another key independent factor that influences channel morphology at the landscape scale. It plays a crucial role in determining the amount of rainfall and water flow in the stream channel. Human activities, such as deforestation, construction, and agriculture, can also lead to significant changes in the watershed conditions.

- Dependent factors, on the other hand, are determined by the independent variables mentioned above. These include sediment supply, stream discharge, and vegetation (Montgomery and Buffington 1993; Buffington et al. 2003). Furthermore, time is also an essential independent variable that influences channel morphology.

Dependent Factors

Dependent factors in channel morphology are variables that change and adapt according to independent conditions. The morphology of a channel is influenced by the combined effects of these dependent landscape variables, which in turn respond to changes in these factors by adjusting one or more of the dependent channel variables.

- Sediment supply is one of the dependent factors and is determined by the frequency, volume, and size of material delivered to the channel. Stream discharge is another dependent factor, which is characterized by the frequency, magnitude, and duration of stream flows. The variation in stream discharge over time and space has a significant impact on channel morphology.

- Riparian vegetation is the third dependent factor that influences channel morphology. It helps control bank erodibility and near-bank hydraulic conditions, and also serves as a source of in-channel large woody debris (LWD). Traditional models of channel morphology primarily considered stream flow and sediment transport rate, assuming that transport rate and sediment supply were equal under equilibrium conditions. However, these models did not account for the role of vegetation or other boundary conditions, which are crucial in determining channel morphology.

In addition to riparian vegetation, important boundary conditions include elements found within the stream channel and those that may affect the channel's ability to migrate laterally or build vertically. Key boundary conditions include:

- Channel gradient, which is determined by the valley slope. The maximum possible gradient of a stream channel depends on the slope of the valley.

- Bank composition and structure, which influence bank erodibility based on the sedimentology and Bedrock and other non-erodible units, such as colluvial material, compact tills, and lag glaciofluvial deposits, which can limit lateral and vertical channel migration and determine stream channel alignment.

- Erodible sediment stored in valley bottoms, including floodplains, fans, or terraces, as well as alluvial sediments, lacustrine, marine, and glacial outwash deposits, and fine-textured colluvium.

- Human channel alterations, such as bridge crossings and flood protection works.

These boundary conditions are primarily influenced by the geomorphic history of a landscape and the history of human intervention. As a result, the current morphology of a stream is a product of both present-day and historical watershed processes.

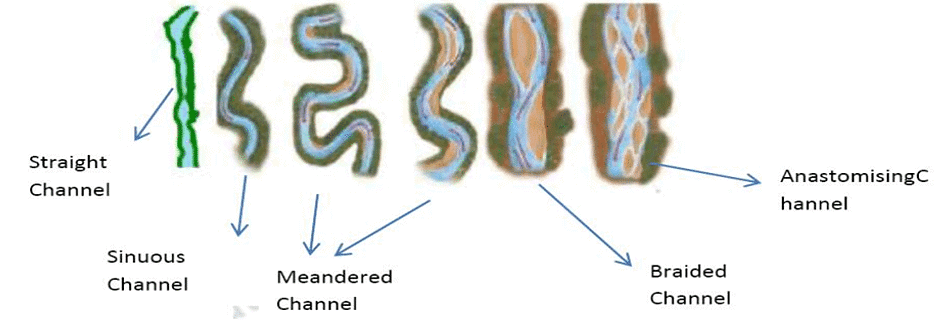

Channel Classification

- The channels can be classified into different categories based on different criteria. These criteria include the constituent material of the river channel and the shape or pattern of the river channel. The pattern of the channel is described as channel form. Channels exist in a variety of forms. There are a wide variety of stream channel types based on their forms, such as Single Thread Sinuous Rivers, Wandering Rivers or a meandering river, Braided Rivers, etc. enclosed by the materials of its bed and banks.

- Bedrock Channel: When the river bed has the cover of rocks rather than the sediment cover and the river erodes into the rock. These are the channels that flow through non-erodible materials (e.g., bedrock, coarse colluvium, and non-erodible glacial deposits) and their boundary conditions tend to dominate the channel morphology. This type of channel usually has a limited sediment supply and a morphology that is largely determined by the structure and composition of the material through which it flows. Bedrock channels, for example, frequently run along faults or other geologic planes of weakness within the rock. Overall, these channels are relatively insensitive to disturbances, including disturbances from changes occurring upstream (i.e., the channel is relatively stable), but bedrock channels are very effective at transferring disturbances from upstream to downstream reaches.

- Alluvial Channel: When the river cuts the river-transported rock debris, or alluvium, these are referred to as the alluvium channel. These channels are more regular.

- Schumm (1985) has proposed a more detailed channel classification that included three categories:

- bedrock channel,

- semi-controlled channel, and

- alluvial channel;

- But this classification was found to be not addressing the variable geotechnical properties associated with the landforms.

- So Kellerhals in 1976, has suggested that the categories should be based on the materials that determine channel bed and bank strength and the channel’s threshold of erodibility. Based on this, three categories of materials constituting channel could be identified (1) nonerodible, (2) semi-erodible, and (3) erodible. Although, these terms (as opposed to the conventional “non alluvial” and “alluvial”) are more useful, but by definition these are contradictory, as all alluvial material is erodible and many non-alluvial materials are also highly erodible (e.g., marine and glaciofluvial deposits). Similarly, some alluvial materials are far less erodible than others; for instance, armored channel beds developed by fluvial processes are much more resistant to movement than other alluvium such as gravel-bar deposits, which are rearranged on an annual basis.

- The other classification is based on the shape assumed by the river channel, called a planform pattern. In the words of Leopold (1957) “Channel pattern is used to describe the plan view of a reach of river as seen from an airplane and includes meandering, braiding, or relatively straight channels. Natural channels characteristically exhibit alternating pools or deep reaches and riffles or shallow reaches, regardless of the type of pattern.” The shape of the channel is largely decided by the sinuosity of the river. Sinuosity refers to the ratio of the measured channel distance divided by the straight-line distance of the valley from the beginning of the channel reach to the end of the channel reach.

- Mollard (1973) identified 17 planform channel types that were related to both the physiographic environment in which channels flowed, and the materials that made up the channel bed and banks. He based this channel pattern classification on the factors controlling morphology, specifically streamflow, sediment supply, the relative dominance of fluvial transport processes, and the materials within which the channel is formed.

- Church (1992) classified channel patterns on the basis of the caliber and volume of sediment supply that in turn decides the sinuosity of the river channel. He has separated the patterns into phases of river channel flow during its upper course to lower course, related to how the supplied sediment gets transported.

- Braided River Channel: In other situations, the channel becomes too active for stable vegetated islands to develop, and the system divides into numerous individual channels that divide and recombine around unstable gravel bars; these are called “braided channels.” Anastomosing rivers or streams are similar to braided rivers in that they consist of multiple interweaving channels but they typically consist of a network of low-gradient, narrow, deep channels with a stable bank.

Hydraulic Geometry of Channel

- The analysis of the relationship among stream discharge, channel shape, sediment load and slope, has been called as hydraulic geometry of stream channels.

- Gaging stations around the world maintained by the respective governments make recordings along the rivers all over the world. At these stations, the water surface level, channel shape, stream velocity, amount of dissolved and suspended minerals and other variables are periodically recorded. These records provide a detailed history of river flow.

- In 1953, L.B.Leopold and Thomas Maddock published an elaborate analysis of thousands of measurements from stream gaging stations all over the world. It was they who called their analysis of the relationship among stream discharge, channel shape, sediment load and slope as hydraulic geometry of stream channels.

- To understand the hydraulic geometry of stream channels there is need to study the changes in following four parameters at different gaging stations under varying conditions spanning from low flow to bank full discharge and flood:

- Channel width,

- Channel depth,

- Stream velocity,

- Suspended load

- These four parameters increases as some small, positive power function of discharge, based on the following equations:

- The numerical values for arithmetic constants a, c, and k is not very significant for the hydraulic geometry of stream channels. They are constants of proportionality that convert a given value of discharge into the equivalent values of width, depth and velocity. The numerical values of the exponents b, f and m are very important as they describe the changes of width, depth and velocity for a specified change of discharge are very important.

- During flood, the water rises and stream channel width, depth and current velocity all increase at the gaging stations. This is clearly evident during the flood situation, as the regularity of the average changes drastically.

- In a downstream direction, the changes in channel shape and stream velocity are more significant as was emphasised by Leopold and Maddock in 1953. River discharge in humid area increases downstream.

- They proved that as mean discharge of a river increases downstream, channel width, channel depth, and mean current velocity all increase.

- Leopold and Maddock showed that not only the effluent rivers get both wider and deeper as they grow larger downstream but against the popular belief they also proved that average current velocity and increases downstream. This is because of the high-velocity current in a upper coarse of the river flows in circular eddies, with backward as well as forward motion.

- The numerical value of the three exponents b, f, and m that describe the variations in width, depth and velocity with variable discharge at gaging station are not the same as those that describe the downstream increases in width, depth, and velocity with progressively increasing mean annual discharge.

- Leopold and Maddock said that in a downstream direction, at mean annual discharge, the average values for the exponents were found to be B=0.5, f=0.4, and m=0.1.

- These values show that channel width increases most rapidly with mean annual discharge (as the square root of the discharge), depth next most rapidly, and mean velocity increases only slightly, in the downstream direction.

- Leopold and Maddock proposed that the increasing depth downstream permits more efficient flow in a river and compensates for the decreasing slope, thus providing a slight net increase in velocity at mean annual discharge.

- Thus, the channel width, depth, and velocity change with the streamflow, and against the popular belief, the velocity increases though only slightly in the downstream direction.

Channel Stability and Movement

- Channel stability refers to a channel's tendency for vertical or lateral movement, as described by Church (2006). This stability is constantly changing as sediment is deposited or transported away, which can occur either along the banks of the stream or within the channel itself. These deposits can lead to alterations in the channel's patterns, and any noticeable changes in these patterns can signal significant shifts in both the watershed and the factors that influence its morphology.

- Geomorphologists can provide evidence of these channel changes, which can then be used by researchers as an indicator of the environmental health of the watershed. It is important to note that different channel types respond differently to changes in sediment supply or discharge. These responses can manifest as either vertical shifts (such as aggradations or degradation, which can be observed in the upward or downward movement of the channel bed) or lateral shifts (where the bed and banks move sideways, as seen in old or abandoned channels on a floodplain).

- In summary, channel stability and movement are crucial factors in understanding the health of a watershed. By observing changes in channel patterns and how different channel types respond to sediment supply and discharge, researchers can gain valuable insight into the overall environmental health of the region.

Vertical Channel shifts:

- Vertical channel shifts refer to the changes in the width-to-depth ratio of a river channel. These shifts occur as a response to variations in sediment load and transportation capacity. When the sediment supply exceeds the river's ability to transport it, the excess sediment accumulates and causes aggradation. Conversely, when the sediment supply is lower than the river's transportation capacity, sediments are removed, leading to degradation.

- Aggradation is the process wherein sediments are deposited within the river channel, causing the width-to-depth ratio to increase. This in turn reduces the stability of the channel. An aerial view of a river experiencing aggradation would show a noticeable expansion of sediment deposits within the channel over time.

- On the other hand, degradation refers to the removal of sediments from the river channel, which happens when the river's transportation capacity exceeds the sediment supply. This process can lead to the narrowing and deepening of the channel.

In summary, vertical channel shifts are changes in the width-to-depth ratio of a river channel as a result of variations in sediment load and transportation capacity. Aggradation occurs when sediment supply surpasses the river's capacity to transport it, leading to sediment deposition and a decrease in channel stability. Degradation, conversely, takes place when sediment supply is lower than the river's transportation capacity, leading to the removal of sediments and potential channel narrowing.

Lateral Channel movement

- Lateral channel movement refers to the shifting of a river or stream across a flat valley surface, which can indicate changes in the conditions upstream. This movement can be caused by progressive bank erosion, which is the gradual wearing away of the riverbank due to sediment buildup in the channel or natural meandering processes. On the other hand, channel avulsion is a more sudden and significant shift in the channel's position to a new or old part of the floodplain or a minor change within a braided channel or other active channels.

- The lateral movement of a channel affects the riparian zone, which is the area where land meets a river or stream. This movement can cause erosion in some areas and buildup in others. The limits of lateral channel movement are determined by the channel's boundary conditions and its relationship with the valley it flows through. If there are no constraints like valley confinement, bridges, or dykes, and the valley is filled with erodible material, the channel can potentially erode across its entire floodplain.

- When a valley is wider than the channel, there is potential for lateral channel movement. In confined systems where the valley is only slightly wider, the extent of lateral movement is limited. In forested valleys, the bank strength provided by riparian vegetation can restrict lateral channel movement, allowing for stable channel morphology in environments where it might not otherwise occur.

- Changes in the patterns of in-channel sediment storage, such as bars and islands, can also serve as early indicators of future channel issues. Braided channels are among the most active types of stream channels, characterized by rapid lateral migration rates and often experiencing net vertical aggradation, or the buildup of sediment.

Conclusion

Channel morphology is an essential aspect of studying river channels from both geographical and fluid dynamics perspectives. It encompasses various factors that influence the shape and structure of channels, such as water flow, sediment movement, and the slope of the channel. Channels can be classified based on their constituent materials or their planform patterns, such as straight, sinuous, or meandering channels. Understanding channel morphology is vital to comprehending the processes and factors that shape our landscape and contribute to the formation of diverse landforms.Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) of Channel Morphology

What is channel morphology?

Channel morphology, also known as river channel morphology or river morphology, is the study of river channels from a geographical perspective and fluid dynamics aspect. It involves examining various aspects of the channel, such as patterns, geometry, and the factors that influence these forms.

What are the main factors that control channel morphology?

Channel morphology is primarily controlled by two factors: water flow or discharge (in terms of volume and velocity) and sediment movement. These factors are influenced by the channel slope or gradient, which can range from steep to gentle slopes depending on the altitude variations the channel traverses.

What is the difference between bedrock channels and alluvial channels?

Bedrock channels are those that flow through non-erodible materials, such as bedrock, coarse colluvium, and non-erodible glacial deposits. Their morphology is largely determined by the structure and composition of the material through which they flow. Alluvial channels, on the other hand, are those that flow through river-transported rock debris or alluvium. These channels are more regular and are more sensitive to changes in sediment supply and flow conditions.

How are river channels classified based on their shape or planform pattern?

River channels can be classified into four types based on their planform pattern: straight river channels, sinuous river channels, meandering river channels, and wandering river channels. These patterns are determined by the sinuosity of the river, which refers to the ratio of the measured channel distance divided by the straight-line distance of the valley from the beginning of the channel reach to the end of the channel reach.

What are some of the processes involved in shaping river channels?

River processes that shape channels include erosion, transportation, and deposition. Erosion is the gradual wearing away of materials by the river's movement, transportation is the process of the river moving its load from one place to another, and deposition occurs when the river no longer has enough energy to transport its load, causing it to put down or deposit the materials in its path. These processes lead to the formation of various landforms, such as deltas and alluvial fans.

|

191 videos|373 docs|118 tests

|

FAQs on Channel Morphology - Geography Optional for UPSC (Notes)

| 1. What is channel morphology? |  |

| 2. What factors control channel morphology? |  |

| 3. How are channels classified based on morphology? |  |

| 4. What is lateral channel movement? |  |

| 5. What are some frequently asked questions about channel morphology? |  |

|

191 videos|373 docs|118 tests

|

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|