Colonialism and The Countryside Class 12 History

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Bengal and the Zamindars |

|

| The Zamindars Resist |

|

| The Hoe and the Plough |

|

| A Revolt in the Countryside The Bombay Deccan |

|

| The Deccan Riots Commission |

|

| Timeline |

|

| Conclusion |

|

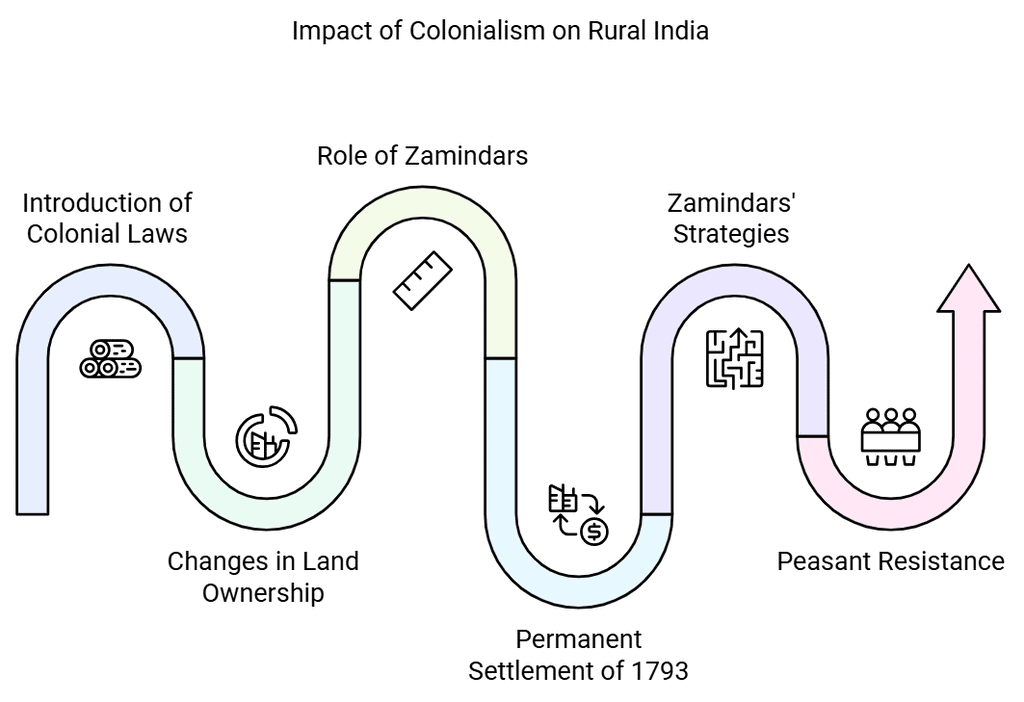

Introduction

The colonial rule in India changed the rural landscape of the country in many ways. Laws introduced by the British government had significant consequences for people in the past. These laws played a role in determining who grew richer and who became poorer, who acquired new land and who lost the land they had lived on, and where peasants turned when they needed money. However, people were not merely passive subjects of these laws; they often resisted them by acting according to their own sense of justice. Through their actions, they influenced how the laws were enforced and, in doing so, altered their effects.

Bengal and the Zamindars

- The colonial rule in Bengal aimed to reorganize rural society with new land rights and revenue systems.

- The Permanent Settlement of 1793 fixed revenue demands on zamindars, making them responsible for collecting rents from peasants.

- Events like the 1797 auction in Burdwan highlighted the strategies zamindars used to navigate these new demands, illustrating the complexities of colonial rule.

- Colonial rule was first established in Bengal, where attempts were made to reorder rural society and establish a new regime of land rights and a revenue system.

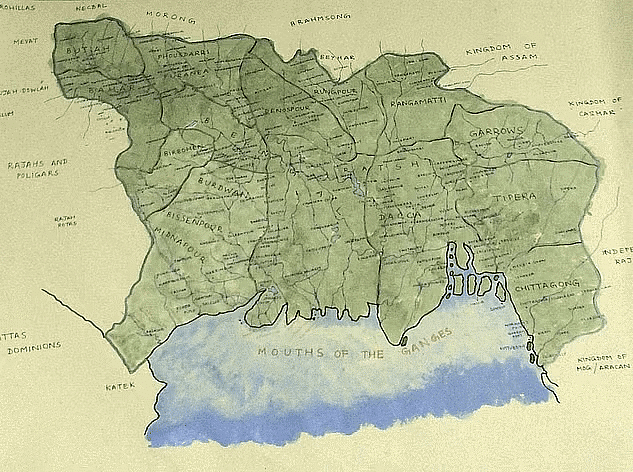

Bengal in 1793

Bengal in 1793

An Auction in Burdwan

- In 1797, a significant auction took place in Burdwan (present-day Bardhaman), where mahals (estates) held by the Raja of Burdwan were being sold.

- The Permanent Settlement was in operation since 1793, with the East India Company fixing the revenue each zamindar had to pay. Failure to pay led to estates being auctioned.

- Despite the estates being sold to the highest bidders, a twist emerged as many purchasers were revealed to be the raja's servants and agents, buying the lands on his behalf.

- The raja's estates were sold in a public auction, yet he continued to maintain control over his zamindari.

- The auction was mostly fake, with the raja controlling over 95% of the sales. This reveals the complicated nature of rural life in eastern India at that time.

The Problem of Unpaid Revenue

- In the late 18th century, not only the estates of the Burdwan raj but over 75% of zamindaris were transferred following the Permanent Settlement.

- The British introduced the Permanent Settlement to address the crises in Bengal's rural economy, such as famines and declining agricultural productivity as witnessed by the 1770s.

- Officials believed that by securing property rights and fixing revenue rates permanently, they could stimulate investment in agriculture, trade, and state revenue resources.

- The fixed revenue demand aimed to ensure a steady income for the East India Company and profits for investors, resulting into a class of wealthy landowners loyal to the British.

Challenges of the Permanent Settlement

- Identifying individuals capable of enhancing agriculture and meeting fixed revenue obligations was a key challenge.

- Ultimately, the Permanent Settlement was established with the rajas and taluqdars of Bengal, reclassified as zamindars responsible for paying perpetual revenue.

- Zamindars, often overseeing numerous villages, were considered revenue collectors rather than mere landowners.

- Each zamindari included multiple villages, treated as one revenue entity by the Company with a fixed revenue demand.

- Zamindars collected rents, paid revenues to the Company, and retained the surplus as their income, facing auction if failing to meet payment obligations.

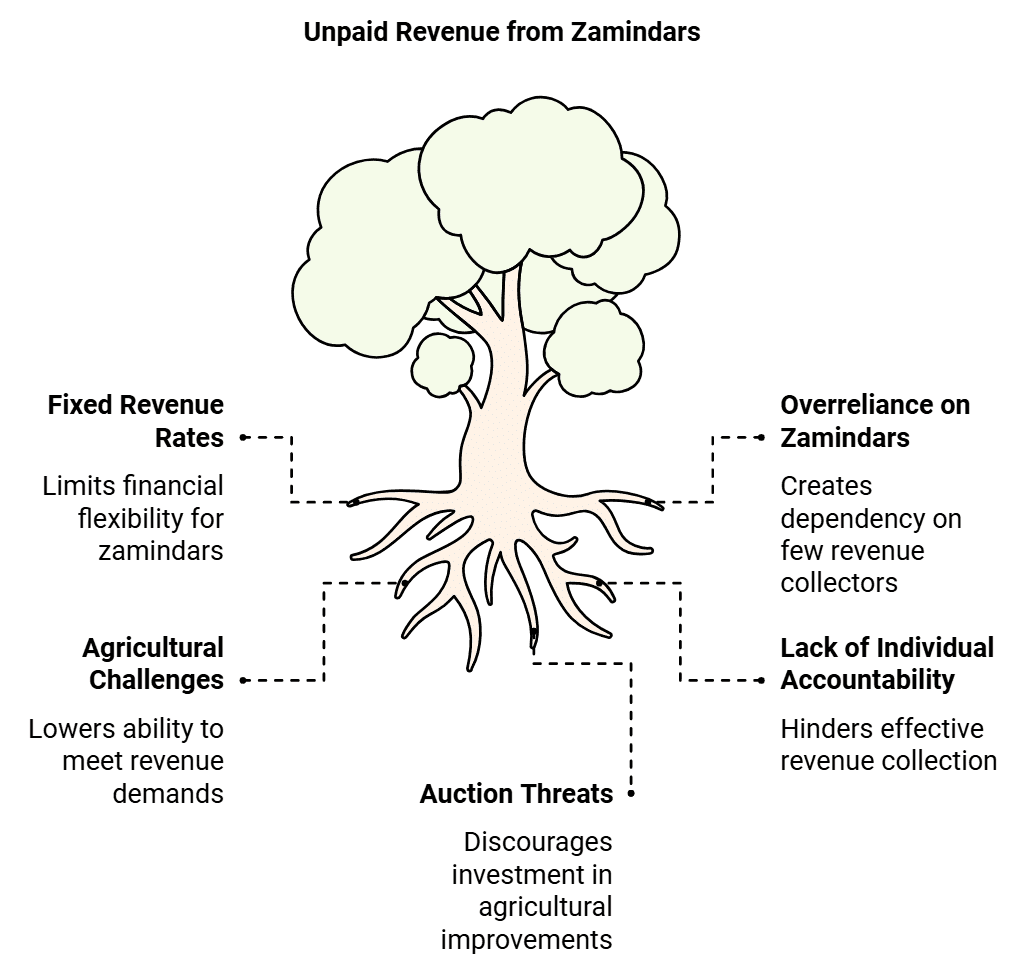

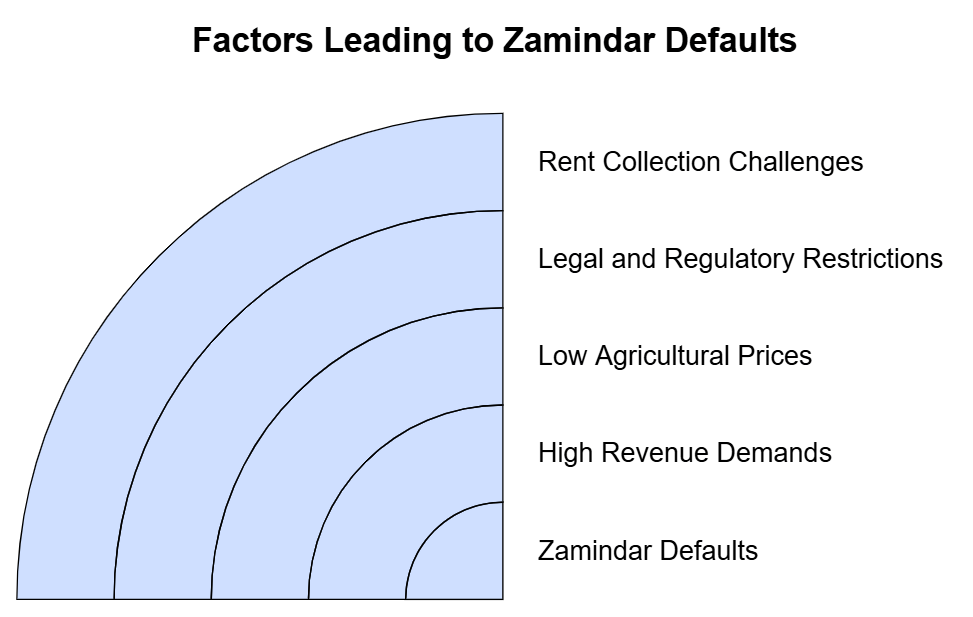

Why Zamindars Defaulted on Payments

- A fixed revenue demand was set to provide zamindars with security and encourage improvements, but high initial demands led to unpaid balances.

- Low agricultural prices in the 1790s made it difficult for ryots to pay dues, affecting zamindars' ability to pay the Company.

- Revenue had to be paid on time regardless of the harvest, risking auctioning of the zamindari under the Sunset Law if unpaid.

- The Permanent Settlement restricted zamindars' power to collect rent and manage estates to control and regulate them.

- Company actions, like breaking up zamindars' troops and abolishing customs duties, limited zamindars' authority and autonomy.

- The collectorate became an important authority, limiting the power of zamindars and taking charge if they didn't pay the revenue.

Rent Collection Challenges

- Rent collection by zamindar representatives, such as amlah, faced perennial challenges, especially during times of bad harvests or low prices.

- Rich ryots and village headmen sometimes intentionally delayed payments, causing difficulties for zamindars asserting their power.

- Defaulters could be prosecuted, but the judicial process was lengthy, leading to a significant number of pending suits for rent arrears in certain regions.

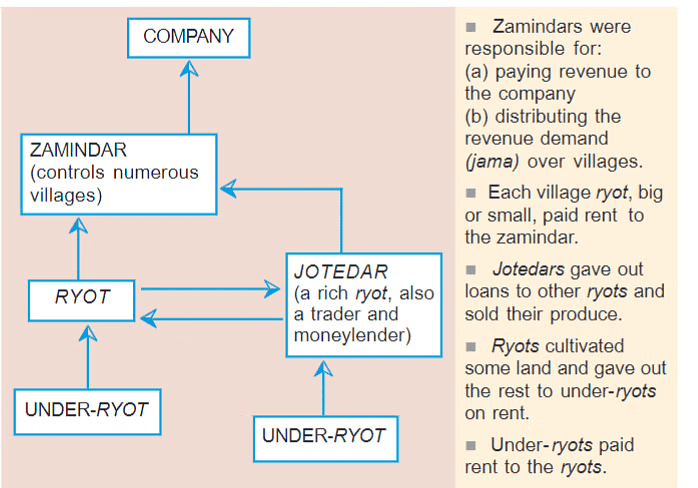

The Rise of the Jotedars

Power in Rural Bengal in Colonial times

Power in Rural Bengal in Colonial times

- Affluent Peasants Consolidating Power: During the late 18th century, affluent peasants began consolidating power in villages while many zamindars faced difficulties.

- Emergence of Jotedars: Francis Buchanan's survey in North Bengal highlighted the rise of prosperous peasants called jotedars.

- Extensive Land Holdings: By the early 19th century, jotedars controlled extensive land holdings, sometimes spanning thousands of acres.

- Control of Trade and Influence: Jotedars controlled local trade, moneylending, and wielded significant influence over poorer cultivators.

- Utilization of Sharecroppers: Jotedars used sharecroppers (adhiyars or bargadars) who worked the land and surrendered half the produce post-harvest.

- Direct Village Control: Unlike urban-residing zamindars, jotedars lived in villages, exerting direct control over the local populace.

- Superior Authority: Jotedars' authority in villages often surpassed that of zamindars, as they impeded zamindars' attempts to increase dues and interfered with officials.

- Mobilization and Revenue Delays: Jotedars mobilized ryots dependent on them and frequently delayed revenue payments to zamindars, sometimes acquiring zamindari estates at auctions.

- Similar Figures in Other Regions: Similar figures such as haoladars, gantidars, or mandals emerged in other parts of Bengal, undermining zamindari authority.

The Zamindars Resist

- Despite challenges, zamindars in rural areas did not lose their authority entirely.

- In response to high revenue demands and the threat of estate auctions, they developed survival strategies.

- New situations led to the creation of innovative approaches.

- Zamindars employed tactics like fake sales to evade revenue demands.

- For example, the Raja of Burdwan transferred part of his zamindari to his mother to protect it from Company takeover.

His agents controlled auctions by holding back revenue demands and collecting unpaid balances.

Zamindar's men would buy the property at auctions, refuse payment, leading to repeated auctions, draining resources of the state and other bidders.

Between 1793 and 1801, major zamindaris in Bengal, such as Burdwan, engaged in benami purchases totaling around Rs 30 lakh.

- At auctions, over 15% of sales were fictitious, illustrating the extent of deceptive transactions.

- Zamindars found ways to prevent being forced off their land. They attacked outsiders buying estates and kept the loyalty of their ryots.

- Peasants viewed zamindars as figures of authority, resisting changes that threatened their identity and pride.

- By the early 19th century, surviving zamindars strengthened their control as the economic downturn of the 1790s ended.

- Flexible revenue payment rules bolstered zamindars' authority over villages.

- It was not until the 1930s Great Depression that zamindars' power weakened, allowing jotedars to gain control in rural areas.

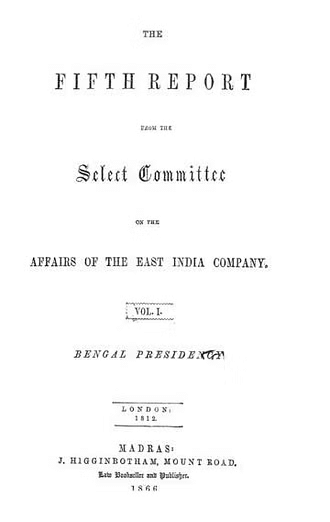

The Fifth Report

- Despite challenges, zamindars in rural areas kept some control by creating strategies to cope with high revenue demands and the risk of losing their estates in auctions.

- Between 1793 and 1801, major zamindaris in Bengal engaged in benami purchases totaling around Rs 30 lakh, with over 15% of auction sales being fictitious.

- Zamindars resisted displacement by attacking outsiders buying estates and maintaining loyalty from ryots, who viewed them as figures of authority.

- By the early 19th century, the surviving zamindars increased their control as the economic troubles of the 1790s came to an end. More flexible rules for paying revenue helped them strengthen their authority over the villages.

- Zamindar power waned during the 1930s Great Depression, allowing jotedars to consolidate control in rural areas.

Fact check: Is the Fifth Report reliable?

- The Fifth Report is very important, but it needs careful reading.

- Understand the author and purpose behind the reports.

- Recent research shows the Fifth Report's arguments and evidence are not entirely reliable.

- Researchers have reviewed Bengal zamindar archives and local district records to study colonial rule in rural Bengal.

- They found that the Fifth Reportexaggerated:

- The decline of zamindari power.

- The extent of zamindar land loss.

- Even during auctions, zamindars often kept their land through clever methods.

The Hoe and the Plough

In the Hills of Rajmahal- In the early 19th century, the Rajmahal hills were inhabited by the Paharias, who practiced shifting cultivation and subsisted on forest produce.

- Conflicts arose as expanding settled agriculture encroached on forest lands, leading to raids by the Paharias on villages for resources.

- Colonial officials attempted to control the Paharias, initially through extermination and later through pacification by giving allowances to Paharia chiefs, though this often led to tensions and resistance.

- Paharia chiefs were given a yearly payment and were responsible for managing their people. They needed to keep order and discipline in their areas. Many chiefs turned down the payment, and those who took it often lost respect and control in their community.

- The British viewed forest dwellers as primitive and aimed to civilize them through settled agriculture, which triggered further conflicts.

- The encroachment of Santhal settlers with plough agriculture led to a symbolic battle between the hoe of the Paharias and the plough of the settlers, representing the struggle between traditional forest-based livelihoods and settled agricultural practices.

Rajmahal Hills

Rajmahal Hills

The Santhals: Pioneer Settlers

- By the end of 1810, Buchanan noted the transformative impact of human labor in the Rajmahal ranges and envisioned the region's potential through cultivation.

- The Santhals, arriving around 1800, displaced the hill folk, cleared forests, and established settlements, initially hired by zamindars and later invited by British officials to settle in the Jangal Mahals.

- Unlike the resistant Paharias, the Santhals proved to be successful settlers, actively engaging in agriculture.

- Given land in the foothills of Rajmahal, the Santhals were designated the Damin-i-Koh region to live, cultivate, and become settled peasants, leading to rapid expansion of Santhal settlements by 1851.

- As the Santhals prospered, the Paharias were marginalized into less fertile terrains, impacting their traditional way of life.

- Facing challenges such as heavy taxes and loss of land control, the Santhals rebelled in the 1850s, leading to the creation of Santhal Pargana, a separate territory established after the Santhal Revolt of 1855-56 to govern them under special laws.

The Accounts of Buchanan

Francis Buchanan

Francis Buchanan

- Buchanan, an employee of the British East India Company, conducted journeys funded by the Company for specific purposes.

- His expeditions had a large group of draughtsmen, surveyors, palanquin bearers, and coolies, with the East India Company covering the costs.

- Buchanan was given instructions on what to seek and document, and his group was recognized as representatives of the government upon arrival at villages.

- The East India Company aimed to expand its influence by identifying and controlling natural resources, dispatching geologists, geographers, botanists, and medical professionals to gather data.

- Buchanan extensively observed geological features, focusing on minerals like iron ore, mica, granite, and saltpetre, and documented local practices such as salt-making and iron ore mining.

- He proposed ways to enhance productivity, often influenced by Western commercial interests, advocating for transforming forests into agricultural lands.

- Buchanan critiqued the lifestyles of forest dwellers, viewing agricultural development as progress.

A Revolt in the Countryside The Bombay Deccan

- Focus shifts to western India, particularly the Bombay Deccan, during a later period to explore rural developments.

- During times of upheaval, peasants express grievances through rebellion, protesting perceived injustices and suffering.

- Understanding the reasons behind their discontent unveils hidden aspects of their lives and experiences.

- Revolts create historical records for examination, prompting authorities to investigate causes and restore peace.

- Throughout the 19th century, peasants across India rebelled against moneylenders and grain dealers.

- An uprising in 1875 in the Deccan region exemplified this resistance.

1875 Deccan Riots

1875 Deccan Riots

Account Books are Burnt

- Occurred in Supa, Poona (present day Pune) district, a prominent market center with many traders and moneylenders.

- The rebellion began on May 12, 1875, when farmers from nearby rural regions targeted shopkeepers, demanding the surrender of their account books and debt documents.

- Actions included burning account books, pillaging grain shops, and sometimes setting fire to the houses of moneylenders.

- The uprising spread from Poona to Ahmednagar, covering a 6,500 square km region within two months.

- Over thirty villages experienced the revolt, marked by attacks on moneylenders, burning account books, and destroying debt bonds.

- Sahukars, fearing peasant reprisals, deserted villages, often abandoning their properties.

- British authorities, noting similarities with the 1857 revolt, set up police posts in villages to prevent peasant uprisings and quickly sent in reinforcements.

- The response led to 951 arrests and numerous convictions, though it took several months to regain control over the countryside.

- The burning of documents and the revolt itself raise questions about the underlying causes and implications.

- This event leads to questions about the Deccan countryside's dynamics and the changes in agriculture under colonial rule. It suggests exploring the broader historical shifts of the nineteenth century.

A New Revenue System

- As British dominion expanded across India, new revenue systems were implemented.

- Initially confined to Bengal due to rising agricultural prices post-1810, which increased Bengal zamindars' incomes under fixed revenue demands.

- Unable to benefit from increased incomes, the colonial government looked for new ways to generate revenue.

- In territories annexed in the 19th century, temporary revenue settlements were started.

- Colonial officials, influenced by economist David Ricardo's ideas, introduced new revenue mechanisms in places like Maharashtra in the 1820s.

- Emphasized taxing landowners on surplus incomes beyond the "average rent" to prevent unproductive use of excess funds.

- In the Bombay Deccan, the ryotwari settlement system was established, directly engaging with ryots for revenue collection, assessing their income capacities, and adjusting rates every 30 years.

- Unlike the Bengal model, the ryotwari system ensured revenue flexibility through regular reassessment and adjustments.

Revenue Demand and Peasant Debt

- In the 1820s, the first revenue settlement in the Bombay Deccan imposed high revenue demands, causing many peasants to abandon their villages and migrate.

- Areas with poor soil and erratic rainfall faced worsened issues. During poor harvests due to failed rains, peasants struggled to meet revenue obligations.

- Revenue collectors, wanting to show their efficiency, used harsh methods such as seizing crops and imposing fines on entire villages.

- By the 1830s, the situation got worse as agricultural prices dropped after 1832 and stayed low for over fifteen years, leading to lower incomes for peasants.

- A severe famine hit the Deccan from 1832 to 1834, causing massive losses of cattle and people and worsening peasants' financial troubles.

- To survive, peasants borrowed money from moneylenders, which became harder to repay.

- Unpaid debts piled up, increasing their dependence on moneylenders and leading to severe indebtedness by the 1840s.

- By the mid-1840s, as signs of economic recovery appeared, British officials eased revenue demands to boost agricultural growth.

- After 1845, with agricultural prices improving, cultivators expanded their farming by acquiring more land, ploughs, and cattle, which led them to take out more loans from moneylenders.

Then Came the Cotton Boom

- Before the 1860s, the majority of raw cotton imports into Britain were sourced from America.

- British cotton manufacturers, concerned about this heavy dependence, sought alternative supply sources.

- In response, the Cotton Supply Association was established in Britain in 1857, followed by the Manchester Cotton Company in 1859, aiming to promote cotton production in globally suitable regions.

- India was identified as a potential alternative supplier due to its fertile soil, favorable climate, and availability of inexpensive labor.

- The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 caused panic in the British cotton industry as raw cotton imports from America plummeted.

- Many efforts were made to increase supplies from India and other regions, resulting in measures to boost cotton cultivation and supply.

- These developments had a profound impact on the Deccan countryside, where farmers suddenly had access to extensive credit.

- Rural farmers were offered advances and long-term loans by sahukars, leading to a significant expansion in cotton production in the Bombay Deccan.

- Between 1860 and 1864, cotton acreage doubled, with over 90% of Britain's cotton imports originating from India by 1862.

- Despite the boom, prosperity was not evenly distributed, and many cotton producers were burdened by heavy debts due to expansion

Credit Dries Up

- During the cotton boom in India, there were ambitions to dominate the global raw cotton market, surpassing the United States.

- In 1861, the editor of the Bombay Gazette speculated on India replacing the Slave States as Lancashire's cotton supplier.

- By 1865, these aspirations faded as the Civil War concluded, leading to a revival of cotton production in America and a decline in Indian cotton exports to Britain.

- Merchants and sahukars in Maharashtra grew hesitant to offer long-term credit due to the falling demand for Indian cotton and falling prices.

- As a result, operations were scaled back, advances to peasants were reduced, and efforts were made to collect outstanding debts.

- With credit sources disappearing, revenue demands jumped sharply during the new settlement, rising by 50 to 100 percent.

- Ryots, dealing with falling prices and shrinking cotton fields, found it hard to meet the increased demands.

- With moneylenders refusing to give loans because they doubted the ryots could repay them, the ryots faced severe financial problems.

American Civil War

American Civil War

The Experience of Injustice

- The ryots were deeply angered by moneylenders refusing to extend loans, not only because of their growing debts and dependence but also because the moneylenders were insensitive to their difficult situation.

- Moneylenders were seen as breaking traditional rules by charging too much interest. Traditionally, interest was not supposed to be more than the amount borrowed.

- Colonial rule saw the breakdown of these norms, with instances like a moneylender charging Rs 2,000 interest on a Rs 100 loan, leading to widespread complaints of injustice.

- The British introduced a Limitation Law in 1859 to limit interest accumulation, but moneylenders found ways to exploit this by forcing ryots to sign new bonds every three years, starting the cycle of debt.

- Moneylenders used dishonest tactics like twisting laws, faking accounts, not giving receipts, inflating bond amounts, and buying peasants' harvests at low prices. Eventually, they seized the peasants' properties.

- Deeds and bonds became symbols of oppression under the British system, as informal agreements were distrusted, and formal contracts became mandatory, even though peasants often didn't understand the terms they were agreeing to.

- Peasants associated their hardships with the new regime of legal documents, feeling compelled to sign documents they didn't comprehend to access loans crucial for their survival.

The Deccan Riots Commission

- During the Deccan revolt, the Government of Bombay initially downplayed its significance.

- The Government of India, concerned about echoes of the 1857 revolt, compelled Bombay to establish an investigative commission.

- The resulting report, known as the Deccan Riots Report, was submitted to the British Parliament in 1878.

- This report serves as a valuable resource for historians, offering diverse source materials on the riot.

- The commission conducted inquiries in affected districts, gathering testimonies from farmers, moneylenders, and witnesses.

- It also compiled and analyzed statistical data on revenue, prices, and interest rates across various regions.

- The commission further examined reports provided by district collectors.

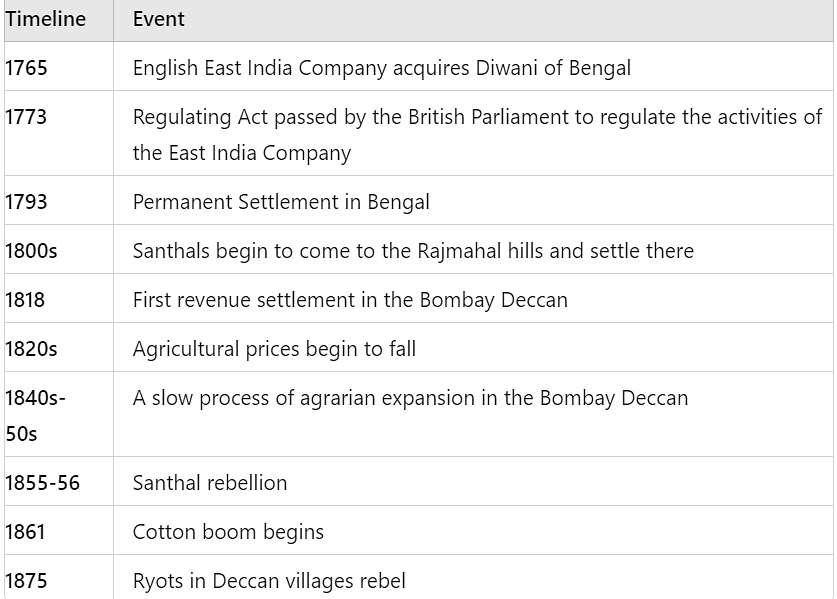

Timeline

Conclusion

The Permanent Settlement significantly impacted Bengal's rural society, leading to displacement and financial strain among zamindars. Affluent peasant classes like the jotedars gained power, shifting the rural power dynamics. These changes in Bengal mirrored broader transformations across India, showcasing the profound effects of colonial policies on India's agrarian landscape.

|

30 videos|342 docs|25 tests

|

FAQs on Colonialism and The Countryside Class 12 History

| 1. What role did the zamindars play in colonial Bengal? |  |

| 2. What were the main causes of the Deccan Riots? |  |

| 3. How did the peasants in Bengal respond to colonial policies? |  |

| 4. What was the significance of the Deccan Riots Commission? |  |

| 5. How did the introduction of colonial agriculture impact rural society in Bengal and the Deccan? |  |