Chola: Local Government | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Local Self-Government under the Cholas |

|

| Mode of Election |

|

| The Scribe |

|

| Adjustment of Chola’s Centralized Administrative Structure |

|

Local Self-Government under the Cholas

The system of village autonomy with assemblies (Sabhas, Urs, and Nagaram) and their committees (Variyams) developed through the ages and reached its culmination during the Chola rule.

Formation and Functions of Village Councils

- Two inscriptions from the time of Parantaka I, discovered at Uttaramerur, detail the formation and functions of village councils.

- The inscription, dated around 920 A.D. during Parantaka Chola’s reign (907-955 A.D.), is a remarkable document in Indian history, serving as a written constitution for the village assembly that operated a thousand years ago.

- Uttaramerur, located in the Kancheepuram district, was established around 750 A.D. by the Pallava king Nandivarman II. It has been ruled successively by the Pallavas, Cholas, Pandyas, Sambuvarayars, Vijayanagara Rayas, and Nayaks.

Historical Significance of Uttaramerur

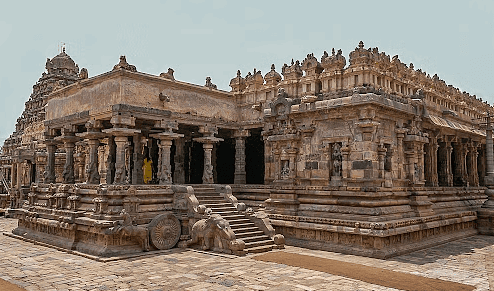

Uttaramerur is noted for its three significant temples:

- Sundara Varadaraja Perumal temple

- Subramanya temple

- Kailasanatha temple

Both Rajendra Chola and Krishnadeva Raya visited Uttaramerur. Built according to agama texts, the village features a central village assembly mandapa, with all temples oriented around it.

Democratic Governance

- While village assemblies likely existed before Parantaka Chola's time, his reign refined village administration into a well-organized system through elections.

- Inscriptions on temple walls across Tamil Nadu mention village assemblies, but Uttaramerur contains the earliest inscriptions detailing the functioning of elected village assemblies.

- The Uttaramerur inscriptions illustrate a democratic government at the village level, outlining how the village assembly was composed of elected members.

Details from the Inscriptions

The inscriptions provide remarkable details about the:

- Constitution of wards

- Qualifications for candidates

- Disqualification criteria

- Election procedures

- Formation and functions of committees

- Powers to remove wrongdoers

Secular transactions related to administration, judiciary, commerce, agriculture, transportation, and irrigation regulations, managed by the village assembly, are inscribed on the mandapa walls, showcasing efficient village administration from ancient times.

Right to Recall and Election Process

- Villagers had the right to recall elected representatives for failing their duties. The entire village, including infants, was required to be present at the mandapa during elections, with exemptions for the sick and those on pilgrimages.

- Various committees were responsible for maintaining irrigation tanks, roads, providing drought relief, testing gold, and other tasks.

- Members were chosen annually for committees like the Annual Committee, Garden Committee, Tank Committee, and Gold Committee.

- The local assembly oversaw tasks such as temple maintenance, agriculture, irrigation, tax collection, and road construction through these committees.

- The Chola Emperors respected the decisions made by these assemblies.

Constitution for Elections

The village assembly of Uttaramerur drafted the constitution for elections, which included the following features:

- The village was divided into 30 wards, with one representative elected from each ward.

- Qualifications and disqualifications were specified for candidates.

Qualifications for Candidates

- Ownership of Land: Candidates must own more than a quarter of a veli(a unit of land) of tax-paying land.

- Residential Requirement: Candidates must live in a house built on their own site.

- Age Limit: Candidates must be between 35 and 70 years old.

- Educational Requirement: Candidates must know the Mantrabrahmana by teaching it to others. If they own only one-eighth of a veli, they must have learned one Veda and one of the four bhasyas by explaining it to others.

- Character and Experience: Candidates must be virtuous, well-versed in business, and honest, with no committee service in the last three years.

Disqualifications

Certain individuals and their relatives were disqualified from candidacy, including:

- Those who failed to submit accounts while serving on committees.

- Relatives such as sons, fathers, brothers, sons-in-law, fathers-in-law, uncles, and sisters-in-law.

- Individuals guilty of serious sins or incest.

- Those who committed theft, consumed forbidden foods, or committed sins and became pure through expiation.

The specified individuals could not have their names entered for committee candidacy for life.

Mode of Election

- Names for pot-tickets will be written for each of the thirty wards, and separate covering tickets will be prepared for each ward in the twelve streets of Uttaramerur.

- These packets will be bundled separately and placed into a pot.

- When it is time to draw the pot-tickets, a full meeting of the Great Assembly, including all members, young and old, will be convened.

- All temple priests (Numbimar) present in the village on that day will be seated in the inner hall where the assembly meets.

- Among the priests, the eldest will stand up and lift the pot, showing it to the assembly.

- A young boy, unaware of the contents, will draw a packet representing one ward from the pot, transfer it to another empty pot, and shake it.

- From this pot, the boy will draw one ticket and hand it to the arbitrator (madhyastha).

- The arbitrator will receive the ticket with an open palm, read the name on it, and the priests will also repeat the name.

- The name read by the arbitrator will be accepted as the chosen representative for that ward.

- This process will be repeated for each of the thirty wards.

Constitution of the Committee:

- Of the thirty men chosen, those who have previously served on the Garden and Tank committees, along with those advanced in learning and age, will be selected for the Annual Committee.

- From the remaining members, twelve will be chosen for the Garden committee and six for the Tank committee. These selections will also be made by drawing pot-tickets.

Duration of the Committees:

- The members of the three committees will hold office for three hundred and sixty days and then retire.

Removal of Persons:

- If a committee member is found guilty of an offense, they will be removed immediately.

- The remaining committee members, with the help of the Arbitrator, will convene an assembly to appoint new members by drawing pot-tickets, following the established order.

Pancavara and Gold Committees:

- For the Pancavara and Gold committees, names will be written for pot-tickets in the thirty wards.

- Thirty packets will be deposited in a pot, and pot-tickets will be drawn as previously described.

- From the thirty tickets drawn, twenty-four will be for the Gold committee and six for the Pancavara committee.

- When drawing pot-tickets for these committees in the following year, wards already represented in the current year will be excluded.

- Individuals who have ridden on an ass or committed forgery will be ineligible.

Qualification of the Accountant:

- An Arbitrator with honest earnings will be responsible for writing the village accounts.

- No accountant can be reappointed until they submit their accounts for the period of their office to the big committee, and are declared honest.

- Accounts written by an accountant must be submitted by them personally, and no other accountant can close their accounts.

King’s Order:

- Committees shall always be appointed by pot-tickets as long as the moon and sun endure.

- This practice is based on the royal letter issued by the emperor, Parakesarivarman, who is fond of learned men and whose acts resemble those of the celestial tree.

Officer Present:

- A representative from the Chola emperor was present while writing the constitution, facilitating this settlement.

Villager’s Decision:

- The assembly members of Uttaramerur Caturvedimangalam made this settlement for the village's prosperity, aiming to ensure the downfall of wicked men and the well-being of the rest.

The Scribe

- At the order of the assembly's great men, the Arbitrator wrote this settlement.

- Each assembly operated independently according to its constitution, addressing local issues. For matters affecting multiple assemblies, decisions were made collectively.

- Local government provided a platform for the population to express grievances and resolve issues, reinforcing the democratic aspects of village assemblies.

- However, Chola village assemblies exhibited only some democratic practices, as the Chola polity was an absolute monarchy.

- The central government maintained general oversight and could intervene in village matters during emergencies.

- Village assemblies had to consider central government policies, and some Brahmana Sabhas were closely linked to the Chola court.

- Uttaramerur inscriptions indicate that the Sabha's resolution was made in the presence of a royal official.

- Tanjavur inscriptions show that Raja Raja I instructed the Sabha of Cholamandalam to perform various services in the Brihadeshwara temple.

- Other indicators of limited democracy included the election of candidates by lot rather than voting, and differing membership criteria for Ur and Sabha assemblies.

- The Nagaram, composed of traders, managed market centers and regulated commerce.

- Certain individuals were barred from contesting elections, and there is no evidence of quorum or voting in assembly decisions.

- Water supplies significantly influenced which villages had assemblies and which did not.

- Villages in the central Kaveri river basin were under direct Royal control, while those in drier regions were autonomous with self-governing institutions.

- Thus, village assemblies cannot be deemed democratic in the modern sense, as grassroots democracy was not absolute.

Adjustment of Chola’s Centralized Administrative Structure

- The Chola Emperors generally respected the decisions of local assemblies, which operated autonomously based on their constitutions and customs, addressing local issues independently.

- In cases affecting multiple assemblies, decisions were reached through mutual deliberation.

- The central government retained general oversight and the right to intervene in village matters during emergencies, while local assemblies had to align with central government policies.

- Some Brahmana Sabhas had close ties with the Chola court, as evidenced in Uttaramerur inscriptions, where royal officials were present during Sabha resolutions.

- Tanjavur inscriptions reveal that Raja Raja I directed the Sabha of Cholamandalam to carry out various services in the Brihadeshwara temple.

- Important brahmadeyas were granted taniyur status, allowing them considerable functional autonomy as independent entities.

- Central region villages in the Kaveri river basin were placed under direct Royal control, while more distant and drier regions enjoyed autonomy with self-governing institutions.

- Local assemblies like Nagaram acted as agents of the monarchy in regulating trade and markets.

- Revenue assessment and collection were managed by local assemblies such as Ur, Sabha, and Nagaram, with revenue passed on to the central government.

- Local administration through assembly units alleviated the central government’s burden, allowing populations to voice grievances and resolve issues, thereby minimizing opposition and reinforcing state stability.

|

367 videos|995 docs

|

FAQs on Chola: Local Government - History Optional for UPSC

| 1. What was the structure of local self-government under the Chola dynasty? |  |

| 2. How were elections conducted for local self-government in the Chola period? |  |

| 3. What role did scribes play in the local administration during the Chola dynasty? |  |

| 4. How did the Chola dynasty's centralized administration influence local governance? |  |

| 5. What were the key features of the Chola local government system that contributed to its effectiveness? |  |