Economy: Agricultural Production | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Distribution of revenue resources |

|

| Land Revenue and its extraction |

|

| Agricultural Production |

|

| Agrarian Relation |

|

| Agriculture technology during Sultanate |

|

Introduction

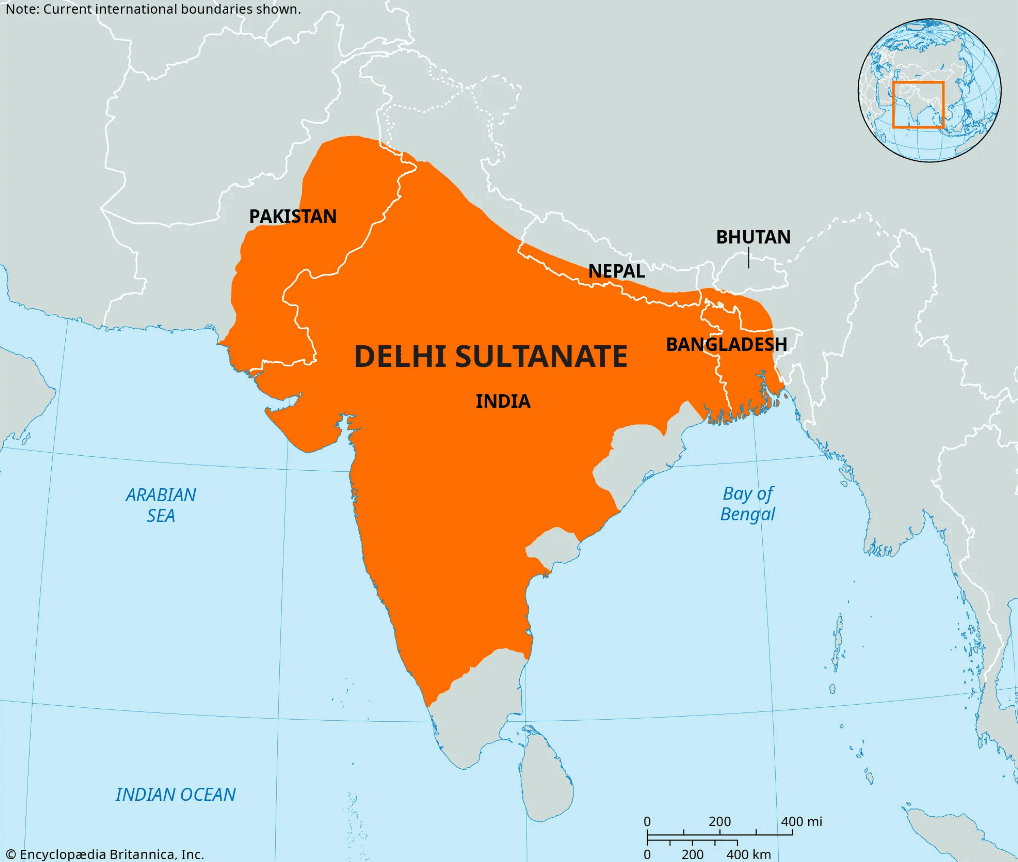

The Ghorids' Conquest and the Delhi Sultanate: Economic Transformations in Northern India:

- The conquest of Northern India by the Ghorids and the establishment of the Delhi Sultanate brought significant changes to the political and economic landscape of the region.

Tax Collection and Coinage:

- The conquerors introduced well-defined systems for tax collection, distribution, and coinage.

- However, the existing systems could not be completely overhauled immediately.

Superimposition and Gradual Change:

- Initially, the new systems were superimposed on the older ones.

- Modifications and changes were gradually introduced by different Sultans up to the late 15th century.

Opinions of Historians

Muhammad Habib:

- Believed that the economic changes brought by the Delhi Sultanate created a far superior organization compared to the previous one.

- Felt that the changes were so significant that they warranted the terms ‘Urban Revolution’ and ‘Rural Revolution’.

D. Kosambi:

- Acknowledged that the Islamic raiders broke down rigid customs in the adoption and transmission of new techniques.

- However, he viewed the changes as merely intensifying elements already present in Indian feudalism.

Distribution of revenue resources

Payment to Soldiers and Tax Collection:

- Soldiers were paid their salaries in cash, unlike previous rulers.

- Regions that refused to pay land-tax or kharaj were known as mawas and were subjected to plunder or military raids.

- A mechanism for simultaneous revenue collection and distribution was gradually introduced.

Iqta System:

- The new rulers introduced the iqta system, which combined revenue collection and distribution without threatening political unity.

- The iqta was a territorial assignment, and its holder, known as the muqti or wali, was responsible for collecting taxes on behalf of the Sultan.

- Nizam-ul Mulk Tusi, a Seljuq statesman, defined the iqta system as a revenue assignment held by the muqti at the Sultan's pleasure.

- The muqti was entitled to collect land tax and other taxes but had no claims on the personal possessions of the cultivators.

- The muqti had obligations to the Sultan, including maintaining troops.

- Transfers of iqtas were common, and the iqta was a transferable charge.

Khalisa:

- Khalisa referred to territory whose revenues were directly collected for the Sultan’s treasury.

- The size of the khalisa expanded under Alauddin Khalji but did not consist of shifting territories.

- Delhi and its surrounding districts, including parts of Doab, likely remained in khalisa.

- In Iltutmish’s time, Tabarhinda (Bhatinda) was also in khalisa.

- Under Alauddin Khalji, the khalisa covered the whole of middle Doab and parts of Rohilkhand, but during Feroz Tughluq’s reign, it likely reduced in size.

Differentiating Factors of Iqta System:

- Iltutmish (1210-36) assigned small iqtas in the Doab to soldiers as salaries.

- Balban (1266-86) attempted to resume iqtas unsuccessfully.

- Alauddin Khalji (1296-1316) firmly established cash payment of salaries to soldiers.

- Feroz Tughluq changed the practice by assigning villages to soldiers as salaries, known as wajh, making them permanent and hereditary.

Administration of Iqta System:

- In the early years of the Sultanate, the revenue income from iqtas was unknown, and the size of the contingent was not fixed.

- Balban(1266-86) introduced some central control by appointing a khwaja(accountant) with each muqti to monitor income and expenditure.

- Alauddin Khalji strengthened iqta administration with a central finance department (diwan-i wizarat) estimating revenue income from each iqta.

- Enhancements in estimated revenue income were common, and punishments for discrepancies were severe.

- Ghiyasuddin Tughluq(1320-25) introduced moderation, limiting enhancements to 1/10 annually.

- Muqtis were allowed to keep 1/10th to 1/20th in excess of their sanctioned salaries.

Land Grants:

- Religious persons and institutions such as dargahs,mosques,madrasas, and dependents of the ruling class were maintained through revenue grants called milk,idrar, and inam.

- These grants were generally not resumed or transferred, though the Sultan had the right to cancel them.

- Alauddin Khalji and Ghiyasuddin Tughluq cancelled many grants, while Feroz Tughluq returned all previously resumed grants and made new ones.

- Despite this generosity, grants accounted for only about one-twentieth of the total jama(estimated revenue income).

- Nobles also made revenue grants from their own iqtas, and Sultans made grants in both khalisa and iqtas, covering cultivated and cultivable areas.

Land Revenue and its extraction

Before the Arrival of the Turks:

- According to the Dharamashastras, peasants traditionally paid one-sixth of the produce as their share. However, some kings in South India were known to demand one-third or even two-thirds of the produce. For instance, a Chola king allowed his feudatories to collect half of the produce.

- During the 13th century, there was little change in the structure of rural society.

- The early Turkish rulers relied on Hindu chiefs to collect land-revenue from peasants, following existing practices.

- Barani described the Turkish ruling class’s approach: Balban advised his son Bughra Khan to strike a balance in land-revenue (kharaj) to avoid making peasants too poor or too wealthy.

- The Turkish rulers were familiar with the Islamic land tax known as kharaj, which was a share in the produce rather than a rent on the land.

- In the 13th century, kharaj took the form of tribute, paid either by former potentates or through plundering raids in rebellious areas, often in the form of cattle and slaves.

- Before Alauddin Khalji, there was no serious effort to systematize the assessment and collection of kharaj.

Agrarian Measures of Alauddin Khalji:

- Alauddin Khalji aimed to increase revenue collection by raising the demand, implementing direct collection, and minimizing leakages to intermediaries.

- He raised land-revenue demand to half in the upper Doab region and certain areas of Rajasthan and Malwa, designating these areas as khalisa, where revenue went directly to the Imperial treasury.

- Land-revenue demand was based on the measurement of cultivated area.

- While the demand was fixed in kind, realization was mostly in cash. Outside Delhi, cultivators were encouraged to pay in cash.

- Barani noted that revenue collectors were instructed to demand revenue rigorously, forcing peasants to sell their produce immediately.

- Alauddin aimed to ensure that cultivators sold their grains to banjaras before transporting them to their own stores.

- His measures significantly intervened in village affairs, targeting privileged sections like khuts,muqaddams, and chaudhuris, as well as rich peasants with surplus food grains.

- Attempts to eliminate the privileges of khuts and muqaddams and appoint corrupt amil supervisors for revenue collection were largely unsuccessful.

- Alauddin’s revenue measures collapsed after his death, leading to the restoration of privileges for khuts and muqaddams.

- Ghiyasuddin Tughlaq replaced the measurement system in khalisa areas with sharing, providing relief to cultivators by sharing both profit and loss.

- He also ordered gradual revenue demand increases in iqta territories, avoiding sudden enhancements to prevent ruin and promote prosperity.

- Muhammad Tughlaq attempted to revive and expand Alauddin’s system, but his measures sparked peasant uprisings due to harsh assessments and official price applications.

- His policies, like Alauddin’s, aimed to curtail the privileges of khuts and muqaddams, but also adversely affected average cultivators.

- Tughlaq later shifted focus in khalisa areas, promoting better cultivation through changing cropping patterns and granting loans for improvements.

- Firuz Tughlaq’s rule is noted for rural prosperity, with widespread tillage and canal systems extending cultivation.

- Firuz improved water access in Haryana, allowing peasants to cultivate according to their preferences.

- Overall, land-revenue under the Sultans, especially in the 14th century, remained high, around half, with efforts to reduce the power of old intermediaries.

- Despite heavy land-revenue, there was some success in improving the rural economy, although benefits largely accrued to privileged sections.

Agricultural Production

Continuity and Change in Agriculture During the Sultanate Period:

- The Sultanate period did not bring significant changes to the system of agricultural production.

- However, the introduction of new technologies appears to have improved irrigation practices.

- There was also the spread of certain market crops like indigo and grapes.

- In the 13th to 14th century, the land-to-man ratio was very favorable.

- Peasants had more land per person due to a much smaller population.

- Despite this, social constraints led to the presence of landless laborers and menials in villages.

- Forests were more extensive, and there was an abundance of cultivable land yet to be brought under plough.

- Pasturage facilities for cattle were also good, indicating extensive agriculture.

- Control over land was less important than control over the people cultivating it.

- Sufi Nizamuddin Aulia in the 13th century noted the presence of tigers harassing wayfarers between Delhi and Badaun.

- The author of Masalik al Absar observed that cattle in India were numerous and inexpensive.

- Atif noted that no village in the Doab was without a cattle-pen (Kharaks).

- A large area of even fertile land was covered by forests and grassland.

- It was only by the end of Akbar’s reign (1605) that the middle Doab was reported to be fully cultivated.

Crops and other Agricultural Produce

Large Number of Crops in the Delhi Sultanate:

- Peasants in the Delhi Sultanate grew a wide variety of crops, possibly unmatched in other parts of the world, except maybe in South China.

- Ibn Battutah, a traveler who explored India, documented the numerous food grains, crops, fruits, and flowers produced in the region. He noted the fertility of the soil, which allowed for the cultivation of two crops a year, including the familiar rabi (winter) and kharif (monsoon) crops. In some cases, like rice, it was sown three times a year.

- Thakkur Pheru, a mint-master in Delhi during the reign of Alauddin Khalji, listed around twenty-five crops grown under two harvests, providing insights into the agricultural practices of the time.

- Food crops mentioned include wheat,barley,paddy,millets(jowar, moth, etc.), and various pulses (mash, mung, lentils, etc.). Cash crops included sugarcane,cotton,oil-seeds(sesame, linseed, etc.).

- The introduction of improved irrigation facilities contributed to the expansion of rabi (winter) crops such as wheat and sugarcane.

- Crops also supported village industries, including oil processing,jaggery production,indigo dyeing,spinning, and weaving. Barani's account highlights the emergence of a new rural industry producing wine from sugarcane by the 14th century, particularly around Delhi and in the Doab region.

- Indigo, although not mentioned by Thakkur Pheru, became a significant export item to Persia. The use of lime-mortar in indigo vats likely improved dye production.

- Crops like potato,maize,red chillies, and tobacco, introduced in the 16th century, were not present during this period.

Development of Gardens and Fruit Cultivation:

- During the 14th century, under Muhammad bin Tughlaq and Firuz Tughlaq, there was significant development of gardens. Firuz Tughlaq is said to have established 1200 gardens around Delhi, improving the cultivation of fruits, particularly grapes.

- Wine, especially grape-wine, began to be produced in Meerut and Aligarh, with other regions like Dholpur,Gwalior, and Jodhpur adopting improved methods of fruit cultivation. Jodhpur became known for its superior pomegranates, with Sikandar Lodi claiming that Jodhpur's pomegranates surpassed those from Persia in flavor.

- While these orchards primarily catered to the wealthy, they also contributed to employment and trade. Ibn Battuta's account indicates that the technique of grafting was not known among peasants at the time.

- Grapes were initially grown only in limited areas, but under Feroz Tughlaq, the establishment of 1200 orchards around Delhi led to an abundance of grapes, causing prices to drop.

- Sericulture(silk production) was not practiced by Indian peasants during this period. True silk was not produced; only wild and semi-wild silks like tassar,eri, and muga were known. The first reference to sericulture in Bengal was made by Ma Huan, a Chinese navigator, in 1432.

Canal Irrigation and Its Impact:

- Agriculture during this period largely relied on natural irrigation through rains and floods, leading to a preference for single rain-fed kharif (autumn) crops and coarse grains.

- Canal irrigation was documented in historical sources, with the Delhi Sultans themselves undertaking canal construction for irrigation purposes.

- Ghiyasuddin Tughluq(1320-25) was the first Sultan to dig canals, but Feroz Tughluq(1351-88) significantly expanded canal irrigation by cutting canals from the Yamuna,Sutlej, and Ghaggar rivers.

- Feroz Tughluq's canal network was the largest in India until the 19th century, greatly aiding the extension of cultivation in eastern Punjab and promoting the growth of cash crops like sugarcane.

- A stretch of about 80 krohs (200 miles) of land was irrigated by the canals Rajabwah and Ulughkhani, allowing peasants in eastern Punjab to raise two harvests (kharif and rabi) where only one was possible earlier.

- New agricultural settlements emerged along the banks of the canals, with 52 colonies springing up in the irrigated areas. Afif noted that no village remained desolate and no land uncultivated.

- Regarding agricultural implements, there were no significant changes until the 19th century. Most land remained rain-fed, although digging wells and constructing bunds(embankments) for water storage were considered virtuous acts, with the state actively involved in their construction and maintenance.

- The productivity of the soil may have been enhanced by more extensive manuring with cattle, which were abundant. The importance of cattle was reflected in the agricultural tax based on the number of animals, and banjaras(nomadic traders) had thousands of oxen for their journeys.

Agrarian Relation

Agrarian Relations in India: A Historical Overview:

- D. Kosambi: Believed the changes intensified existing elements of Indian ‘feudalism’.

- Irfan Habib: Regarded the changes as radical and progressive, deserving the term 'rural revolution.'

- Minhaj Siraj: Described chiefs opposing the Ghorians and early Delhi Sultans as 'rai' and 'rana,' with their cavalry commanders as 'rawat.'

- Epigraphic evidence from Northern India establishes the feudal hierarchy of raja (rai), ranaka (rana), and rauta (rawat).

- In the early phase, the Sultans often settled with the defeated rural aristocracy, imposing kharaj(tribute) upon them.

- Even after Alauddin Khalji's tax reforms, the older rural aristocracy still played a role in revenue collection.

- Afif's Account: Describes Ghazi Malik pressuring Rana Mal Bhatti for revenue collection, indicating the subjugated aristocracy’s responsibility in land revenue.

- Peasant Economy: Characterized by individual peasant farming with varying land sizes. Noted extremes between khots and muqaddams with large holdings and balahar with minimal land.

- Presence of landless laborers in later sources, but not in contemporary accounts.

- No proprietary rights for peasants over land or produce; claims by superior classes.

- Freedom of Peasants: Though considered 'free born,' peasants lacked the ability to leave land or change domicile at will.

- Village Structure: Each village had 200-300 male members with a patwari for account-keeping. The bahi(account register) was crucial for tracking payments by peasants to revenue officials.

- The patwari was a village official, not a government appointee, suggesting the village was an administrative unit outside Sultanate control.

- The village community, despite Alauddin Khalji's efforts to tax individual peasants, remained a unit of land revenue payment.

- Rural Intermediaries: Including khot,muqaddam, and chaudhuri, these intermediaries were the upper stratum of peasantry.

- Chaudhuri: Emerging in the 14th century, defined by Ibn Battuta as the chief of a group of villages.

- Village Headmen: Initially prosperous, they faced revenue imposition by Alauddin Khalji but were essential for land revenue collection.

- Ghiyasuddin Tughluq: Moderated policies against rural intermediaries, restoring some privileges.

- Feroz Tughluq: Further strengthened rural intermediaries, leading to their designation as zamindars.

Agriculture technology during Sultanate

Technological Devices in Agriculture

Plough:

- The plough, as depicted in the Persian lexicon "Miftah-ul Fuzala" (circa A.D. 1460), featured an iron share and was drawn by two yoked oxen.

- During the Iron Age, the Aryan settlement in the Gangetic plain led to the development of the plough where the ploughshare/cutter was made of iron, enhancing its effectiveness in tilling harder soils.

- Kalibangan, an Indus Valley site in Rajasthan, is noted for the use of an 'ironless plough.'

Sowing:

- Broadcasting was a known method of sowing seeds.

- Seed-drill: Used for sowing seeds, mentioned by Barbosa (circa 1510) in the context of wet-cultivation of rice.

Harvesting, Threshing, and Winnowing:

- Harvesting was done using a sickle.

- Threshing was performed using oxen.

- Winnowing involved the use of wind power.

Irrigation Devices:

- Rainwater, ponds, and tanks were sources of irrigation.

- Wells were the most important controlled source of irrigation, especially in North India.

- Wells were typically masonry with raised walls, and platforms, although kuchcha wells existed but were less durable.

Techniques to Raise Water from Wells:

- Rope-bucket technique: A simple method of drawing water using a rope and bucket by hand.

- Rope-bucket-pulley technique: Used pulleys to reduce human effort.

- Ox-powered rope-bucket-pulley: Replaced human power with oxen.

- Shaduf (tula/dhenkli): A semi-mechanical device using the first-class lever principle to lift water.

- Saqiya or Persian Wheel: Advanced waterwheel with a gear system, evolved from earlier forms like Araghatta and Ghatiyantra.

Shovel, Pick-axe, and Scraper: Various implements used in agricultural and gardening processes.

|

367 videos|995 docs

|