Free Radicals | Chemistry Optional Notes for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Free Radicals |

|

| Types of Free Radicals |

|

| Structure of Free Radicals |

|

| Free Radical Mechanisms |

|

| Free Radical Reactions |

|

| Stability of Free Radicals |

|

| Uses of Free Radicals |

|

Introduction

Any molecular species that have an unpaired electron in an atomic orbital and is capable of independent existence is referred to as a free radical. Most free radicals exhibit certain similar characteristics when an unpaired electron is present. They are highly reactive and inherently unstable. Hence, they can act as oxidants or reductants by either giving or receiving an electron from other molecules.

In various disease conditions, the hydroxyl radical, superoxide anion radical, hydrogen peroxide, oxygen singlet, hypochlorite, nitric oxide radical, and peroxynitrite radical are the most significant oxygen-containing free radicals causing metabolic problems.

Free Radicals

In Chemistry, a molecule with at least one unpaired electron in its outer shell is referred to as a free radical. The majority of molecules have an even number of electrons, and the covalent chemical bonds that hold the atoms in a molecule together often comprise pairs of electrons shared in a bond.

Most radicals are thought to have formed by the cleavage of typical electron-pair bonds, with each cleavage resulting in two distinct entities that both have one unpaired electron from the broken bond along with the rest of the paired electrons.

Free radicals are produced via the homolytic bond fission process. These are extremely reactive compounds with odd electron configurations. Due to the presence of unpaired electrons, free radicals are paramagnetic which implies that they have a small permanent magnetic moment. The presence of free radicals can be determined using this paramagnetic behaviour of any compound or molecule.

Free radicals are extremely reactive, which allows them to remove electrons from other compounds in order to attain stability. Thus, the attacked molecule loses its electron and transforms into a free radical, starting a cascade of events or chain reactions. Hydroxyl radical (OH∙) is the most common example of a free radical. The triplet oxygen and triplet carbene are examples of free radicals with two unpaired electrons.

Types of Free Radicals

There are mainly two types of free radicals that exist in nature:

- Neutral Radicals

- Charged Radicals

Neutral Radicals

These radicals do not contain any charge on the central atom and are found to be less reactive than the other types. For example, methyl radical, butyl radical, hydroxyl radical, superoxide radical, etc.

Charged Radicals

The entire compound is positively or negatively charged in charged free radicals. These are found to be highly reactive that can easily react or combine with other compounds or elements.

Structure of Free Radicals

The structure of free radicals varies with the central atom. For example, the geometry of an alkyl halide shows a planar shape with sp2 hybridization.

A carbon atom with three bonds and one unpaired electron is called an organic free radical.

Free radicals with carbon that has an unpaired electron may also be in an sp2 hybridised state, in which case the structure is planar and has an odd electron in the p orbital, or it may be sp3 hybridised, in which case the structure may be pyramidal.

An unpaired single electron in an unhybridized p-orbital with trigonal pyramidal or planar geometry and an angle of 120 degrees is sp2 hybridised with a carbon radical.

Free Radical Mechanisms

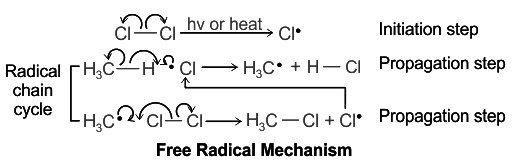

The free radical reactions are chain reactions. The mechanism of such reactions completes in three simple steps. Let us discuss them by taking the chlorination of methane as an example.

Step 1. Initiation

This step begins with the splitting of one of the reactant molecules. In the example of methane chlorination, homolysis of chlorine takes place at initiation resulting in the formation of a neutral chlorine free radical. The splitting is done in the presence of heat or light.

Step 2. Propagation

The “chain” component of chain reactions is described in the propagation phase. Once a reactive free radical is created, it can combine with other stable molecules to create further reactive free radicals. These fresh free radicals then produce yet more radicals, and so forth. Hydrogen abstraction or the insertion of radicals to double bonds are frequent propagation processes.

In the chlorination of methane, a primary methyl radical is produced once the hydrogen atom is removed from methane. The chlorine atom is then drawn away by the methyl radical, producing chlorine-free radicals.

Step 3. Termination

When two free radical species combine to produce a stable, non-radical adduct, chain termination takes place. The low concentration of radical species and the minimal possibility of two radicals interacting with one another make this occurrence. In other words, the reaction has a very high Gibbs free energy barrier, primarily because of entropic rather than enthalpic factors.

Free Radical Reactions

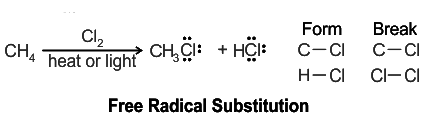

In organic chemistry, several free radical reactions take place including free radical substitution, addition, elimination, etc. The most common reaction observed is the halogenation of alkanes which results in the formation of a mixture of isomers.

Stability of Free Radicals

Stability of free radicals can be explained with the help of the inductive effect, hyperconjugation, and resonance effect.

Inductive Effect: The stability of the radical will increase as the number of alkyl groups connected to the free radical carbon core increases. The reason behind this is the alkyl group electron-donating inductive effect, which reduces the radical’s electron deficit.

Hyperconjugation: Similar to how carbocations are stabilized by the hyperconjugation effect, free radicals are also stabilized in the same way. Alkyl free radicals are stable in the following order: tertiary > secondary > primary > CH3. Hyperconjugation is capable of explaining this stability order. Through hyperconjugation, the odd electron in the alkyl radical is delocalized onto the beta-hydrogens, giving the radical its stability. Consequently, the tert-butyl radical is more stable than the sec-butyl radical, which is more stable than the n-butyl radical.

Resonance: The resonance effect results in the stability of free radicals where the carbon centre is conjugated to a double bond. Resonance provides a satisfactory explanation for the stabilizing effects of vinyl groups (in allyl radicals) and phenyl groups (in benzyl radicals), which are both quite significant. Although allyl and benzyl free radicals are more stable than alkyl free radicals, they only persist briefly under normal circumstances.

Properties of Free Radicals

Reactivity: Free radicals contain an unpaired electron in their orbital. In order to gain stability, they combine aggressively with other compounds which indicates their high reactivity.

Instability: Free radicals are highly unstable species due to the presence of an unpaired electron that wants to get paired immediately to achieve stability.

Uses of Free Radicals

- Industrially, they are used mainly in polymerization reactions.Alkyl halides or aryl halides are also used as precursors in several halogenation reactions.In normal conditions inside the body, they help to fight different pathogens by damaging their cell wall or affecting the various metabolic processes.

Effects of Free Radicals

Oxidative stress is a condition brought on by the presence of free radicals in the body. Since oxygen is present throughout the chemical processes that allow free radicals to receive an electron, they are known as “stress” reactions. Free radicals are unstable atoms that are produced naturally during metabolism or as a result of exposure to toxins in the environment.

In excess, free radicals can harm cells, bring on illnesses, and hasten the ageing process. The hydroxyl radical and superoxide are the two most significant oxygen-centred free radicals. In reducing environments, they originate from molecular oxygen. These same free radicals can, however, take part in unintended side reactions that cause cell harm due to their reactivity. These free radicals can damage and kill cells in excess amounts.

FAQs on Free Radicals - Chemistry Optional Notes for UPSC

| 1. What are free radicals? |  |

| 2. What are the types of free radicals? |  |

| 3. How are free radicals structured? |  |

| 4. What are the mechanisms of free radicals? |  |

| 5. How do free radical reactions occur? |  |

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|