Laxmikant Summary: Landmark Judgements and Their Impact- 1 | Indian Polity for UPSC CSE PDF Download

1. Romesh Thappar Case (1950)

- Name of the Case: Romesh Thappar vs. State of Madras

- Year of Judgement: 1950

- Popular Name: Cross Roads case

- Related Topic/Issue: Freedom of the press

- Related Article: Article 19

Supreme Court Judgement

It held that the freedom of speech and expression under Article 19(1)(a) includes freedom of propagation of ideas. This freedom is ensured by the freedom of circulation. The Madras government's order banning the entry and circulation of the weekly English Journal Cross Roads published at Bombay was declared unconstitutional and void. The ban was issued under Section 9(1-A) of the Madras Maintenance of Public Order Act, 1949. The Supreme Court emphasized that freedom of speech and the press is foundational for democratic organizations and public education.

Impact of the Judgement

As a consequence of this judgement, the 1st Amendment Act (1951) added "public order" as a reasonable restriction under Article 19(2) on the freedom of speech and expression. The Supreme Court clarified that restrictions on freedom could only be imposed based on the grounds mentioned in Article 19(2). The court rejected restrictions on the ground of public order, stating that ordinary or local breaches of public order were not valid grounds for limiting freedom of speech and expression. The term "public order" was interpreted to signify the state of tranquility resulting from internal regulations enforced by the government within the political society.

2. A.K. Gopalan Case (1950)

- Name of the Case: A.K. Gopalan vs. State of Madras

- Year of Judgement: 1950

- Popular Name: Preventive Detention case

- Related Topic/Issue: Procedure established by law

- Related Article: Articles 21 & 22

Supreme Court Judgement

It invalidated Section 14 of the impugned Preventive Detention Act (1950) on the ground that it violates the fundamental right guaranteed under Article 22. The Supreme Court declared the rest of the Act as valid and effective, emphasizing that the omission of this section does not change the nature, structure, or object of the legislation. Additionally, it ruled that the expression 'personal liberty' under Article 21 refers to the liberty of the physical body, i.e., freedom from physical restraint or detention. Moreover, it held that Article 21 provides protection only against executive actions, not legislative actions.

Impact of the Judgement

In this judgement, the Supreme Court adopted a narrow (restrictive) interpretation of Article 21, known as the 'textualist approach.' It held that the term 'law' in Article 21 refers to state-made law, not the principles of natural justice. Consequently, the expression 'procedure established by law' in Article 21 cannot be interpreted to mean the same as the American expression 'due process of law.' This declaration implies that the protection under Article 21 is available only against arbitrary executive actions, not arbitrary legislative actions. This interpretation prevailed for nearly three decades (1950 to 1978) until the Supreme Court, in the Maneka Gandhi case (1978), overruled this decision by adopting a wider interpretation of Article 21.

3. Champakam Dorairajan Case (1951)

- Name of the Case: State of Madras vs. Champakam Dorairajan

- Year of Judgement: 1951

- Popular Name: Communal reservation in admission to educational institutions

- Related Topic/Issue: Articles 15, 29, and 46

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court affirmed the judgement of the Madras High Court, striking down the Communal G.O. issued by the Madras Government. The G.O. provided for the proportionate reservation of seats in government medical and engineering colleges for different communities to promote the educational interests of backward classes under Article 46. The Supreme Court held that the Communal G.O. based on religion, race, and caste violated Articles 15(1) and 29(2). It emphasized that directive principles cannot override or curtail fundamental rights and must conform to and run as subsidiary to fundamental rights.

Impact of the Judgement

This judgement resulted in the addition of a new Clause (4) in Article 15 through the 1st Amendment Act (1951). This clause allows the state to make special provisions for the advancement of socially and educationally backward classes or for the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. Consequently, the effect of this judgement was nullified.

4. Shankari Prasad Case (1951)

- Name of the Case: Shankari Prasad vs. Union of India

- Year of Judgement: 1951

- Popular Name: Parliament's power to amend the constitution

- Related Topic/Issue: Articles 13 and 368

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court held that Parliament's amending power under Article 368 includes the authority to amend the fundamental rights guaranteed in Part III of the Constitution. It further clarified that a constitutional amendment act aimed at abridging or taking away fundamental rights is not void under Article 13(2). The court upheld the validity of the 1st Amendment Act (1951), which restricted the right to property by introducing Articles 31A and 31B.

Impact of the Judgement

In this judgement, the Supreme Court distinguished between legislative law (ordinary law) and constituent law (constitutional amendment law). It separated the ordinary legislative power of Parliament from its constituent power. The court asserted that the term 'law' in Article 13(2) pertains to an ordinary law and does not include a constituent law made under Article 368. Therefore, it established that Parliament can amend any provision of the constitution, rejecting the notion that Fundamental Rights are inviolable. This judgement remained authoritative for a decade and a half (1951 to 1967). Although reaffirmed in the Sajjan Singh case (1964), it was eventually overruled in the Golak Nath case (1967).

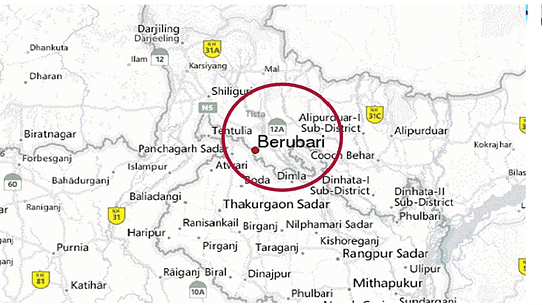

5. Berobari Union Case (1960)

Name of the Case: Berubari Union vs. Unknown

- Year of Judgement: 1960

- Popular Name: Cession of Indian Territory to a Foreign State

- Related Topic/Issue: Article 3, Article 368, and First Schedule

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court ruled that the power of Parliament under Article 3, allowing the reduction of a state's area, does not extend to the cession of Indian territory to a foreign country. It clarified that Article 3 deals with the internal adjustment among the territories of the constituent states of the Indian Union. Consequently, the cession of Indian territory to a foreign state requires a constitutional amendment under Article 368, enabling alterations to the First Schedule. The court also emphasized that the Preamble is not a part of the constitution.

Impact of the Judgement

This judgement prompted the enactment of the 9th Amendment Act (1960), facilitating the transfer of certain territory, known as Berubari Union in West Bengal, to Pakistan. The transfer was executed in accordance with the provisions of the Indo-Pak Agreement (Nehru-Noon Agreement) of 1958, specifically addressing Berubari Union and the Exchange of Cooch-Behar Enclaves.

6. K.M. Nanavati Case (1961)

- Name of the Case: K.M. Nanavati vs. State of Maharashtra

- Year of Judgement: 1961

- Popular Name: Jury System of Trial

- Related Topic/Issue: Impact of the Judgement

- Related Article/Schedule: N/A

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court affirmed the Bombay High Court's judgement, upholding the conviction of Nanavati under Section 302 of the Indian Penal Code and the life imprisonment sentence for the murder of his wife's paramour.

Impact of the Judgement

This judgement highlighted the deficiencies in the Jury System, eventually leading to its abolition. Despite this case, some jury trials persisted in the country. However, the enactment of the new Code of Criminal Procedure in 1973 completely eliminated the trial by jury system in India. Additionally, Nanavati, after spending three years in prison, was granted a pardon by the Governor.

7. I.C. Golak Nath Case (1967)

- Name of the Case: I.C. Golak Nath vs. State of Punjab

- Year of Judgement: 1967

- Popular Name: Parliament's power to amend the constitution

- Related Topic/Issue: Impact of the Judgement

- Related Article/Schedule: 13 & 368

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court, in this case, overturned its previous rulings in the Shankari Prasad case (1951) and the Sajjan Singh case (1964). It declared that the amending power under Article 368 cannot be utilized to diminish or eliminate the fundamental rights guaranteed in Part III of the constitution. The court clarified that a constitutional amendment act is considered a law under Article 13(2). However, it specified that the 1st Amendment Act (1951), the 4th Amendment Act (1955), and the 17th Amendment Act (1964) would remain valid for the future. The judgement was subject to the doctrine of prospective overruling, meaning it had only forward-looking application and not retroactive effect.

Impact of the Judgement

Following this judgement, the 24th Amendment Act (1971) was enacted. This amendment affirmed that Parliament possesses the authority to amend any part of the constitution, including fundamental rights, in line with the procedure outlined in Article 368. It also stipulated that a constitutional amendment act would not be regarded as a law according to Article 13(2). Consequently, this amendment aimed to override the aforementioned judgement.

8. Kesavananda Bharati Case (1973)

- Name of the Case: Kesavananda Bharati vs. State of Kerala

- Year of Judgement: 1973

- Popular Name: Fundamental Rights case

- Related Topic/Issue: Parliament's power to amend the constitution

- Related Article/Schedule: 13 & 368

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court, in this case, overturned its prior decision in the Golak Nath cases (1967). It established that Parliament, exercising its constituent power under Article 368, can amend any provision of the Constitution, including those related to fundamental rights, with the exception of the 'basic structure' of the constitution. The validity of the 24th Amendment Act (1971) and certain provisions of the 25th Amendment Act (1971) were upheld, while specific parts of the latter were declared invalid. The court also validated the 29th Amendment Act (1971).

Impact of the Judgement

This landmark judgement introduced the doctrine of the basic structure of the constitution, limiting Parliament's amending power. Subsequent cases applied this doctrine to assess the validity of constitutional amendments. The Supreme Court expanded the elements of the basic structure in various instances. In response to this judgement, the 42nd Amendment Act (1976) granted Parliament unrestricted authority to amend the constitution, which is further explained in the subsequent case.

9. Indira Nehru Gandhi Case

- Name of the Case: Indira Nehru Gandhi vs. Raj Narain

- Year of Judgement: 1975

- Popular Name: Election case

- Related Topic/Issue: Basic structure of the constitution, 329A (Repealed)

- Related Article/Schedule: -

Supreme Court Judgement

In this case, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the doctrine of the basic structure of the constitution. It invalidated clause (4) of Article 329A, introduced by the 39th Amendment Act (1975), which excluded election disputes involving the Prime Minister and the Speaker of Lok Sabha from the jurisdiction of all courts. The court held that this provision exceeded the amending power of Parliament as it affected the basic structure of the constitution.

Impact of the Judgement

Following the decisions in Kesavananda Bharati and Indira Nehru Gandhi cases, the 42nd Amendment Act (1976) added Clauses (4) and (5) to Article 368. Clause (4) stated that amendments made under Article 368, including those related to fundamental rights, cannot be challenged in any court. Clause (5) declared no limitations on Parliament's constituent power under Article 368. These clauses aimed to weaken the doctrine of the basic structure, which had been recognized as a restriction on Parliament's amending power.

10. A.D.M. Jabalpur Case (1976)

Name of the Case: A.D.M. Jabalpur vs. Shivakant Shukla

- Year of Judgement: 1976

- Popular Name: Habeas Corpus case

- Related Topic/Issue: Right to Life and Personal Liberty during the emergency

- Related Article/Schedule: 21 & 359

Supreme Court Judgement

The Supreme Court held that Article 21 is the exclusive repository of the right to life and personal liberty against the state. If the enforcement of that right is suspended by a Presidential Order under Article 359, then the detenu would have no standing to file a writ petition challenging the legality of the detention. Due to the Presidential Order dated 27th June 1975, no person had standing to move a petition before a High Court under Article 226 for a writ of habeas corpus or any other writ to contest the legality of a detention order on any ground. The court upheld the constitutional validity of Section 16A(9) of the Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA), 1971.

Impact of the Judgement

In this case, the Supreme Court adopted a restrictive interpretation of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21, delivering a flawed judgement. The court argued that any claim to a writ of habeas corpus amounted to the enforcement of the right to life and personal liberty suspended by the Presidential Order. This judgment failed to fulfill its role as the defender and guarantor of fundamental rights during the emergency (1975-77). Subsequently, the 44th Amendment Act (1978) amended Article 359, stating that the enforcement of the right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 cannot be suspended by a Presidential Order. In light of this amendment, the judgment in this case is no longer considered valid and holds only academic importance.

|

151 videos|780 docs|202 tests

|

FAQs on Laxmikant Summary: Landmark Judgements and Their Impact- 1 - Indian Polity for UPSC CSE

| 1. What is the Romesh Thappar Case (1950)? |  |

| 2. What was the impact of the A.K. Gopalan Case (1950)? |  |

| 3. What was the Champakam Dorairajan Case (1951) about? |  |

| 4. What did the Shankari Prasad Case (1951) establish? |  |

| 5. What was the significance of the Berubari Union Case (1960)? |  |