Laxmikant Summary: Important Doctrines of Constitutional Interpretation- 1 | Indian Polity for UPSC CSE PDF Download

Introduction

Understanding constitutional interpretation is essential for those navigating governance and jurisprudence. As aspirants pursue civil services, a grasp of key doctrines like the 'Golden Rule,' 'Literal Rule,' 'Mischief Rule,' 'Purposive Interpretation,' and 'Harmonious Construction' becomes crucial. Beyond exam preparation, mastering these doctrines equips individuals with the intellectual tools needed to unravel constitutional complexities and contribute meaningfully to public service, making it an indispensable skill set for a fulfilling career.

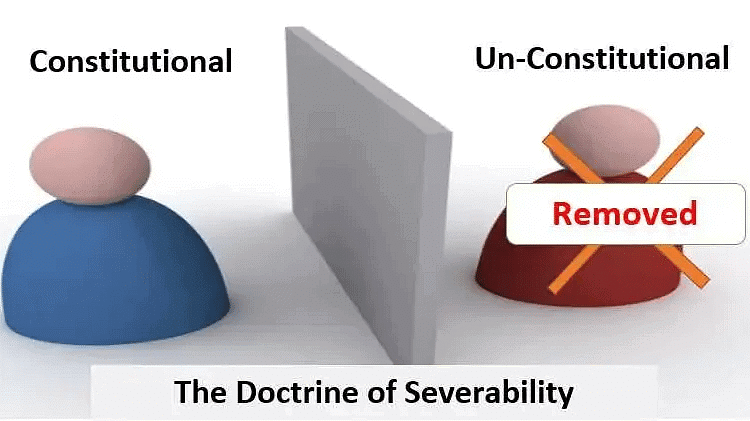

Doctrine of Severability

Meaning of the Doctrine

The doctrine of severability, also known as the doctrine of separability, was developed by the Supreme Court to address the issue of the validity of laws declared unconstitutional. When a part of a law is found unconstitutional, the question arises whether the entire law should be void or only the unconstitutional part. According to this doctrine, if the offending provision can be separated from the constitutional part, only the offending part is declared void, not the entire law. If separation is not possible, the whole law is declared void.

Basis of the Doctrine

Article 13 forms the basis of the doctrine of severability. Article 13(1) deals with pre-constitution laws, declaring them void to the extent of inconsistency with Fundamental Rights. Article 13(2) pertains to post-constitution laws, stating that any law contravening Fundamental Rights is void to the extent of the contravention.

Propositions of the Doctrine

- The intention of the legislature is the determining factor in deciding whether valid parts of a statute are separable from invalid parts. The test involves considering whether the legislature would have enacted the valid part knowing the rest was invalid.

- If valid and invalid provisions are so intertwined that separation is impossible, the invalidity of a portion renders the entire Act invalid. If they are distinct, the remaining valid portion may be upheld independently.

- If valid and invalid provisions form part of a single operative scheme, the invalidity of a part affects the entire scheme's failure.

- If what remains after omitting the invalid portion is substantially different, it may be rejected entirely.

- The separability does not depend on the law's form but on the substance, examining the Act as a whole and the setting of the relevant provision.

- If what remains after expunging the invalid portion requires alterations for enforcement, the whole must be struck down to avoid judicial legislation.

- The legislative intent considers the history, object, title, and preamble of the legislation.

Important Cases

- A.K. Gopalan vs. State of Madras (1950): Struck down a section but upheld the rest of the Preventive Detention Act.

- State of Bombay vs. F.N. Balsara (1951): Declared specific sections of the Bombay Prohibition Act as ultra vires but upheld the remaining provisions.

- R.M.D. Chamarbaugwalla vs. Union of India (1957): Held Prize Competitions Act provisions were severable, striking down those related to gambling competitions.

- Minerva Mills vs. Union of India (1980): Struck down specific sections of the 42nd Amendment Act but upheld the rest.

- Kihoto Hollohan vs. Zachillhu (1992): Declared a portion of the Tenth Schedule unconstitutional but upheld the rest.

Doctrine of Waiver

Meaning of the Doctrine

The doctrine of waiver is based on the concept that an individual entitled to a right or privilege has the freedom to voluntarily relinquish or give up that right or privilege. It involves a conscious abandonment of an existing legal right, benefit, claim, or privilege. Waiver is essentially an agreement not to assert a right, requiring full knowledge and intentional abandonment.

Position in India

In India, the doctrine of waiver is not applicable to fundamental rights. Citizens in India cannot waive their fundamental rights as they are considered mandatory for the state and essential to achieve the objectives outlined in the Preamble. The Supreme Court has emphasized that fundamental rights are not included in the constitution solely for individual benefit but as a matter of public policy. Therefore, the doctrine of waiver has no application to provisions of law established as constitutional policy.

Important Cases Relating to the Doctrine of Waiver

- Behram Khurshid Pesikaka vs. State of Bombay (1954): Held that in a criminal prosecution, an accused person cannot waive fundamental rights to get convicted.

- Basheshar Nath vs. Commissioner of Income Tax (1958): Rejected the argument that entering into an agreement to pay tax constitutes a waiver of fundamental rights.

- Olga Tellis vs. Bombay Municipal Corporation (1985): Affirmed that a person cannot waive fundamental rights, and there can be no estoppel against the constitution.

- Nar Singh Pal vs. Union of India (2000): Reiterated that fundamental rights under the constitution cannot be bartered away, compromised, or subjected to estoppel.

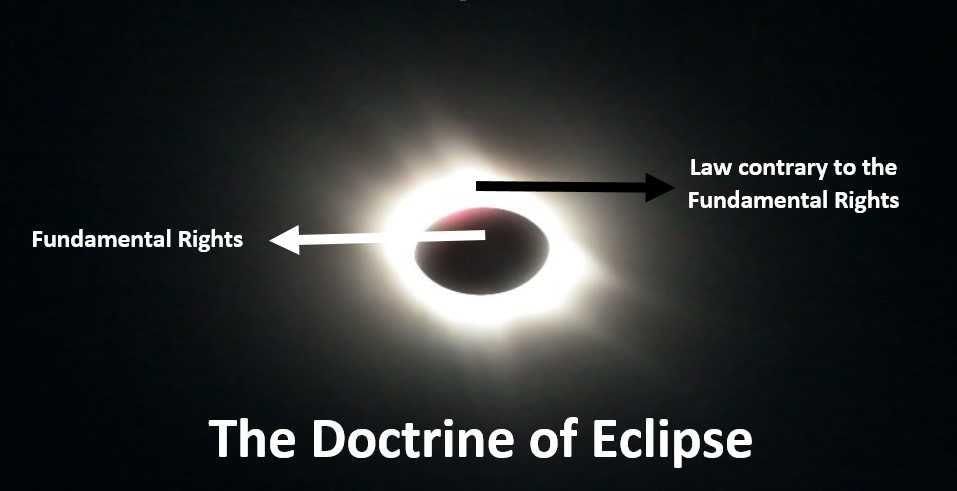

Doctrine of Eclipse

Meaning of the Doctrine

The doctrine of eclipse arises from the prospective nature of Article 13(1) of the constitution, declaring pre-constitution laws void to the extent of inconsistency with Fundamental Rights. It posits that such laws, inconsistent with a fundamental right, are not nullities but become inoperative from the constitution's commencement, remaining dormant yet not entirely erased from the statute book. The doctrine applies (i) to past transactions, (ii) for rights acquired and liabilities incurred pre-constitution, and (iii) to non-citizens without fundamental rights.

Formulation of the Doctrine

The Bhikaji case (1955) introduced the doctrine. It held that a pre-constitutional law inconsistent with a fundamental right is eclipsed, rendered inoperative but not void, until the relevant fundamental right is amended, making the law enforceable again. The doctrine was not applicable to post-constitutional laws, but subsequent cases like Ambica Mills (1974) and Dulare Lodh (1984) introduced exceptions, allowing its application to post-constitutional laws against citizens under certain circumstances.

Doctrine of Territorial Nexus

Meaning of the Doctrine

The doctrine of territorial nexus is linked to Article 245, governing the legislative extent of Parliament and State Legislatures. While Parliament can make laws for the entire territory of India, including "extra-territorial legislation," State Legislatures lack this authority. However, an exception exists for extra-territorial legislation by a State Legislature if there is a sufficient nexus between the state and the subject matter, known as the doctrine of territorial nexus.

Formulation of the Doctrine

In pre-Constitution cases like Raleigh (1944), Wallace (1948), and Wulla (1949), the doctrine was applied to income-tax laws. In the post-Constitution era, the Supreme Court, in cases like R.M.D. Chamarbaugwalla (1957), TISCO (1958), and NTPC (2002), emphasized the need for a real and non-illusory nexus for a law to have extra-territorial operation. It is not limited to tax laws but extends to other legislation.

Application to Non-Tax Laws

The doctrine applies not only to tax laws but also to other legislations. In cases like Charusila Dasi (1959) and Shrikant (1994), the Supreme Court upheld the validity of state laws concerning trusts and agricultural land ceilings, respectively, even when part of the subject matter was outside the state.

Exceptions to the Doctrine

The doctrine of territorial nexus has exceptions, such as when a state government approves inter-state routes under the Motor Vehicles Act (Khazan Singh, 1973) or when a state engages in trade and business under Article 298, not limited to its boundaries (Khazan Singh, 1973).

Doctrine of Pith and Substance

Meaning of the Doctrine

Article 246 outlines the distribution of legislative powers between Parliament and State Legislatures through three lists. The doctrine of pith and substance comes into play when there is an alleged encroachment, determining the validity of the law. It mandates that the law should be analyzed as an organic whole, considering its main objectives and the scope and effect of its provisions.

Rationale of the Doctrine

The doctrine of pith and substance originated from the Privy Council's decisions on legislative competence in federations like Canada and Australia. In a federal constitution, a distribution of legislative powers between the Centre and the States necessitates resolving overlapping issues to avoid stifling beneficent legislation. The essence lies in understanding the true nature and character of the law in question.

Principles of the Doctrine

In the pre-Constitution era, the Privy Council, in the Prafulla Kumar case (1947), established key principles of the doctrine of pith and substance. It emphasized looking at the overall effect of the enactment and determining its true nature and character in relation to legislative lists. The priorities among Lists I, II, and III were outlined, with List I having precedence. The doctrine focuses on the substance of the Act and its true character rather than the degree of invasion into other lists.

Supreme Court Judgements

- State of Bombay vs. F.N. Balsara (1951): Upheld the validity of the Bombay Prohibition Act, 1950.

- D.N. Banerji vs. P.R. Mukherjee (1952): Upheld the validity of the Industrial Disputes Act of the Parliament.

- State of Rajasthan vs. G. Chawla (1958): Upheld the validity of the Rajasthan Act restricting the use of sound amplifiers.

- State of Gujarat vs. Shantilal Mangaldas (1969): Affirmed that pith and substance determine legislative competence and are irrelevant to fundamental rights infringement.

- M. Ismail Faruqui vs. Union of India (1994): Upheld the validity of the Acquisition of Certain Area at Ayodhya Act, 1993, stating it fell within the ambit of the Concurrent List.

- Sameer Ahmed Iatifiur Rehman Sheikh vs. State of Maharashtra (2010): Upheld the validity of the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act, 1999.

Doctrine of Colourable Legislation

Meaning of the Doctrine

Article 246 of the constitution outlines the division of legislative powers between Parliament and State Legislatures, defining subjects in Union, State, and Concurrent Lists. The doctrine of colourable legislation comes into play when a legislature enacts a law that, though appearing within its competence, goes beyond its ambit in substance and effect. This results in the law being declared void, emphasizing that the pretense or disguise given to the law doesn't save it from invalidity. Colourable legislation arises when a legislature lacks the power to legislate on a subject, either due to exclusion from its assigned list or constitutional limitations.

Propositions of the Doctrine

- If the constitution distributes legislative powers, questions arise about whether a legislature, in a particular case, has transgressed its limits. Colourable legislation refers to disguised transgressions that veiledly go beyond constitutional powers.

- The essence lies in the substance of the Act, not just its form. If the subject-matter, in substance, exceeds legislative powers, the form or appearance doesn't save it from condemnation.

- The legislature cannot use an indirect method to violate constitutional prohibitions. The true nature and character of the legislation, considering its effect, purpose, and design, determine its constitutionality.

- The doctrine doesn't concern the motives (bona fides or mala fides) but focuses on the competency of the legislature. Constitutional compliance is the key factor in determining whether a statute is valid.

- When scrutinizing a statute alleged to be a colourable device, the court examines the entire legislation and related acts to ascertain its true nature and character, ensuring it doesn't form part of a scheme to achieve an invalid objective.

Doctrine of Fraud on the Constitution

The doctrine of colourable legislation is synonymous with the doctrine of fraud on the constitution. In this context, the court observes that colourable legislation is legislation ostensibly under constitutional powers but, in reality, falls outside that power. The charge of 'fraud on the Constitution' is a way of expressing non-compliance with constitutional terms, where the legislature pretends to act within its power while not doing so.

Doctrine of Fraud on Legislative Power

It's crucial to differentiate the doctrine of fraud on the Constitution from fraud on legislative power. The former involves a constitutional prohibition, making an enactment a fraud when the legislature lacks power. The latter means the legislature has the power but doesn't exercise it as required, resulting in a mere pretence of law that courts won't acknowledge.

Supreme Court Judgements

- State of Bihar vs. Kameshwar Singh (1952): Invalidated the Bihar Land Reforms Act, 1950, deeming the compensation provision a pretension.

- K.C. Gajapati Narayan Deo vs. State of Orissa (1953): Upheld the validity of the Orissa Agricultural Income tax (Amendment) Act, 1950, stating it fell within the legislative competency of the State legislature.

- K.T. Moopil Nair vs. State of Kerala (1960): Declared the Travancore-Cochin Land Tax Act, 1955, invalid, citing violations of Articles 14 and 19(1)(f).

- M.R. Balaji vs. State of Mysore (1962): Declared the State order reserving 68% of seats in educational institutions void, stating it was a fraud on the Constitution violating Article 15(4).

Doctrine of Implied Powers

Meaning of the Doctrine

The doctrine of implied powers, also known as the doctrine of implication, is grounded in the maxim that "whoever grants a thing is deemed also to grant that without which the grant itself would be of no effect." Implied powers refer to political powers not explicitly enumerated but necessary for carrying out express powers.

According to Black's Law Dictionary, "implied power" signifies "a political power that is not enumerated but that nonetheless exists because it is needed to carry out an express power."

In explaining the doctrine, legal scholars emphasize that when a legislature enables something to be done, it implies the power to do everything indispensable for the intended purposes.

Scope of the Doctrine

The Supreme Court clarifies that the doctrine of implied powers is legitimately invoked when a duty is imposed or a power conferred by statute, and it's found impossible to discharge that duty or exercise that power without assuming some auxiliary or incidental power. This doctrine prevents a statutory provision from becoming impossible to comply with, ensuring enforceability.

Application of the Doctrine

The Supreme Court has applied the doctrine of implied powers in various constitutional cases:

- In the Gopal Chandra Misra case (1978), the Supreme Court affirmed that a judge of a State High Court has the implied power under Article 217 to revoke resignation even after receipt of the resignation letter.

- In the Rupa Ashok Hurra case (2002), the Supreme Court recognized its inherent power to reconsider its own judgments, allowing the filing of a curative petition for preventing abuse of its process and correcting gross miscarriages of justice.

- In the Raja Ram Pal case (2007), the Supreme Court held that Parliament has the implied power under Article 105 to expel its members for contempt.

- In the Salil Sabhlok case (2013), the Supreme Court established that Article 316, granting the State Governor the power to appoint members of the State Public Service Commission, implies the power to lay down procedures for such appointments.

Doctrine of Implied Prohibition

Conversely, the doctrine of implied prohibition, based on the maxim "express mention of one thing implies the exclusion of another," is applicable in the USA and Australia but not in India. In India, both the Central and State Legislatures have enumerated powers, and the doctrine of incidental and ancillary powers is recognized.

|

147 videos|780 docs|202 tests

|

FAQs on Laxmikant Summary: Important Doctrines of Constitutional Interpretation- 1 - Indian Polity for UPSC CSE

| 1. What is the doctrine of severability? |  |

| 2. What is the doctrine of waiver? |  |

| 3. What is the doctrine of eclipse? |  |

| 4. What is the doctrine of territorial nexus? |  |

| 5. What is the doctrine of pith and substance? |  |