Laxmikanth Summary: Centre - State Relations | Indian Polity for UPSC CSE PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Introduction |

|

| Legislative Relations |

|

| Administrative Relations |

|

| Financial Relations |

|

| Trends in Centre-State Relations |

|

Introduction

The Constitution of India, being federal in structure, divides all powers (legislative, executive and financial) between the Centre and the states. The Centre-State relations can be studied under three heads:

- Legislative relations.

- Administrative relations.

- Financial relations

Legislative Relations

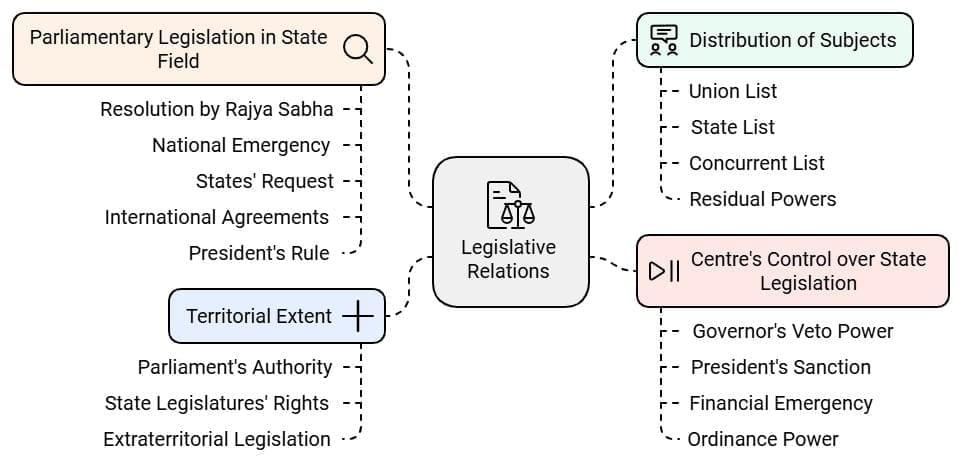

Articles 245 to 255 in Part XI of the Constitution specifically address legislative relations between the Centre and the states, supplemented by additional articles on the same theme. Thus, there are four aspects in the Centre-states legislative relations, viz.,

1. Territorial extent of Central and state legislation

The Constitution defines the territorial limits of the legislative powers vested in the Centre and the states in the following way:

(i) The Parliament can make laws for the whole or any part of the territory of India.

(ii) A state legislature can make laws for the whole or any part of the state.

(iii) The Parliament alone can make ‘extra-territorial legislation'.

Nevertheless, the Constitution imposes certain limitations on the comprehensive territorial jurisdiction of Parliament. Specifically:

- The President can establish regulations for maintaining peace, progress, and good governance in Union Territories such as the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Dadra and Nagar Haveli, Daman and Diu, and Ladakh. In the case of Puducherry, the President can enact regulations only during the suspension or dissolution of the Assembly. These regulations carry the same legal weight as an act of Parliament and can modify or annul any parliamentary act related to these Union Territories.

- Governors have the authority to instruct that a parliamentary act does not apply to a scheduled area in the state or to apply with specific modifications and exceptions.

- The Governor of Assam can similarly direct that a parliamentary act does not apply to a tribal area (autonomous district) in the state or apply with specified modifications and exceptions. The President holds the same power regarding tribal areas (autonomous districts) in Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

2. Distribution of Legislative Subjects

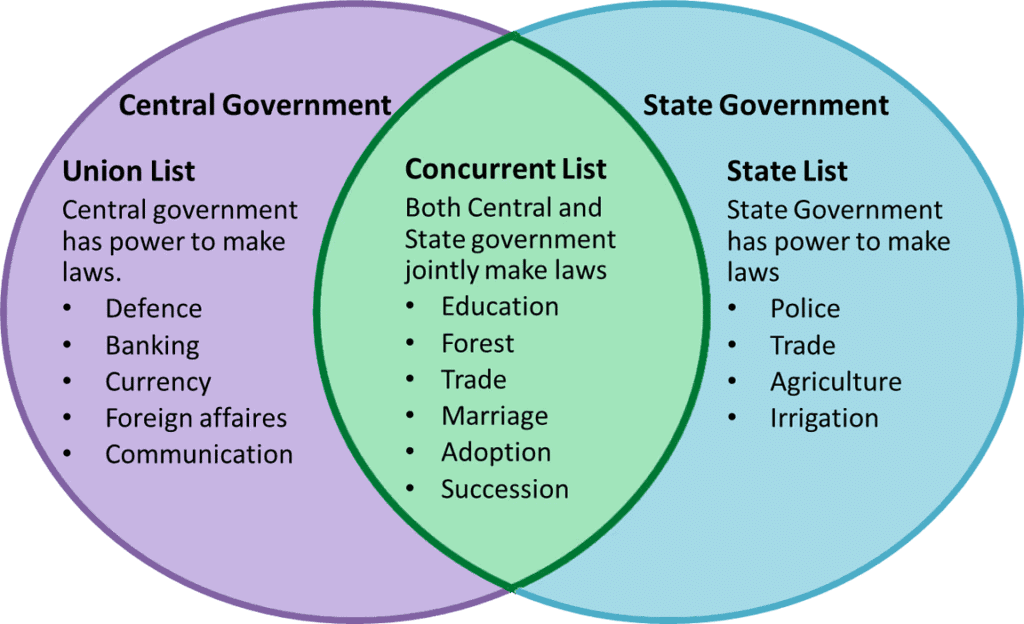

The Constitution establishes a three-fold distribution of legislative subjects among the Centre and the states, outlined in List-I (the Union List), List-II (the State List), and List-III (the Concurrent List) in the Seventh Schedule:

The Parliament has exclusive powers to make laws with respect to any of the matters enumerated in the Union List. This list has at present 100 subjects (originally 97 subjects) like defence, banking, foreign affairs, currency, atomic energy, insurance, communication, inter-state trade and commerce, census, audit and so on.

The state legislature has “in normal circumstances” exclusive powers to make laws with respect to any of the matters enumerated in the State List. This has at present 61 subjects (originally 66 subjects) like public order, police, public health and sanitation, agriculture, prisons, local government, fisheries, markets, theatres, gambling and so on.

Both the Parliament and state legislatures can enact laws on subjects mentioned in the Concurrent List, covering 52 subjects(originally 47 subjects), including criminal law, civil procedure, marriage and divorce, population control, family planning, electricity, labour welfare, economic and social planning, drugs, newspapers, books, and printing presses.

Parliament retains the authority to legislate on any matter for any part of India not included in a state, even if that matter is listed in the State List, particularly referring to Union Territories or Acquired Territories.

The 101st Amendment Act of 2016 introduced a special provision for goods and services tax, granting powers to both Parliament and state legislatures. Parliament has exclusive authority over goods and services tax in the case of inter-state trade or commerce.

The power to legislate on residual subjects, i.e., matters not enumerated in the three lists, rests with Parliament, including the authority to levy residual taxes.

3. Parliamentary Legislation in the State Field

The outlined system for the distribution of legislative powers between the Centre and the states is designed for normal circumstances. However, in extraordinary situations, this distribution can be altered or temporarily suspended as granted by the Constitution. The Parliament is empowered to legislate on matters enumerated in the State List under the following five exceptional circumstances:

- Resolution by Rajya Sabha: If the Rajya Sabha, with the support of two-thirds of its members present and voting, deems it necessary in the national interest for Parliament to legislate on goods and services tax or a State List matter, the Parliament gains the authority to do so. This resolution is valid for one year and can be renewed multiple times, but not exceeding one year each time. The laws cease to be effective six months after the resolution expires. State legislatures retain the power to legislate on the same matter, but in case of inconsistency between state and parliamentary laws, the latter prevails.

- National Emergency: During a national emergency, Parliament can legislate on goods and services tax or State List matters. The laws become ineffective six months after the emergency concludes. State legislatures maintain their authority to legislate on the same matters, but parliamentary laws take precedence in case of conflict.

- States' Request: If the legislatures of two or more states pass resolutions urging Parliament to enact laws on a State List matter, Parliament can legislate on that subject. The law applies only to the states that requested it, but any other state can adopt it later by passing a resolution. Amendments or repeals can only be done by Parliament, not the concerned state legislatures.

- Implementing International Agreements: Parliament can legislate on State List matters to implement international treaties, agreements, or conventions, allowing the Central government to fulfil its international obligations. Examples include laws related to the United Nations (Privileges and Immunities) Act, 1947, Geneva Convention Act, 1960, Anti-Hijacking Act, 1982, and environmental and TRIPS legislation.

- President's Rule: During the imposition of the President's rule in a state, Parliament gains the authority to legislate on State List matters related to that state. Laws enacted during the President's rule remain in force even after its conclusion. However, state legislatures have the power to repeal, alter, or re-enact such laws.

4. Centre's Control over State Legislation

The Constitution empowers the Centre to exercise control over the state's legislative matters in the following ways:

I. The governor can reserve certain types of bills passed by the state legislature for the consideration of the President. The president enjoys absolute veto over them.

II. Bills on certain matters enumerated in the State List can be introduced in the state legislature only with the previous sanction of the president.

III. The President can direct the states to reserve money bills and other financial bills passed by the state legislature for his consideration during a financial emergency.

Administrative Relations

Articles 256 to 263 in Part XI of the Constitution specifically address administrative relations between the Centre and the states. Additionally, various other articles within the Constitution pertain to the same subject.

1. Distribution of Executive Powers

The executive power is distributed between the Centre and the states in alignment with the division of legislative powers, with few exceptions. The executive authority of the Centre covers the entire territory of India:

- to the matters on which the Parliament has exclusive power of legislation (i.e., the subjects enumerated in the Union List); and

- to the exercise of rights, authority and jurisdiction conferred on it by any treaty or agreement.

2. Obligation of States and the Centre

The Constitution has placed two restrictions on the executive power of states to allow ample scope for the Centre to exercise its executive authority without hindrance. These restrictions dictate that the executive power of each state must be utilized:

- as to ensure compliance with the laws made by the Parliament and any existing law which apply in the state; and

- as not to impede or prejudice the exercise of executive power of the Centre in the state.

3. Centre's Directions to the States

In addition to the previously mentioned cases, the Centre has the authority to issue directions to the states concerning the exercise of their executive power in the following matters:

- The construction and maintenance of means of communication declared to be of national or military importance, by the state.

- Measures to be taken for the protection of railways within the state.

- The provision of adequate facilities for instruction in the mother tongue at the primary stage of education to children belonging to linguistic minority groups in the state.

- The formulation and execution of specified schemes for the welfare of the Scheduled Tribes in the state.

Similar to the coercive sanction applicable to Central directions under Article 365 (mentioned above), the same sanction is also relevant in these cases.

4. Mutual Delegations of Functions

The allocation of legislative powers between the Centre and the states is rigid:

- No delegation to states: The Constitution strictly prohibits the Centre from delegating its legislative authority to the states.

- No state request to Parliament: Similarly, a single state is not allowed to request Parliament to enact a law on a subject within its jurisdiction.

The distribution of executive power generally mirrors the distribution of legislative powers:

- Potential for conflicts: The strict division in the executive realm may lead to occasional conflicts between the Centre and the states.

To address potential conflicts, the Constitution allows for the inter-government delegation of executive functions:

- Mutual delegation: The President, with the consent of the state government, can entrust any of the executive functions of the Centre to that government.

- Reciprocal delegation: Conversely, the governor of a state, with the consent of the Central government, may entrust any of the executive functions of the state to the Centre. This mutual delegation of administrative functions can be either conditional or unconditional.

The Constitution also allows for the entrustment of the executive functions of the Centre to a state without the consent of that state:

- Delegation by Parliament: In this case, the delegation is done by Parliament, not the President.

- Unilateral authority: A law enacted by Parliament on a subject in the Union List can confer powers and impose duties on a state or authorize the Centre to confer powers and impose duties on a state, regardless of the state's consent.

- Limitations on state legislature: It's important to note that a state legislature does not have the authority to do the same.

In summary, mutual delegation of functions between the Centre and the state can occur either through an agreement or by legislation:

- Centre's flexibility: The Centre can employ both methods.

- State's limitation: A state is limited to using the agreement method.

5. Cooperation between Centre and States

The Constitution includes provisions to ensure cooperation and coordination between the Centre and the states:

- The Parliament has the authority to establish mechanisms for the resolution of disputes or complaints related to the use, distribution, and control of waters from inter-state rivers and river valleys.

- The President can create an Inter-State Council under Article 263, tasked with investigating and discussing subjects of common interest between the Centre and the states. This council was established in 1990.

- Full faith and credit must be given throughout the territory of India to public acts, records, and judicial proceedings of both the Centre and every state.

- The Parliament has the power to appoint a suitable authority to implement the constitutional provisions concerning interstate freedom of trade, commerce, and intercourse. However, as of now, no such authority has been appointed.

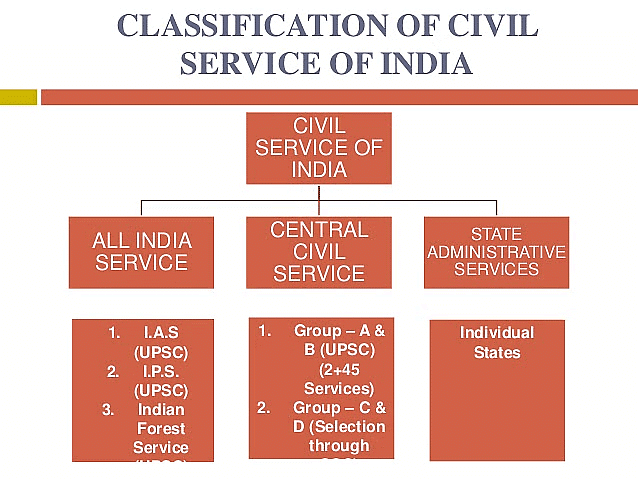

6. All India Services

- Like in any other federation, the Centre and the states also have their separate public services called as the Central Services and the State Services respectively. In addition, there are all-India services IAS, IPS and IFS. The members of these services occupy top positions (or key posts) under both the Centre and the states and serve them by turns. But, they are recruited and trained by the Centre.

7. Public Service Commissions

In the realm of public service commissions, the dynamics between the Centre and states are outlined as follows:

- The Chairman and members of a state public service commission, while appointed by the governor of the state, can only be removed by the President.

- The Parliament has the authority to establish a Joint State Public Service Commission (JSPSC) catering to two or more states, contingent upon the request of the concerned state legislatures. The Chairman and members of the JSPSC are appointed by the President.

- The Union Public Service Commission (UPSC) can address the requirements of a state with the governor's request and the President's approval.

- The UPSC assists states, especially when requested by two or more states, in formulating and implementing joint recruitment schemes for services that demand candidates with specific qualifications.

8. Integrated Judicial System

India's governance follows a dual polity structure, but it does not entail a dual system of justice administration.

The Constitution has implemented an integrated judicial system, wherein the Supreme Court holds the highest authority, and state high courts operate beneath it.

This unified judicial framework is responsible for enforcing both Central laws and state laws, aiming to eradicate variations in remedial procedures.

Judges for state high courts are appointed by the President, following consultations with the Chief Justice of India and the respective state's governor. The President also holds the power to transfer and remove these judges.

Parliament holds the authority to establish a common high court that serves multiple states. Examples include shared high courts for Maharashtra and Goa or Punjab and Haryana.

9. Relations During Emergencies

- In the event of a national emergency declared under Article 352, the Centre gains the authority to issue executive directives to a state on "any" matter. This brings state governments under the complete control of the Centre, although they are not suspended.

- When the President's Rule is imposed in a state, as per Article 356, the President can take on the functions of the state government and wield powers vested in the Governor or any other executive authority in the state.

- In the course of a financial emergency declared under Article 360, the Centre has the power to instruct states to adhere to financial propriety canons. Additionally, it can issue other necessary directives, including the reduction of salaries for individuals serving in the state.

10. Other Provisions

- Article 355 imposes two responsibilities on the Centre: (a) to safeguard every state against external aggression and internal disturbance; and (b) to ensure that the government of every state aligns with the provisions of the Constitution.

- The governor of a state, appointed by the President, serves at the pleasure of the President. Besides being the Constitutional head of the state, the governor also functions as an agent of the Centre within the state, submitting regular reports to the Centre on administrative affairs.

- The state election commissioner, appointed by the governor of the state, can only be removed by the President.

11. Extra - Constitutional Devices

- Constitutional Mechanisms: The Constitution incorporates various provisions to ensure cooperation and coordination between the Centre and the states.

- Extra-constitutional Mechanisms: In addition to constitutional provisions, there are non-constitutional devices aimed at fostering collaboration. These include advisory bodies and Central-level conferences.

- Non-constitutional Advisory Bodies: Examples of non-constitutional advisory bodies include the NITI Aayog, National Integration Council, Central Council of Health and Family Welfare, Zonal Councils, North-Eastern Council, Central Council of Indian Medicine, Central Council of Homoeopathy, Transport Development Council, and University Grants Commission.

- Important Conferences: Annual or periodic conferences play a crucial role in facilitating consultations between the Centre and states. These conferences include the governors' conference (presided over by the President), chief ministers' conference (presided over by the prime minister), chief secretaries' conference (presided over by the cabinet secretary), conference of inspector-general of police, chief justices' conference (presided over by the chief justice of India), conference of vice-chancellors, home ministers' conference (presided over by the Central home minister), and law ministers' conference (presided over by the Central law minister).

Financial Relations

1. Allocation of Taxing Powers

- The Constitution divides the taxing powers between the Centre and the states in the following way:

- The Parliament has exclusive power to levy taxes on subjects enumerated in the Union List, state, concurrent.

Additionally, the Constitution places specific constraints on state taxing powers:

- Limits are imposed on taxes related to professions, trades, callings, and employment, ensuring a balance in taxation.

- Restrictions are in place for taxing the supply of goods or services outside the state or in the course of import or export.

- The 101st Amendment Act of 2016 introduces concurrent power for Parliament and state legislatures to make laws governing goods and services tax.

- The Constitution also addresses taxation on the consumption or sale of electricity, and water, and the involvement of regulatory authorities established by Parliament for inter-state rivers or river valleys.

- State laws imposing such taxes require presidential consideration and assent for effectiveness, illustrating a careful delineation of powers between the Centre and states.

2. Distribution of Tax Revenues

The 80th Amendment of 2000 and the 88th Amendment of 2003 have introduced major changes in the scheme of the distribution of tax revenues between the centre and the states.

After these two Amendments, the present position in this regard is as follows:

A. Taxes Levied by the Centre but Collected and Appropriated by the States (Article 268): Article 268 specifies the duties imposed by the Union government but collected and claimed by the states, such as stamp duties and excise on medicinal and toilet treatments, despite the fact that they are listed in the Union List.

B. Service Tax Levied by the Centre but Collected and Appropriated by the Centre and the States (Article 268-A): Article 268-A deals with the service tax levied by the Centre but collected and appropriated by both the Centre and the States. This means that revenue generated from service tax is shared between the Centre and the States.

C. Taxes Levied and Collected by the Centre but Assigned to the States (Article 269): Article 269 pertains to taxes levied and collected by the Centre but assigned to the States. These taxes are assigned to the States as per the recommendations of the Finance Commission to ensure financial stability and autonomy at the state level.

D. Taxes Levied and Collected by the Centre but Distributed between the Centre and the States (Article 270): Article 270 addresses taxes levied and collected by the Centre, which are then distributed between the Centre and the States. This distribution is based on a specific formula outlined in the Constitution to allocate these tax revenues.

E. Surcharge on Certain Taxes and Duties for Purposes of the Centre (Article 271): The Parliament can at any time levy surcharges on certain taxes and duties for the purposes of the Centre. This allows the Centre to impose additional charges on specific taxes to meet particular financial requirements.

F. Taxes Levied and Collected and Retained by the States: This refers to taxes that are both levied and collected by the States, and the revenue generated from these taxes is retained by the respective States. These taxes contribute to the revenue of the State governments and are not shared with the Centre.

3. Distribution of Non-tax Revenues

- The Centre:The major sources of non-tax revenues for the Centre are derived from the following: (i) posts and telegraphs, (ii) railways, (iii) banking, (iv) broadcasting, (v) coinage and currency, (vi) central public sector enterprises, (vii) escheat and lapse, and (viii) other miscellaneous sources.

- The States:The receipts from the following form the major sources of non-tax revenues of the states: (i) irrigation; (ii) forests; (iii) fisheries; (iv) state public sector enterprises; (v) escheat and lapse; and (vi) others.

4. Grants-in-Aid to the States

- Statutory Grants:

Article 275 authorizes Parliament to allocate grants to states that require financial assistance, not necessarily every state. Different amounts may be specified for various states, and these sums are withdrawn from the Consolidated Fund of India annually.Beyond this general provision, the Constitution also outlines specific grants aimed at enhancing the well-being of scheduled tribes in a state or improving the administration in scheduled areas, such as in the State of Assam.

The grants stipulated in Article 275, both general and specific, are allocated to states based on the recommendations of the Finance Commission.

- Discretionary Grants:

Article 282 empowers both the Centre and the states to make any grants for any public purpose, even if it is not within their respective legislative competence. Under this provision, the Centre makes grants to the states. These grants, also known as discretionary grants, are named as such because the Centre is under no obligation to give these grants, and the matter lies within its discretion. The purpose of these grants is twofold: to help the state financially to fulfil plan targets, and to give some leverage to the Centre to influence and coordinate state action to effectuate the national plan. - Other Grants:

The Constitution also introduced a third category of grants-in-aid, albeit for a limited duration. It included provisions for grants in lieu of export duties on jute and jute products specifically for the states of Assam, Bihar, Orissa, and West Bengal. These grants were intended to be provided for ten years from the beginning of the Constitution. The funds were drawn from the Consolidated Fund of India and allocated to the states based on the recommendations of the Finance Commission.

5. Goods and Services Tax Council

Ensuring the effective administration of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) requires collaboration and coordination between the Centre and the States. To streamline this consultation process, the 101st Amendment Act of 2016 introduced the establishment of either the Goods and Services Tax Council or the CST Council.

Article 279-A grants the President the authority to form the GST Council via an order, serving as a collaborative platform for both the Centre and the States. . It is required to make recommendations to the Centre and the States on the following matters:

- The taxes, cesses, and surcharges imposed by the Centre, States, and local bodies that would be integrated into GST.

- Determining the goods and services that could be either included or excluded from GST.

- Establishing model GST laws and principles for the imposition of taxes, as well as the distribution of GST on supplies during inter-state trade or commerce, and the guiding principles for determining the place of supply.

- Setting the threshold turnover limit below which goods and services might be exempted from GST.

6. Finance Commission

Article 280 establishes the Finance Commission as a quasi-judicial entity, constituted by the President every fifth year or potentially earlier. Its primary responsibility is to provide recommendations to the President on several crucial matters:

The distribution of the net proceeds of taxes is to be shared between the Centre and the states, along with the allocation among states and their respective shares of such proceeds.

The principles governing grants-in-aid to states by the Centre are derived from the Consolidated Fund of India.

Measures are required to enhance the Consolidated Fund of a state to supplement the resources of panchayats and municipalities in the state, based on the recommendations of the State Finance Commission.

Any other matters referred to it by the President in the interest of sound finance.

Historically, until 1960, the Commission also recommended the amounts paid to the States of Assam, Bihar, Orissa, and West Bengal as compensation for not assigning any share of the net proceeds each year from the export duty on jute and jute products.

The Constitution envisions the Finance Commission as a crucial element in maintaining fiscal federalism in India.

7. Protection of States' Interest

To safeguard the interests of states in financial matters, the Constitution stipulates that certain bills can only be introduced in Parliament based on the President's recommendation. These bills include:

- A bill that imposes or modifies any tax or duty affecting states.

- A bill that alters the definition of 'agricultural income' as applicable to Indian income tax legislation.

- A bill impacting the principles governing the distribution of money to states.

- A bill imposing any surcharge on a specified tax or duty for the central government.

8. Borrowing by the Centre and the States

The Constitution outlines provisions concerning the borrowing powers of both the Central government and the states as follows:

The Central government has the authority to borrow within India or externally, utilizing the security of the Consolidated Fund of India, or providing guarantees. However, these actions must adhere to the limits set by Parliament. Currently, there is no legislation enacted by Parliament governing this.

Similarly, a state government can borrow within India, using the security of the Consolidated Fund of the State or offering guarantees. These actions are subject to limits specified by the legislature of that state.

The Central government is empowered to lend money to any state or guarantee loans raised by any state. Funds required for such loans are to be drawn from the Consolidated Fund of India.

A state is restricted from raising any loan without the consent of the Centre if any part of a loan from the Centre remains outstanding or if a guarantee has been extended by the Centre.

9. Inter-Governmental Tax Immunities

Like any other federal Constitution, the Indian Constitution also contains the rule of 'immunity from mutual taxation'and makes the following provisions in this regard:

- Exemption of Central Property from State Taxation:

The assets of the Central government are exempted from all taxes imposed by a state or any authority within a state, including municipalities, district boards, and panchayats. However, the Parliament has the authority to lift this exemption. The term 'property' encompasses lands, buildings, chattels, shares, debts, and anything with a monetary value, irrespective of whether it is movable or immovable, tangible or intangible. Additionally, the property may be utilized for sovereign purposes, such as the armed forces, or for commercial purposes.

Corporations or companies established by the Central government do not enjoy immunity from state or local taxation. This is because a corporation or company is considered a distinct legal entity. Exemption of State Property or Income from Central Taxation:

The property and income of a state are immune from Central taxation, whether derived from sovereign or commercial functions. However, the Centre can tax the commercial activities of a state if specified by Parliament. Parliament holds the authority to designate certain trades or businesses as incidental to the ordinary functions of the government, exempting them from taxation.

10. Effects of Emergencies

The Centre-state financial relations in normal times (described above) undergo changes during emergencies. These are as follows:

- National Emergency: During the declaration of a national emergency under Article 352, the President has the authority to alter the constitutional allocation of revenues between the Centre and the states. This implies that the President can diminish or annul the transfer of finances, encompassing both tax sharing and grants-in-aid, from the Centre to the states. This modification remains effective until the conclusion of the financial year in which the emergency ceases to be in operation.

- Financial Emergency: During the existence of a financial emergency under Article 360, the Centre can issue directives to the states. These directives include instructions:

- To adhere to specified principles of financial propriety.

- To decrease the salaries and allowances of all classes of individuals serving in the state.

- To reserve all money bills and other financial bills for the consideration of the President.

Trends in Centre-State Relations

Until 1967, the relations between the Centre and states were generally smooth, primarily because of the one-party rule at both the Centre and in most states. However, the political landscape underwent a significant shift in the 1967 elections. The Congress party, which had a stronghold, was defeated in nine states, weakening its position at the Centre. This marked a turning point in Centre-state relations.

The non-Congress governments in the states, emerging after the elections, opposed the growing centralization and intervention by the Central government. They emphasized the issue of state autonomy, demanding increased powers and financial resources for the states. This shift in dynamics led to tensions and conflicts in Centre-state relations.

Tension Areas in Centre-State Relations

The sources of tension and conflicts between the Centre and states include:

- Mode of appointment and dismissal of governors.

- Discriminatory and partisan role of governors.

- Imposition of President's Rule for partisan interests.

- Deployment of Central forces in states to maintain law and order.

- Reservation of state bills for the consideration of the President.

- Discrimination in financial allocations to the states.

- Role of the Planning Commission in approving state projects (until its replacement by the NITI Aayog in 2015).

- Management of All-India Services (IAS, IPS, and IFoS).

- Use of electronic media for political purposes.

- Appointment of enquiry commissions against the chief ministers.

- Sharing of finances between Centre and states.

- Encroachment by the Centre on the State List.

- Implementation of centrally sponsored schemes by the states.

- Modus operandi of central agencies like CBI, ED, and so on.

These issues in Centre-State relations have been under consideration since the mid-1960s.

In this direction, the following developments have taken place:

Administrative Reforms Commission

The Central government established the First Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) of India in 1966, comprising six members and chaired initially by Morarji Desai, later succeeded by K Hanumanthayya. The commission's terms of reference included the examination of Centre-State relations. To thoroughly investigate these issues, the ARC formed a study team under M.C. Setalvad. Based on the study team's report, the ARC finalized its own report in 1969, presenting 22 recommendations to enhance Centre-state relations.

Key recommendations included:

- Establishment of an Inter-State Council under Article 263 of the Constitution.

- Appointment of individuals with extensive experience in public life and administration, displaying a non-partisan attitude, as governors.

- Delegation of powers to the maximum extent to the states.

- Transfer of more financial resources to the states to reduce their dependency on the Centre.

- Deployment of Central armed forces in the states, either upon their request or otherwise.

Despite these recommendations, no action was taken by the Central government.

Rajamannar Committee

In 1969, the Tamil Nadu Government (DMK) formed a three-member committee, chaired by Dr. P. V. Rajamannar, to examine the entire issue of Centre-state relations and propose constitutional amendments to ensure maximum autonomy for the states. The committee submitted its report to the Tamil Nadu Government in 1971.

The committee identified reasons for the prevailing unitary trends (centralization tendencies) in the country, including certain provisions in the Constitution that grant special powers to the Centre, one-party rule at both the Centre and in the states, inadequacy of states' fiscal resources leading to dependence on the Centre for financial assistance, and the institution of Central planning and the role of the Planning Commission.

Key recommendations of the committee included:

- Immediate establishment of an Inter-State Council.

- Making the Finance Commission a permanent body.

- Disbanding the Planning Commission and replacing it with a statutory body.

- Omitting Articles 356, 357, and 365 (related to President's Rule).

- Omitting the provision that the state ministry holds office during the pleasure of the governor.

- Transferring certain subjects from the Union List and the Concurrent List to the State List.

- Allocating residuary powers to the states.

- Abolishing All-India services (IAS, IPS, and IFoS).

Despite these recommendations, the Central government completely ignored the Rajamannar Committee's suggestions.