Legal Current Affairs for CLAT (August 2024) | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

SCs/STs Sub-Classification Case

Why in News?

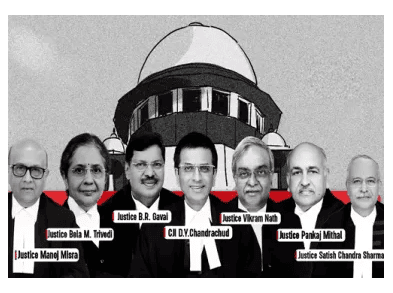

A seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court has upheld the sub-classification among Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) to ensure that the benefits of reservation reach the most marginalized sections within these groups. The bench comprised Chief Justice of India (CJI) Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud and Justices B.R. Gavai, Vikram Nath, Bela M. Trivedi, Pankaj Mithal, Manoj Misra, and Satish Chandra Sharma. The decision, delivered with a 6:1 majority, pertains to the case of State of Punjab And Ors. v. Davinder Singh And Ors.

Background of State of Punjab And Ors. v. Davinder Singh And Ors.

E.V. Chinnaiah v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2005)

- In this case, the Supreme Court invalidated the Andhra Pradesh Scheduled Castes (Rationalisation of Reservations) Act, 2000, which had sub-classified Scheduled Castes into four groups.

- The Court ruled that Scheduled Castes form a homogeneous class and cannot be further divided or sub-classified.

Origin of the Case

- The case arose from Punjab’s initiative to prioritize the Balmiki and Mazhabi Sikh communities within SC reservations.

- The Punjab Legislature enacted the Punjab Scheduled Castes and Backward Classes (Reservation in Services) Act, 2006, which allocated 50% of SC vacancies in direct recruitment as a first preference for Balmikis and Mazhabi Sikhs if candidates from these groups were available.

- The Punjab and Haryana High Court declared this provision unconstitutional.

Haryana Government Notification, 1994

- On November 9, 1994, Haryana issued a notification categorizing Scheduled Castes into two groups—Blocks A and B—for reservation purposes.

- This notification was later quashed by the Punjab and Haryana High Court.

Tamil Nadu Arunthathiyars Act, 2009

- This Act reserved 16% of SC seats in educational institutions for the Arunthathiyars community.

- The Act’s constitutional validity was challenged in the Supreme Court.

State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh (2020)

- On August 27, 2020, a Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court observed that the judgment in E.V. Chinnaiah needed reconsideration by a larger seven-judge bench.

- The Court noted that Chinnaiah had overlooked significant aspects of the issue of sub-classification within Scheduled Castes.

- This referral resulted in the present constitutional examination of the validity of sub-classification for affirmative action, including reservations.

Court’s Observations

- Issue 1: Is sub-classification of reserved classes permissible under Articles 14, 15, and 16?

- Held: Yes. Sub-classification under Articles 15(4) and 16(4) must be based on a rational criterion reflecting social backwardness among the sub-groups.

- Issue 2: Are Scheduled Castes homogeneous or heterogeneous?

- Held: Scheduled Castes are not a homogeneous group. Their identification under the Constitution acknowledges internal heterogeneity.

- Issue 3: Does Article 341 create a homogeneous class through deeming fiction?

- Held: While Article 341 creates a deeming fiction to designate certain castes as Scheduled Castes, it does not establish a unified, indivisible group that cannot be sub-classified. It merely groups specified castes or sub-castes as Scheduled Castes.

- Issue 4: Are there limits on sub-classification?

- Held: Sub-classification for reservation must adhere to constitutional limits.

- States may adopt:

- Preference Model: Prioritizing certain sub-castes for reserved seats.

- Exclusive Model: Reserving seats specifically for certain sub-castes.

Majority’s Opinion

CJI D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice Manoj Misra:

- Article 14 allows sub-classification within a class if the class is not homogeneous for the purpose of the law.

- Sub-classification is not confined to Other Backward Classes (OBCs) but also applies to beneficiary classes under Articles 15(4) and 16(4).

- Article 341(1) does not create a legal fiction that Scheduled Castes constitute a homogeneous class.

- The Chinnaiah judgment, which prohibited sub-classification of Scheduled Castes, is overruled.

- States must collect data on the inadequate representation of groups in state services as evidence of backwardness.

- Article 335 does not constrain the powers under Articles 16(1) and 16(4) but emphasizes the need to consider SC/ST claims in public services.

Justice B.R. Gavai:

- The State must demonstrate that the group receiving preferential treatment is inadequately represented compared to other castes within the Scheduled Castes list.

- Such justification must rely on empirical data showing the inadequate representation of the sub-class.

- The State cannot reserve 100% of the seats for a particular sub-class within the Scheduled Castes to the exclusion of others on the list.

- Sub-classification is permissible only when reservations are made for both the sub-class and the larger class.

Justice Vikram Nath:

- Justice Vikram Nath agrees with the views of CJI D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice B.R. Gavai.

Justice Pankaj Mithal:

- Justice Mithal concurs with the opinions of CJI D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice B.R. Gavai that sub-classification within Scheduled Castes is constitutionally valid.

- He supports Justice B.R. Gavai’s view that the ‘creamy layer’ principle should apply to SCs and STs.

Recommendations:

- Re-evaluation of Reservation Policies: Suggests a comprehensive review of reservation policies and the exploration of alternative methods to uplift disadvantaged groups without dismantling the current system until a new framework is ready.

- Limitation of Reservation: Advocates limiting reservations to the first generation of beneficiaries, excluding subsequent generations if the family has attained higher socio-economic status.

- Periodic Review: Proposes regular assessments to exclude individuals or families who have progressed and no longer require reservation benefits.

Justice Satish Chandra Sharma:

- Justice Sharma concurs with the opinions of CJI D.Y. Chandrachud and Justice B.R. Gavai that sub-classification within Scheduled Castes is constitutionally permissible.

- He aligns with Justice B.R. Gavai’s view on the applicability of the ‘creamy layer’ principle.

Who gave Dissenting Opinion in Sub-Classification Case?

Justice Bela M. Trivedi's Lone Dissenting Opinion in the SC/ST Sub-Classification Case

Constitutional Framework:

- The Presidential List specifying "Scheduled Castes" under Article 341 attains finality once the notification is published.

- Only Parliament has the authority to include or exclude castes from the Scheduled Castes list as notified under Article 341(1).

- States lack legislative competence to sub-classify or regroup castes enumerated as Scheduled Castes in the Article 341 notification.

Homogeneous Nature of Scheduled Castes:

- Although the Scheduled Castes are drawn from different castes and tribes, they gain a special status solely through the Presidential notification under Article 341.

- The historical and social background of "Scheduled Castes" renders them a homogeneous class that states cannot alter.

Limits on State Powers:

- States cannot modify the Presidential List or interfere with Article 341 under the pretext of reservation or affirmative action.

- Any attempt by states to sub-classify Scheduled Castes is unconstitutional.

Limits of Article 142 Powers:

- Article 142 cannot be invoked to create a new structure by disregarding explicit constitutional provisions.

- Even if well-intentioned, the Supreme Court cannot validate state actions that contravene the Constitution.

Conclusion:

- The legal principles established in the E.V. Chinnaiah case are correct and should be upheld.

- States have no authority to sub-classify Scheduled Castes as notified under Article 341.

What is the Journey of Caste Based Reservation in India?

Historical Background of Caste Discrimination

- Caste discrimination in India was historically extreme, often considered more severe than racial discrimination or slavery in other parts of the world.

- Lower castes were subjected to inhumane treatment for centuries, deprived of fundamental rights such as education and access to basic necessities like water.

- Social reformers, notably Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, spearheaded movements like the Mahad Satyagraha to advocate for the rights and dignity of marginalized communities.

Constitutional Provisions for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

- Articles 341 and 342: Enable the identification of Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) through Presidential notifications.

- Articles 15 and 16: Permit reservations and other special provisions to promote the socio-economic and educational advancement of SCs and STs.

- Article 46: Mandates the state to focus on improving the educational and economic status of weaker sections, with a special emphasis on SCs and STs.

Introduction of the Creamy Layer Concept

- Initially, the "creamy layer" exclusion principle was not applied to SCs and STs, as established in the Indra Sawhney case.

- Subsequent rulings, such as those in M. Nagaraj and Jarnail Singh cases, extended the creamy layer criterion to SCs and STs, aiming to ensure that the most disadvantaged among these groups benefit from affirmative action.

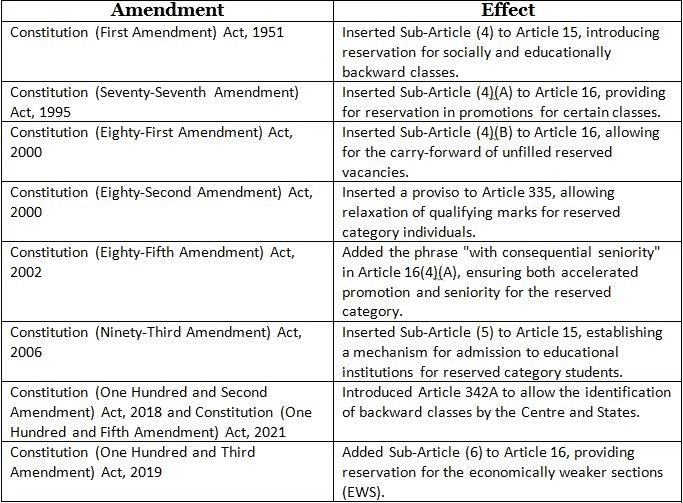

What are the Major Amendments Related to Reservation?

Table:

What are the Key Cases on Reservation in India?

State of Madras v. Champakam Dorairajan (1951)

- The Supreme Court ruled that caste-based reservations in educational institutions violated Article 29(2) of the Constitution.

B. Venkataramana v. State of Madras (1951)

- The Court declared caste-based reservations in public services unconstitutional under Articles 16(1) and 16(2).

M.R. Balaji v. State of Mysore (1963)

- The Supreme Court set a 50% limit on reservations and held that excessive reservations violated Article 15(4).

T. Devadasan v. Union of India (1964)

- The Court invalidated the carry-forward rule for unfilled reserved vacancies, asserting that it violated the principles of equal opportunity.

State of Kerala v. N.M. Thomas (1976)

- The Court upheld the relaxation in qualifying marks for SC/ST candidates, moving towards an interpretation of substantive equality.

Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992)

- A landmark decision that upheld reservations for OBCs but ruled against reservations in promotions. It also reaffirmed the 50% cap on total reservations.

Union of India v. Virpal Singh Chauhan (1995)

- Introduced the catch-up rule for general category candidates in promotions.

Ajit Singh Januja v. State of Punjab (1996)

- The Court emphasized balancing reservations with administrative efficiency, reinforcing the catch-up rule.

S. Vinod Kumar v. Union of India (1996)

- Held that relaxation in qualifying marks for promotions for SC/ST candidates violated the equality principle.

M. Nagaraj v. Union of India (2006)

- Upheld constitutional amendments allowing reservations in promotions with consequential seniority, provided they don’t negatively impact administrative efficiency.

Ashok Kumar Thakur v. Union of India (2008)

- Upheld the 27% reservation for OBCs in higher education, but excluded the creamy layer from its scope.

BK Pavitra (II) v. State of Karnataka (2019)

- The Court upheld the consequential seniority for SC/ST employees in promotions, reinforcing the principle of substantive equality.

Jarnail Singh v. Lachhmi Narain Gupta (2018)

- Reiterated the need to exclude the creamy layer among SC/ST for reservation benefits.

Maratha Quota Case (Dr. Jaishri Laxmanrao Patil v. Chief Minister, Maharashtra) (2021)

- The Supreme Court struck down Maharashtra’s law granting reservations to the Maratha community, ruling that it violated the 50% cap set by Indra Sawhney.

Neil Aurelio Nunes v. Union of India (2022)

- The Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the reservation system, reinforcing the principle of substantive equality.

Dissent in SC/ST Sub-classification Case

Why in News?

Recently, a seven-judge bench of the Supreme Court in the case of State of Punjab and Ors. v. Davinder Singh and Ors. allowed states to sub-classify Scheduled Castes (SCs) in order to provide separate quotas for more backward groups within the SC category. However, Justice Trivedi dissented, expressing the view that such sub-classification interferes with the Presidential list of SCs under Article 341, which can only be modified by Parliament. She raised concerns that sub-classification could introduce political factors into the SC-ST list, potentially undermining its original intent of preventing political influence.

Background of the Case: State of Punjab and Ors. v. Davinder Singh and Ors.

- The case stemmed from Punjab’s efforts to provide preferential treatment to certain communities within the SC reservations. In 2006, the Punjab Legislature enacted the Punjab Scheduled Castes and Backward Classes (Reservation in Services) Act. Section 4(5) of the Act mandated that 50% of vacancies within the SC quota for direct recruitment should be reserved for Balmikis and Mazhabi Sikhs, if available, as a first preference among SC candidates.

- However, the Punjab and Haryana High Court struck down this provision in 2010, relying on the Supreme Court’s judgment in E.V. Chinnaiah v. State of Andhra Pradesh (2005). The E.V. Chinnaiah judgment had held that the Scheduled Castes form a homogeneous group and cannot be further sub-divided or sub-classified.

- Similar attempts at sub-classification had been made by other states:

- In 1994, Haryana issued a notification classifying SCs into two categories (Blocks A and B) for reservation purposes.

- In 2009, Tamil Nadu passed the Arunthathiyars Act, allocating 16% of SC reserved seats in educational institutions to Arunthathiyars.

- These attempts at sub-classification were challenged in various courts, citing the E.V. Chinnaiah judgment. The matter eventually reached the Supreme Court in the case of State of Punjab v. Davinder Singh. On August 27, 2020, a five-judge Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court held that the E.V. Chinnaiah judgment needed to be reconsidered by a larger bench. The Court observed that the E.V. Chinnaiah judgment had failed to consider important factors related to sub-classification within Scheduled Castes.

- This referral led to the formation of a seven-judge Constitution Bench to examine the validity of sub-classification within Scheduled Castes for affirmative action and reservations. The seven-judge bench was tasked with addressing two key issues:

- Whether sub-classification within reserved castes should be permitted.

- The correctness of the E.V. Chinnaiah decision, which held that SCs notified under Article 341 form one homogeneous group that cannot be further sub-categorized.

- The case has attracted significant attention due to its potential to impact reservation policies and the interpretation of constitutional provisions related to Scheduled Castes.

What were the Court’s Observations?

- Justice Bela Trivedi, in her dissent, emphasized that the list of Scheduled Castes notified by the President under Article 341 cannot be altered by the States.

- The Presidential List of Scheduled Castes, once notified under Article 341 of the Constitution, becomes final and cannot be modified by the States.

- Only Parliament, through legislation, holds the power to include or exclude any caste, race, tribe, or group from the Scheduled Castes list as specified in the Presidential notification under Article 341(1).

- The rule of plain meaning, or literal interpretation, must be followed while interpreting constitutional provisions, though with a broad and generous approach.

- Scheduled Castes, despite originating from various castes, races, or tribes, achieve a homogeneous class status due to the Presidential notification under Article 341, and this cannot be altered by State actions.

- States lack the legislative competence to enact laws that provide reservation or preferential treatment to specific castes by subdividing, sub-classifying, or regrouping the Scheduled Castes listed in the Presidential notification.

- Any effort by the States to alter the Presidential List or manipulate Article 341 under the pretext of providing reservation or affirmative action for weaker sections is ultra vires the Constitution.

- The precedent established in the E.V. Chinnaiah case, considered by a Constitution Bench and taking into account prior judgments like Indra Sawhney, should not have been questioned or referred to a larger bench without valid reasons, in accordance with the doctrines of precedent and stare decisis.

- The Supreme Court’s power under Article 142 cannot be used to validate State actions that contradict explicit constitutional provisions, even if such actions are well-intended or affirmative in nature.

- Affirmative action and legal frameworks, while aimed at creating a more equitable society, must align with complex legal principles to ensure fairness and constitutionality.

- The law laid down in the E.V. Chinnaiah case by the Five-Judge Bench is considered the correct interpretation of Article 341 and should be upheld.

Who are Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes?

- The Constitution does not specifically define who belongs to the Scheduled Castes (SC) or Scheduled Tribes (ST).

- However, Articles 341 and 342 empower the President to create a list of these castes and tribes.

- Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes are those castes or tribes that the President may specify through a public notification.

- If such a notification pertains to a State, it must be issued after consulting the Governor of that State.

- Any additions or deletions from the list of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes can be made by Parliament through legislation.

- In case of any dispute regarding whether a particular tribe qualifies as a Scheduled Tribe under this Article, the public notification issued by the President under Article 341(1) must be referred to.

- The Constitution provides special provisions to protect the interests of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes.

Legal Provisions:

- Article 341 of the Indian Constitution addresses the list of Scheduled Castes.

- Article 341(1): The President, with respect to any State or Union Territory, and in the case of a State, after consulting its Governor, may by public notification specify the castes, races, or tribes, or parts or groups within castes, races, or tribes, which shall be considered Scheduled Castes for the purposes of this Constitution in relation to that State or Union Territory.

- Article 341(2): Parliament has the authority to include or exclude any caste, race, or tribe from the list of Scheduled Castes specified in a notification issued under clause (1). However, once a notification is issued under clause (1), it cannot be altered by any subsequent notification unless modified by law passed by Parliament.

What is Article 142 of Indian Constitution?

- Article 142 of the Indian Constitution grants the Supreme Court of India the authority to issue orders or decrees necessary to do complete justice in matters before it. This provision allows the Supreme Court to take extraordinary steps, beyond what is explicitly laid out in the law, to ensure justice is served. Key points about Article 142 include:

- Supreme Court's Authority: The Court can issue any decree or order deemed necessary for delivering complete justice in the cases it handles.

- Enforceability: These decrees or orders are enforceable throughout India.

- Methods of Enforcement: The manner of enforcement may be determined by law passed by Parliament or, if no such law exists, by a presidential order.

- Supreme Court's Jurisdiction:The Court has jurisdiction over the entire territory of India and can:

- Secure the attendance of any person.

- Order the discovery or production of documents.

- Investigate or punish contempt of the Court.

- Limits: While the powers of the Supreme Court under this article are broad, they are still subject to laws enacted by Parliament.

- In essence, Article 142 gives the Supreme Court vast discretion to ensure that justice is fully realized, even in situations where existing laws may not directly provide a solution. However, this power is not without limits and is subject to the legislative framework established by Parliament.

What are the Constitutional Provisions Governing Reservation in India ?

- Part XVI of the Constitution deals with the reservation of seats for Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in Central and State legislatures.

- Articles 15(4) and 16(4) of the Constitution empower both the State and Central Governments to reserve seats in government services for SCs and STs.

- The Constitution was amended by the Constitution (77th Amendment) Act, 1995, which inserted a new clause (4A) in Article 16, enabling the government to provide reservation in promotions for SCs and STs.

- Later, clause (4A) was modified by the Constitution (85th Amendment) Act, 2001, to grant consequential seniority to SC and ST candidates promoted through reservation.

- The Constitution (81st Amendment) Act, 2000, inserted Article 16(4B), which allows the state to fill unfilled vacancies reserved for SCs and STs from the previous year in the following year, thereby bypassing the 50% reservation ceiling on total vacancies for that year.

- Article 330 and 332 provide specific representation through reservation of seats for SCs and STs in the Parliament and State Legislative Assemblies, respectively.

- Article 243D mandates reservation of seats for SCs and STs in every Panchayat.

- Article 233T provides for reservation of seats for SCs and STs in every Municipality.

- Article 335 states that the claims of SCs and STs should be considered with due regard to the maintenance of administrative efficiency.

Citizenship of Child

Why in News?

The Bombay High Court in Goa ruled that a child cannot be denied Indian citizenship or a passport solely because they live with a single parent who holds foreign nationality. The court concluded that the child’s Indian citizenship, acquired by birth, remains valid even if the parent changes their nationality. This decision overturned the Indian High Commission’s refusal to renew the child’s passport. Justices Makarand Karnik and Valmiki S.A. Menezes presided over the case Chrisella Valanka Kushi Raj Naidu v. Ministry of External Affairs.

Background of Chrisella Valanka Kushi Raj Naidu v. Ministry of External Affairs:

- The petitioner, Chrisella Valanka Kushi Raj Naidu, was born in Goa, India, on 27th October 2007, to Indian citizen parents.

- When she was about 3 years old, her father abandoned both her and her mother.

- In 2019, the petitioner’s mother was granted a divorce by court order.

- In 2015, the petitioner’s mother registered her birth in Portugal and acquired Portuguese citizenship due to employment opportunities abroad.

- The petitioner and her mother then moved to the United Kingdom, where the mother worked and the petitioner attended school.

- In 2014, the petitioner was issued an Indian passport, which was valid until 2nd December 2019.

- In 2019, the petitioner’s mother applied for the renewal of the Indian passport through the Indian High Commission in the UK.

- However, on 5th August 2020, the Indian High Commission refused to renew the passport, citing that the petitioner was not eligible for renewal because she was a minor child living with a single parent who held foreign nationality.

- The petitioner, through her mother as natural guardian, challenged this decision by filing a writ petition in the Bombay High Court.

- The case raised significant questions regarding the citizenship status of a minor child born in India to Indian parents, where one parent later acquired foreign citizenship and had sole custody of the child.

What were the Court’s Observations?

- The court ruled that, in accordance with Section 3(1)(c) of the Citizenship Act, 1955, the petitioner acquired Indian citizenship by birth, as she was born in India after the enactment of the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2003, to parents who were Indian citizens at the time of her birth.

- The bench observed that the petitioner’s Indian citizenship has not been revoked or ceased under Sections 8, 9, or 10 of the Citizenship Act, 1955. The mere fact that a parent has acquired foreign citizenship does not result in the termination of the child’s Indian citizenship.

- The court noted that Section 9 of the Citizenship Act, which addresses the termination of citizenship due to voluntary acquisition of foreign citizenship, does not include any provision for the termination of citizenship of minors whose parents have acquired foreign nationality.

- The bench found that the Office Memorandum dated 31st July 2024, cited by the respondents, actually supports the petitioner’s case, as it clarifies that the citizenship of minor children remains unaffected if a parent voluntarily acquires citizenship of another country.

- The court held that the Passport Officer’s refusal to issue a passport was unjustifiable under Section 6 of the Passports Act, 1967, as none of the specified grounds for refusal applied to the petitioner’s case.

- The judges emphasized that a child cannot be rendered stateless, and the acquisition of foreign nationality by the petitioner’s mother does not affect the petitioner’s Indian citizenship, as the petitioner acquired it by birth.

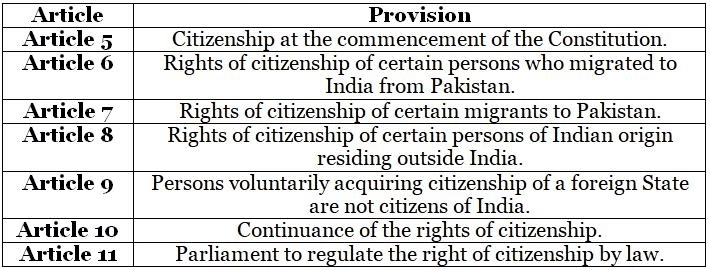

What are the Constitutional Provisions Concerning Citizenship in India?

- Part II of the Constitution of India, 1950, comprising Articles 5 to 11, governs the concept of citizenship.

- The Parliament of India has exclusive authority over matters related to citizenship, as these fall under the Union List in the Seventh Schedule.

- The constitutional provisions on citizenship primarily identify individuals who became citizens of India at the commencement of the Constitution on January 26, 1950.

- The Constitution does not provide detailed or permanent provisions regarding the acquisition or loss of citizenship after its commencement.

- Article 11 empowers the Parliament to legislate on matters of citizenship not specifically addressed in the Constitution.

- In compliance with this mandate, the Parliament enacted the Citizenship Act, 1955, which has been amended over time.

- The Citizenship Act, 1955, along with its amendments, outlines the legal framework for matters related to the acquisition, termination, and regulation of Indian citizenship.

- The constitutional provisions on citizenship are not exhaustive and depend on parliamentary legislation for a comprehensive framework on citizenship laws.

Legal Provisions on Citizenship

What is the Citizenship Act, 1955?

- Citizenship rights in India were established after the nation’s independence in 1947.

- Before independence, under British rule, citizenship rights were not granted to Indians.

- The British Citizenship and Alien Rights Act of 1914, which applied during the pre-independence era, was repealed in 1948.

- Under the British Nationality Act, Indians were classified as British subjects but did not have citizenship rights.

- The partition of India in 1947 led to large-scale migration across the newly created borders between India and Pakistan.

- Following the partition, individuals were given the right to choose their country of residence and acquire citizenship accordingly.

- The Constituent Assembly of India, considering these conditions, restricted the scope of citizenship provisions in the Constitution to address the immediate need for determining citizenship status for migrants.

- The Citizenship Act, 1955, enacted by Parliament, laid down specific provisions regarding the requirements and eligibility for acquiring citizenship.

- The Citizenship Act, 1955 governs the acquisition and termination of citizenship after the commencement of the Constitution.

- Initially, the Citizenship Act, 1955 included provisions for Commonwealth Citizenship.

- The Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2003 repealed the provisions regarding Commonwealth Citizenship from the original Citizenship Act, 1955.

- The Citizenship Act of 1955 prescribes five ways of acquiring citizenship:

- By birth,

- By descent,

- By registration,

- By naturalisation,

- By incorporation of territory.

- The Act does not provide for dual citizenship or dual nationality.

- Citizenship is granted only through the aforementioned provisions, i.e., by birth, descent, registration, naturalisation, or territorial incorporation.

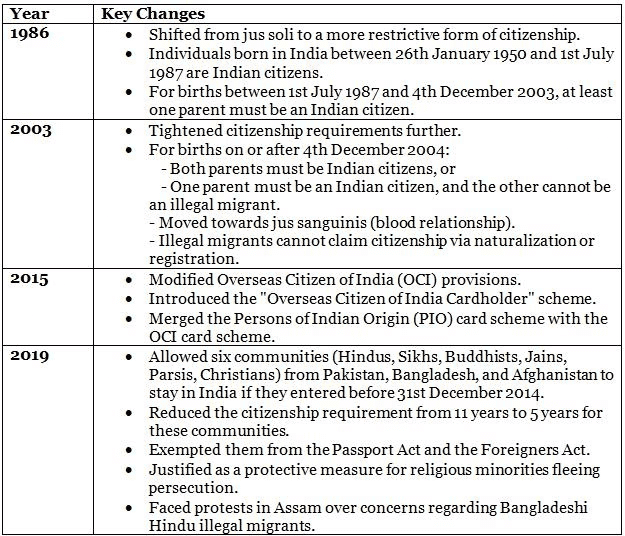

- The Act has been amended several times — in 1986, 1992, 2003, 2005, 2015, and 2019. These amendments have progressively narrowed the broader and more universal principles of citizenship based on birth.

- The Foreigners Act places a significant burden on individuals to prove that they are not foreigners.

Acquisition of Indian Citizenship

By Birth

Section 3 outlines who is considered an Indian citizen by birth:

- Anyone born in India between January 26, 1950, and July 1, 1987.

- Anyone born in India between July 1, 1987, and December 3, 2004, if at least one parent was an Indian citizen.

- Anyone born in India on or after December 3, 2004, if both parents are Indian citizens or if one parent is an Indian citizen and the other is not an illegal migrant.

By Descent

Section 4 governs citizenship by descent:

- A person born outside India on or after January 26, 1950, may be considered a citizen by descent if their father was an Indian citizen at the time of their birth.

- For those born on or after December 10, 1992, either parent being an Indian citizen is sufficient.

By Registration

- Section 5 provides for citizenship by registration for specific groups, such as people of Indian origin, spouses of Indian citizens, and minor children of Indian citizens.

By Naturalization

- Section 6 allows for citizenship by naturalization for foreigners who have resided in India for at least 12 years.

- Section 6A outlines special provisions for citizenship under the Assam Accord.

- Section 6B (added in 2019) provides a pathway to citizenship for certain persecuted minorities from Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and Pakistan who entered India before December 31, 2014.

By Incorporation of Territory

- If India acquires new territory, the people in that territory automatically become Indian citizens.

- Following the integration of Goa, Daman & Diu from Portuguese control, anyone born before December 20, 1961, in these regions, or whose parents or grandparents were born there, is considered an Indian citizen under the Goa, Daman, and Diu (Citizenship) Order, 1962.

- Sections 7A-7D address the Overseas Citizenship of India, including eligibility, rights, and cancellation conditions.

How Indian Citizenship Can Be Revoked

Renunciation of Citizenship

- Section 8 allows voluntary renunciation of Indian citizenship.

- A person who renounces Indian citizenship in order to acquire the citizenship of another country ceases to be an Indian citizen.

- Upon renunciation of citizenship by a father, his minor children will also lose their Indian citizenship.

- A minor child who loses Indian citizenship under these circumstances can reclaim it within one year of reaching the age of majority.

Termination of Citizenship

- Section 9 states that Indian citizenship is automatically terminated if a person acquires the citizenship of another country.

- The Government of India has the authority to terminate the citizenship of any Indian citizen who voluntarily acquires the citizenship of a foreign country.

- In the case of Bhagwati Prasad v. Rajeev Gandhi (1986), the court held that the Central Government, not the High Court, has the power to decide issues related to Section 9 of the Act.

- The legal principles set out in Bhagwati Prasad v. Rajeev Gandhi (1986) were later affirmed in Madhya Pradesh v. Peer Mohd. & Anr. (1963) and Hari Shankar v. Sonia Gandhi (2001) concerning the interpretation of Section 9 of the Act.

Deprivation of Citizenship

- Section 10 allows the government to revoke a person’s Indian citizenship under certain conditions.

- The Government of India may deprive any person of their Indian citizenship if the citizenship was obtained through:

- Registration

- Naturalization

- Application of Article 5(c) of the Constitution of India

- Article 5(c) of the Constitution refers to citizenship at the commencement of the Constitution for individuals domiciled in India who have been ordinarily resident in India for at least five years before the commencement of the Constitution.

What are the Amendments made in Citizenship Law

Freedom of Speech and Expression not Absolute

Why in the News?

The Bombay High Court recently addressed the case of Arijit Singh v. Codible Ventures LLP, where it restricted third parties from exploiting Bollywood singer Arijit Singh’s personality rights—such as his voice, likeness, and signature—without his consent. This ruling underscores the legal response to the rising issue of unauthorized use of celebrities’ attributes by AI content creators, emphasizing concerns about privacy and intellectual property in the digital age.

Background of Arijit Singh v. Codible Ventures LLP:

- Arijit Singh, a prominent Indian singer with significant celebrity status, filed a suit in the Bombay High Court seeking the protection of his personality rights and right of publicity against unauthorized commercial exploitation by various defendants.

- The defendants are accused of engaging in the following activities:

- Creating AI voice models that replicate Singh’s voice without permission.

- Producing and distributing tutorials on how to replicate Singh’s voice using AI.

- Selling merchandise bearing Singh’s name, image, and likeness without authorization.

- Falsely claiming association with Singh for commercial events.

- Creating and sharing GIFs and other content featuring Singh’s image and persona.

- Registering domain names containing Singh’s full name.

- Singh contends that these activities violate his personality rights, right of publicity, and moral rights as a performer under the Copyright Act.

- He argues that the unauthorized use of his persona, particularly through AI voice cloning, risks economic harm to his career and reputation.

- The defendants argue that their use of AI technology to generate content, including songs and videos purportedly in Singh’s name, voice, image, and persona, does not constitute a breach of rights. They assert that the content is created in a transformative or non-commercial context, and their actions are not intended to harm Singh’s career but to explore technological advancements and creative expression within fair use.

- From the defendants’ perspective, the creation and commercialization of AI-generated content featuring Singh’s attributes is seen as an innovative use of technology, which they believe should be protected under the freedom of expression and creative freedom. They argue that intellectual property and personality rights should be interpreted in light of technological progress, potentially redefining permissible uses of AI-generated content.

- Singh sought an ex parte interim injunction against the defendants to stop further violations of his rights.

Court’s Observations

- The Court found that Singh has established his celebrity status and acquired valuable personality rights and the right of publicity.

- It observed that the unauthorized use of AI tools to replicate a celebrity’s voice constitutes a violation of that celebrity’s personality rights.

- The Court stated that such technological exploitation infringes upon an individual’s right to control their likeness and voice and undermines their ability to prevent commercial and deceptive uses of their identity.

- The Court expressed concern about the vulnerability of celebrities, particularly performers, to being targeted by unauthorized AI-generated content.

- It noted that the defendants were attracting visitors to their websites and AI platforms by exploiting Singh’s popularity and reputation, thereby subjecting his personality rights to potential abuse.

- The Court recognized that creating new audio or video content using Singh’s AI voice or likeness without consent could harm Singh’s career and livelihood.

- The Court highlighted that allowing continued unauthorized use of Singh’s persona risks economic damage and creates opportunities for misuse by malicious individuals.

- While freedom of speech allows for critique and commentary, the Court emphasized that it does not extend to exploiting a celebrity’s persona for commercial gain.

- The Court noted Singh’s conscious choice to refrain from brand endorsements and excessive commercialization of his personality traits in recent years.

- It found that the balance of convenience favored Singh, as he would suffer irreparable injury without the requested relief.

- The Court deemed it appropriate to grant a dynamic injunction to address potential future violations of Singh’s rights.

- Regarding certain infringing videos, rather than issuing a complete takedown, the Court decided that removing all references to Singh’s personality traits would suffice.

Why is Freedom of Speech and Expression Not Absolute?

- The fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression, enshrined in constitutional frameworks, is a cornerstone of democratic societies, empowering individuals to voice their opinions and engage in open discourse.

- This right, however, is not absolute and is subject to limitations and restrictions as outlined by law.

- The principle of freedom of speech must be balanced with other important interests and rights, such as privacy, intellectual property, and public order.

- Legal jurisdictions universally recognize that the exercise of free speech should be restrained by the potential harm and infringement upon others' rights.

- Although individuals are entitled to express their views, this right does not extend to actions that would constitute defamation, incitement to violence, or the unauthorized exploitation of personal attributes, including those of celebrities.

- Intellectual property and personality rights provide legal safeguards against the unauthorized use or exploitation of an individual’s persona, such as their name, likeness, voice, and other personal attributes.

- Courts consistently affirm that the right to free expression cannot be invoked to justify the unauthorized exploitation of personal attributes, underscoring the legitimacy and enforceability of personal rights and privacy protections.

- Judicial precedents confirm that freedom of speech and expression does not allow the violation of intellectual property rights or the commercial use of an individual’s persona without consent. These protections are vital in ensuring that the exercise of free speech does not infringe upon individuals' rights to control and profit from their personal and professional identity.

- In conclusion, while freedom of speech and expression is a fundamental and protected right, it is constrained by legal boundaries designed to protect other rights and interests. This balance ensures that the exercise of free expression does not undermine or violate the protected rights of individuals, including their personal and intellectual property rights.

What are the Legal Provisions Involved?

- Right to Freedom of Speech and Expression in India

The right to freedom of speech and expression is guaranteed under Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India.

The underlying philosophy of this Article is rooted in the Preamble of the Constitution, which pledges to secure liberty of thought and expression for all citizens. - Aspects Included in Article 19(1)(a):

- Freedom of the Press

- Freedom of Commercial Speech

- Right to Broadcast

- Right to Information

- Right to Criticize

- Right to Expression Beyond National Boundaries

- Right Not to Speak (Right to Silence)

- Essential Elements of Article 19(1)(a), COI:

- This right is available only to Indian citizens, not to foreign nationals.

- It includes the freedom to express one’s views and opinions on any matter through any medium, such as speech, writing, printing, pictures, films, movies, etc.

- While this right is fundamental, it is not absolute. The government is allowed to impose reasonable restrictions by law.

- Reasonable Restrictions Under Article 19(2):

Article 19(2) specifies that the freedom of speech and expression may be restricted for the following reasons:- Sovereignty and integrity of India

- Security of the State

- Friendly relations with foreign States

- Public order

- Decency or morality

- Contempt of court

- Defamation

- Incitement to an offence

- Judicial Interpretation and Evolution:

- The interpretation of these provisions has evolved over time, influencing the scope and limitations of free speech in India.

Landmark Cases

Shreya Singhal v. Union of India (2015):- The Supreme Court struck down Section 66A of the Information Technology Act, 2000, which criminalized sending “offensive” messages through communication services.

- The Court ruled that the provision was unconstitutionally vague and had a chilling effect on free speech.

- The judgment highlighted the importance of safeguarding online speech and set a high threshold for imposing restrictions on freedom of expression.

- However, the Court reaffirmed that freedom of speech is not an absolute right.

Subramanian Swamy v. Union of India (2016):

- The Supreme Court upheld the constitutional validity of criminal defamation laws.

- The Court emphasized that the right to free speech does not extend to harming another person’s reputation, which is protected under Article 21 of the Constitution.

- The concept of personality rights, including the right to publicity, was recognized by the Court as an extension of the right to privacy under Article 21.

ICC Development (International) Ltd. v. Arvee Enterprises (2003):

- The Delhi High Court acknowledged the commercial value of a celebrity’s identity and the necessity to protect it from unauthorized exploitation.

Special Leave Petitions (SLPs)

Why in News?

Justices Dipankar Datta and Prashant Kumar Mishra have issued a new practice direction concerning Special Leave Petitions (SLPs), effective from 20th August 2024. This direction mandates that any SLP seeking exemption from filing a certified copy of an impugned order must include:

- A receipt from the High Court confirming the request for the certified copy.

- A statement that the application for the copy is still valid.

- An undertaking to submit the certified copy promptly once received.

- This move is aimed at streamlining the process and ensuring the timely submission of necessary documents. The Supreme Court issued this direction in the case of Harsh Bhuwalka & Ors v. Sanjay Kumar Bajoria.

- Background of the Harsh Bhuwalka & Ors v. Sanjay Kumar Bajoria Case

- The case concerns a Supreme Court order issued on 5th August 2024 regarding the filing of SLPs.

- The issue arose from a situation where petitioners made a false statement to the Supreme Court regarding their application for a certified copy of an impugned High Court order.

- The petitioners claimed they had applied for the certified copy but had not received it from the High Court. However, they had never actually applied for the certified copy before filing their SLP.

- The petitioners only submitted an application for the certified copy after filing the SLP, following the Supreme Court's request for proof.

- This case brought attention to the broader issue of litigants frequently filing SLPs without submitting proper certified copies of impugned judgments/orders.

- Many litigants had been submitting applications for exemptions from filing certified copies, often accompanied by false or misleading statements.

- The Supreme Court noted that its previously lenient approach towards such exemption requests had led to a belief among litigants that false statements could be made without consequences.

- This prompted the Supreme Court to issue new practice directions regarding the filing of SLPs and the exemption requests for submitting certified copies.

Court’s Observations

- The Court observed with concern that the provisions of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, which require Special Leave Petitions to be accompanied by certified copies of impugned judgments and orders, were being frequently violated.

- The Court noted that its previous leniency towards applications for exemption from filing certified copies had created an impression among litigants that they could make false statements without facing any repercussions. This highlighted the need for stricter discipline in the filing process.

- As a result, the Supreme Court issued new practice directions governing the filing of SLPs and exemption applications, aiming to ensure substantial compliance with existing rules.

- The Court expressed concern over the common practice of litigants failing to apply for and obtain certified copies and instead attaching downloaded copies of impugned judgments and orders to their Special Leave Petitions.

- The Court remarked that the widespread acceptance of exemption applications without proper verification had led to a situation where litigants were rarely required to submit undertakings for the subsequent filing of certified copies after receipt from the High Court.

- The Court concluded that this situation was unsustainable and that substantial compliance with the rules was essential as long as they remained in force.

- The Court emphasized that despite the rules mandating certified copies with SLPs, these rules were often not adhered to or enforced effectively.

What is a Special Leave Petition?

- A Special Leave Petition (SLP) is a discretionary mechanism for appealing to the Supreme Court of India.

- It is outlined under Article 136 of the Constitution of India, 1950 (COI).

- SLPs can be filed against any judgment, decree, or order made by any court or tribunal in India, excluding those related to the Armed Forces.

- The Supreme Court can hear appeals for decisions where there is no direct right of appeal.

- Granting special leave is entirely at the Supreme Court's discretion.

- SLPs can be filed in both civil and criminal matters.

- These petitions are typically filed when there is a significant legal question or perceived miscarriage of justice.

- The Supreme Court has the authority to refuse granting leave without offering an explanation.

- If the Court grants leave, the petition is converted into an appeal.

- SLPs provide a last resort for seeking justice after all other legal avenues have been exhausted.

- For every SLP, the Supreme Court must first decide whether to grant or deny the requested Special Leave.

- The Supreme Court has also stated that the remedy under Article 136 (SLP) is a constitutional right, allowing the bar to be bypassed through the routes available under Articles 32, 131, and 136 of the Constitution.

- Article 32 provides constitutional remedies for the protection of rights through writs like Habeas Corpus, Mandamus, Prohibition, Certiorari, and Quo Warranto.

- Article 131 concerns the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court regarding disputes between the Centre and States, or between States.

Origin of SLP

- The term “special leave to appeal” in Article 136(1) of the Indian Constitution is derived from the Government of India Act, 1935.

- The 1935 Act used the term “special leave” in five provisions, particularly Sections 110, 205, 206, and 208.

- Section 110(b)(iii) prohibited legislative bodies from making laws that would infringe on the King’s prerogative to grant special leave to appeal, except where explicitly stated.

- Section 205(2) allowed appeals to the Federal Court based on wrongly decided substantial questions of law, without requiring special leave from the King-in-Council.

- The same section also prohibited direct appeals to the King-in-Council (Judicial Committee of the Privy Council), whether with or without special leave.

- Section 206(1)(b) gave the Federal Legislature the power to allow appeals to the Federal Court in certain civil cases, with the Federal Court granting special leave.

- Section 206(2) allowed for the abolition of direct appeals to the King-in-Council if provisions under Section 206(1) were enacted.

- Section 208 dealt with appeals to the King-in-Council, permitting some cases to be appealed without leave, and others with leave from the Federal Court or King-in-Council.

- The special leave granted by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council was referred to as “special leave.”

- This historical context from the 1935 Act provided the foundation for the concept of special leave in the Indian Constitution.

Filing of an SLP

- Special Leave Petitions (SLPs) can be filed under Article 136 of the Indian Constitution against any judgment, decree, or order issued by a High Court or tribunal within India.

Time Period

- SLPs must be filed within 90 days from the date of a High Court judgment, or within 60 days from the date of a High Court order that refuses to grant a certificate of fitness for appeal to the Supreme Court.

Who Can File an SLP?

- Any affected party may file a Special Leave Petition (SLP) against a judgment or order that denies a certificate to appeal to the Supreme Court.

- SLPs can be filed in civil, criminal, or other matters where a significant legal question exists or a serious injustice has occurred.

- The petitioner must provide a brief summary of the case's facts, issues, timeline, and legal arguments challenging the decision.

- After filing, the petitioner will have an opportunity to present their case to the Supreme Court.

- Depending on the merits, the Court may issue a notice to the opposing party, who must file a counter-affidavit.

- The Supreme Court will then decide whether to grant leave to appeal.

- If leave is granted, the case becomes a civil appeal and will be heard again by the Supreme Court.

- The SLP process offers a special permission for aggrieved parties to appeal any order from a court or tribunal within India to the Supreme Court.

Grounds for Filing an SLP

- Although the Constitution does not specify precise grounds, SLPs are commonly filed on the following grounds:

- Substantial question of law

- Gross miscarriage of justice

- Violation of natural justice principles

- Violation of fundamental rights

Procedure for Filing an SLP

- An SLP must include all relevant facts upon which the Supreme Court will base its decision, in accordance with the grounds for filing.

- The petition must be signed by an Advocate-on-Record, in line with the Supreme Court Rules.

- The petitioner must include a statement affirming that no other petition on the same issue has been filed in any High Court.

- After the petition is filed, the Supreme Court will grant a hearing to the aggrieved party.

- Based on the merits of the case, the Court may allow the opposing party to present their case through a counter-affidavit.

- After hearing both parties, the Court will decide whether the case warrants further attention.

- If the Court deems the case suitable for further hearing, it will grant leave to appeal.

- If the Court finds insufficient grounds for further consideration, the petition will be rejected.

- The decision to grant or reject an SLP is solely at the discretion of the Supreme Court, based on the facts and arguments presented during the initial hearing.

- The procedure for filing and considering SLPs is designed to allow the Supreme Court to exercise its extraordinary jurisdiction under Article 136 of the Constitution judiciously.

Legal Provision

- Article 136 of the Constitution of India addresses special leave to appeal to the Supreme Court.

- It states:

- Not with standing anything in this Chapter, the Supreme Court may, at its discretion, grant special leave to appeal from any judgment, decree, determination, sentence, or order in any cause or matter passed by any court or tribunal in India.

- Clause (1) does not apply to judgments, determinations, sentences, or orders made by any court or tribunal established under laws concerning the Armed Forces.

Case Laws

- In Laxmi & Co. v. Anand R. Deshpande (1972), the Supreme Court ruled that when considering appeals under Article 136, it may take into account subsequent developments to expedite proceedings, protect parties' rights, and advance justice.

- In Kerala State v. Kunhayammed (2000), the Court clarified that its discretion to grant SLPs does not activate its appellate jurisdiction if leave is denied based on its findings.

- In Pritam Singh v. The State (1950), the Court ruled that the Supreme Court should not interfere with High Court decisions unless in exceptional cases. If an appeal is admitted, the appellant may challenge incorrect legal determinations by the High Court. The Court should apply consistent criteria when granting leave to appeal.

- In N. Suriyakala v. A. Mohandoss & Ors. (2007), the Court affirmed that Article 136 does not create an ordinary appellate jurisdiction but grants broad discretionary powers to the Supreme Court to intervene in the interests of justice, rather than conferring a right of appeal to litigating parties.

What is the Scope and Limitation of Article 136 of the COI?

- Article 136 of the Constitution of India grants the Supreme Court a broad discretionary power to grant special leave to appeal from any judgment, decree, determination, sentence, or order in any cause or matter made by any court or tribunal within the territory of India.

- The non-obstante clause in Article 136 highlights that this power overrides any restrictions on the Court’s appellate jurisdiction.

- The scope of this power covers both final and interlocutory orders and extends to tribunals exercising quasijudicial authority.

- It is important to note that Article 136 does not provide a right to appeal; instead, it grants the right to apply for special leave, which, if granted, may still be revoked.

- The Supreme Court has self-imposed restrictions on entertaining special leave petitions in criminal cases, especially those with concurrent findings of fact, except in exceptional cases such as cases of perversity, impropriety, violation of natural justice, or errors of law or record.

- The Court typically uses its power under Article 136 in exceptional circumstances, particularly when a question of law of general public importance arises.

- The Supreme Court has consistently refrained from limiting its discretionary power by establishing rigid principles or rules for the exercise of its jurisdiction under Article 136.

- In the case of Dhakeshwari Cotton Mills Ltd. v. Commissioner of Income Tax, West Bengal (1954), the Constitutional Bench observed that the limitations on the exercise of this discretionary jurisdiction are inherent in the nature and character of the power itself.

- The Court has emphasized that this exceptional and overriding power must be used sparingly and with caution, only in special and extraordinary circumstances.

- The Supreme Court has made it clear that no technical barriers can obstruct the exercise of this power when it finds that a person has been treated arbitrarily or denied a fair opportunity by a court or tribunal within India.

- In Mathai Joby v. George (2016), the Constitution Bench reaffirmed the expansive scope of Article 136, stating that efforts should not be made to limit the Supreme Court's powers under this Article, and instead, the power should be used judiciously and with circumspection.

Principle of Denying Relief

Why in News?

The Bombay High Court recently underscored that delays and laches could affect the admissibility of Public Interest Litigations (PIL). In a case where petitioners sought the cancellation of land allotment and an inquiry into alleged irregularities, the court emphasized that without an explanation for the delay in filing the PIL, it could refuse to exercise its discretionary power under Article 226 of the Constitution of India, 1950 (COI). This highlights the importance of timely filing and the court’s discretion in PIL matters. The division bench, comprising Chief Justice Devendra Kumar Upadhyaya and Justice Amit Borkar, heard the case of Govind Kondiba Tanpure & ors. v. The State of Maharashtra & ors.

Background of Govind Kondiba Tanpure & Ors. v. The State of Maharashtra & Ors.

- The case pertains to land in Gat No. 237 in the village of Dhangawadi, Taluka Bhor, District Pune, covering an area of 14 hectares and 35 ares.

- In 1993-1994, portions of this land were reserved for a Muslim burial ground and allotted to the Divisional Engineer, Telephones.

- In December 1994, the District Collector approved a scheme reserving 2 hectares 92 ares for Scheduled Castes and Tribes under a Village Extension Scheme.

- In 1995, 110 plots were demarcated but not handed over.

- In May 1994, respondent No. 4, Anantrao N. Thopate, applied for land allotment for educational purposes, which was initially rejected.

- In June 1999, the State Government allotted 2 hectares 90 ares to respondent No. 5, an educational trust, for educational purposes at a nominal rent.

- In 2008, the land use was modified to include Engineering and Management studies.

- An additional 5 hectares 40 acres was allotted in November 2008.

- Respondent No. 5, Rajgad Dnyanpeeth, constructed educational buildings on the land after taking possession in 2000 and 2009.

- The petitioners filed a Right to Information (RTI) application and subsequently filed this PIL in August 2013, challenging the allotments.

- The petition was registered in March 2015 and first circulated in court in January 2018.

- The petitioners alleged irregularities in the allotment process and breach of lease conditions by respondent No. 5, particularly regarding the mortgaging of the land.

- The petitioners then filed the present PIL challenging these actions.

What were the Court’s Observations?

- The principle of denying relief based on laches is also applicable to public interest litigation (PIL), and unexplained delay or laches can lead to the dismissal of PILs.

- The writ jurisdiction under Article 226 of the Constitution of India is discretionary, and the Court may refuse to exercise this jurisdiction if a petitioner approaches after an unexplained delay.

- The Court is not bound to assess the adequacy of an explanation for condoning delay or laches if no explanation has been provided by the petitioners.

- In situations where intervening would be unfair or unjust due to actions taken during the delay, the Court may deny relief even if the petitioners have a strong case on merits.

- The Court must weigh the length of the delay and the nature of actions taken during the delay when deciding whether to grant or deny relief, balancing the interests of justice.

- When one party’s conduct or neglect has placed the other party in a position where it would be unreasonable to return to their original state, the lapse of time and delay become significant factors in denying relief.

What is the Principle of Denying Relief?

- Courts of equity may deny relief to a plaintiff who has unreasonably delayed in asserting their rights, particularly when such delay has caused prejudice to the opposing party.

- This principle is based on the maxim "equity aids the vigilant, not those who slumber on their rights."

- The court may refuse to grant equitable remedies if the plaintiff's delay has led to a change in circumstances that would make the requested relief unjust or inequitable.

- The denial of relief is founded on the idea that parties should not benefit from their own negligence or inaction.

- This principle serves to protect defendants from unfair prejudice that may result from pursuing stale claims.

- The court’s decision to deny relief based on laches is influenced by the totality of circumstances, such as the duration of the delay, the reasons for it, and any harm to the defendant.

- The application of this principle is not solely reliant on the passage of time but is based on an equitable assessment of the parties' conduct and the risk of injustice.

- In applying this principle, courts seek to preserve the integrity of the legal process and discourage parties from delaying their claims to the disadvantage of others.

What is the Doctrine of Laches?

The doctrine of laches is a legal principle that prevents a party from seeking equitable relief if they have unreasonably delayed in asserting their rights, resulting in prejudice to the opposing party.

Key Elements:

- It bars relief when a claimant has delayed unreasonably in asserting their rights.

- The delay must have caused prejudice to the other party.

- Courts apply this doctrine to ensure fairness and to prevent the filing of stale claims.

- Unlike statutes of limitations, laches is a flexible doctrine applied at the discretion of the court.

- It is typically invoked in cases seeking equitable remedies, but its application has expanded in some jurisdictions.

Meaning of the Doctrine of Laches:

- Derived from the Latin word laxare, meaning "to lose," the doctrine traditionally refers to the failure to meet legal obligations due to negligence.

- In legal terms, laches refers to the failure to assert or exercise a legal right within a reasonable timeframe.

- It is based on the Latin maxim Vigilantibus Non Dormientibus Aequitas Subvenit, meaning "Equity aids the vigilant, not those who slumber on their rights."

- The principle states that courts of equity will not grant relief to parties who have been negligent in pursuing their legal claims, preferring those who have acted diligently in safeguarding their rights.

- A litigant can be deemed to have committed laches if they seek judicial intervention after an unreasonable or prejudicial delay in initiating legal proceedings.

- The laches doctrine promotes the timely resolution of disputes and prevents stale claims, thereby preserving the integrity of the legal system.

Purpose of the Doctrine of Laches:

- The doctrine ensures that an unreasonable delay in filing a suit cannot be excused. The petitioner must offer a reasonable explanation for the delay.

- Even with the delay, the petitioner may approach the court under Article 32 of the Constitution of India, 1950 (COI), but the judge retains discretion in granting relief.

- It aids the defendant’s case, particularly when evidence is lost, or witnesses are unavailable, by shifting the burden of proof onto the petitioner.

- The doctrine aims to prevent applicants from unnecessarily delaying the filing of their claims.

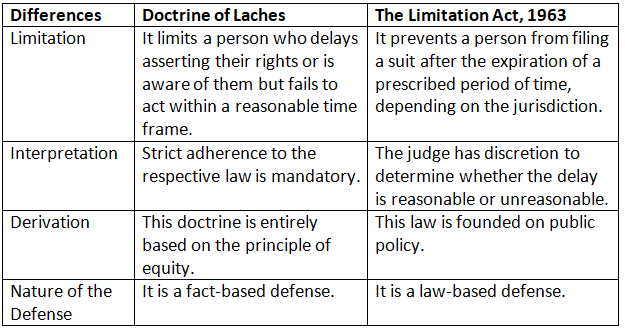

What are the Differences between Doctrine of Leaches and Statute of Limitation?

What is Article 226 of the COI?

- Article 226 is enshrined under Part V of the Constitution, granting the High Court the authority to issue writs.

- Article 226(1) of the Constitution of India (COI) provides that every High Court shall have the power to issue orders or writs, including habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and certiorari, to any person or government for the enforcement of fundamental rights and other purposes.

- Article 226(2) states that the High Court has the power to issue writs or orders to any person, government, or authority:

- Located within its jurisdiction, or

- Outside its local jurisdiction, if the cause of action arises wholly or partly within its territorial jurisdiction.

- Article 226(3) specifies that if an interim order is passed by the High Court in the form of an injunction, stay, or other means against a party, that party may apply to the court for the vacation of the order, and such an application must be disposed of by the court within two weeks.

- Article 226(4) clarifies that the power granted under this article to a High Court does not diminish the authority conferred upon the Supreme Court by Clause (2) of Article 32.

- This article can be issued against any person or authority, including the government.

- It is a constitutional right and not a fundamental right, and cannot be suspended even during an emergency.

- Article 226 is mandatory when it comes to the enforcement of fundamental rights, but discretionary when issued for "any other purpose."

- It enforces not only fundamental rights but also other legal rights.

|

63 videos|175 docs|37 tests

|

FAQs on Legal Current Affairs for CLAT (August 2024) - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What is the significance of the dissent in the SC/ST sub-classification case? |  |

| 2. How does the citizenship of a child relate to the SC/ST sub-classification debate? |  |

| 3. In what ways is the freedom of speech and expression not absolute in the context of legal affairs? |  |

| 4. What is the process for filing Special Leave Petitions (SLPs) in the Supreme Court of India? |  |

| 5. What is the principle of denying relief in legal contexts, particularly related to SC/ST issues? |  |