Legal Current Affairs for CLAT (July 2024) | Legal Reasoning for CLAT PDF Download

Article 14

Why in News?

Recently, the Supreme Court resolved a 22-year-old dispute regarding pay scales for education department officials in Uttar Pradesh in the case State of Uttar Pradesh and Anr. v. Virendra Bahadur Katheria and Ors.. The Court exercised its extraordinary powers under Article 142 of the Constitution to settle the issue, addressing the interests of both retired officials and the state government. This judgment clarified the application of the doctrine of merger and res judicata in cases involving multiple rounds of litigation between the High Court and the Supreme Court.

Background of State of Uttar Pradesh and Anr. v. Virendra Bahadur Katheria and Ors.

- 2001: The pay scales for Headmasters of Junior High Schools were revised upwards, creating a disparity with Sub-Deputy Inspectors of Schools (SDI)/Assistant Basic Shiksha Adhikaris (ABSA) and Deputy Basic Shiksha Adhikaris (DBSA), who previously had higher pay scales.

- 2002: Affected officials filed a writ petition seeking higher pay scales.

- The High Court ruled in their favor, directing that higher pay scales be granted from 2001.

- The state appealed to the Supreme Court.

- During the Appeal:

- The state proposed a policy to rectify the anomaly by merging posts and granting higher pay scales from 2006 (notionally) and 2008 (actually).

- 2010: The Supreme Court approved this proposal and dismissed the state’s appeal, directing implementation.

- 2011: The state issued orders implementing the Supreme Court's directive.

- Post-Implementation Issues:

- Some affected officials filed fresh writ petitions seeking benefits from 2001 instead of 2008.

- 2018: A Single Judge ruled in their favor.

- The state filed a delayed appeal against this 2018 order.

- 2023: The High Court dismissed the state’s appeal due to the delay.

- Supreme Court Appeal: The state has now approached the Supreme Court against the dismissal of its delayed appeal.

Court's Observations

- Pay Parity as a Right: The court observed that pay parity cannot be claimed as an indefeasible right unless the competent authority explicitly equates two posts, even if there are differences in nomenclature or qualifications.

- Incidental Pay Scales: Merely granting identical pay scales to different posts without express equation does not amount to an anomaly that infringes Article 16 of the Constitution.

- Policy Decision on Pay Scales: Prescription of pay scales is a policy decision based on expert recommendations, and the State must ensure that promotional posts are not remunerated less than feeder cadres.

- Cadre Management: Decisions regarding the creation, merger, de-merger, or amalgamation of cadres for administrative efficiency are within the State's prerogative. Judicial intervention is appropriate only in cases of blatant violations of Articles 14 and 16.

- Article 142 Invocation: The court invoked Article 142 to ensure complete justice, considering the lengthy litigation and its impact on retired respondents.

- Government Order Upheld: The court upheld the 2011 Government Order granting restructured benefits, applying it notionally from January 1, 2006, and with effect from December 1, 2008.

- Non-Recovery of Excess Payments: The court directed that excess payments made to respondents should not be recovered, adhering to the principle established in State of Punjab v. Rafique Masih.

- Finality in Pay Parity Disputes: The judgment stressed the importance of resolving prolonged pay parity disputes promptly to avoid them becoming infructuous due to delays.

Article 14 of the Constitution of India

- Equality Before the Law: Article 14 affirms the fundamental right to "equality before the law" and "equal protection of the law" for all persons.

- Origins of Expressions: The expression "equality before the law" originates from English law, while "equal protection of the law" is derived from the American Constitution.

- Preamble's Core Principle: Equality is a cardinal principle enshrined in the Preamble of the Constitution of India as its primary objective.

- Fair Treatment: It mandates treating all human beings with fairness and impartiality.

- Non-Discrimination: It establishes a system of non-discrimination based on grounds mentioned in Article 15 of the Constitution of India.

Exceptions to Article 14

The principle of equality under Article 14 is not absolute and allows for exceptions in specific circumstances:

- Foreign Diplomats: Article 14 does not apply to foreign diplomats due to their special privileges under international law.

- Special Circumstances: Laws applicable to a single individual or entity may be constitutionally valid if justified by special circumstances.

- Presumption of Constitutionality: Enacted laws are presumed constitutional, and the burden of proving unconstitutionality lies on the challenger.

- Rebuttal of Presumption: This presumption can be rebutted if a law arbitrarily singles out an individual or class without rational differentiation.

- Legislative Understanding: Courts presume the legislature understands societal needs and solves problems through experience-based laws.

- Factors for Constitutionality: Courts may rely on common knowledge, reports, historical context, and conceivable factual scenarios to uphold constitutionality.

- Varying Degrees of Harm: Legislatures can address varying levels of harm, focusing on the most pressing issues.

- Good Faith Presumption: While legislative good faith is presumed, courts do not assume unknown justifications automatically validate discriminatory laws.

- Basis of Classification: Classification can consider factors like geography, occupation, or legislative objectives.

- Similarity of Treatment: Perfect equality isn’t required; similarity of treatment suffices.

- Scope of Article 14: Its equal protection clause applies to both substantive and procedural laws.

Reasonable Classification under Article 14

Article 14 prohibits class legislation but allows reasonable classification of persons, objects, or transactions for legislative purposes, provided it meets certain criteria:

- Constitutionality Test: Laws are constitutional if classification satisfies specific legal tests.

- Common Sense over Legal Subtlety: Reasonableness is judged more by common sense than technical legal nuances.

- Non-Arbitrary Classification: Classification must not be arbitrary but should rest on substantial distinctions relevant to the law’s objectives.

- Intelligible Differentia: Must distinguish the grouped individuals or objects from those left out.

- Rational Nexus: The differentia must have a rational relation to the object sought to be achieved by the Act.

- State of West Bengal v. Anwar Ali Sarkar (1952): Two conditions for reasonable classification:

- The classification must be based on an intelligible differentia.

- The differentia must have a rational connection to the objective of the law.

- Distinct Elements: The differentia and the objective of the Act are distinct; the connection between them is crucial for validity.

Doctrine of Arbitrariness

Fairness and arbitrariness cannot coexist. This doctrine evolved to eliminate arbitrariness from reasonable classifications:

- Foundation: Introduced in E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu (1973), equality was defined as a dynamic concept, incompatible with arbitrariness.

- Key Cases: The doctrine was applied in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) and R.D. Shetty v. International Airport Authority (1979), where courts held that arbitrariness results in deprivation of equality.

- Exclusion of Arbitrariness: Courts excluded decisions containing arbitrariness from the ambit of reasonable classification.

Admission of Genuineness of Document not Violative of Article 20 (3) of the Constitution of India

Why in News?

Recently, the Supreme Court in the case of Ashok Daga v. Directorate of Enforcement held that calling an accused to admit or deny the genuineness of a document does not violate their right against self-incrimination

Background of the Ashok Daga v. Directorate of Enforcement Case

- The primary issue raised in the case was whether requiring a person to admit or deny the genuineness of a document under Section 294 of the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) violates Article 20(3) of the Constitution of India (COI).

- A Special Leave Petition was filed before the Supreme Court to address this issue.

Court’s Observations

- The court highlighted that Article 20(3) of the Constitution provides the right against self-incrimination, ensuring that no person can be compelled to be a witness against themselves.

- The Supreme Court observed that the purpose of Section 294 of CrPC is to expedite trial proceedings by focusing on relevant evidence and setting aside irrelevant documents.

- The court noted that a person’s failure to appear for admitting or denying the genuineness of a document could result in an adverse decision against them.

- It was further held that requiring an accused to admit or deny the genuineness of a document to facilitate a speedy trial does not violate Article 20(3) of the Constitution.

Section 330 of BNSS, 2023

About:

- Section 330 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023 specifies the documents for which formal proof is not required.

- This provision was earlier covered under Section 294 of the CrPC.

- Two new provisos have been added under Section 330 of BNSS.

Section 330:

- Clause (1):

- States that when any document is filed before any Court by the prosecution or the accused, the particulars of such document shall be included in a list.

- The prosecution, the accused, or their advocates, if any, shall be required to admit or deny the genuineness of each such document soon after supply of such documents and in no case later than thirty days after such supply.

- Provided: The Court may, at its discretion, relax this time limit with reasons recorded in writing.

- Provided further: No expert shall be required to appear before the Court unless their report is disputed by either party to the trial.

Clause (2):

- The list of documents shall follow a format prescribed by the State Government.

Clause (3):

- If the genuineness of a document is not disputed, it may be read as evidence in any inquiry, trial, or proceeding under this Code without proving the signature of the person to whom it purports to belong.

- Provided: The Court may, at its discretion, require such signature to be proved.

Right Against Self-Incrimination

About:

- Based on the legal maxim nemo teneteur prodere accusare seipsum, meaning a person cannot be compelled to make self-incriminating statements.

- This principle ensures that a person cannot be forced to provide information or testify against themselves in a criminal case.

- In jurisdictions such as the US and India, the right against self-incrimination is a constitutional or legal safeguard.

Article 20 of the Constitution of India

Protection in respect of conviction for offences:

- Clause (1):

- No person shall be convicted of an offence except for the violation of a law in force at the time of committing the act charged as an offence.

- No person shall be subjected to a penalty greater than what could have been imposed under the law in force at the time of the commission of the offence.

- Clause (2):

- No person shall be prosecuted and punished for the same offence more than once.

- Clause (3):

- No accused person shall be compelled to be a witness against themselves.

What are Landmark Judgments on Self-Incrimination?

- Nandini Satpathy v. P.L. Dani (1978): This case underscored the significance of the right against self-incrimination. The Court emphasized that this right is applicable to both accused individuals and witnesses, affirming that no one can be compelled to incriminate themselves under any circumstances.

- Ritesh Sinha v. State of Uttar Pradesh (2019):The Supreme Court, in this case, expanded the scope of handwriting samples to include voice samples, clarifying that such a directive would not violate the right against self-incrimination.

- Additionally, it was declared that a Magistrate has the authority to compel an individual to provide voice samples during an investigation.

Right to Speedy Trial

Why in News?

- A bench of Justice Farjand Ali of the Rajasthan High Court held that the right to a speedy trial is guaranteed by the Constitution.

- This ruling was made in the case of Kailash Chand v. State of Rajasthan.

Background of Kailash Chand v. State of Rajasthan Case

- An application was filed under Section 439 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 (CrPC).

- The accused argued that no case was made out for the alleged offences and that he should be granted bail.

- The petitioner had been in custody for a period of three years.

Court’s Observations

- The High Court noted that more than three years had passed, and only 12 out of 30 prosecution witnesses had been examined.

- The trial was progressing at a snail’s pace, and it was likely to take even longer to complete.

- The Court held that the accused could not be kept in custody in a pending trial due to delays in producing evidence against him.

- It emphasized that the right to a speedy trial is a constitutional guarantee and cannot be denied based on the seriousness or heinousness of the crime.

- Consequently, the Court granted bail under Section 439 of the CrPC.

Origin of the Right to Speedy Trial

- The right to a speedy trial originates from a provision in the Magna Carta.

- A fair trial inherently includes a speedy trial. No procedure can be considered reasonable, fair, and just unless it ensures a timely determination of guilt.

- Quick justice is an essential aspect (sine qua non) of Article 21 of the Constitution of India, 1950 (COI).

What is the Right to Speedy Trial?

Hussainara Khatoon & Ors v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar, Patna (1979)

- A writ of habeas corpus was filed on behalf of individuals languishing in Bihar jails while awaiting trial.

- Many of these undertrials had already served the maximum sentence possible for the offences they were accused of.

- The Supreme Court expanded the interpretation of Article 21 of the Constitution and held that the right to a speedy trial is a component of the right to life and personal liberty.

- Hon’ble Justice P.N. Bhagwati expressed anguish over the large number of undertrials in Indian jails.

Santosh De v. Archna Guha (1994)

- The Court noted an 8-year delay in conducting the case due to the prosecution.

- For the last 14 years, there had been no progress in the trial.

- The Supreme Court held that such delays by the prosecution defeat the accused's right to a speedy trial.

- The Court declined to interfere with the order quashing the proceedings, emphasizing that delays violate the accused's constitutional rights.

Kartar Singh v. State of Punjab (1994)

- The Court observed that the right to a speedy trial under Article 21 begins from the moment of arrest and continues through investigation, inquiry, trial, appeal, and revision stages.

- The constitutional guarantee of a speedy trial is reflected in Section 309 of the CrPC.

Is Right to Speedy Trial a Ground for Bail?

Ashim @ Asim Kumar Haranath Bhattacharya v. National Investigation Agency (2021)

- The accused pleaded for post-arrest bail.

- The Court, considering the fundamental right of undertrial prisoners to a timely trial, granted post-arrest bail to the appellant, noting the extended duration of imprisonment without trial.

Union of India v. K.A. Najeeb (2021)

- The Court emphasized balancing the prosecution's right to present evidence and establish charges with the accused’s rights guaranteed under Part III of the Constitution.

- It was held that, given the significant time spent in jail by the accused and the likelihood of further trial delays, the accused should be released on bail.

Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation (2022)

- The Court acknowledged the high number of undertrial prisoners languishing in jail and noted that arrest is a severe measure to be used sparingly.

- Unreasonable delay in the trial was recognized as a valid ground for granting bail to the accused.

Lichhman Ram @ Laxman Ram v. State (2023)

The Rajasthan High Court addressed factors to consider when adjudicating bail applications in the context of the right to a speedy trial:

- Delays caused by the accused as a defense tactic must be distinguished. The origin of delays must be assessed, as not all delays necessarily prejudice the accused.

- The interpretation of the right to a speedy trial must account for the nature of the offense, severity of punishment, number of accused and witnesses, systemic delays, and prevailing local conditions.

- If there is compelling evidence that the accused may flee justice or would be difficult to reapprehend, bail should not be granted.

- If credible material suggests that releasing the accused may disrupt societal harmony, intimidate prosecution witnesses, or otherwise hinder evidence collection, bail must be granted with extreme caution.

Right to Speedy Trial in the International Context

United States of America

- The Sixth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution ensures that in all criminal prosecutions, the accused has the right to a speedy and public trial.

- The Speedy Trial Act of 1974 establishes specific time limits for key events such as information, indictment, and trial proceedings.

- In Strunk v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the denial of an accused’s right to a speedy trial mandates either dismissal of the indictment or reversal of the conviction.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

- Article 8 states: “Everyone has the right to an effective remedy by the competent national tribunals for acts violating the fundamental rights granted to him by the constitution or by law.”

Right to Freely Profess, Practice & Propagate Religion

Why in News?

The Allahabad High Court recently observed the distinction between individual freedom of religious expression and the collective act of proselytization in Shriniwas Rav Nayak v. State of U.P. The court emphasized that while individuals have the constitutional right to freely choose and practice their religion, they cannot convert others to their faith.

Background of Shriniwas Rav Nayak v. State of U.P.

- The applicant is involved in a case under Sections 3/5(1) of the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act, 2021.

- The incident occurred on 15th February 2024 at the house of co-accused Vishwanath in Nichlaul, District Maharajganj.

- The informant was invited to Vishwanath’s house, where he found many villagers, mostly from the Scheduled Castes community.

- Present at the house were co-accused Vishwanath, his brother Brijlal, the applicant, and one Ravindra.

- The informant was allegedly asked to leave Hinduism and accept Christianity, with promises of ending pain and progress in life.

- Some villagers reportedly accepted Christianity and started praying.

- The informant escaped and informed the police.

- The applicant claims to be a domestic help of one of the co-accused and a resident of Andhra Pradesh.

- The applicant’s counsel argued that the FIR doesn’t identify any “religion converter” as defined by the Act.

- The prosecution contended that mass conversion was taking place, and the applicant was actively participating.

- Police recorded statements from independent witnesses confirming the conversion event.

- The court found prima facie evidence of unlawful religious conversion under the Act.

- The bail application was rejected, citing that Section 3 of the Act prohibits religious conversion, punishable under Section 5.

Court’s Observations

- The Court noted that the Uttar Pradesh Prohibition of Unlawful Conversion of Religion Act, 2021 was enacted to prohibit unlawful conversions through misrepresentation, force, undue influence, coercion, allurement, fraudulent means, or marriage.

- The Court emphasized that the Constitution guarantees religious freedom, but the individual right to freedom of conscience and religion does not translate into a collective right to proselytize.

- Section 3 of the Act explicitly prohibits conversion through misrepresentation, force, fraud, undue influence, coercion, and allurement.

- The Court clarified that Article 25 of the Constitution of India, 1950 (COI), while providing for freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion, does not permit citizens to convert others to their religion.

- The Act was deemed consistent with constitutional provisions.

Article 25 of the Constitution of India (COI)

Legal Provisions:

- Article 25 guarantees freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion.

- It is subject to public order, morality, and health, as well as other provisions in the Constitution.

- It does not prevent the State from making laws:

- Regulating or restricting economic, financial, political, or other secular activities associated with religious practices.

- Providing for social welfare and reform, including opening Hindu religious institutions of a public character to all classes and sections of Hindus.

Key Features of Article 25:

- Guarantees freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion.

- This right is subject to public order, morality, and health.

- Permits the State to regulate economic, financial, political, or secular activities related to religious practices.

- Allows the State to make laws for social welfare and reform, including opening Hindu religious institutions to all classes and sections of Hindus.

Additional Explanations:

- Explanation I: Wearing and carrying of kirpans is deemed included in the profession of the Sikh religion.

- Explanation II: The reference to Hindus includes persons professing Sikh, Jaina, or Buddhist religions, and Hindu religious institutions are construed accordingly.

Judicial Clarifications:

- While Article 25 guarantees the right to propagate religion, it does not include the right to convert another person to one’s religion, as clarified by the Supreme Court in several judgments.

- The right is available to all persons, including both citizens and non-citizens.

Article 25: Freedom of Conscience and Free Profession, Practice, and Propagation of Religion

Fundamental Right Enshrined:

- Article 25 guarantees that all individuals have the equal right to freedom of conscience and the freedom to profess, practice, and propagate their religion.

Implications of Article 25:

- Freedom of Conscience: This refers to an individual's inner freedom to shape their relationship with God or any divine entity or creature in whatever manner they wish.

- Right to Profess: This entails the right to openly and freely declare one’s religious beliefs and faith.

- Right to Practice: This involves the freedom to engage in religious worship, rituals, ceremonies, and public displays of beliefs and ideas.

- Right to Propagate: This includes the right to spread or communicate one’s religious beliefs to others or to explain the tenets of their religion.

Scope of Article 25:

- Article 25 encompasses both religious doctrines (beliefs) and religious practices (rituals).

- Additionally, the rights provided under this article are available to all persons, including both citizens and non-citizens.

Restrictions:

- These rights are subject to reasonable restrictions based on public order, morality, health, and other provisions relating to fundamental rights.

- The State has the authority to regulate or restrict any economic, financial, political, or other secular activities related to religious practices.

What are the Major Judicial Pronouncements on Freedom of Religion?

Bijoe Emmanuel and Others v. State of Kerala (1986)

- In this case, three children belonging to the Jehovah’s Witnesses sect were suspended from school for refusing to sing the national anthem, claiming it went against their religious beliefs.

- The Court ruled that the expulsion violated their fundamental right to freedom of religion.

Acharya Jagdishwar Anand v. Commissioner of Police, Calcutta (1983)

- The Court held that Ananda Marga is a religious denomination, not a separate religion, and that the performance of Tandava on public streets is not an essential religious practice of Ananda Marga.

M. Ismail Faruqui v. Union of India (1994)

- The Supreme Court ruled that a mosque is not an essential practice of Islam, and that Muslims can offer namaz (prayer) anywhere, even in open spaces.

Ratilal Panachand Gandhi v. State of Bombay (1954)

- The Supreme Court stated that religious practices are as integral to religion as religious faith or doctrines.

- However, it also clarified that this protection applies only to practices that are essential and integral to the religion.

Commissioner, Hindu Religious Endowments, Madras v. Sri Lakshmindra Thirtha Swamiar of Sri Shirur Mutt (1954)

- This case introduced the "essential religious practices" test.

- The Court ruled that what constitutes an essential part of a religion must be determined based on the doctrines of that religion itself.

Sardar Syedna Taher Saifuddin Saheb v. State of Bombay (1962)

- The Court held that the head of the Dawoodi Bohra community had the right to excommunicate its members, as this was an essential religious practice.

Stainislaus v. State of Madhya Pradesh (1977)

- The Court ruled that the right to propagate religion under Article 25 does not include the right to convert others to one’s own religion.

- This judgment upheld the validity of anti-conversion laws.

Indian Young Lawyers Association v. State of Kerala (2018) - Sabarimala Temple case

- The Court ruled that the practice of prohibiting women of menstruating age from entering the Sabarimala temple was not an essential religious practice.

- It emphasized that constitutional morality must take precedence over religious beliefs and practices.

Right to Profession, Dignity & Equality

Why in the News?

The Supreme Court, in the case of Gaurav Kumar v. Union of India, ruled that the high enrollment fees imposed by State Bar Councils (SBCs) are unconstitutional. The Court found that these fees infringe upon aspiring lawyers' right to practice and violate the principle of equality. The Court also set a cap on these fees: Rs. 750 for general category advocates and Rs. 125 for SC/ST advocates, ensuring that the fees do not discriminate against marginalized groups.

Background of the Gaurav Kumar v. Union of India Case

- The Advocates Act, 1961 (the Act) was passed to amend and consolidate the laws related to legal practitioners and to establish a common Bar for India.

- The Act created State Bar Councils (SBCs) and the Bar Council of India (BCI).

- SBCs are responsible for admitting advocates, maintaining rolls, handling misconduct cases, and protecting advocates' rights.

- BCI’s role includes setting standards for professional conduct, overseeing SBCs, and regulating legal education.

- To be admitted as an advocate, individuals must meet specific qualifications outlined in Section 24 of the Act.

- Section 24(1)(f) of the Act specifies the enrollment fees payable to SBCs and BCI.

- However, SBCs charge additional fees beyond the statutory enrollment fees, with amounts ranging from Rs. 15,000 to Rs. 42,000 in total.

- A petition was filed under Article 32 of the Constitution of India, 1950, challenging these additional fees as violating Section 24(1)(f) of the Advocates Act.

- The petition argued that the fee structure was inconsistent with Article 19(1)(g), which protects the right to practice a profession, and infringed upon the rights to dignity (Article 21) and equality (Article 14).

- The Supreme Court recognized the significance of the case and issued a notice. Similar petitions from various High Courts were transferred to the Supreme Court.

- The core issues were whether the enrollment fees charged by SBCs violated Section 24(1)(f) of the Act and whether additional fees could be imposed as a condition for enrollment.

Court's Observations

- The Court held that the exorbitant enrollment fees charged by SBCs violate an aspiring lawyer’s right to choose their profession and their dignity, as protected under Articles 19(1)(g) and 21 of the Constitution.

- The Court ruled that enrollment fees cannot exceed Rs. 750 for general category advocates and Rs. 125 for SC/ST advocates.

- The Court emphasized the connection between the right to practice a profession under Article 19(1)(g) and its impact on the right to dignity (Article 21) and equality (Article 14).

- The Court found that high enrollment fees create significant barriers to entering the legal profession, especially for individuals from marginalized and economically disadvantaged backgrounds, thus violating the principle of substantive equality.

- The Court concluded that these excessive fees are arbitrary under Article 14 and create financial barriers for lawyers from marginalized communities.

- The Court interpreted the Advocates Act as aiming to promote inclusivity in the legal profession, which cannot be undermined by arbitrary fee structures.

- The Court ruled that SBCs’ practice of charging excessive fees is manifestly arbitrary and does not align with the provisions of Section 24(1)(f) of the Advocates Act.

- The right to practice law is both statutory under Section 30 of the Advocates Act and fundamentally protected by Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution, subject to reasonable restrictions under Article 19(6).

- The Court found the current fee structure set by SBCs to be unreasonable and in violation of Article 19(1)(g).

- The Court held that SBCs cannot charge enrollment fees beyond what is stipulated in Section 24(1)(f) of the Advocates Act.

- The Court ruled that SBCs and BCI cannot demand any additional fees, other than the prescribed enrollment fee and stamp duty, as a pre-condition for enrollment.

- The Court's decision will have a prospective effect, meaning SBCs are not required to refund any excess fees collected before the date of the judgment.

Relevant Legal Provisions Involved

Advocate Act, 1961:

- Section 24 of the Advocate Act, 1961 deals with persons who may be admitted as advocates on a State roll.

- Section 24(1)(f) prescribes that a person must have paid the enrolment fee, stamp duty (if applicable under the Indian Stamp Act, 1899), and an enrolment fee of six hundred rupees to the State Bar Council and one hundred and fifty rupees to the Bar Council of India via a bank draft in favor of the respective council.

Constitutional Law:

- Article 14 deals with equality before the law:

- Article 14 ensures that the State shall not deny any person equality before the law or equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.

- Article 19 protects certain rights regarding freedom of speech, etc.:

- Article 19(1)(g) states that all citizens shall have the right to practice any profession or carry on any occupation, trade, or business.

- Article 21 protects life and personal liberty:

- Article 21 ensures that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except in accordance with the procedure established by law.

- Principles for Levying Fees by Authorities:

- The power to impose restrictions under Article 19(1)(g) is not absolute and must be exercised reasonably.

- Fees or licenses must be valid and levied based on the authority of law.

- Delegated legislation, if contrary to or beyond the scope of the parent legislation's policy, places an unreasonable restriction, thereby violating Article 19(1)(g).

- Right to Profession, Dignity, and Equality:

- Right to Profession: Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution of India grants all citizens the right to practice any profession or carry on any occupation, trade, or business, subject to reasonable restrictions under Article 19(6).

- Right to Dignity: Article 21 of the Constitution ensures that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except according to the procedure established by law. The Supreme Court has interpreted this as including the right to live with human dignity.

- Right to Equality: Article 14 guarantees that the State shall not deny any person equality before the law or the equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.

These fundamental rights are often interpreted together by courts to ensure substantive equality and the protection of individual dignity in professional contexts.

Major Case Laws Referred to in this Case

Ravinder Kumar Dhariwal v. Union of India (2023):

- The court held that ensuring equality in outcomes through various forms of affirmative action contributes to the larger aim of substantive equality.

Khoday Distilleries Ltd v. State of Karnataka (1996):

- Established principles for challenging delegated legislation: a) The test of arbitrary action for executive actions does not necessarily apply to delegated legislation. b) Delegated legislation can only be struck down if it is manifestly arbitrary. c) Manifest arbitrariness occurs when delegated legislation does not conform to the statute. d) Delegated legislation is also manifestly arbitrary if it offends Article 14.

Mohammad Yasin v. Town Area Committee (1952):

- Focused on the validity of bylaws and the scope of authority in imposing license fees.

- Justice SR Das held that the license fee:

- Took away the business owner's property (money).

- Restricted their right to do business.

- The license fee was found to violate Article 19(1)(g) and was not considered a 'reasonable restriction'.

R M Seshadri v. District Magistrate (1954):

- A Constitution Bench case dealing with conditions imposed on movie theater licensees.

- The court found the conditions vague, overly broad, and lacking clear instructions.

- These conditions were held to violate Article 19(1)(g) as they severely affected the cinema business.

Renewal of Passport

Why in News?

A bench of Justice A. Badharudeen ruled that imposing onerous conditions for the re-issuance or renewal of a passport is unnecessary. This judgment was delivered in the case of Jesmon Joy Karippery v. State of Kerala.

Background of the Jesmon Joy Karippery v. State of Kerala Case

The petitioner in this case approached the High Court challenging the conditions imposed by the Magistrate while granting permission to renew his passport.

The conditions imposed by the Magistrate for renewing the passport were as follows:

- The petitioner was required to execute a bond of Rs. 30,000.

- The petitioner had to furnish a cash security of Rs. 3,000.

- The petitioner was instructed to produce a photocopy of the passport, duly attested by himself and one witness, within one week after receiving the passport.

- The petitioner was directed to ensure that the trial of the case was not delayed or prolonged due to his absence.

- The petitioner was required to appear before the court whenever required.

- The petitioner was to file an affidavit confirming that he would be duly represented by counsel holding vakalath and that he would not dispute his identity during the trial.

Court’s Observations

- The Court held that the conditions imposed by the Magistrate were onerous and unnecessary.

- The Court observed that when an accused person seeks permission only to renew their passport, and not to travel abroad, the court need not impose such stringent conditions.

- The Court further stated that only necessary conditions should be imposed when an accused seeks permission to travel abroad.

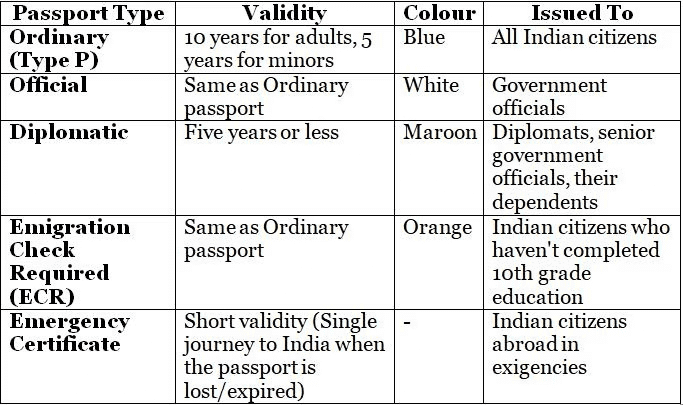

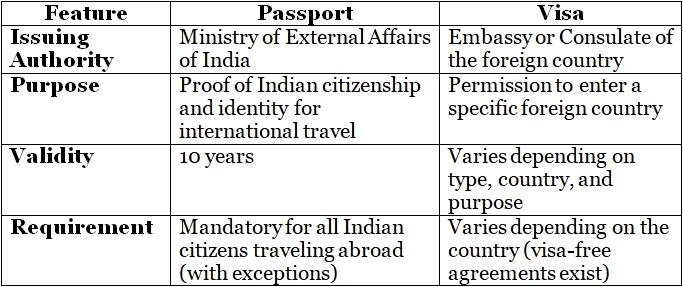

Relevant Legal Provisions Related to Passport

- About: A passport is an official travel document issued by the government that certifies a person's identity and nationality for international travel.

The Passports Act, 1967:

- The Passports Act is a law enacted by the Parliament of India to regulate the issuance of passports and travel documents, and to control the departure of Indian citizens and others from India, along with other related matters.

- Section 6 of this Act outlines the grounds for refusal of passports.

Case Laws Regarding Renewal of Passport During Pendency of Criminal Proceedings

Vangala Kasturi Rangacharyulu v. Central Bureau of Investigation (2020)

- The Supreme Court held that refusal of a passport can only occur if an applicant is convicted for an offence involving moral turpitude and sentenced to imprisonment for not less than two years during the five years immediately preceding the date of application (Section 6(2)(e) of the Passports Act, 1967).

- Renewal of a passport cannot be refused solely because a criminal proceeding is pending against the accused.

Ganni Bhaskara Rao v. Union of India and Another (2023)

- The Andhra Pradesh High Court observed that every person is presumed innocent until proven guilty.

- Accordingly, the pendency of a case is not a valid ground to refuse, renew, or demand the surrender of a passport.

Right to Travel Abroad

The right to travel abroad is not explicitly stated in the Constitution of India. However, it has been interpreted as part of the fundamental right to life and personal liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution.

- Satwant Singh Sawhney v. D. Ramarathnam, Assistant Passport Officer, Government of India, New Delhi (1967): The Supreme Court held that the right to travel abroad is a fundamental right under Article 21. It also stated that the government cannot refuse to issue or impound a passport without adhering to a valid procedure established by law.

Relevant Provisions in the Constitution

- Article 21:

- No person shall be deprived of their life or personal liberty except according to a procedure established by law.

- Article 19(1)(d):

- This guarantees freedom of movement, which has been interpreted to include the right to travel within the country.

- Article 19(1)(a):

- This guarantees freedom of speech and expression, which can be extended to encompass the right to travel abroad for educational, cultural, or professional purposes.

|

63 videos|175 docs|37 tests

|

FAQs on Legal Current Affairs for CLAT (July 2024) - Legal Reasoning for CLAT

| 1. What is the significance of Article 14 in the context of genuine document admission? |  |

| 2. How does Article 20(3) relate to the admission of documents in legal proceedings? |  |

| 3. What are the implications of the right to a speedy trial in relation to document admission? |  |

| 4. How does the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion intersect with legal document admissions? |  |

| 5. What is the process for the renewal of a passport in relation to the legal rights guaranteed by the Constitution? |  |