Megalithic Culture | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Understanding Megaliths

Definition of Megalith

- The word "megalith" comes from the Greek words "megas," meaning great, and "lithos," meaning stone. Therefore, megaliths are large stone monuments.

- However, not all large stone structures qualify as megaliths. The term is specifically used for certain types of monuments or structures made of big stones that have a connection to burial, commemoration, or rituals, excluding hero stones or memorial stones.

- Megaliths typically refer to large stone burials found in graveyards away from living areas.

Chronology of Megalithic Culture

- Archaeological evidence, particularly from the Brahmagiri excavation, suggests that the megaliths in South India date back to between the 3rd century B.C. and the 1st century A.D. This dating is based on the presence of a specific type of pottery called Black and Red Ware (BRW), found in all types of megaliths in the region.

- Despite this, the Megalithic culture in South India spans a much longer period. The challenge in determining the chronological range of these cultures arises from the limited radiocarbon dating available from megalithic sites.

- The habitation site at Hallur has been dated to around 1000 B.C., which corresponds with graves found at Tadakanahalli, located 4 kilometers away.

- Radiocarbon dates from sites like Naikund and Takalghat place the Vidarbha megaliths around 600 B.C.

- In Tamil Nadu, the site of Paiyampalli has been dated to around the 4th century B.C.

- Explorations and excavations in North Karnataka have pushed the date of megaliths back to as early as 1200 B.C.

- The megalithic culture overlaps with the later phases of the neolithic-chalcolithic culture, being found alongside neolithic-chalcolithic wares at one end and rouletted ware from the first millennium A.D. at the other end.

- Based on these findings, the time frame for megalithic cultures in South India is estimated to be between 1000 B.C. and A.D. 100, with their peak popularity likely occurring between 600 B.C. and A.D. 100.

Origin and Spread of Megalithic Cultures

- The megalithic culture in India is believed to have been brought by Dravidian speakers who arrived in South India from West Asia by sea.

- In West Asia, typical megaliths were associated with bronze objects, and this culture ended during the last phase of the Bronze Age around 1500 B.C.

- In contrast, Indian megaliths belong to the Iron Age, generally dated from 1000 B.C. onwards.

- The development of iron technology and its integration into megalithic culture remain uncertain.

- The differences between northern and southern Indian megalithic cultures suggest that the culture entered the Indian subcontinent through two different routes:

- One group traveled by sea from the Gulf of Oman to the West coast of India.

- Another group came by land from Iran.

- The variety of burial practices grouped under the term "megaliths" resulted from the blending of different traditions over a long period.

- Megaliths have been found in various chronological contexts throughout India, including Punjab, the Indo-Gangetic basin, Rajasthan, northern Gujarat, and especially in regions south of Nagpur in Peninsular India. They also continue as a living tradition in parts of northeastern India and the Nilgiris.

- The main concentration of megalithic cultures was in the Deccan, particularly south of the Godavari River. However, large stone structures resembling megaliths have been reported from parts of North India, Central India, and Western India, including:

- Seraikala in Bihar

- Deodhoora in Almora district

- Khera near Fatehpur Sikri in Uttar Pradesh

- Nagpur

- Chanda and Bhandara districts in Madhya Pradesh

- Deosa near Jaipur in Rajasthan

- Similar structures have also been found near Karachi in Pakistan, near Leh in the Himalayas, and at Burzahom in Jammu and Kashmir.

- Despite their wide distribution, the prevalence of megaliths in southern India indicates that this was primarily a South Indian feature that thrived for at least a thousand years.

Types of Sepulchral Megaliths

Sepulchral megaliths, which are designed to store the remains of the deceased, exhibit a variety of burial practices:

- Primary Burials: In primary burials, the deceased is interred shortly after death, and the burial typically contains a complete skeleton along with additional items meant to accompany the deceased in the afterlife. In some instances, primary burials may take place within a terracotta sarcophagus, providing valuable information about the burial customs and the items included.

- Secondary Burials: Secondary burials are characterized by the placement of the deceased's remains, usually bones, in urns or pits. The location of the burial is often marked by stone circles, although other features like cairns and slab circles may also be present on the surface.

- Dimensions and Markers: These megaliths are typically of dimensions similar to that of a human or even smaller. The area of the burial is occasionally delineated with stone circles, adding to the distinctive features of these sepulchral structures.

Megalithic Culture: The Iron Age Culture of South India

- The megalithic culture in South India represents a well-established Iron Age society where people had fully realized the advantages of using iron. As a result, stone began to fall out of favor as the primary material for weapons and tools.

- The megalithic people discovered new uses for stones in their daily lives. Most of the information about the Iron Age in South India comes from excavations of megalithic burials. Iron objects have been found universally across megalithic sites, from Junapani near Nagpur in the Vidharba region of Central India to Adichanallur in Tamil Nadu in the far south.

- The introduction of iron brought about gradual changes in various aspects of life, except perhaps in house designs. However, the most notable change was in the method of disposing of the dead, which became a distinctive feature of South Indian regions. Instead of burying the dead within the house with a few pots, the dead were now buried in separate places, such as cemeteries or graveyards, away from the house.

- The remains of the dead were often collected after exposing the body for some time, and the bones were placed underground in specially prepared stone boxes called cists. These cists were elaborate structures that required planning and cooperation within the community, as well as skilled masons and craftsmen capable of creating stones of the required size. It is likely that these megaliths were planned and constructed before an individual’s death.

Classification of the Megaliths

Megalithic burials exhibit various methods for disposing of the dead. Additionally, there are megaliths that, while differing internally, share the same external features. The megaliths can be classified into different categories:

1. Rock Cut Caves:

- These caves are carved into soft laterite rock, predominantly found in the southern part of the West Coast.

- They are unique to this region and can be found in the Cochin and Malabar regions of Kerala.

- Types of rock cut burial caves in the Cochin region include:

- Caves with a central pillar.

- Caves without a central pillar.

- Caves with a deep opening.

- Multi-chambered caves.

- These caves are also present on the East Coast of South India, such as in Mamallapuram near Madras.

2. Hood Stones (Kudaikallu) and Cap Stones (Toppikkals):

- Hood stones, or Kudaikallu, are simpler forms associated with rock cut caves and are primarily found in Kerala.

- These consist of a dome-shaped dressed laterite block covering an underground circular pit cut into natural rock, often with a stairway.

- In some instances, a cap stone or toppikkal, a plano-convex slab resting on quadrilateral boulders, replaces the hood stone.

- Cap stones also cover underground burial pits containing funerary urns and other grave items.

- Unlike rock cut caves, there are no chambers apart from the open pit where the burial takes place.

- Toppikkal monuments are commonly found in the Cochin and Malabar regions, extending along the Western Ghats into the Coimbatore region and up to the Noyyal river valley in Tamil Nadu.

3. Menhirs, Alignments, and Avenues:

- Menhirs are vertically planted monolithic pillars, which can vary in height and may be dressed or undressed.

- These commemorative stone pillars are set up at or near burial sites.

- In ancient Tamil literature, menhirs are referred to as nadukal and are often called Pandukkal or Pandil.

- Menhirs can be found in large numbers in regions such as Kerala, Bellary, Raichur, and Gulbarga in Karnataka, while being less frequent in other parts of South India.

- Alignments consist of a series of standing stones, sometimes dressed, and are associated with menhirs.

- Avenues consist of two or more parallel rows of alignments, with many alignment sites also serving as examples of avenues.

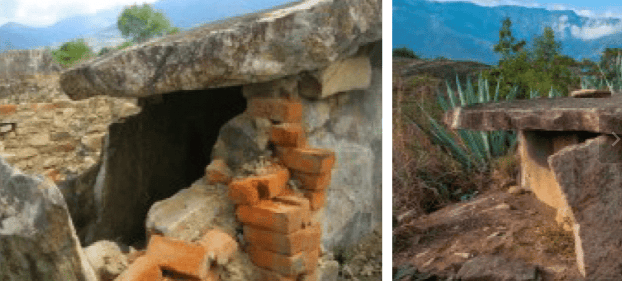

4. Dolmenoid Cists:

- These consist of square or rectangular box-like graves built of several upright stones (orthostats) supporting a capstone, often with a stone-paved floor.

- Orthostats and capstones may be undressed rough blocks or partly dressed stones.

- Dolmenoid cists are found in large numbers at sites like Sanur near Chingleput (Tamil Nadu) and many other locations in the region.

- Slab cists, built of dressed slabs, are the normal type of cists occurring throughout South India and parts of the north.

- In Tamil Nadu, there are various sub-types of dolmenoid cists, including those with multiple orthostats, U-shaped port-holes, and slab-circles.

5. Cairn Circles:

- Cairn circles are a popular type of megalithic monument found throughout South India in association with other types.

- They consist of a heap of stone rubble enclosed within a circle of boulders.

- Megalithic burial sites with cairn circles, dating from 1,000 BCE to 300 CE, have been discovered in regions like Veeranam.

- Pit burials under cairn circles involve deep pits of various shapes, where skeletal remains and grave furniture are placed, followed by earth filling and the cairn heap above.

- Such pit burials have been found in many sites across Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.

- Cairn circles with sarcophagus entombments are more widespread than pit burials, where skeletal remains and grave furniture are placed in a terracotta sarcophagus with a lid, surrounded by a cairn heap.

- These structures are found in various districts of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and the region around Nagpur.

- Urn burials under cairn circles involve pits filled with soil and capped with a heap of cairns, often surrounded by a circle of stones.

- These are predominant in regions of Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, and Nagpur.

Stone Circles

- Stone circles are the most frequently found megalithic monuments in India.

- They showcase various forms of megalithic structures, including Kudaikallu, Topikkal, different types of pit burials, menhirs, dolmenoid cists, and cairns.

- These stone circles are found from the southern tip of the peninsula up to the Nagpur region and in various parts of North India.

- In this category, only stone circles without significant cairn filling, containing burial pits with or without urns or sarcophagi, are considered.

Pit Burials

- Pit burials involve the interment of funerary deposits in large conical jars or urns, which are buried in specially dug underground pits.

- These pits are often excavated into hard natural soil or basal rock and are filled up after the burial.

- Unlike other burials, pit burials do not have any surface markers such as stone circles, cairns, hood stones, hat stones, or menhirs.

- These urn burials lack any megalithic features and cannot be classified as megalithic burial monuments.

- However, they share common traits with megalithic culture in South India, including the use of Black-and-red ware (BRW) and associated wares with iron objects.

- The grave goods found in these urn burials are similar to those in regular megalithic burials.

- Urn burials without megalithic appendages are predominantly found in Tamil Nadu, with sites like Adichanallur and Gopalasamiparambu.

- These burials are less common in Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh.

- In North India, similar urn burials are observed at Harappan and Later Chalcolithic sites, but their context differs from South Indian urn burials.

- For instance, an urn burial in Adichanallur involved skeletons covered with another urn in a twin-pot system, highlighting the care taken in burying the dead.

Barrows

- Barrows, or earthen mounds, are used to mark underground burials.

- They can be circular, oblong, or long in shape and may be surrounded by stone circles or ditches.

- Although not found in large numbers in India, barrows have been observed in the Hassan district of Karnataka.

[Intext Question]

Grave Goods in Megalithic Burials

The objects found in megalithic burials are crucial for understanding megalithic culture. These burials, dating back to the Later Palaeolithic period, show that the dead were intentionally buried for various reasons. The megalithic people, like their predecessors, built elaborate and labor-intensive tombs, filling them with essential objects. This practice stemmed from their belief in an afterlife, necessitating the provision of goods for the deceased's needs.

In South Indian megalithic graves, the typical grave goods included:

- a wide range of pottery;

- weapons and tools, primarily made of iron, but sometimes of stone or copper;

- ornaments such as necklaces, ear or nose ornaments, armlets, bracelets, and diadems made from materials like terracotta, semi-precious stones, gold, copper, shell, etc.;

- food items, evidenced by the presence of paddy husk, chaff, and other cereals;

- skeletal remains of animals, occasionally found whole in these graves.

Subsistence Pattern

Megalithic sites were initially thought to be settlements of nomadic pastoralists. However, evidence suggests that early iron age communities in far south India practiced a combination of agriculture, hunting, fishing, and animal husbandry. There is also evidence of well-developed craft traditions, indicating a sedentary lifestyle.

- Agriculture formed the backbone of the economy.

- The megalith builders introduced advanced agricultural methods, particularly tank-irrigation, revolutionizing the agricultural system in South India.

- They cultivated cereals, millets, and pulses, with rice being the staple food.

- Excavations have revealed charred grains of horse gram,green gram, and possibly ragi from sites like Paiyampalli.

- Paddy husks and grains have been found in graves across the region, indicating the significance of rice in their diet.

- Regional variations in crops were evident, with pestles and grinding stones found at some sites, indicating agricultural practices.

- The location of megalithic sites near irrigation tanks and the presence of agricultural implements suggest a strong agricultural foundation.

- Graves were strategically placed in unproductive areas, reserving fertile lands for agriculture.

- The presence of animal bones indicates the domestication and hunting of various species.

- Animals such as cattle,sheep,goat,dog,pig,horse,buffalo,fowl, and ass were domesticated.

- Cattle, including buffalo, were the most important domesticated animals, indicating a continuation of earlier neolithic traditions and a focus on cattle pastoralism.

- The remains of domesticated pig and fowl suggest small-scale pig rearing and poultry farming.

- Hunting supplemented the food supply, with equipment like arrowheads,spears, and javelins indicating hunting practices.

- Sling was likely used for hunting, as evidenced by the discovery of stone balls.

- Skeletal remains of various wild animals, such as wild boar,hyena,deer,peacock,leopard,tiger,bear,hog,fowl, and fish, indicate that these species were hunted and formed part of the diet.

- Paintings and figurines depict hunting scenes, providing insights into hunting practices.

- Fishing was evidenced by terracotta net sinkers and fish-hooks, along with skeletal remains of fish.

- The megalithic sites in South India show evidence of well-developed craft traditions.

- Industries and crafts such as smithery,carpentry,pottery making,lapidary,basketry, and stone cutting were significant economic activities.

- Various megalithic sites were known for the production of metals like iron,copper,gold, and silver.

- Smelting evidence includes crucibles,smelting-furnaces,clay tuyers, and iron ore pieces, indicating local smithery.

- Iron objects were prevalent, used for utensils,weapons,carpentry tools, and agricultural implements.

- Copper and bronze artefacts included utensils,bowls, and bangles, with some silver and gold ornaments found.

- Tools like axes,chisels,wedges,adzes,anvil,borers, and hammer stones were used for woodwork.

- Postholes indicate the presence of timber constructions for domestic buildings.

- Various ceramic fabrics like black-and-red ware,burnished black ware,red ware,micaceous red ware,grey ware, and russet-coated painted ware were produced.

- These wares included a range of shapes, indicating technical efficiency in pottery making.

- The evidence of pottery kilns supports the practice of this craft.

- Crafts like bead making,mat weaving,stone cutting, and terracotta making were practiced.

- Bead making industries at sites like Mahurjhari and Kodumanal indicate the production of beads from various materials.

- Mat weaving was practiced, as evidenced by mat impressions on jars.

- Rock art and paintings were also part of the craft repertoire.

In Summary: The megalithic people engaged in various craft industries alongside a specialized agro-pastoral economy. These diverse economic patterns were interconnected and contributed to their way of life.

Trade and Exchange Network

- Some megalithic sites were likely centers of craft production connected to exchange networks.

- The location of several large megalithic settlements along early historical trade routes suggests their involvement in trade.

- Excavations have uncovered non-local items among grave goods, indicating exchange activities during the megalithic period.

- Carnelian beads found at coastal sites, which were ancient points of exchange, further support this idea.

- The presence of bronze implies the arrival of copper and an alloy, possibly tin or arsenic, from distant sources.

- The circulation of non-local goods, as indicated by carnelian beads, suggests active exchange networks.

- Graeco-Roman writings and Tamil texts reveal that maritime exchange was a major source of goods during a later period.

- Archaeological remains like rouletted ware and amphorae found at sites like Arikamedu provide evidence of established inter-regional and intra-regional exchange of goods in South India by the 3rd century B.C.

- Regional variations in commodity production and the lack of local raw materials or finished goods led to long-distance transactions, driven by traders from the Gangetic region and overseas.

- The exchange network, initially in a nascent state during the early Iron Age, expanded over centuries due to internal dynamics and external factors, including demand for goods in various parts of the subcontinent and the Mediterranean.

- This network spanned land and sea, involving long-distance traders and unevenly developed communities on either side.

- Megalithic people, including hunter-gatherers and shifting cultivators of the Iron Age, actively participated in this exchange network.

Social Organization and Settlement Pattern

- Anthropology, rather than archaeology, provides evidence suggesting the possibility of production relations transcending clan ties and kinship during the remote periods of tribal descent groups.

- The material culture reflects diverse forms of subsistence, including hunting, gathering, shifting cultivation, and the production of a limited number of craft goods.

- Variations in burial features indicate that the Iron Age society of the megalithic people was not homogeneous.

- Some larger burial types suggest status differentiation and ranking among the buried individuals.

- Differences in burial types and contents imply disparities in the attributes of the buried individuals.

- Elaborate burials, such as multi-chambered rock-cut tombs, are limited in number and often contain rare artifacts made of bronze or gold.

- In contrast, many burials are simple urn burials with minimal artifacts.

- The variety, quality, and fineness of ceramic goods in large burials, including elaborate urn burials, suggest differences in social status.

- Individual treatment at death correlates with the individual’s status in life and the organization of their society.

- The megalithic people inhabited villages with sizable populations.

- Although they preferred urban life, they were slow to develop large cities compared to their contemporaries in the Gangetic Valley.

- The large population size is evident from the organized labor that transported and housed massive stone blocks for constructing cists, dolmens, and other megaliths.

- The population size is further supported by extensive burial grounds with numerous graves, some containing multiple individuals, occasionally numbering 20 or more.

- The houses of megalithic people likely consisted of huts with thatched or reed roofs, supported by wooden posts, as indicated by postholes found at excavated sites.

- At sites like Brahmagiri and Maski, postholes suggest timber construction for ordinary buildings.

- The increase in size and number of settlements during the megalithic period, along with the growing use of different metallic resources, was not an isolated development.

- The spread of plough cultivation significantly altered the structure and distribution of settlements.

- Analysis of site distribution patterns indicates a growing inclination towards intensive field methods.

- The concentration of sites in river valleys and basins, along with a preference for black soil and red sandy-loamy soil zones, supports this trend.

- The distribution of sites in areas with annual precipitation between 600-1500 mm further reinforces this conclusion.

- Village transhumance is evident from the location of most settlement sites along riverbanks and burial sites within 10-20 km of major water resources.

[Intext Question]

Religious Beliefs and Practices

- The elaborate architecture of graves, along with grave goods and other metal and stone objects, provides insights into the religious beliefs of megalithic people.

- Cult of the Dead: The megalithic people held a deep reverence for the dead, as evidenced by the effort and devotion put into constructing these monuments.

- They believed in an afterlife for the deceased, necessitating the provision of their needs by the living.

- Grave goods, reflective of the deceased's life, were buried alongside the mortal remains for use in the afterlife.

- This practice underscores the stronghold of the ‘cult of the dead’ in their culture.

- Grave goods symbolized the living's affection and respect for their deceased.

- Animism: Beliefs in animism are evident through animistic cults.

- Occurrences of animal bones from domestic animals such as cattle, sheep/goats, and wild animals like wolves in megaliths suggest that these animals were either killed for funeral feasts or sacrificed to provide sustenance for the dead.

- Animism is also reflected in terracotta figurines of animals adorned with garlands and ornaments.

- Sangam literature, contemporaneous with the later phase of megalithic culture in South India, sheds light on various methods of disposing of the dead practiced by megalithic people.

- Many earlier beliefs persisted during the Sangam age, and religious practices mentioned in Sangam literature partially reflect those of the megalithic people.

- The association of stone with the dead continued in South India, exemplified by herostones, Virakal, or Mastikal.

Polity

- Differentiation in the size of monuments and the nature of grave valuables suggests variations in status and ranking within the society.

- The construction of large monuments requiring considerable collective labor indicates the power of the buried individual to mobilize such resources.

- Given that contemporary societies were organized into tribal descent groups, it is likely that chiefly power, or chiefdoms, was prevalent during this period.

- The late phase of megalithic culture aligns with the Early Historical period, as evidenced by excavations at various sites.

- Literary texts from the Sangam period provide insights into this era, with tribal chiefs referred to as perumakan(great son) in these texts.

- Chiefs had control over the personal, material, and cultural resources of their clans, suggesting that elaborate burials were likely reserved for chiefs or heads of descent groups.

- Tribal power distribution was relatively simple, with chiefs, their heirs, and warriors enjoying privileged status.

- However, this status differentiation did not equate to a rigid social stratification.

- Evidence of a class-structured society is lacking in South India even by the mid-first millennium A.D., which is the upper date for the megaliths.

- The period of these large monuments likely spans the last two or three centuries before Christ.

- During this time, numerous small chiefdoms coexisted and competed with one another, laying the groundwork for the emergence of larger chiefdoms by the turn of the Christian era.

- Big chiefdoms also operated on clan kinship ties and a complex system of redistribution.

- References in Tamil heroic texts, such as Purananuru, indicate that even prominent chieftains were buried in urns.

- This suggests that all burials, including urn burials, signified individuals or groups with some level of status and ranking, such as heads of families or kinfolk.

- Memorial stones (natukal) were sometimes erected over the urn burials of great chiefs and warriors.

- However, the large multi-chambered rock-cut tombs are not mentioned in literary texts, possibly because their construction had become uncommon by that time.

- Some chiefdoms may have been larger based on their control over human resources, resource management, and exchange relations.

- Prestige goods and diverse ceramics found in graves attest to this.

- Megalithic people engaged in material and cultural exchanges with one another, with interactions at the clan level being need-oriented and use-value based.

- At the chief level, interactions were competitive, involving plundering raids both within and between clans, leading to the subjugation of one chief by another and the emergence of larger chiefdoms.

- These conflicts likely resulted in the deaths of many chiefs and warriors, explaining the proliferation of sepulchral monuments during the megalithic period.

- The rise of the cult of heroism and ancestral worship can also be attributed to these dynamics.

- Over time, through armed confrontations and predatory subjugation, the cultural and political power of certain chiefdoms evolved, leading to the emergence of bigger chiefdoms.

- The final phase of the megalithic period, contemporaneous with the Sangam period, marked the transition toward larger chiefdoms as described in Tamil heroic texts.

Legacy of the Megalithic Culture

Megalithism continues to be observed among various tribes in India, such as:- Maria Gonds of Bastar in Madhya Pradesh

- Bondos and Gadabas of Odisha

- Oraons and Mundas of the Chotanagpur region in Jharkhand

- Khasis and Nagas of Assam

Their memorial monuments include:

- Dolmens

- Stone circles

- Menhirs

The megalithic culture in Northeast India appears to have a South-East Asian influence rather than a Western one.

In South India, the remnants of megalithism among the Todas of Nilgiris are significant. Their current burial practices, which include features like grave goods (including food items) and stone circles marking burial sites, provide insights into the customs of the now-extinct megalithic builders of South India.

Limitations of the Sources for the Study of Megalithic Culture

The study of megalithic culture faces challenges due to the nature of available sources:

- Burial Evidence: Most evidence comes from burials, limiting our understanding of everyday life. Knowledge is restricted to grave furniture and inferences from grave architecture.

- Literary Evidence: Accounts from Graeco-Roman writers and ancient Tamil texts (Sangam literature) have limitations as they represent the later phase of megalithic culture.

- Excavations: Vertical digging at habitation sites provides limited evidence and cultural sequences.

- Lack of Settlement Remains: The absence of settlement remains associated with burials is a significant issue, especially in peninsular India. Regions like Kerala lack habitation sites, complicating the analysis of megalithic settlement patterns.

- Questioning of Megaliths: Some scholars even question the authenticity of megaliths as burial sites.

[Intext Question]

Foundational Phase of Peninsular India’s History

Megalithic culture can be viewed as a foundational phase in the history of peninsular India due to the following aspects:

- Beginning of Sedentary Life: Megalithic communities engaged in a mix of agriculture, hunting, fishing, and animal husbandry. Evidence of craft traditions and the presence of megalithic monuments suggest a shift towards sedentary living.

- Widespread Use of Iron: Iron objects outnumber those made of other metals. The variety of iron artefacts includes utensils, weapons, carpentry tools, and agricultural implements.

- Well-Developed Craft Traditions: Various types of pottery, bead making, and the presence of copper, bronze, silver, and gold artefacts indicate specialized craft traditions.

- Development of Metallurgy: Different metallurgical techniques were used in making metal artefacts, including casting, hammering, and alloying. Evidence of local iron smelting exists.

- Beginning of Trade: Some megalithic sites were centers of craft production linked to trade networks, as indicated by their locations along early historical trade routes.

- Rock Paintings: Paintings at megalithic sites depict various scenes, contributing to our understanding of the culture.

- Community Work: The construction of megaliths likely involved community effort and ritual practices significant to social and cultural life.

The ongoing practice of making megaliths among certain tribal communities in India further highlights the cultural legacy of this tradition.

|

347 videos|993 docs

|