Nixon and Watergate | UPSC Mains: World History PDF Download

What was ‘Watergate’?

At 2.30am on 17 June 1972, five burglars were discovered in the Democratic National Committee’s headquarters in the Watergate Hotel, about a mile from the White House. The break-in, which took place five months before the US presidential election, sparked a series of events that changed the course of the country’s history.

Why was this burglary different to any other?

The break-in was a bungled follow-up to a forced entry the previous month, when the same men stole copies of top-secret documents and wiretapped the phones. When the wiretaps failed to work, they returned to finish the job. An FBI investigation revealed all five had links to the White House, in a chain of connections that went as high as Charles Colson, special counsel to President Nixon, and showed them to be members of the Committee to Re-elect the President – nicknamed CREEP.

What was Nixon’s response?

Keen to distance himself from the scandal, Nixon declared no-one in the White House had been involved, but behind the scenes, he was involved in a massive cover-up. His campaign paid hundreds of thousands of dollars to the burglars to buy their silence. What’s more, in a flagrant abuse of presidential power, the CIA was instructed to block the FBI’s investigation into the source of funding for the burglary.

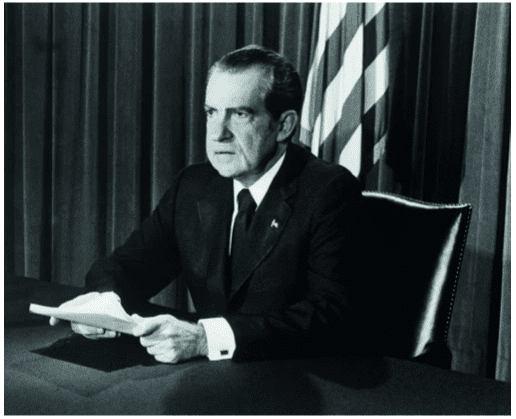

The President faces a prime-time national TV audience to deliver his historic words.

When did cracks start to appear in the cover-up?

Although Nixon won the election in November 1972, the scandal escalated. By the following January, seven men (‘the Watergate Seven’) went on trial for their involvement: five pleaded guilty, with the other two – former Nixon aides G Gordon Liddy and James W McCord – convicted of conspiracy, burglary and wiretapping. Soon after, a letter written by McCord alleged that five of the defendants had been pressured into pleading guilty during their trial. Others, too, began to crack under pressure. Presidential counsel John Dean, who initially tried to protect the presidency, was dismissed in April 1973 and later testified to the President’s crimes, telling a grand jury that he suspected conversations within the Oval Office had been taped. A tug of war ensued, with Nixon refusing to relinquish the recordings to Watergate prosecutors. But, in August 1974, following moves to impeach him, he did release the tapes. the Watergate cover-up and, on 8 August, he announced his resignation, the first US president ever to do so.

Was Nixon the instigator of the whole affair?

It’s unlikely Nixon himself orchestrated the break-in: a taped conversation between the President and his Chief of Staff has Nixon asking “Who was the asshole who did?”. But his role in covering up his administration’s involvement is unquestionable. At the time, however,Nixon was able to convince the public of his innocence and he won the election with 60.7 per cent of the popular vote.

The day’s papers signal Nixon’s imminent resignation. (Image by Getty Images)

What role did the media play in the President’s downfall?

The media was instrumental in keeping the scandal in the public eye, none more so than the Washington Post. Its reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein broke the most significant stories of the affair, and their investigation is credited with bringing down the President. Their story is portrayed in the 1974 book All the President’s Men, later a film.

Who was ‘Deep Throat’?

Woodward and Bernstein owe much of their success to a secret FBI source known as ‘Deep Throat’, who steered the pair in the right direction, allegedly urging them to “follow the money”. Deep Throat remained anonymous until 2005, when he was revealed as FBI number two, Mark Felt.

What were the consequences of Watergate?

Sixty-nine people were charged, with 48 found guilty, including Nixon’s Chief of Staff and Attorney General. Nixon continued to proclaim his innocence, declaring in 1977: “when the president does it, that means that it is not illegal”. He was eventually pardoned by President Ford, therefore escaping impeachment and prosecution.

|

50 videos|67 docs|30 tests

|

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|