UPSC Exam > UPSC Notes > Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes) > Perspectives on the Study Of Caste System

Perspectives on the Study Of Caste System | Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes) PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| G. S. Ghurye |

|

| M. N. Srinivas |

|

| Louis Dumont |

|

| Andre Beteille |

|

G. S. Ghurye

Writing on caste in the 1930s, G.S. Ghurye considered certain attributes as definite determinants of caste. For Ghurye, the following six attributes of caste held great significance.

- The Segmental Division of Society: Ghurye sees caste with reference to social groups where membership is acquired by birth and status. Social position was derived from the traditional importance of a caste. The segmental division of society refers to its division into a number of groups, each of which had a social life of its own and stood in a relationship of high or low to other castes.

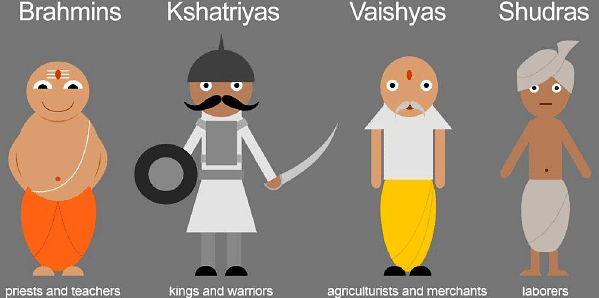

- Hierarchy: A second important attribute of caste followed from this. This is the attribute of hierarchy or the arrangement of the many segments of society according to a definite scheme. This scheme placed groups in positions of superior and inferior or high and low. There was an accepted rule of precedence in the ranking of groups such that Brahmins were placed on top and the untouchables at the bottom of the hierarchy.

- Restrictions on food, dress, speech and custom: According to Ghurye, the above two attributes reflected in the idea of separation. This separation between groups and maintenance of rank was maintained through restrictions on commensality or inter-dining, marriage, and also by keeping the high and low castes physically separated, placing restrictions on particular forms of dressing, speech and custom. What is meant is that the speech, dress and custom of the high castes could not be copied by the lower castes as by doing so they would be going against the governing rule of caste society. This is the rule that governs pollution and purification from its contagiousness.

- Pollution: The idea of pollution is a reference to something that is not pure or to the act of becoming impure by loss of purity. Such a loss of purity takes place through contact with polluting objects (such as faecal matter) or persons (such as Untouchables). The castes that were placed lowest were regarded as the most polluting. In fact the degree of pollution was reflected in disabilities suffered by a group; the most polluting castes were the most underprivileged. These disabilities took on many forms. They ranged from the caste being made to live outside the main village boundary, to a denial of access to village wells and temples. In fact, many villages were divided into streets where only particular castes could live and enter. For example, in the village of Kumbapettai in Tanjore, we find three main divisions of Hindu castes: Brahmin, the Non-Brahmin, and the Adi Dravida (untouchable). Each of these lived in different streets in the village, with the Brahmins in the North and the Adi Dravidas in the South of the village separated by paddy fields and a main road.

Similarly even the mere presence of person of low caste or his/her shadow was regarded as polluting. Thus, under the rule of the Marathas and Peshwas, the caste of Mahar (low caste agricultural labourers) was not allowed into the gates of Poona before nine a.m. and after three p.m. as at these times, shadows were too long and could unknowingly fall on a higher caste person and pollute him/her. In some areas particularly the Malabar region, lower castes could neither use nor carry anything that was part of a higher castes style of dressing. This included a restriction on wearing shoes, carrying an umbrella or wearing gold ornaments. - Occupational Association: According to Ghurye, every caste was associated with a traditional occupation.

Since a distinction was made between occupation being clean and unclean and therefore pure and impure, the hereditary occupation reflected a caste's status. For example, the Brahmins engaged in priesthood while the lower castes took up occupations such as those of the barber, cobbler, washerman etc. - Endogamy: Finally, every caste also maintained its rank and status jest by placing taboos not only on commensality, interaction and occupation but also upon marriage relations. Inter-marriages between castes were prohibited. Hence individuals married within the caste i.e. they practised endogamy. Every caste was fragmented into smaller subdivisions or sub-castes, and these were the units of endogamy. For example, the caste of Bania belonging to Vaishya rank divided into various sub-castes such as Shrimali, Porwal, and Modh. The Porwal sub-caste is further divided into Dasa and Visa. Marriage takes place between Dasa and Dasa.

M. N. Srinivas

Before we proceed to elaborate upon the contributions made by Srinivas to the study of caste attributes, you have to keep in mind one important fact. All scholars of caste are trying to explain the same social institution—the caste system. The criteria used for explaining are also the same — the attributes of a caste. There is however a difference between the works of these scholars. The basis of this difference lies in the nature of emphasis. What we mean is that while Hutton and Ghurye simply tell us what the various attributes of castes are and how these affect the relationships between castes. Srinivas and Dumont also look at these very attributes but with a different emphasis. For them it is not just the attributes of castes that have significance but the structure of relations that arise between castes on the basis of these attributes as well. The meaning of this will become clear to you as you go through the following sections.

Srinivas sees caste as a segmentary system. Every caste for him is divided into sub castes which are;

- the units of endogamy;

- whose members follow a common occupation;

- the units of social and ritual life;

- whose members share a common culture,

- and whose members are governed by the same authoritative body viz. the Panchayat.

Besides these factors of the sub-caste, for Srinivas, certain other attributes are very important. These are:

- Hierarchy: For Srinivas, hierarchy is the core or the essence of the caste system. It refers to the arrangement of hereditary groups in a rank order. He points out that it is the status of the top-most or Brahmins and the bottom-most or untouchables, which is the clearest in terms of rank. The middle regions of hierarchy are the most flexible as regards who may be defined as members of middle ranks. Srinivas in fact says that there are disputes about the mutual positions in the hierarchy. What is meant is that there may be four castes A, B, C and D placed in a hierarchy. One of these may not be ready to accept the place given to it, and seek an alternate rank or position. Further, there is no guarantee that the new position sought will be granted to a caste. For example, in South India, a group of smiths have claimed twice born status. They call themselves the Visvakarma Brahmins, but other castes resent this and even the Harijans do not accept drinking water from them.

Since the rank or status of a caste is closely related to its attributes, a desire to change one's position in the hierarchy means that a change must also be brought about in the nature of attributes. This attempt becomes basis of an important social process called Sanskritisation. - Occupational Association: Srinivas sees a close relationship between a caste and its occupation. He says that caste is nothing more than the “systematization of occupational differentiation”. Castes are in fact known by their occupations and many derive their name from the occupation followed (i.e. Lohar, Sonar, Kumhar, Chamar, Teli etc.). He also stresses that occupations are placed in a hierarchy of high and low.

- Restrictions on Commensality, Dress, Speech and Custom: These are also found among castes. There is a dietic hierarchy and restrictions on acceptance of food.

- Pollution: The distance between castes is maintained by the principle of pollution. Srinivas too argues that the high castes must not come into contact wi th anything that is polluting, whether an object or a being. Any contact with pollution renders a caste impure and demands that the polluted caste undergo purification rites. If pollution is serious such as when a high caste person has sexual relations with an untouchable, the person involved may be removed from his/her caste.

- Caste Panchayats and Assemblies: Besides the above mentioned attributes of a caste, every caste is subject to the control of an order maintaining body or a Panchayat. Elders of each caste in a village together maintain the social order by exercising their authority collectively. Further, every caste member is answerable to the authority of its caste assembly. The authority of a caste assembly may extend beyond village boundaries to include in its jurisdiction caste members in other villages.

From the above we can see that the attributes of a caste definitely determine the nature of inter-caste relations. It is these caste attributes or customs that also determine the rank of a caste. This becomes most obvious in Srinivas' work on caste mobility or Sanskritisation.

Sanskritisation

- We have already seen how every caste is assigned a position in the caste rank order on the basis of the purity or impurity of its attributes. In his study of a Mysore village, Srinivas found that at sometimes or the other, every caste tries to raise it rank in the hierarchy by giving up its attributes and trying to adopt those of castes above them. This process of attempting to change one's rank by giving up attributes that define a caste as low and adopting attributes that are indicative of higher status has been called Sanskritisation. This process essentially involves a change of one's dietary habits - from non vegetarianism to vegetarianism, and a change in ones occupational habits, from an unclean to a cleaner occupation.

- We began this section by mentioning how for Srinivas, more important than the attributes was the structure of relations that arises around castes. What this means is that the attributes of a caste become the basis of interaction between castes. The creation of patterns of interaction and interrelations is best expressed in Srinivas' use of concept of the dominant caste. Let us read something about this.

Dominant Caste

- To the already existing general attributes of castes, three other important ones are added. These are

(i) Numerical strength;

(ii) Economic power through ownership of land; and

(iii) Political power. - A dominant caste accordingly is any caste that has all three of the above attributes in a village community. The interesting aspect of this notion is that the ritual ranking of a caste no longer remains the major basis for its position in the social hierarchy. Even if a caste stands low in the social hierarchy because of being ranked thus, it can become the dominant, ruling caste or group in a village if it is numerically large, owns land and has political influence over village matters. There is no doubt that a caste with relatively higher ritual rank would probably find it easier to become dominant. But this is not the case always.

- We take an example from village Rampura in Mysore to illustrate the above. In this village there are a number of castes including Brahmins, Peasants and Untouchables. The peasants are ritually ranked below the Brahmins, but they own almost all the land in the village, are numerically preponderant and have political influence over village affairs. Consequently, we find that despite their low ritual rank, the peasants are the dominant caste the village. All the other castes of the village stand in a relationship of service to the dominant caste i.e. they are at the beck and call of the dominant caste. We give you another example to illustrate this.

- In the village of Khalapur in North-Western Uttar Pradesh, in the 1950s there were thirty-one castes. The Rajput (Kshatriya rank) of Khalapur was the dominant caste as Rajputs had numerical strength and composed forty-two percent of the village population; they had economic power since they owned and controlled ninety percent of the village land; and political power since all the lower castes had to do their bidding. The Brahmins on the other hand were not dominant because they had none of the characteristics of dominance. The villagers believed that Khalapur belonged to the Rajputs even though they ranked below the Brahmins in terms of their ritual status. From the above we see that in Srinivas' view, economic and political factors go hand in hand. Those who have economic influence have political power and use this combination of the economic and the political power to improve their social rank in the social hierarchy. It is this very combination of attributes which is used by a caste in its attempt to sanskritise itself and improve its social rank.

Louis Dumont

- A clear statement of caste attributes and how these function to create structures or patterns of interactions is to be found in the work of the French scholar Louis Dumont. In his book Homo Hierarchicus (1970), Dumont also attempts an understanding of the caste system.

- For Dumont, the starting point of the understanding of the caste system is Bougle's work. The major emphasis here is therefore put upon three major attributes of caste, namely

(i) hierarchy

(ii) separation

(iii) division of labour.

The underlying principal of the caste system for Dumont is the principle of the opposition of the pure and the impure. - Although Dumont also sees castes as segments, for him this does not mean that a caste is simply divided into sub-sections where each is independent of the other. On the other hand each segment is a part of the segment above it. This is somewhat like an onion. You peel off one layer and find another and yet another beneath it and so on. All the layers put together make up the onion.

- Dumont sees the caste system as a combination of segments. Each of the segments stands in a relationship of hierarchy to the other; nevertheless, it is inclusive of the other. The terms that Dumont uses for this inequality and relationship between castes is 'the encompassing and the encompassed'. This means that every caste in the hierarchy includes the one below it in its character, i.e., Brahmin position by itself has no meaning. Even though superior to the Kshatriya, it is in relationship and opposition to the latter that the Brahmin has ritual superiority.

- This brings us to the second important attribute of caste for Dumont, namely, separation which is both expressive of the pure or impure rank of a caste and at the same time helps maintain the ritual status of a caste. In fact this separation between castes and the need to keep it thus, is made possible by the division of labour and traditional association of every caste with an occupation which it specializes in and-also monopolizes. The principle of purity and pollution is the bases of the relationship that arise between castes in the spheres of commensality and marriage.

- Restrictions on who one eats with and who one marries are based on the pure or impure rank of the castes involved in the relationship. Only pure castes or castes ranked high or as equals are considered for commensal or marriage relationship.

- These relationships are thus determined by the attribute of purity or impurity of a caste. They also are expressive of a separation and hierarchy between castes.

- Dumont was deeply influenced by the French intellectual milieu of his times. His study of caste system titled Homo Hierarchicus was first published in French in the year 1967 and later translated into English in 1969. For Dumont, equality and inequality are contrasting concepts. He considers egalitarianism to be the value of the West and hierarchy to be the value of the East. Dumont says that caste is not a form of stratification, like class for example. For him, caste is a special form of inequality, whose essence has to be deciphered by the sociologist. Relationships between castes take place on the basis of certain mental assumptions, which constitute the essence of caste. Dumont identifies hierarchy as the essential value underlying the caste system, supported by Hinduism. This value of hierarchy not only ranks people differentially, but also holds together this complex Indian society. In other words, hierarchy is a value system which integrates our society.

- To begin with, let us see how Dumont defines caste. Dumont's definition of caste heavily draws from Bougle. For Bougle, the caste system denotes the following:

(i) a large number of permanent groups;

(ii) these groups are specialized;

(iii) they are separated from each other;

(iv) these groups are tied up by a hierarchical relationship - Dumont says that at the base of these principles stands a basic principle, i.e., opposition of the pure and the impure. Pure is superior to the impure and has to be kept separate. Says Dumont (1970:43) "whole is founded on the necessary and hierarchical co-existence of the two opposites". The caste system appears to be rational to those who live in it, because of the opposition between the pure and the impure. For example, in a village, you might find both Brahmins and the untouchables. Brahmins are pure and hence supreme and live at the heart of the village whereas the untouchables are considered as impure and hence live outside the village.

- Hierarchy in India, says Dumont indicates gradation but not power and authority. Hierarchy is the principle through which the elements are ranked in relation to the whole. In many societies it is religion which provides an understanding of the whole, and thus ranking is basically religious in nature. In the Varna system there are four categories and the category of untouchables. These four categories are divided into two - Shudras and others. Then the category of others is divided into two opposing groups - Vaisyas and others. Finally there is an opposition between the Brahmins and the Kshatriyas. In India, status (Brahmin) has always been separated from power (King). Not only that, power has been subordinated to status. The King is always subordinate before the Priest. This also means that spirituality has never been given a political chance in India. In many western religions, religious heads wield power also. The Pope, head of Catholic Christians, is a spiritual head and at the same time he is head of his kingdom, the Vatican City.

- In Indian society, the King is subordinate to the Priest. But together; the y have dominion over the world. The King and the Priest are also dependent on each other. The King can order a sacrifice but only a Priest can perform it. Elsewhere it was mentioned that status is superior to power and there exists a fundamental opposition between pure and the impure. Hierarchy is something ritualistic in nature and supported by religion. Only when power is subordinated to status, this kind of pure hierarchy can develop. The Brahmin, who personifies purity and hence is superior, encompasses the whole system. But a Brahmin along with the King opposes all the other categories of the Varna system.

- If you have read the above arguments of Dumont carefully, you will be able to compare the views of Dumont and other scholars who practice the interactional approach. Whereas other interactional theorists talk about a ritual hierarchy and secular hierarchy, Dumont talks about only one, i.e., ritual hierarchy. In fact, for Dumont, a secular hierarchy does not seem to exist because hierarchy itself is religious (ritual) in nature. For example, the Jajmani system understood by many scholars as an economic arrangement is just a religious arrangement (ritual expression) for Dumont. In this section, we have seen how Dumont provides a new way of studying the caste system focusing on the ideology or value system underlying caste. Dumont sees it based on the fundamental opposition between pure and impure. For Dumont, hierarchy is basically of a ritual character.

- The Jajmani system, says Dumont (1970) “makes use of hereditary personal relationships to express the division of labour.” Each family has a family at its disposal to provide the specialized services. A washerman family might render its service to another (high) caste family regularly throughout the year. A Shudra family might be under obligation to render services to a high caste family in their farm. These services are personalised and a good part of the wages are in kind (grains). During festivities, the servicing castes may get special clothes or a share in the harvest.

- The Jajmani system basically is a form, of division of labour. In Indian villages, there are generally two kinds of castes: those who, own land and those who do not. Those who own much land also wield considerable amount of influence and power in the local context (i.e. village). This dominant caste in former times performed the functions of the king locally, but itself was subordinate to the King of the region. Now, to this dominant caste several 'dependent castes' are attached to perform various functions. These dependent castes earn their subsistence through specialised services rendered to the dominant caste. The untouchables and the specialised castes (e.g. washerman, barber, etc.) are under strong obligation to render personal services to the dominant caste.

- Now, Dumont says that the Jajmani system is a ritual expression rather than just an economic arrangement. Dumont says that the Jajmani system is governed by a specific set of ideas. These ideas are capable of imposing limits on the economic power. The principle of hierarchy which determines who is dominant and dominated, justifies the positions of these groups. This principle directly opposes economic activities. In any economic activity the individual has to be the unit. But in the Jajmani system, the village is the unit. Service is rendered by the dependent castes to the community, not just to an individual. Service to the village community by dependent castes is regarded as necessary for ensuring order in society. This view, where there is an ordered whole where each caste is assigned its place, is basically religious in character. Thus, Jajmani system of division of labour is not an economic arrangement or secular interaction. Jajmani system is the religious expression of interdependence, where interdependence itself is derived from religion. Thus, Dumont provides a very different way of looking at the Jajmani system by focusing on the value system underlying it.

Commensal Transactions

- Commensal transaction, according to Dumont, denotes the organisation of the caste system. The rules regarding commensal transactions are effectively related to the ranking of castes and the division of labour. They are also linked to the idea of purity. The ranked or stratified interaction between castes reveals the type of contacts avoided as impure. The gradation of food is linked up with the classification of individuals into groups and the relationships between them. Gradation of foodstuffs, in other words, mirrors the stratified reality.

- Regarding commensal transactions, purity of the consumer, consuming place and the occasion becomes important. On certain grand occasions like weddings, Brahmin is the cook, so that a large number of castes can eat in the wedding banquet. Everyday food is distinguished from food for banquets. The question of purity, it must be noted, does not arise in all situations. For instance, washerman is a purifier and may come to the house freely. But when he comes to marriage, to supply the fabrics available with him, he pollutes the situation.

- Thus, we understand that, according to Dumont, commensal regulation emphasise hierarchy rather than separation. They also draw on the idea of purity but become crucial within specific circumstances.

Criticisms of Dumont's Approach

- An oft-repeated criticism against Dumont's work is that, his theoretical system is not sensitive enough to history. In other words, the features of the caste system as projected by Dumont seem to be unchanging. In reality the caste system has changed in various ways down the ages. Also, Dumont seems to characterize Indian society as almost stagnant, since the places much emphasis on the integrative function of caste system.

- As have seen earlier, Dumont makes a clear separation between power and status. How far this is another question. Berreman (1971) argues that power and status could be two sides of the same coin as well. He cites the case of the Gonds. The gonds wherever they have had power in the form of land, have adopted hierarchical symbols of behaviour to justify that status. The purity versus impurity opposition highlighted by Dumont is also not universal. In certain tribal societies status is not anchored in purity but in sacredness.

- Moreover, Dumont's view of caste as a rationally ordered system of values (ideology) has also been questioned. Dumont seems to have ignored the number of protest movements which emerged in Indian history questioning the ideology of the caste division itself, through his emphasis on values. Dumont could not see the relationship between castes as conflict ridden. For him, the relations between Varna, especially the Brahmin and Kshatriya are almost complementary.

Andre Beteille

- Andre Beteille defines caste as follows: “Caste may be defined as a small and named group of persons characterized by endogamy, hereditary membership, and a specific style of life which sometimes includes the pursuit by tradition of a particular occupation and is usually associated with a more or less distinct ritual status in a hierarchical system”.

- Beteille’s writings have focussed on the changes in the caste system in the post independence period of Indian history.

Change from closed system to open system

- In his study of Caste, Class and Power: Changing Patterns of Stratification in a Tanjore Village, Andre Beteille (1966) wrote that earlier (i.e. in pre -British period) education was a virtual monopoly of the Brahmins who dominated this area. But at the time of his study, the educational system had become far more open, both in principle and in practice. Many non-Brahmin and even untouchable boys attended the schools at Sripuram (the village studied by Beteille) and the adjacent town of Thiruvaiyur. Because of this education, the non-Brahmins and the Adi-Dravidas (the lowest castes) could compete on more equal terms with the Brahmins for white-collar jobs. It also helped them to participate in the political affairs more equally with the Brahmins.

- According to Beteille, in the towns and cities white-collar jobs were relatively castefree. Non-Brahmins from Sripuram could work as clerks or accountants in offices at Thiruvaiyur and Tanjore along with the Brahmins.

- Within the village, land had come into the market since, due to several factors, some of the Brahmins had to sell their land. This enabled the non-Brahmins and even a few Adi-Dravidas to buy it. Thus, as land came into the market, the productive organisation of the village tended to become free from the structure of caste.

- Beteille had come to the conclusion that in a way changes in the distribution of power was the most radical change in the traditional social structure. He said that the traditional elites of Sripuram, comprising the Brahmin landowners, had lost their grip over the village and the new leaders of the village depend for power on many factors in addition to caste. There had come into being new organizations and institutions, which provided new bases of power. These organizations and institutions were at least formally free of caste.

- Beteille has also dwelt on the paradoxical weakening and strengthening of the caste system post independence in one of his public lectures.

(Following pages contain the transcript of a Lecture titled ‘Caste Today’ delivered by Prof. Andre Beteille)

Caste Today

By Andre Beteille

- In the 1950s’, 60s’ and 70s’, caste was the subject of academic interest, not necessarily a subject of very wide public interest. Today, it has become a subject of public interest and I would like to give some thought as to how this has happened. How a subject, whose study was confined to a specialized group of academics in the field of social anthropology and sociology, has now captured the public imagination? What does it indicate about the changes in our society?

- As a student of the society, I have been struck very much about the change in perceptions that have come about since 1977. I think the year 1977 was a kind of watershed in the public attention that began to be paid increasingly to caste and its operations in public life. Today, it is a subject which receives an enormous amount of attention from the media, both print and electronic. As you go back to the newspapers of the 50s’ and 60s’ and even the 70s’, you will not find caste receiving the kind of attention that it receives in the newspapers, in the popular magazines and particularly on television.

- Today, people talk and debate endlessly about caste bias in education and employment – about how far does caste bias prevail in the admission of students or in the appointment of the faculties in our universities and centres of excellence? To what extent are the admissions and appointments in institutions like IITs and AIIMS, JNU and University of Delhi governed by the caste bias. To what extent are the actual operations of everyday activities in these institutes governed by caste considerations?

- When I go back to my own experience of the Delhi School of Economics (DSE) in the University of Delhi, to which I came as a lecturer in 1959, the subject of caste was considered rather boring, particularly by my colleagues in DSE, who believed that caste belonged to India’s past, not to India’s future. These people felt that caste was a subject of highly specialized interest with which intelligent people, who were concerned with the transformation of Indian society, should not preoccupy themselves too much.

- I was derided by some of my progressive friends, particularly in the profession of economics for taking so much interest in what they considered to be a ‘reactionary’ subject. Their feeling was, in the 50s’ and 60s’, if you are interested in the roots of inequality and conflicts in Indian society, then you should look to ‘class’ and not to ‘caste’.

- But the same people who tended to dismiss caste as an epiphenomenon, as the matter of the superstructure, rather than as being at the heart of inequality and conflict in Indian society, have today turned with new interest and tend to put caste at the centre of attention.

- Today, caste bias is very widely discussed in Delhi University. Today, if you go to Delhi University and ask about admissions; within five minutes you will come to the point where people will tell you that all of this is, in fact, done in terms of caste. They will tell you that caste is very important in the operation of our public institutions, whether in education or in employment. I don’t know to what extent this is actually true. My sense is, that caste bias certainly exists even in our public institutions, though this tends to be somewhat exaggerated by the media.

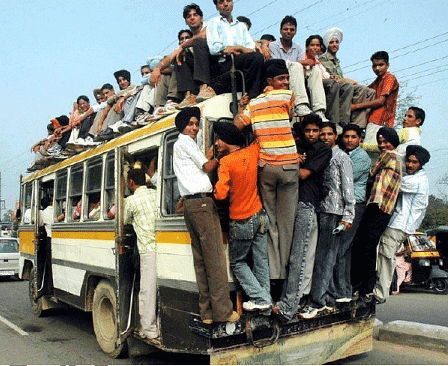

It is impossible to follow caste rules governing distance maintenance from ritually lower castes in public transport in urban India

It is impossible to follow caste rules governing distance maintenance from ritually lower castes in public transport in urban India - Then the media are full of reports about caste conflicts, including violent ones, in the villages, towns and sometimes even in the cities. Now, it might happen that caste conflicts prevailed even in the past but they were not reported as frequently in the press as they are done now.

- When one is talking about electoral politics in most parts of India, the caste equation figures very much in electoral calculations. This is what which keeps the subject of caste alive in the media, in public debate and in public discussions. Certainly, the perception that caste is important has become much more widespread among the intelligentsia, academics and journalists.

- Now, certainly if one goes by what one sees in the media, one will have to admit that caste is still very much here. And this perception of the Indian society is very different from the perception that the forward looking and progressive Indians had in the wake of independence. Certainly they believed in Nehru’s India that caste was on its way out; rather than becoming progressively stronger with the passage of time.

- It’s not that everybody subscribed to the general optimism that caste was on its way out and that it would soon be a thing of the past. There were exceptions and I will draw attention to one or two of them, whose writings, even in the 50s, drew attention to the fact that caste was very much a part of the Indian reality in post independence era. And this point was made very forcefully by a person who dominated sociological studies in India in the second half of the 20th century M.N. Srinivas.

- Srinivas, in his presidential address to the Anthropology & Archaeology Section of the Indian Science Congress, in 1957 argued that we have not seen the last of the caste system and that it was still alive and kicking and we better take note of it. There was an editorial in the Times of India commenting on that Presidential Address that this is very greatly exaggerated, this is something which is dying out and the eminent social anthropologist was bringing it back to life. And I remember the response to Srinivas’ views in the Indian Statistical Institute where I had my first job. People tended to deride this preoccupation with caste, in a similar vein, when I talked to economists in the Delhi School of Economics in 1959. The economists, with whom one discussed these issues, whether it was Shri K.N. Raj, P.N. Dhar or V.M. Dandekar, were inclined to argue that this was not something which we should worry too much about.

- Now the question I would want to ask myself is that, were these distinguished economists, academics, journalists who believed that caste was in decline, completely deluded? Were they unable to see what was going on in the Indian society? Frankly, I don’t think they were wholly deluded.

- Because there are many areas of social life in this country in which there is a secular trend of decline in the significance of caste. I would pick out three areas and argue that there is substantial evidence that caste is in decline in all these three fields of social life or action. The evidence does corroborate that caste has been steadily in decline in three of the most significant areas of social life where it held forte until the end of the 19th century.

- First, is the area of religion and ritual. Second, is the area of inter-marriage and third is the area of the association with the caste and occupation.

- If you look at the literature on caste till the time of independence, much of it highlights the importance of ritual observation of purity and pollution as the basis of the divisions and hierarchies of caste. Particularly, the writings of civil servants like Edward Blunt, J.H. Hutton and missionaries drew attention to the great strength of the opposition of purity and pollution as a basis for hierarchies of caste.

- For instance, the rules for the interchange of food and water. What kind of food is acceptable from whom? From which caste, water is acceptable and on this issue, there are enormous ritual variations. There are detailed accounts, particularly in South India about the physical distances that different castes had to maintain from each other, depending on the ritual status in the hierarchy. I don’t think that there is any doubt that this has been weakening steadily and there has been a secular trend of decline in the ritual basis of caste.

- The practice of untouchability, however, continues. I won’t say that it has disappeared. But I would say that the ritual aspects of the practice of untouchability are no longer as prominent. The practice of untouchability in the traditional ritual sense of the term is being replaced by the practice of atrocities against untouchability.

- I have seen this change in my own eyes in a village in Tanjore district which is the citadel of Brahmanical orthodoxy; when I lived in the Brahmin dominated quarters of the village known as Agraharam. I found my way to the Agraharam. When I used to be there in 1961-62; there was a clear residential segregation in these villages during the time. In the Agraharam only the Brahmins lived. At the other extreme you had the Cheris where lived the Dalits, the Adi-Dravidas and the Harijans. In between, there was the area where the non-Brahmins lived. And then, you could identify a Brahmin by his appearance, by how he dressed etc. All this has changed and this, I believe is also an important and a secular trend of change.

- I have no doubt whatsoever that what was once considered to be absolutely crucial to the functioning of caste system is now in complete or almost disarray; not so much in the rural areas, and in fact, there are orthodox persons at North and South India who would think five times before employing a Harijan woman as a cook or even before allowing him to use the kitchen. But I think this trend/direction of change is quite clear.

- The rules and restrictions on marriage are considered the real heart of the caste system. Of course, they were very extensive and very elaborate. I won’t say that the rules of caste endogamy have disappeared. I think that marriage is one area in which people look to match caste with caste. I have known quite a number of very liberal, highly educated, even left oriented intellectuals who said that caste does not exist in Indian society any more, but when they are looking for a bride or a groom, they are quite aware of the caste of the person. But while that is there, there are also changes.

- I would draw attention to two or three kinds of changes. One is that the rules or restrictions on marriage or the rules of the marriage within the caste system were not simple. They were quite elaborate and complex. We tend to think of the rules of caste marriage only in terms of the rules of endogamy i.e, when one marries within one’s own caste. But that was not the only rule that prevailed; there was also the rule of hypergamy which in Sanskrit, is known as Anuloma, i.e, a man of a superior caste may marry a woman of lower caste; but, never the other way round. Anuloma was allowed but never Protiloma. Anuloma is sanctioned; Anuloma is considered to be necessary, is socially deemed to be quite in order. But not Protiloma. And rules of hypergamy were very widely practised. We, the Brahmins, to which community my maternal ancestors belonged, were notorious for the practice of Anuloma. And that enabled the men to accumulate larger number of wives and along with that they could also accumulate large sums in dowry.

- Now inter-caste marriages do take place and I would explain in what way, but the point is that the inter caste marriages did take place even in the past but according to certain very specific rules, viz., that the man had to be of superior caste and the woman of inferior caste. Today when inter caste marriages take place or when that is allowed, and tolerated, people do not want to find out, whether it is Anuloma or it is Protiloma. And inter caste marriage today is truly an ‘inter caste’ marriage. And I have tested this way with my own students, in Delhi University, students from this city of Calcutta. They are mainly uppercaste Bramhin girls, I would ask them from time to time, “ Tomader barite Anulom biye hoyeche”? Protilom biye hoyeche”? And they don’t know the meanings of these words. These words have lost their meaning and significance. I think that is not unimportant.

- Are inter-caste marriages taking place ? Yes, but how widespread are they, I don’t really know. We don’t have reliable or adequate statistics to tell us how widespread inter caste marriages are. But inter caste marriages are taking place. However, even when inter caste marriages do take place, one has to recognize the fact that these marriages were usually between adjacent sub-castes of the same caste.

- Let’s say the marriage between a Radi bride and a Barendra groom which would be considered improper and unacceptable in my grandmother’s generation, is today, merely a marriage within the Brahmin community. Inter caste marriages are also acceptable, provided the distance between the two castes is not very great; let’s say that, between Brahmin – Baidya or between Baidya and Kayastha. Intercaste marriages between them are much more widespread now than that was before. The trend is quite clear that the rules restricting inter-caste marriages are not becoming more stringent, but are becoming more lax.

- But one must not ignore the fact that if an inter-caste marriage is between an upper-caste man and a dalit woman, then the sanctions are likely to be very swift and not, if it is the other way round; because there is a strong bias for Anuloma in the caste system and strong bias against Protiloma in the caste system. I think that runs very deep in the structure of Indian society. It is not just a matter of caste. The idea that the status of the groom should be superior to the status of the bride is very strong and ingrained in the society. So inter caste marriages are taking place but not necessarily across great structural distances.

- But the other important thing which deserves our notice is not simply the frequency of inter caste marriages. One might say that to be one in one thousand, but even that would be quite significant compared to the past. It’s not the frequency, but one has to take into account the sanctions against inter caste marriages; because one must ask, even if there are three inter caste marriages, what is the consensus, what is the sanction against inter caste marriages? There were very powerful sanctions of the community against inter caste marriages in the past. These community sanctions have ceased to exist and whatever sanctions are there, are those imposed within the family or the joint family at the most. So, that again, is an important change.

- The third area where the caste seems to be weakening and again where there is a secular trend, is in the association between caste and occupation. Earlier, many argued that the real foundation of the caste system lay in the association between caste and occupation. I would say that there is still some association between caste and occupation but it is weakening. If one wants to understand, what is the association between caste and occupation, then I think one has to examine it at two different levels.

- First of all, there was a very specific association between caste and occupation of the kind which was studied in very great detail by my own teacher, Prof. N.K. Bose. For instance, he pointed out that among oil pressers, the Telis, there were two or three different sub-castes of Telis and each of these sub-castes practised oil pressing using their respective techniques. There are oil pressers who use one bullock for running the oil mill and there are those who use two bullocks for running the same. Similarly for potters and those engaged in other occupations. It is a kind of monopoly that goes down right to the details of the craft or the service. Now that kind of specific association between caste and occupation is very definitely in retreat because many of those old occupations, crafts and techniques are now dying out.

- But apart from the specific association between caste and occupation, i.e., a sub-caste pursuing a particular craft in a particular manner, there is also a general association between caste and occupation, i.e, caste belonging to the higher levels, usually practice superior non-manual occupation and castes of lower levels were usually relegated to the inferior, manual and menial occupations and that association is still quite noticeable. It has not yet disappeared, although it has been curbed quite a bit.

- Now the factor behind loosening up of the association between caste and occupation is the emergence of a very large number of new caste-free occupations. There are new occupations to which there is no appropriate caste or sub-caste. There are no particular castes or sub-castes which match the new occupations that are emerging before our eyes at a very rapid rate.

- So, I have been arguing that in three very important areas, caste does seem to be in retreat so that my friends in the Delhi School of Economics like Shri K.N. Raj, Amartya Sen or Sukhomoy Chakraborty, when they were saying that the caste is in decline, it was not altogether an illusion. It was in decline in that sense but why is it that people have acquired a renewed interest in caste?

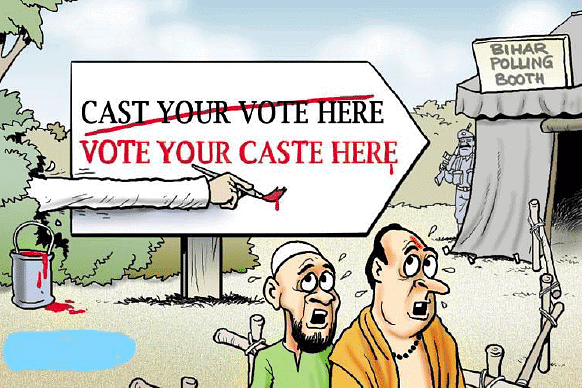

- I would say if caste has been given a new lease of life in Indian society, it is the political system which has given it. Srinivas’ paper ‘Caste in Modern India’ is a strong pointer to the continuing existence of the caste system and even to its strengthening. There is no doubt at all that democratic politics has given a new lease of life to caste by allowing caste to be used as a basis for mobilizing electoral support. This is what is described as identity politics.

- So Srinivas was right and so also K.N. Raj was right. When K.N. Raj was arguing that caste is weakening, he had in mind the association between caste and occupation, the very stringent rules restricting inter-caste marriages and the rules regarding ritual inclusion and exclusion; so he was right. But when Srinivas was arguing that caste had been given a new lease of life, he was also right.

- I came to appreciate the significance of caste in politics in 1961 and 1962 because that was when I was doing my field work in Tanjore district in Tamil Nadu. In 1962 the third General Election was held and I saw that caste was entering as a factor in villagers’ calculations -- about who will win and why is a party setting a particular person as one of its candidates. And I came to Delhi and talked about this phenomenon with politicians. When you asked the politicians that caste after all was useful in mobilizing support in elections, they would say, at first, “we don’t do it, the other parties do it”. And then when you show evidences and point out that their party also does it, they would say “Well Mr. Béteille! This is politics. I am not a professor like you, we have to be realistic. If other parties are using caste, what do you expect of us?” So the use of caste formobilizing political support was always justified on pragmatic grounds-- “We have to do it because everyone was doing it”.

- It is here that a change came about in 1977 and in 1990. The use of caste in politics today is no longer justified only on pragmatic grounds; it is also justified on ideological grounds- by an appeal to social justice. You look at the distribution of resources, whether in education or employment, there is no alternative but to use the loyalties of caste for mobilizing political support. Even the left parties are no different from the other parties in justifying the use of caste in identity politics.

- Of course, people may point out to me that caste was given a new lease of life only by the political process for mobilizing electoral support but I would argue that if there were nothing to it, how could one have used caste for mobilizing political support? It is not that the people were not conscious of their caste identity; of course they were and this comes up when one talks about marriage. But this consciousness was weakening and it has been given a new lease of life and strengthened as a result of identity politics which has been in vogue since 1977, but particularly since the Mandal agitations of early 1990s.

- So, this is where we stand now, and I don’t know what the future of caste is.

In finality, one must always be very sensitive to regional variations in India. I find it extremely difficult to generalize for the whole of India when I am talking about the power played by caste in politics or in ritual or in inter- marriages in certain parts of the country. There are enormous regional variations, those between rural India and urban India, etc.

The document Perspectives on the Study Of Caste System | Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes) is a part of the UPSC Course Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes).

All you need of UPSC at this link: UPSC

|

120 videos|427 docs

|

FAQs on Perspectives on the Study Of Caste System - Sociology Optional for UPSC (Notes)

| 1. What are the main perspectives of G. S. Ghurye on the caste system in India? |  |

Ans.G. S. Ghurye viewed the caste system as a complex social institution that has evolved over time. He emphasized the historical and cultural dimensions of caste, arguing that it is deeply rooted in Indian society. Ghurye believed that caste is not merely a rigid hierarchy but also a dynamic system influenced by various social factors. He highlighted the significance of caste in shaping social identities and relationships in India.

| 2. How did M. N. Srinivas contribute to the understanding of the caste system? |  |

Ans.M. N. Srinivas introduced the concepts of "dominant caste" and "sanskritization" to explain the dynamics of the caste system. He argued that certain castes can achieve a position of dominance through social mobility and cultural assimilation. Srinivas's work emphasized the fluidity of caste relations and the ways in which lower castes could elevate their status by adopting the customs and practices of higher castes.

| 3. What role does Louis Dumont play in the study of the caste system? |  |

Ans.Louis Dumont is known for his structuralist approach to the caste system, particularly in his work "Homo Hierarchicus." He argued that caste is a fundamental aspect of Indian society, characterized by a hierarchical structure that reflects broader social values. Dumont emphasized the ideological underpinnings of caste, suggesting that it is not just a social arrangement but also a worldview that shapes the behavior of individuals within the society.

| 4. What insights does Andre Beteille provide regarding caste and social stratification? |  |

Ans.Andre Beteille offered critical insights into the complexities of caste and social stratification in India. He argued for a more nuanced understanding of caste that takes into account factors such as class, power dynamics, and economic changes. Beteille emphasized the importance of empirical research in studying caste and cautioned against oversimplified views that ignore the changing realities of caste in contemporary society.

| 5. How do these scholars' perspectives on caste contribute to the UPSC syllabus? |  |

Ans.The perspectives of G. S. Ghurye, M. N. Srinivas, Louis Dumont, and Andre Beteille are integral to the UPSC syllabus as they provide a comprehensive understanding of social structures in India. Their theories and findings help aspirants analyze the historical, cultural, and socio-economic dimensions of caste, which are essential for topics related to Indian society, social justice, and contemporary issues in governance and policy-making.

Related Searches