Problems in Africa- 2 | UPSC Mains: World History PDF Download

Angola: A Cold War Tragedy

(a) Civil war escalatesDescribed how Angola was engulfed by civil war immediately after gaining independence from Portugal in 1975. Part of the problem was that there were three different liberation movements, which started to fight each other almost as soon as independence was declared.

- The MPLA (People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola) was a Marxist-style party which tried to appeal across tribal divisions to all Angolans. It was the MPLA which claimed to be the new government, with its leader, Agostinho Neto, as president.

- UNITA (National Union for the Total Independence of Angola), with its leader Jonas Savimbi, drew much of its support from the Ovimbundu tribe in the south of the country.

- FNLA (National Front for the Liberation of Angola); much weaker than the other two, it drew much of its support from the Bakongo tribe in the north-west.

Alarm bells immediately rang in the USA, which did not like the look of the Marxist MPLA. The Americans therefore decided to back the FNLA (which was also supported by President Mobutu of Zaire), providing advisers, cash and armaments, and encouraged it to attack the MPLA. UNITA also launched an offensive against the MPLA. Cuba sent troops to help the MPLA, while South African troops, supporting the other two groups, invaded Angola via neighbouring Namibia in the south. General Mobutu also sent troops in from Zaire to the north-east of Angola. No doubt there would have been fighting and bloodshed anyway, but outside interference and the extension of the Cold War to Angola certainly made the conflict much worse.

(b) Angola and Namibia

The problem of Namibia also complicated the situation. Lying between Angola and South Africa, Namibia (formerly German South West Africa) had been handed to South Africa in 1919 at the end of the First World War, to be prepared for independence. The white South African government had ignored UN orders and delayed handing Namibia over to black majority rule as long as possible. The Namibian liberation movement, SWAPO (South West Africa People’s Organization), and its leader, Sam Nujoma, began a guerrilla campaign against South Africa. After 1975 the MPLA allowed SWAPO to have bases in southern Angola, so it was not surprising that the South African government was so hostile to the MPLA.

(c) The Lisbon Peace Accords (May 1991)

The civil war dragged on right through the 1980s until changing international circumstances brought the possibility of peace. In December 1988 the UN managed to arrange a peace settlement, in which South Africa agreed to withdraw from Namibia provided that the 50 000 Cuban troops left Angola. This agreement went ahead: Namibia became independent under the leadership of Sam Nujoma (1990). The end of the Cold War and of communist rule in eastern Europe meant that all communist support for the MPLA ceased, all Cuban troops had gone home by June 1991, and South Africa was ready to end her involvement. The UN, the Organization of African Unity (OAU), the USA and Russia all played a part in setting up peace talks between the MPLA government of Angola and UNITA in Lisbon (the capital of Portugal). It was agreed that there should be a ceasefire followed by elections, to be monitored by the UN.

(d) The failure of the peace

- At first all seemed to go well: the ceasefire held and elections took place in September 1992. The MPLA won 58 per cent (129) of the seats in parliament, UNITA only 31 per cent (70 seats). Although the presidential election result was much closer – MPLA president Jose Eduardo Dos Santos won 49.57 per cent of the votes, with Jonas Savimbi (UNITA) taking 40.07 per cent – it was still a clear and decisive victory for the MPLA.

- However, Savimbi and UNITA refused to accept the result, claiming that there had been fraud, even though the elections had been monitored by 400 UN observers; the leader of the UN team reported that the election had been ‘generally free and fair’. Tragically UNITA, instead of accepting defeat gracefully, renewed the civil war, which was fought with increasing bitterness. By the end of January 1994 the UN reported that there were 3.3 million refugees and that an average of a thousand people a day, mainly civilians, were dying. The UN had too few personnel in Angola to bring the fighting to an end. This time the outside world could not be blamed for the civil war: this was clearly the fault of UNITA. However, many observers blamed the USA for encouraging UNITA:shortly before the Lisbon agreement, President Reagan had officially met Savimbi in the USA, which made him seem like an equal with the MPLA government instead of a rebel leader. At the same time the USA had not officially recognized the MPLA as the legal government of Angola, even after the elections; it was not until May 1993, six months after UNITA had resumed the war, that the USA finally gave recognition to the MPLA government.

- A ceasefire was eventually negotiated in October 1994 and a peace agreement was reached in November. UNITA, which was losing the war by that time, accepted the 1992 election result, and in return was to be allowed to play a part in what would be, in effect, a coalition government. Early in 1995, 7000 UN troops arrived to help enforce the agreement and supervise the transition to peace. But incredibly, Savimbi soon began to break the terms of the agreement; financing his forces with the proceeds from illicit sales of diamonds, he continued the struggle against the government until February 2002, when he was killed in an ambush by government troops. His death changed the situation dramatically Almost immediately the new leaders of UNITA showed a willingness to negotiate. In April 2002 a ceasefire was signed, and the two sides promised to keep the terms of the 1994 agreement. The Angolan National Assembly voted in favour of extending an amnesty to all UNITA members, including fighters and civilians. The whole agreement was to be monitored by the UN. At last, with Savimbi no longer on the scene, there seemed to be a genuine chance for peace and reconstruction in Angola.

- During the 27 years of its existence, Angola had not known real peace, and its development had been severely hampered. It was a potentially prosperous country, rich in oil, diamonds and minerals; the central highlands were fertile – ideal for rearing cattle and raising crops; coffee was a major product. But at the end of the twentieth century the economy was in a mess: inflation was running at 240 per cent, the war was ruinously expensive, and the vast majority of the population was living in poverty, and thousands were on the verge of starvation. Leading politicians faced accusations of corruption on a grand scale. According to the IMF over $4 billion of oil receipts had disappeared from the treasury since 1996. Human Rights Watch reported that UNITA had employed 86 000 child soldiers, and even the government forces had used 3000. The two armies between them had laid some 15 million landmines and many of these still had to be destroyed. It was calculated that about 4 million people (a third of the population) had been forced to leave their homes and were left homeless in 2002, while 1.5 million had been killed.

- Angola’s natural resources enabled the country to recover reasonably quickly economically. An encouraging sign was the signing of a peace deal with the separatist rebels of the Cabinda region. It was a relatively small area with a population of little more than 100 000, but it was important because about 65 per cent of Angola’s oil comes from there. In September 2008 the first national elections for 16 years took place. The ruling MPLA won just over 80 per cent of the votes, while the main opposition party (UNITA) could muster only 10 per cent, giving the MPLA and president José Eduardo dos Santos a two-thirds majority in parliament. By 2010 the president’s popularity was beginning to wane. One of the main criticisms was that he and his family had amassed huge personal fortunes while the country’s recovery and wealth had not percolated down to ordinary people. He survived an assassination attempt in October 2010, and there was an increasing number of massive anti-government demonstrations. By September 2011 the police were using violent methods to disperse demonstrators. However, President dos Santos, now aged 70, appeared to be the comfortable winner in the election of August 2012, and thanks to a change in the constitution, he seemed set to stay in power until 2022.

Genocide In Burundi And Rwanda

The Belgians left these two small states, like the Congo, completely unprepared for independence. In both states there was an explosive mixture of two tribes – the Tutsi and the Hutu. They spoke the same language and looked very much alike, and although the Hutu were in a majority, the Tutsi were the elite ruling group, and they followed different occupations: the Tutsi raised cattle (the word ‘Tutsi’ actually means ‘rich in cattle’), whereas the Hutu were mainly farmers growing bananas and other crops (the word ‘Hutu’ means ‘servant)’. There was continuous tension and skirmishing between the two tribes right from independence day in 1962.

(a) Burundi

- There was a mass rising of Hutus against the ruling Tutsi in 1972; this was savagely put down, and over 100 000 Hutu were killed, along with many Tutsi. Some 200 000 Tutsi fled into Tanzania. In 1988 Hutu soldiers in the Burundi army massacred thousands of Tutsi. In 1993 the country held its first democratic elections and for the first time a Hutu president was chosen. Tutsi soldiers soon murdered the new president, in October 1993, but other members of the Hutu government were able to escape. As Hutu carried out reprisal killings against Tutsi, massacre followed massacre; around 50 000 Tutsi were killed and the country disintegrated into chaos. Eventually the army imposed a power-sharing agreement: the prime minister was to be a Tutsi, the president a Hutu, but most of the power was concentrated in the hands of the Tutsi prime minister.

- Fighting continued into 1996, and the Organization of African Unity, which sent a peacekeeping force (the first time it had ever taken such action), was unable to prevent the continuing massacres and ethnic cleansing. The economy was in ruins, agricultural production was seriously reduced because much of the rural population had fled, and the government seemed to have no ideas about how to end the war. The outside world and the great powers showed little concern – their interests were not involved or threatened – and the conflict in Burundi was not given much coverage in the world’s media. In July 1996, the army overthrew the divided government, and Major Pierre Buyoya (a Tutsi moderate) declared himself president. He claimed that this was not a normal coup – the army had seized power in order to save lives. He had the utmost difficulty in pacifying the country; several former African presidents, including Julius Nyerere of Tanzania and Nelson Mandela of South Africa, attempted to mediate. The problem was that there were about 20 different warring groups, and it was difficult to get representatives of them all together at the same time. In October 2001 an agreement was reached at Arusha (Tanzania), with the help of Mandela. There was to be a three-year transitional period; during the first half of this, Buyoya would continue as president with a Hutu vice-president; after this, a Hutu would become president with a Tutsi vice-president. There was to be an international peacekeeping force and restrictions were to be lifted on political activity. However, not all the rebel groups had signed the Arusha agreement, and fighting continued, in spite of the arrival of South African peacekeepers.

- Prospects for peace brightened in December 2002 when the main Hutu rebel party at last signed a ceasefire with the government. President Buyoya kept his side of the Arusha agreement, handing over the presidency to Domitien Ndayizeye, a Hutu (April 2003). The new president was soon able to reach a power-sharing agreement with the remaining Hutu rebel group, but the peace remained fragile. Elections for parliament in 2005 resulted in a series of victories for the ruling party, and its leader, Pierre Nkurunziza, was chosen as the next president. One of the younger generation of Hutu leaders, he described himself as a born-again Christian and was committed to restoring peace and harmony among all Burundians. He also aimed to revive the economy and develop social policy. His first achievement was to reach a ceasefire with the last of the rebel militias (2006). New policies were introduced to safeguard the rights of women and children and to provide free education for primary-school children. He was also keen to keep in touch with ordinary people, and spent a lot of time in the countryside, meeting and talking with villagers. He received several international honours including a UN peace award, and in August 2009 he was presented with the ‘Model Leader for a New Africa Award’ by the African Forum on Religion and Government, the first African president to be so honoured. In August 2010 President Nkurunziza was elected for a second five-year term.

(b) Rwanda

- Tribal warfare began in 1959 before independence, and reached its first big climax in 1963, when the Hutu, fearing a Tutsi invasion from Burundi, massacred thousands of Rwandan Tutsi and overthrew the Tutsi government. In 1990 fighting broke out between the rebel Tutsi-dominated Rwandese Patriotic Front (Front Patriotique Rwandais – FPR), which was based over the border in Uganda, and the official Rwandan army (Hutu-dominated). This lasted off and on until 1993 when the UN helped to negotiate a peace settlement at Arusha in Tanzania, between the Rwandan government (Hutu) and the FPR (Tutsi): there was to be a more broadly-based government, which would include the FPR; 2500 UN troops were sent to monitor the transition to peace (October 1993).

- For a few months all seemed to be going well, and then disaster struck. The more extreme Hutu were bitterly opposed to the Arusha peace plan, and shocked by the murder of the Hutu president of Burundi. Extremist Hutu, who had formed their own militia (the Interahamwe), decided to act. The aircraft bringing the moderate Hutu President Habyarimana of Rwanda and the Burundian president back from talks in Tanzania was brought down by a missile, apparently fired by extremist Hutu as it approached Kigali (the capital of Rwanda), killing both presidents (April 1994). With the president dead, nobody was sure who was giving the orders, and this gave the Interahamwe the cover they needed to launch a campaign of genocide. The most horrifying tribal slaughter followed; Hutu murdered all Tutsi they could lay hands on, including women and children. A favourite technique was to persuade Tutsi to take sanctuary in churches and then destroy the church buildings and the sheltering Tutsi. Even nuns and clergy were caught up in the massacre. Altogether about 800 000 Tutsi and moderate Hutu who tried to help their neighbours were brutally murdered in what was clearly a deliberate and carefully planned attempt to wipe out the entire Tutsi population of Rwanda, and it was backed by the Hutu government of Rwanda.

- The Tutsi FPR responded by taking up the fight again and marching on the capital; UN observers reported that the streets of Kigali were literally running with blood and the corpses were piled high. The small UN force was not equipped to deal with violence on this scale, and it soon withdrew. The civil war and the genocide continued through into June; in addition to those killed, about a million Tutsi refugees had fled into neighbouring Tanzania and Zaire.

- Meanwhile the rest of the world, though outraged and horrified by the scale of the genocide, did nothing to stop it. Historian Linda Melvern has shown how the warning signs of what was to come were ignored by all those who might have prevented the genocide. She claims that Belgium and France both knew what was being planned; as early as the spring of 1992, the Belgian ambassador told his government that extremist Hutus were ‘planning the extermination of the Tutsi of Rwanda once and for all, and to crush the internal Hutu opposition’. The French continued to supply the Hutu with arms throughout the genocide;US president Clinton knew precisely what was happening, but after the humiliation of the US intervention in Somalia in 1992, he was determined not to get involved. Linda Melvern is highly critical of the UN; she points out that UN secretary-general Boutros-Ghali knew Rwanda well and was aware of the situation, but being pro-Hutu, refused to allow arms inspections and avoided sending sufficient UN forces to deal with the problem. On the other hand, it was not just the West and the UN that turned a blind eye to the tragedy in Rwanda; the Organization of African Unity did not even condemn the genocide, let alone try to prevent it; nor did any other African states take any action or issue public condemnation. Arguably African attention was focused on the new democracy in South Africa rather than on halting the genocide in Rwanda.

- By September the FPR were beginning to get the upper hand: the Hutu government was driven out and a Tutsi FPR government was set up in Kigali. But progress to peace was slow; by the end of 1996 this new government was still beginning to make its authority felt over the whole country, and refugees started to return. Eventually a power-sharing arrangement was reached, and a moderate Hutu, Pasteur Bizimungu, became president with Paul Kagame, a Tutsi, as his vice-president. This was an important concession by the Tutsi as they tried to deflect accusations of a resurgent Tutsi elitism, though in fact Kagame was the real policy decider. However, in 2000 when Bizimungu began to criticize parts of Kagame’s programme, he was removed from the presidency and Kagame took over. Bizimunbu immediately founded an opposition party but the Kagame government banned it.

- One of the problems facing the government was that jails were overflowing with well over 100 000 prisoners awaiting trial for involvement in the 1994 genocide. There were simply too many for the courts to deal with. In January 2003, Kagame ordered the release of around 40 000 prisoners, though it was made clear that they would face trial eventually. This caused consternation among many survivors of the massacres, who were horrified at the prospect of coming face to face with the people who had murdered their relatives.

- A new constitution was introduced in 2003 providing for a president and a two-chamber parliament and established a balance of political power between Hutu and Tutsi – no party can hold more than half the seats in parliament. It also outlawed the incitement of ethnic hatred in the hope of avoiding a repeat of the genocide. In the first national elections since 1994, President Kagame won an overwhelming victory, taking 95 per cent of the votes (August 2003). However, observers reported that there were ‘malpractices’ in some areas, and two of the main opposition parties were banned. But at least Rwanda seemed to be enjoying a period of relative calm. In February 2004, the government introduced a new reconciliation policy: people who admitted their guilt and asked for forgiveness before 15 March 2004 would be released (except those accused of organizing the genocide). It was hoped that this, like the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission, would help Rwandans to come to terms with the traumas of the past and move forward into a period of peace and harmony.

- Certainly economic and social conditions improved during Kagame’s presidency. He succeeded in reducing the amount of corruption and crime; between 2000 and 2008 per capita income doubled; almost half the country’s children were receiving a full primary education, compared with 20 per cent before Kagame came to power; and there was a marked increase in life expectancy. Rwandans infected with AIDS could now receive antiretroviral drugs in health centres across the country. Exports of tea and coffee began to increase, and tourism became an important source of revenue, especially the safari parks. In 2009 Rwanda was accepted as a member of the British Commonwealth of Nations; this was an attempt to distance the country from its Belgian past. President Kagame was decisively re-elected for a further term in August 2010, although doubts were expressed by observers about how free the elections really were. During the election campaign, several opposition supporters and journalists were killed and press freedom was limited. The UN, the European Union and the USA all expressed concerns about these developments.

Apartheid And Black Majority Rule In South Africa

(a) The formation of the Union of South Africa

South Africa has had a complicated history. The first Europeans to settle there permanently were members of the Dutch East India Company who founded a colony at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652. It remained a Dutch colony until 1795, and during that time, the Dutch, who were known as Afrikaners or Boers (a word meaning ‘farmers’), took land away from the native Africans and forced them to work as labourers, treating them as little better than slaves. They also brought more labourers in from Asia, Mozambique and Madagascar.

In 1795 the Cape was captured by the British during the French Revolutionary Wars, and the 1814 peace settlement decided that it should remain British. Many British settlers went out to Cape Colony. The Dutch settlers became restless under British rule, especially when the British government made all slaves free throughout the British Empire (1838). The Boer farmers felt that this threatened their livelihood, and many of them decided to leave Cape Colony. They moved northwards (in what became known as ‘the Great Trek’) and set up their own independent republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State (1835–40). Some also moved into the area east of Cape Colony known as Natal. In the Boer War (1899–1902) the British defeated the Transvaal and the Orange Free State, and in 1910 they joined up with Cape Colony and Natal to form the Union of South Africa.

The population of the new state was mixed:

Approximately

70 per cent were black Africans, known as Bantus;

18 per cent were whites of European origin; of these about 60 per cent were Dutch, the rest British;

9 per cent were of mixed race, known as ‘coloureds’;

3 per cent were Asians.

Although they made up the vast majority of the population, black Africans suffered even worse discrimination than black people in the USA.

- The whites dominated politics and the economic life of the new state, and, with only a few exceptions, blacks were not allowed to vote.

- Black people had to do most of the manual work in factories, in the gold mines and on farms; the men mostly lived in barracks accommodation away from their wives and children. Black people generally were expected to live in areas reserved for them away from white residential areas. These reserved areas made up only about 7 per cent of the total area of South Africa and were not large enough to enable the Africans to produce sufficient food for themselves and to pay all their taxes. Black Africans were forbidden to buy land outside the reserves.

- The government controlled the movement of blacks by a system of pass laws. For example, a black person could not live in a town unless he had a pass showing that he was working in a white-owned business. An African could not leave the farm where he worked without a pass from his employer; nor could he get a new job unless his previous employer signed him out officially; many workers were forced to stay in difficult working conditions, even under abusive employers.

- Living and working conditions for blacks were primitive; for example, in the gold-mining industry, Africans had to live in single-sex compounds with sometimes as many as 90 men sharing a dormitory.

- By a law of 1911, black workers were forbidden to strike and were barred from holding skilled jobs.

(b) Dr Malan introduces apartheid

After the Second World War there were important changes in the way black Africans were treated. Under Prime Minister Malan (1948–54), a new policy called apartheid (separateness) was introduced. This tightened up control over blacks still further. Why was apartheid introduced?

- When India and Pakistan were given independence in 1947, white South Africans became alarmed at the growing racial equality within the Commonwealth, and they were determined to preserve their supremacy.

- Most of the whites, especially those of Dutch origin, were against racial equality, but the most extreme were the Afrikaner Nationalist Party led by Dr Malan. They claimed that whites were a master race, and that non-whites were inferior beings. The Dutch Reformed Church (the official state church of South Africa) supported this view and quoted passages from the Bible which, they claimed, proved their theory. This was very much out of line with the rest of the Christian churches, which believe in racial equality. The Broederbond was a secret Afrikaner organization which worked to protect and preserve Afrikaner power.

- The Nationalists won the 1948 elections with promises to rescue the whites from the ‘black menace’ and to preserve the racial purity of the whites. This would help to ensure continued white supremacy.

(c) Apartheid developed further

Apartheid was continued and developed further by the prime ministers who followed Malan: Strijdom (1954–8), Verwoerd (1958–66) and Vorster (1966–78).

The main features of apartheid

- There was complete separation of blacks and whites as far as possible at all levels. In country areas blacks had to live in special reserves; in urban areas they had separate townships built at suitable distances from the white residential areas. If an existing black township was thought to be too close to a ‘white’ area, the whole community was uprooted and ‘re-grouped’ somewhere else to make separation as complete as possible. There were separate buses, coaches, trains, cafés, toilets, park benches, hospitals, beaches, picnic areas, sports and even churches. Black children went to separate schools and were given a much inferior education. But there was a flaw in the system: complete separation was impossible because over half the non-white population worked in white-owned mines, factories and other businesses. The economy would have collapsed if all non-whites had been moved to reserves. In addition, virtually every white household had at least two African servants.

- Every person was given a racial classification and an identity card. There were strict pass laws which meant that black Africans had to stay in their reserves or in their townships unless they were travelling to a white area to work, in which case they would be issued with passes. Otherwise all travelling was forbidden without police permission.

- Marriage and sexual relations between whites and non-whites were forbidden; this was to preserve the purity of the white race. Police spied shamelessly on anybody suspected of breaking the rules.

- The Bantu Self-Government Act (1959) set up seven regions called Bantustans, based on the original African reserves. It was claimed that they would eventually move towards self-government. In 1969 it was announced that the first Bantustan, the Transkei, had become ‘independent’. However, the outside world dismissed this with contempt since the South African government continued to control the Transkei’s economy and foreign affairs. The whole policy was criticized because the Bantustan areas covered only about 13 per cent of the country’s total area; over 8 million black people were crammed into these relatively small areas, which were vastly overcrowded and unable to support the black populations adequately. They became very little better than rural slums, but the government ignored the protests and continued its policy; by 1980 two more African ‘homelands’, Bophuthatswana and Venda, had received ‘independence’.

- Africans lost all political rights, and their representation in parliament, which had been by white MPs, was abolished.

(d) Opposition to apartheid

1. Inside South Africa

Inside South Africa, opposition to the system was difficult. Anyone who objected – including whites – or broke the apartheid laws, was accused of being a communist and was severely punished under the Suppression of Communism Act. Africans were forbidden to strike, and their political party, the African National Congress (ANC), was helpless. In spite of this, protests did take place.

- Chief Albert Luthuli, the ANC leader, organized a protest campaign in which black Africans stopped work on certain days. In 1952 Africans attempted a systematic breach of the laws by entering shops and other places reserved for whites. Over 8000 blacks were arrested and many were flogged. Luthuli was deprived of his chieftaincy and put in jail for a time, and the campaign was called off.

- In 1955 the ANC formed a coalition with Asian and coloured groups, and at a massive open-air meeting at Kliptown (near Johannesburg), they just had time to announce a freedom charter before police broke up the crowd. The charter soon became the main ANC programme. It began by declaring: ‘South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and no government can claim authority unless it is based on the will of the people.’ It went on to demand:

- equality before the law;

- freedom of assembly, movement, speech, religion and the press;

- the right to vote;

- the right to work, with equal pay for equal work;

- a 40-hour working week, a minimum wage and unemployment benefits;

- free medical care;

- free, compulsory and equal education.

- Church leaders and missionaries, both black and white, spoke out against apartheid. They included people like Trevor Huddleston, a British missionary who had been working in South Africa since 1943.

- Later the ANC organized other protests, including the 1957 bus boycott: instead of paying a fare increase on the bus route from their township to Johannesburg ten miles away, thousands of Africans walked to work and back for three months until fares were reduced.

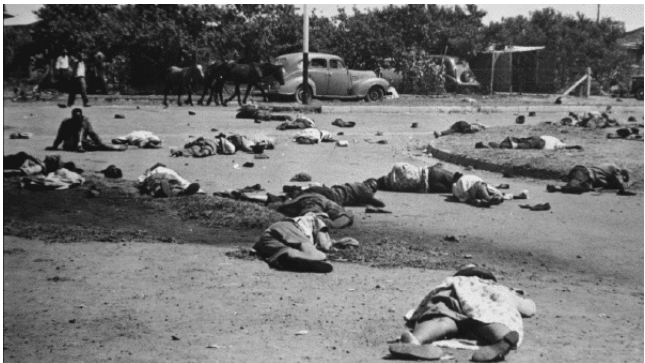

- Protests reached a climax in 1960 when a huge demonstration took place against the pass laws at Sharpeville, an African township near Johannesburg. Police fired on the crowd, killing 67 Africans and wounding many more (see Illus. 25.1). After this, 15 000 Africans were arrested and hundreds of people were beaten by police. This was an important turning point in the campaign: until then most of the protests had been non-violent; but this brutal treatment by the authorities convinced many black leaders that violence could only be met with violence.

- A small action group of the ANC, known as Umkhonto we Sizwe (Spear of the Nation), or MK, was launched; Nelson Mandela was a prominent member. They organized a campaign of sabotaging strategic targets: in 1961 there was a spate of bomb attacks in Johannesburg, Port Elizabeth and Durban. But the police soon clamped down, arresting most of the black leaders, including Mandela, who was sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island. Chief Luthuli still persevered with non-violent protests, and after publishing his moving autobiography Let My People Go, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He was killed in 1967, the authorities claiming that he had deliberately stepped in front of a train.

- Discontent and protest increased again in the 1970s because the wages of Africans failed to keep pace with inflation. In 1976, when the Transvaal authorities announced that Afrikaans (the language spoken by whites of Dutch descent) was to be used in black African schools, massive demonstrations took place at Soweto, a black township near Johannesburg. Although there were many children and young people in the crowd, police opened fire, killing at least 200 black Africans. This time the protests did not die down; they spread over the whole country. Again the government responded with brutality: over the next six months a further 500 Africans were killed; among the victims was Steve Biko, a young African leader who had been urging people to be proud of their blackness. He was beaten to death by police (1976).

Illustration 25.1 Bodies litter the ground after the Sharpeville massacre, South Africa, 1960

2. Outside South Africa

2. Outside South Africa

Outside South Africa there was opposition to apartheid from the rest of the Commonwealth. Early in 1960 the British Conservative prime minister, Harold Macmillan, had the courage to speak out against it in Cape Town; he spoke about the growing strength of African nationalism: ‘the wind of change is blowing through the continent … our national policies must take account of it’. His warnings were ignored, and shortly afterwards, the world was horrified by the Sharpeville massacre. At the 1961 Commonwealth Conference, criticism of South Africa was intense, and many thought the country would be expelled. In the end Verwoerd withdrew South Africa’s application for continued membership (in 1960 it had become a republic instead of a dominion, thereby severing the connection with the British crown; because of this the government had had to apply for readmission to the Commonwealth), and it ceased to be a member of the Commonwealth.

3. The UN and OAU

The United Nations and the Organization of African Unity condemned apartheid and were particularly critical of the continued South African occupation of South West Africa (see above, Section 25.6(b)). The UN voted to place an economic boycott on South Africa (1962), but this proved useless because not all member states supported it. Britain, the USA, France, West Germany and Italy condemned apartheid in public, but continued to trade with South Africa. Among other things, they sold South Africa massive arms supplies, apparently hoping that it would prove to be a bastion against the spread of communism in Africa. Consequently Verwoerd (until his assassination in 1966) and his successor Vorster (1966–78) were able to ignore the protests from the outside world until well into the 1970s.

(e) The end of apartheid

The system of apartheid continued without any concessions being made to black people, until 1980.

1. P. W. Botha

The new prime minister, P. W. Botha (elected 1979), realized that all was not well with the system. He decided that he must reform apartheid, dropping some of the most unpopular aspects in an attempt to preserve white control. What caused this change?

- Criticism from abroad (from the Commonwealth, the United Nations and the Organization of African Unity) gradually gathered momentum. External pressures became much greater in 1975 when the white-ruled Portuguese colonies of Angola and Mozambique achieved independence after a long struggle (see Section 24.6(d)). The African takeover of Zimbabwe (1980) removed the last of the white-ruled states which had been sympathetic to the South African government and apartheid. Now South Africa was surrounded by hostile black states, and many Africans in these new states had sworn never to rest until their fellow-Africans in South Africa had been liberated.

- There were economic problems – South Africa was hit by recession in the late 1970s, and many white people were worse off. Whites began to emigrate in large numbers, but the black population was increasing. In 1980 whites made up only 16 per cent of the population, whereas between the two world wars they had formed 21 per cent.

- The African homelands were a failure: they were poverty-stricken, their rulers were corrupt and no foreign government recognized them as genuinely independent states.

- The USA, which was treating its own black people better during the 1970s, began to criticize the South African government’s racist policy.

In a speech in September 1979 which astonished many of his Nationalist supporters, the newly elected Prime Minister Botha said:

A revolution in South Africa is no longer just a remote possibility. Either we adapt or we perish. White domination and legally enforced apartheid are a recipe for permanent conflict.

He went on to suggest that the black homelands must be made viable and that unnecessary discrimination must be abolished. Gradually he introduced some important changes which he hoped would be enough to silence the critics both inside and outside South Africa.

- Blacks were allowed to join trade unions and to go on strike (1979).

- Blacks were allowed to elect their own local township councils (but not to vote in national elections) (1981).

- A new constitution was introduced, setting up two new houses of parliament, one for coloureds and one for Asians (but not for Africans). The new system was weighted so that the whites kept overall control. It came into force in 1984.

- Sexual relations and marriage were allowed between people of different races (1985).

- The hated pass laws for non-whites were abolished (1986).

This was as far as Botha was prepared to go. He would not even consider the ANC’s main demands (the right to vote and to play a full part in ruling the country). Far from being won over by these concessions, black Africans were incensed that the new constitution made no provision for them, and were determined to settle for nothing less than full political rights.

Violence escalated, with both sides guilty of excesses. The ANC used the ‘necklace’, a tyre placed round the victim’s neck and set on fire, to murder black councillors and black police, who were regarded as collaborators with apartheid. On the 25th anniversary of Sharpeville, police opened fire on a procession of black mourners going to a funeral near Uitenhage (Port Elizabeth), killing over forty people (March 1985). In July a state of emergency was declared in the worst affected areas, and it was extended to the whole country in June 1986. This gave the police the power to arrest people without warrants, and freedom from all criminal proceedings; thousands of people were arrested, and newspapers, radio and TV were banned from reporting demonstrations and strikes.

However, as so often happens when an authoritarian regime tries to reform itself, it proved impossible to stop the process of change (the same happened in the USSR when Gorbachev tried to reform communism). By the late 1980s international pressure on South Africa was having more effect, and internal attitudes had changed.

- In August 1986 the Commonwealth (except Britain) agreed on a strong package of sanctions (no further loans, no sales of oil, computer equipment or nuclear goods to South Africa, and no cultural and scientific contacts). British prime minister Margaret Thatcher would commit Britain only to a voluntary ban on investment in South Africa. Her argument was that severe economic sanctions would worsen the plight of black Africans, who would be thrown out of their jobs. This caused the rest of the Commonwealth to feel bitter against Britain; Rajiv Gandhi, the Indian prime minister, accused Mrs Thatcher of ‘compromising on basic principles and values for economic ends’.

- In September 1986 the USA joined the fray when Congress voted (over President Reagan’s veto) to stop American loans to South Africa, to cut air links and to ban imports of iron, steel, coal, textiles and uranium from South Africa.

- The black population was no longer just a mass of uneducated and unskilled labourers; there was a steadily growing number of well-educated, professional, middle-class black people, some of them holding important positions, like Desmond Tutu, who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 and became Anglican archbishop of Cape Town in 1986.

- The Dutch Reformed Church, which had once supported apartheid, now condemned it as incompatible with Christianity. A majority of white South Africans now recognized that it was difficult to defend the total exclusion of blacks from the country’s political life. So although they were nervous about what might happen, they became resigned to the idea of black majority rule at some time in the future. White moderates were therefore prepared to make the best of the situation and get the best deal possible.

2. F. W. de Klerk

The new president, F. W. de Klerk (elected 1989), had a reputation for caution, but privately he had decided that apartheid would have to go completely, and he accepted that black majority rule must come eventually. The problem was how to achieve it without further violence and possible civil war. With great courage and determination, and in the face of bitter opposition from right-wing Afrikaner groups, de Klerk gradually moved the country towards black majority rule.

- Nelson Mandela was released after 27 years in jail (1990) and became leader of the ANC, which was made legal.

- Most of the remaining apartheid laws were dropped.

- Namibia, the neighbouring territory ruled by South Africa since 1919, was given independence under a black government (1990).

- Talks began in 1991 between the government and the ANC to work out a new constitution which would allow blacks full political rights.

Meanwhile the ANC was doing its best to present itself as a moderate party which had no plans for wholesale nationalization, and to reassure whites that they would be safe and happy under black rule. Nelson Mandela condemned violence and called for reconciliation between blacks and whites. The negotiations were long and difficult; de Klerk had to face right-wing opposition from his own National Party and from various extreme, white racial-ist groups who claimed that he had betrayed them. The ANC was involved in a power struggle with another black party, the Natal-based Zulu Inkatha Freedom Party led by Chief Buthelezi.

3. Transition to black majority rule

In the spring of 1993 the talks were successful and a power-sharing scheme was worked out to carry through the transition to black majority rule. A general election was held and the ANC won almost two-thirds of the votes. As had been agreed, a coalition government of the ANC, National Party and Inkatha took office, with Nelson Mandela as the first black president of South Africa, two vice-presidents, one black and one white (Thabo Mbeki and F. W. de Klerk), and Chief Buthelezi as Home Affairs Minister (May 1994). A right-wing Afrikaner group, led by Eugene Terreblanche, continued to oppose the new democracy, vowing to provoke civil war, but in the end it came to nothing. Although there had been violence and bloodshed, it was a remarkable achievement, for which both de Klerk and Mandela deserve the credit, that South Africa was able to move from apartheid to black majority rule without civil war.

(f) Mandela and Mbeki

- The government faced daunting problems and was expected to deliver on the promises in the ANC programme, especially to improve conditions for the black population. Plans were put into operation to raise their general standard of living – in education, housing, health care, water and power supplies and sanitation. But the scale of the problem was so vast that it would be many years before standards would show improvement for everybody. In May 1996 a new constitution was agreed, to come into operation after the elections of 1999, which would not allow minority parties to take part in the government. When this was revealed (May 1996), the Nationalists immediately announced that they would withdraw from the government to a ‘dynamic but responsible opposition’. As the country moved towards the millennium, the main problems facing the president were how to maintain sound financial and economic policies, and how to attract foreign aid and investment; potential investors were hesitant, awaiting future developments.

- One of Mandela’s most successful initiatives was the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which looked into human rights abuses during the apartheid regime. Assisted by Archbishop Desmond Tutu, the commission’s approach was not one of taking revenge, but of granting amnesties; people were encouraged to talk frankly, and to acknowledge their crimes and ask for forgiveness. This was one of the most admirable things about Mandela, that although he had been kept in prison under the apartheid regime for 27 years, he still believed in forgiveness and reconciliation. The president decided not to stand for re-election in 1999 – he was almost 81 years old; he retired with his reputation high, almost universally admired for his statesmanship and restraint.

- Thabo Mbeki, who became ANC leader and president on Mandela’s retirement, had a difficult job to follow such a charismatic leader. After winning the 1999 elections, Mbeki and the ANC had to deal with mounting problems: the crime rate soared, trade unions called strikes in protest against job losses, poor working conditions and the increasing rate of privatization. The economic growth rate was slowing down: in 2001 it was only 1.5 per cent compared with 3.1 in 2000. The government came under special criticism for its handling of the AIDS epidemic. Mbeki was slow to recognize that there really was a crisis and claimed that AIDS was not necessarily linked to HIV; he refused to declare a state of emergency, as opposition parties and trade unions demanded. This would have enabled South Africa to obtain cheaper medicines, but the government seemed unwilling to spend large amounts of cash on the necessary drugs. There was uproar in October 2001 when a report claimed that AIDS was now the main cause of death in South Africa, and that if the trend continued, at least 5 million people would have died from it by 2010.

- As the 2004 elections approached, there were many positive signs in the new South Africa. Government policies were beginning to show results: 70 per cent of black households had electricity, the number of people with access to pure water had increased by 9 million since 1994, and about 2000 new houses for poor people had been built. Education was free and compulsory and many black people said that they felt they now had dignity, instead of being treated like animals, as they had been under apartheid. The economic situation appeared brighter: South Africa was diversifying its exports instead of relying on gold and there was a growing tourist industry; the budget deficit had fallen sharply and inflation was down to 4 per cent. The main problems were still AIDS – it was reported that in 2005 South Africa was the country with the most HIV positive people in the world, 6.5 million; high unemployment levels and the high crime rate. However, in the election of April 2004, Mbeki was re-elected for a second and final five-year term as president and his ANC won a landslide victory, taking around two-thirds of the votes cast.

- During Mbeki’s second term it was the problems rather than the progress that gained most of the publicity. There was an influx of migrants and refugees, mainly from Zimbabwe, but also from Rwanda, the Congo, Somalia and Ethiopia. With unemployment already high and housing in short supply, this has caused competition for jobs and living accommodation, especially in the shanty towns that surround most large cities. In May 2008 there were serious protest riots directed against immigrants, and at least 80 people were killed. The more left-wing ANC supporters felt that there had been too little progress in the redistribution of wealth. In May 2009 South Africa’s unemployment rate had reached 25 per cent and those out of work were forced to live on less than US$1.25 a day. Mbeki’s second term was also marred by a feud with his vice-president Jacob Zuma. In 2005 Mbeke sacked him after Zuma was accused of corruption, including fraud and money-laundering. In December 2007 Zuma, still a very popular figure, defeated Mbeke in the election for president of the ANC. When Zuma was acquitted on the corruption charges, the ANC National Executive Committee voted that Mbeke was no longer fit to lead the country, the implication being that the charges against Zuma had been trumped up in order to get him removed. Mbeke immediately resigned and in May 2009 Zuma was elected president. He was firmly on the left-wing of the ANC and had once been a member of the South African Communist Party. Now he could rely on solid support from the trade unions and the communists. His programme included a pledge to fight poverty and narrow the poverty gap, given that South Africa was tenth in the world list of countries with the widest gap between rich and poor.

- The president suffered a setback in August 2012 when police shot and killed 34 striking platinum miners at the Marikana mine, near Johannesburg. Poorly paid and working in difficult conditions, the miners were demanding wage increases from the mine-owners, a British company called Lonmin. To make matters worse, 270 miners were arrested and charged with the murder of their colleagues, on the grounds that their behaviour had caused the police action. A wave of outrage followed and President Zuma came under severe criticism for his handling of the crisis. Although the charges were later dropped, critics claimed that he was an ineffective leader, more interested in protecting the industry rather than helping the poverty-stricken miners and working to narrow the poverty gap. In December 2012 he was re-elected leader of the ANC for another five years. However, many observers see his continuing presence as the party’s Achilles heel. According to the Guardian (18 December 2012), Zuma is ‘a man steeped in corruption and personal scandal’.

Socialism And Civil War In Ethiopia

(a) Haile Selassie

- Ethiopia (Abyssinia) was an independent state, ruled since 1930 by the Emperor Haile Selassie. In 1935 Mussolini’s forces attacked and occupied the country, forcing the Emperor into exile. The Italians joined Ethiopia to their neighbouring colonies of Eritrea and Somaliland, calling them Italian East Africa. In 1941, with British help, Haile Selassie was able to defeat the weak Italian forces and return to his capital, Addis Ababa. The wily emperor scored a great success in 1952 when he persuaded the UN and the USA to allow him to take over Eritrea, giving his landlocked country access to the sea. However, this was to be a source of conflict for many years, since Eritrean nationalists bitterly resented the loss of their country’s independence.

- By 1960 many people were growing impatient with Haile Selassie’s rule, believing that more could have been done politically, socially and economically to modernize the country. Rebellions broke out in Eritrea and in the Ogaden region of Ethiopia, where many of the population were Somali nationalists who were keen for their territories to join Somalia (which had become independent in 1960). Haile Selassie hung on to power, without introducing any radical changes, into the 1970s. Fuelled by poverty, drought and famine, unrest finally came to a head in 1974, when some sections of the army mutinied. The leaders formed themselves into the Co-ordinating Committee of the Armed Forces and Police (known as the Derg for short), whose chairman was Major Mengistu. In September 1974, the Derg deposed the 83-year-old emperor, who was later murdered, and set itself up as the new government. Mengistu gained complete control and remained head of state until 1991.

(b) Major Mengistu and the Derg

Mengistu and the Derg gave Ethiopia 16 years of government based on Marxist principles. Most of the land, industry, trade, banking and finance were taken over by the state. Opponents were usually executed. The USSR saw the arrival of Mengistu as an excellent chance to gain influence in that part of Africa, and they provided armaments and training for Mengistu’s army. Unfortunately the regime’s agricultural policy ran into the same problems as Stalin’s collectivization in the USSR; in 1984 and 1985 there were terrible famines, and it was only prompt action by other states, rushing in emergency food supplies, which averted disaster. Mengistu’s main problem was the civil war, which dragged on throughout his period in power and swallowed up his scarce resources. In spite of the help from the USSR, he was fighting a losing battle against the Eritrean People’s Liberation Front, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front and the Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). By 1989 the government had lost control of Eritrea and Tigray, and Mengistu admitted that his socialist policies had failed; Marxism–Leninism was to be abandoned. The USSR deserted him; in May 1991, with rebel forces closing in on Addis Ababa, Mengistu fled to Zimbabwe and the EPRDF took power.

(c) The Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF)

- The new government, while maintaining some elements of socialism (especially state control of important resources), promised democracy and less centralization. The leader, Meles Zenawi, who was a Tigrayan, announced the introduction of a voluntary federation for the various nationalities; this meant that ethnic groups could leave Ethiopia if they chose, and it prepared the way for Eritrea to declare its independence in May 1993. This was one less problem for the regime to deal with, but there were many others. Most serious was the state of the economy, and yet another dreadful famine in 1994. In 1998 war broke out between Ethiopia and Eritrea over frontier disputes. Even the weather was unco-operative: in the spring of 2000 the rains failed for the third year in succession, and another famine threatened. Although a peace settlement with Eritrea was signed in December 2000, tensions remained high.

- Events in 2001 suggested that Ethiopia might have turned the corner, at least economically. Prime Minister Zenawi and his EPRDF, who had easily won the national elections in May 2000, went on to register another landslide victory in the local elections in 2001. The economy grew by 6.5 per cent, the rains arrived on time and there was a good harvest. The World Bank helped by cancelling almost 70 per cent of Ethiopia’s debt. Zenawi won the 2005 elections, though there were allegations of fraud followed by riots and protest demonstrations in which at least 200 people were killed. The opposition accused the police of massacring protesters, while the government blamed one of the main opposition parties, the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (CUD), for organizing the protests. In fact the majority of foreign observers declared that the elections were basically free and fair. With Zenawi in charge for the next five years, economic growth continued, but at the end of 2006 Ethiopia became involved in war with neighbouring Somalia. In the south of Somalia, bordering on Ethiopia, Islamist groups were fighting against the National Transitional Federal Government of Somalia, which was supported by the USA (see Section 25.13(b)). It was suspected that these Islamist groups had links with al-Qaeda, and Ethiopia had already allowed the USA to station military advisers at Camp Hurso, where they had spent a year training the Ethiopian army. In December 2006 the Ethiopians took the offensive, forced the Islamists to retreat and occupied the areas formerly under Islamist control. They pulled out in January 2009, leaving behind a small African Union force and a small detachment of the Somali army. But they were not strong enough to keep the Islamists at bay, and they soon began to take back control of southern Somalia. Re-elected in 2010 for a further five-year term, Zenawi died in August 2012 aged only 57. His deputy, Hailemariam Desalegn, took over, and was expected to remain prime minister until the next elections, due in 2015. However, there were fears that, since the new prime minister lacked the experience, the prestige and the charisma of Mr Zenawi, the country was in for a difficult few years.

Liberia – A Unique Experiment

(a) Early history

- Liberia has a unique history among African states. It was founded in 1822 by an organization called the American Colonization Society, whose members thought it would be a good idea to settle freed slaves in Africa where, by rights, they ought to have been living in the first place. They persuaded several local chieftains to allow them to start a settlement in West Africa. The initial training of the freed slaves to prepare them for running their own country was carried out by white Americans, led by Jehudi Ashmun. Liberia was given a constitution based on that of the USA, and the capital was named Monrovia after James Monroe, US president from 1817 until 1825. Although the system appeared to be democratic, in practice only the descendants of American freed slaves were allowed to vote. The native Africans in the area were treated as second-class citizens, just as they were in the areas colonized by Europeans. In the late 1920s there was a scandal when the US State Department accused the Liberian government of selling large numbers of these citizens into slavery. The League of Nations carried out an investigation and in 1930 published a report showing that this was indeed the case. There were probably mixed motives: to make money for the poverty-stricken government and to get rid of troublemakers from native tribes in the interior. The president, Charles King, was forced to resign, but a further investigation in 1935, this time by the Anti-Slavery Society, showed that the practice was still going on. One of the investigators was the British novelist, Graham Greene.

- Liberia gained new importance during the Second World War because of its rubber plantations, which were a vital source of natural latex rubber for the Allies. The Americans poured cash into the country and built roads, harbours and an international airport at Monrovia. In 1943, William Tubman of the True Whig Party – the only major political party – was elected president; he was continually re-elected and remained president until his death in 1971, shortly after his election for a seventh term. He presided over a largely peaceful country, which became a member of the UN and a founder member of the Organization of African Unity (1963). But the economy was always precarious; there was little industry and Liberia depended heavily on her exports of rubber and iron ore. Another source of income came from allowing foreign merchant ships to register under the Liberian flag. Shipowners were keen to do this because Liberia’s rules and safety regulations were the most lax in the world and the registration fees among the lowest.

(b) Military dictatorship and civil war

- President Tubman was succeeded by his vice-president, William Tolbert, but during his presidency things began to go badly wrong. There was a fall in the world prices of rubber and iron ore and the ruling elite came under increasing criticism for its corruption. Opposition groups developed and in 1980 the army staged a coup, led by Master Sergeant Samuel Doe. Tolbert was overthrown and executed in public along with his ministers, and Doe became head of state. He promised a new constitution and a return to civilian rule, but was in no hurry to relinquish power. Although elections were held in 1985, Doe made sure that he and his supporters won. His ruthless regime aroused determined opposition and a number of rebel groups emerged; by 1989 Liberia was engaged in a bloody civil war. The rebel armies were poorly disciplined and guilty of indiscriminate shooting and looting. In spite of efforts by neighbouring West African states which intervened in an attempt to bring peace, Doe was captured and killed (1990); but this did not end the war: two of the rebel groups, led by Charles Taylor and Prince Johnson (the man responsible for Doe’s murder), fought each other for control of the country. Altogether this devastating conflict raged on for seven years; new rival factions appeared; at one point Taylor’s forces invaded Sierra Leone which he accused of backing Prince Johnson who controlled the capital, Monrovia. The Organization of African Unity tried to broker talks under the chairmanship of former Zimbabwean president Canaan Banana; but it was not until 1996 that a cease-fire was agreed. Taylor succeeded in winning the support of Nigeria and announced that he wanted to be a conciliator.

- Elections held in 1997 resulted in a decisive victory for Charles Taylor and the National Patriotic Front of Liberia Party. He faced an unenviable task: the country was literally in ruins, its economy was totally disrupted and its peoples were divided. Nor did the situation improve. Taylor soon found himself at odds with much of the outside world: the USA criticized his human rights record and the European Union claimed that he was helping the rebels in Sierra Leone. After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, the USA accused him of harbouring members of al-Qaeda. Taylor denied all these charges and accused the USA of trying to undermine his government. The UN voted to impose a worldwide ban on the trade in Liberian diamonds.

- By the spring of 2002 the country was once again in the grip of civil war as rebel forces in the north launched a campaign to overthrow Taylor. Again the ordinary people suffered appallingly: by the end of the year, 40 000 had fled the country and a further 300 000 were only kept alive by food aid from the UN. In August 2003 the UN Security Council decided to send security forces into Liberia and about a thousand Nigerian troops were airlifted into Monrovia to prevent rebel forces taking it. Taylor resigned and took refuge in Nigeria. All the various factions met and signed a peace agreement. There was to be a two-year transitional period, during which a UN force of 3500 troops from several West African countries would keep the peace. Democratic elections were held in October and November 2005 in which the final run-off was won by Ellen Johnson-Shirleaf, who became Africa’s first female head of state. She had been educated at Harvard, and had worked as an economist for the World Bank.

- In 2006 ex-president Charles Taylor was handed over to an international court at the Hague and charged with crimes against humanity alleged to have been committed in the 1990s when he intervened to support the rebels in the civil war in Sierra Leone. In April 2012 he was found guilty of being responsible for murder, rape, sexual slavery and conscription of child soldiers. He was sentenced to 50 years in prison. Meanwhile in 2011 president Johnson-Shirleaf was a joint winner, along with two other African female politicians from Liberia and Yemen, of the Nobel Peace Prize for their work for the safety of women and for women’s rights. Later in the year she was re-elected president for a second term.

Stability And Chaos In Sierra Leone

(a) Early prosperity and stability

Sierra Leone became independent in 1961 with Sir Milton Margai as leader and with a democratic constitution based on the British model. It was potentially one of the richest states in Africa, with valuable iron-ore deposits and diamonds; later gold was discovered. Sadly, the enlightened and gifted Margai, widely seen as the founding father of Sierra Leone, died in 1964. His brother, Sir Albert Margai, took over as leader, but in the election of 1967, his party (the Sierra Leone People’s Party – SLPP) was defeated by the All-People’s Congress (APC) and its leader Siaka Stevens. In a foretaste of the future, the army removed the new prime minister and installed a military government. This had only been in place for a year when some sections of the army mutinied, imprisoned their officers and restored Stevens and the APC to power. Stevens remained president until his retirement in 1985.

Sierra Leone under Siaka Stevens enjoyed peace and stability, but gradually the situation deteriorated in a number of ways.

- Corruption and mismanagement crept in and the ruling elite lined their own pockets at public expense.

- The deposits of iron ore ran out, and the diamond trade, which should have filled the state treasury, fell into the hands of smugglers, who siphoned off most of the profits.

- As criticism of the government increased, Stevens resorted to dictatorial methods. Many political opponents were executed, and in 1978 all political parties except the APC were banned.

(b) Chaos and catastrophe

- When Stevens retired in 1985 he took care to appoint as his successor another strong man, the Commander-in-Chief of the army, Joseph Momoh. His regime was so blatantly corrupt and his economic policies so disastrous that in 1992 he was overthrown, and replaced by a group calling itself the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC). The new head of state, Captain Valentine Strasser, accused Momoh of bringing the country ‘permanent poverty and a deplorable life’, and promised to restore genuine democracy as soon as possible.

- Unfortunately the country was already moving towards the tragic civil war, which was to last into the next century. A rebel force calling itself the Revolutionary United Front(RUF) was organizing in the south, under the leadership of Foday Sankoh. He had been an army corporal who, according to Peter Penfold (a former British High Commissioner in Sierra Leone), ‘brainwashed his young followers on a diet of coercion, drugs, and unrealistic promises of gold’. His forces had been causing trouble since 1991, but the violence intensified; Sankoh rejected all calls to negotiate, and by the end of 1994 the Strasser government was in difficulties. Early in 1995 there were reports of fierce fighting all over the country, although Freetown (the capital) was still calm. An estimated 900 000 people had been driven from their homes and at least 30 000 had taken refuge in neighbouring Guinea.

- In desperation Strasser offered to hold democratic elections and to sign a truce with the RUF. This produced a lull in the fighting and preparations went ahead for elections to be held in February 1996. However, some sections of the army were unwilling to give up power to a civilian government, and a few days before the election they overthrew Strasser. Nevertheless, voting went ahead, though there was serious violence, especially in Freetown, where 27 people were killed. There were reports of mutinous soldiers firing at civilians as they queued up to vote, and chopping off the hands of some people who had voted. In spite of intimidation, 60 per cent of the electorate voted. The Sierra Leone People’s Party (SLPP) emerged as the largest party and its leader, Ahmad Tejan Kabbah, was elected president. Enormous crowds celebrated in Freetown when the army formally handed over authority to the new president, after 19 years of one-party and military rule. President Kabbah pledged to end violence and corruption and offered to meet RUF leaders. In November 1996 he and Sankoh signed a peace agreement.

- Just as it seemed that peace was about to return, the country was plunged into further chaos when a group of army officers seized power (May 1997), forcing Kabbah to take refuge in Guinea. The new president, Major Johnny Paul Koroma, abolished the constitution and banned political parties. Sierra Leone was suspended from the Commonwealth and the UN imposed economic sanctions until the country returned to democracy. Nigerian forces fighting on behalf of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) drove Koroma’s military regime out and restored Kabbah (March 1998).

- But this was not the end of Sierra Leone’s misery. The RUF resurrected itself and was joined by troops loyal to Koroma. They advanced on Freetown, which they reached in January 1999. Then followed the most appalling events of the entire civil war: in a ten-day period about 7000 people were murdered, thousands more were raped or had their arms and legs hacked off, about a third of the capital was destroyed and tens of thousands were left homeless. Eventually Kabbah and Sankoh signed a peace agreement in Lomé, the capital of Togo (July 1999), providing for a power-sharing system and granting an amnesty for the rebels. This provoked strong criticism from human rights groups in view of the terrible atrocities committed by some of the rebels. The UN Security Council voted to send 6000 troops to Sierra Leone to supervise the implementation of peace. Unbelievably, in May 2000 Sankoh, who had become a member of Kabbah’s cabinet, ordered his rebel troops to march on Freetown and overthrow the Kabbah government. This was prevented by the timely arrival of British troops sent by UK prime minister Tony Blair. In October 2000 this number had to be increased to 20 000, since many of the RUF fighters refused to accept the terms of the settlement and continued to cause havoc. British troops joined the UN forces and played an important part in the final defeat of the rebels. Sankoh was captured and died in prison in 2003. The job of disarmament was slow and difficult, but violence gradually subsided and something approaching calm was restored. In January 2002 the war was officially declared to be over; it was estimated that 50 000 people had been killed during ten years of conflict.

- However, peace was fragile, and the UN kept 17 000 troops in the country, and some of the British contingent stayed in case of renewed violence. In May 2002 President Kabbah was re-elected, winning 70 per cent of the votes. In 2004 it was announced that all rebel troops had been disarmed and the UN opened a war crimes tribunal. But the country’s economy was in ruins, the infrastructure needed rebuilding, and in 2003 the UN rated it as one of the five poorest countries in the world.

- The constitution did not allow President Kabbah to run for a third consecutive term, and his party, the Sierra Leonean People’s Party (SLPP), chose the vice-president, Solomon Berewa, as their candidate in the elections of September 2007. He was unexpectedly defeated by the All People’s Party (APC) candidate, Ernest Bai Koroma. He promised that corruption would not be tolerated and that the country’s resources would be used in the best interests of all citizens. Further work was done to restore the country’s infrastructure and more resources were put into the healthcare system. In April 2010 a new free health-care system was introduced for pregnant women, mothers and babies, and children under 5. In 2008, after an aircraft carrying around 700 kg of cocaine was stopped at Freetown airport, President Koroma took action against the increasing number of drug cartels, many of them from Colombia, which had started to use Sierra Leone as a base from which to ship drugs to Europe. The minister for transport was suspended and stricter punishments and longer gaol sentences were introduced for offenders. As the 2012 elections approached, there was still a long way to go before Sierra Leone came anywhere near fulfilling its potential.

|

50 videos|67 docs|30 tests

|

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|