Sangam Age: Trade Guilds and Urban Centres | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Growth of Trade and Emergence of Urban Centres in Peninsular India

In peninsular India, the expansion of trade and the rise of urban centres were closely linked to significant changes occurring in the region. These developments were driven by several interconnected factors:

These developments were driven by several interconnected factors:

1. Agricultural Growth and Technological Advances:

- In different parts of peninsular India, societal changes were driven by the growth of agriculture in major river valleys. This agricultural expansion was partly influenced by the iron technology associated with the peninsular Megalithic culture and advancements in irrigation methods.

- In certain regions, agricultural surpluses became available, contributing to economic growth.

2. Mauryan Expansion and Increased Connectivity:

- The Mauryan expansion in peninsular India facilitated greater contact with northern regions and stimulated the movement of traders, merchants, and other groups. The significance of the southern route (dakshina-patha), as highlighted in the Arthasastra, indicates the increased connectivity and trade opportunities during this period.

- Additionally, coastal contacts further enhanced trade networks, leading to significant changes in the existing systems of exchange in peninsular India.

3. Roman Demand and International Trade:

- From the late first century B.C., the demand for Indian goods by merchants and ships from the Roman world in the west brought peninsular India into close contact with international trade networks. This demand provided a major impetus for the growth of trade and urban centres.

4. Growth of Craft Specialization:

- The expansion of trade and urbanisation was also associated with the growth of craft specialization. Different skills were required for producing various craft items needed for local exchange and long-distance trade. Examples of such crafts include pottery, bead-making, glass-making, and weaving of cloth.

5. Uneven Impact Across Regions:

- It is important to note that the changes were not uniform across all parts of India. Some areas continued to exhibit earlier forms of culture. Furthermore, the pace and extent of change varied between the Deccan and the far south, with the Deccan experiencing more prominent changes initially.

Local Trade

In the far south of India, barter was the most prevalent method of transaction for local exchanges. Most items exchanged were for immediate consumption, with common barter items including salt, fish, paddy, dairy products, roots, venison, honey, and toddy.

Barter Items and Exchanges:

- Salt was often exchanged for paddy.

- Paddy was traded for milk, curd, and ghee.

- Honey was sometimes given in exchange for fish oil and liquor.

- Rice flakes and sugarcane could be bartered for venison and toddy.

- Luxury items like pearls and elephant tusks were rare in barter but could be exchanged for everyday articles like rice, fish, and toddy.

Loans in Barter System:

- Loans were also a part of the barter system in the Tamil south.

- A fixed quantity of an article could be borrowed and repaid later in the same kind and quantity. This practice was known as Kurietirppai.

Exchange Rates and Bargaining:

- Exchange rates were not fixed, and petty bargaining was the primary method for determining prices.

- Paddy and salt were the only items with a set exchange rate, with salt being bartered for an equal measure of paddy.

Barter in the Deccan under Satavahana Rule:

- Under the Satavahana rule in the Deccan, the use of coins was common, but barter continued to be practiced.

- Crafts such as pots, pans, toys, and trinkets were often bartered in rural areas.

Features of Barter System in Far South:

- Most items exchanged were consumption articles.

- Exchange was not profit-oriented.

- Distribution, like production, was subsistence-oriented.

Long Distance Overland Trade

- Trade contacts between northern and southern India can be traced back at least to the fourth century B.C., if not earlier. The resources of the regions south of the Vindhyan ranges were known to those in the north. Early Buddhist literature mentions a route from the Ganga valley to the Godavari Valley, known as the Dakshinapatha.

- Kautilya, the author of the Arthasastra, highlighted the advantages of this southern route, noting its abundance in conch-shells, diamonds, pearls, precious stones, and gold. The route passed through territories rich in mines and valuable merchandise, and Kautilya remarked that it was frequented by many traders.

- The Dakshinapatha connected various southern centers, including the city of Pratishthana, which later became the capital of the Satavahanas.

Items Traded Between North and South:

- Most items traded between north and south India were luxury articles, including pearls, precious stones, and gold.

- Textiles were also important in this trade, with fine varieties of silk, such as Kalinga silk, being highly valued by Tamil chieftains.

- The fine pottery known as Northern Black Polished ware (NBP) was another item traded, with NBP sherds found in the territory of the early Pandyas.

Herbs and Spices:

- Some herbs and spices, such as spikenard and malabathrum, were also brought to the south from the north.

- These herbs were shipped to the west for use in ointments.

Punch-Marked Coins:

- Northern traders also brought a large quantity of silver punch-marked coins to the south.

- These coins have been unearthed from various parts of south India and testify to the brisk commercial contacts between the north and south.

The long-distance trade with northern India, primarily in luxury items, benefited a small section of society, including the ruling elites and their followers.

Long Distance Overseas Trade

Indian Goods in Demand:

- Indian products such as spices, precious and semi-precious stones, timber, ivory, and various other articles were in high demand in western countries.

- South India was the main source of these goods, which were shipped to the west from very early times.

Commercial Contact with Rome:

- The direct trade with the Roman world, evident from the close of the first century B.C., was significant for the economy and society of peninsular India.

- Two stages can be identified in the commercial contact between Rome and peninsular India:

First Stage: Arabs as Middlemen:

- In the early stage, the Arabs acted as middlemen in the trade between Rome and India.

- They established commercial connections with India, using the sea as a trade highway before the beginning of the Christian era.

- The Arabs had some knowledge of the wind systems in the Arabian Sea, which they kept as a trade secret, allowing them to enjoy a monopoly in East-West trade.

Second Stage: Direct Contact:

- The second stage began when the Romans, under the guidance of a navigator named Hippalus, discovered the monsoon winds, enabling direct contact with India.

- This marked the beginning of increased commerce between Rome and peninsular India.

Roman Imports and Exports:

- The Romans brought various articles to the south Indian ports, including raw materials such as copper, tin, lead, coral, topaz, flint, and glass (used for making beads).

- They also imported finished products like the best quality of wine, fine clothes, ornaments, gold, silver coins, and different types of excellent pottery.

Categories of Exported Goods:

- Spices and medicinal herbs like pepper, spikenard, malabathrum, and cinnabar.

- Precious and semi-precious stones such as beryl, agate, carnelian, jasper, and onyx, as well as shells, pearls, and tusks.

- Timber items like ebony, teak, sandalwood, and bamboo.

- Textile items like coloured cotton cloth and muslin, as well as dyes like indigo and lac.

Payment and Collection of Merchandise:

- The Romans primarily paid for Indian articles in gold.

- Most export items were locally available, and the collection of merchandise in the Deccan and south India was done by Indian merchants.

- Wagons and pack animals were used for transporting goods to the ports.

Shipping of Merchandise:

- The shipping of merchandise to western lands was mostly carried out by foreign merchants, although there were also Indian maritime traders in the Deccan and south India.

- South India had commercial connections with Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, with important articles of trade including spices, camphor, and sandalwood.

- Merchants of Tamil origin likely initiated this trade, and Sri Lankan merchants also visited Tamilaham.

- Inscriptions in Tamil Brahmi characters refer to those who came from Elam (Sri Lanka), although details of this trade are not well-documented.

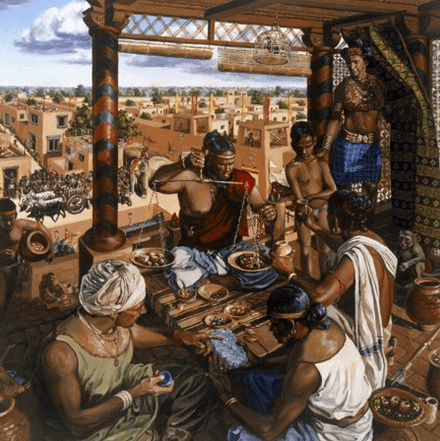

Commercial Organization in Ancient Tamilaham and Deccan

Local Transactions and Distribution Methods

Producers and Dealers in Small-Scale Transactions:

- In small-scale local transactions, producers often acted as dealers. For example, fishing and salt-making were exclusively carried out by the Paratava community, who lived in the coastal region of Tamilaham and devoted their entire time to these activities.

Distribution of Fish and Salt:

- Fish was distributed by the womenfolk of fishermen's families, who took it to neighboring areas, especially during village fairs and rural gatherings.

- Salt, being an essential item, was in high demand everywhere. A separate group known as umanas was responsible for the distribution of salt.

Salt Merchants (Umanas):

- In coastal areas and neighboring villages, umana hawker girls carried salt in headloads and bartered it mainly for paddy.

- In interior rural villages, salt was transported in large bags by carts drawn by bullocks or donkeys. The salt merchants moved in large groups called umanchathu, acting as collectors of merchandise from different parts of the region.

Organization of Salt Merchants:

- The umanas traveled in caravans with their families, and no organization other than the family unit is known among the salt merchants.

- Besides salt dealers, there were merchants dealing in corn, cloth, gold, sugar, etc., who are mentioned in ancient inscriptions as affluent donors of dwelling places to ascetics.

Traders’ Organization and Guilds:

- There is a single epigraphic reference to a traders’ organization in Tiruvellarai, where members were part of the nigama, a guild.

- While traders' organizations were rare in Tamilaham, merchants' guilds were common in the Deccan.

Trade Routes and Caravans

Trade Routes:

- One significant trade route ran from the Western hilly region to Kanchipuram, a prominent city on the east coast.

- Salt caravans and other merchants traversed these routes, often traveling in large groups.

Hazards of Travel:

- Travel was hazardous due to dense forests, hills, and the presence of wild tribes.

- Wayside robbery was a constant threat, leading merchants and caravans to employ their own guards in the absence of effective protection from rulers.

3. Trade under the Satavahanas

Trade Routes and Infrastructure:- In the territories under the Satavahanas, the main trade route to the Deccan from the north came from Ujjaini to the city of Pratishthana(Paithan), the capital of the Satavahanas.

- From Pratishthana, the route passed across the Deccan Plateau to the lower Krishna River and further south to important cities like Kanchi and Madurai.

- A network of roads developed early in the Christian era, linking producing areas in the interior with inland markets, towns, and port towns on the western coast.

- The fertile river valleys of Godavari and Krishna also had a network of routes connecting the interior with coastal towns.

Buddhist Cave Sites and Religious Centres:

- Many ancient Buddhist cave sites and religious centers in the Deccan were situated along these trade routes.

- These religious centers provided food, shelter, and even loans to merchant caravans.

Rulers’ Interest in Trade Routes:

- Rulers showed interest in the conditions of the trade routes by donating to Buddhist establishments located along the routes.

- They constructed rest houses at port towns and established watersheds along the routes.

- Officials were appointed for the upkeep of these facilities.

Ferries and Navigation:

- Trade routes often crossed rivers, where ferries were established, and tolls were collected from merchants.

- Some ferries were toll-free. Due to familiarity with the coastline and river systems, navigation on both sea and river was known to South Indians.

- Smaller boats were used for ferry-crossing and river navigation, while larger vessels were used for coastal navigation.

4. Maritime Trade

Coastal Navigation and Trade:- Navigation in Tamilaham was primarily coastal, with some trade connections with Sri Lanka.

- Sri Lankan traders are mentioned in ancient inscriptions of South India, while Tamil traders appear as donors in early inscriptions of Sri Lanka.

- These evidences indicate that traders from Tamilaham participated in maritime trade.

Sea-Borne Trade in the Deccan:

- Merchants in the Deccan were also engaged in sea-borne trade, with ships fitted out of Bharukaccha known from literature of this period.

Foreign Trade and Indian Traders:

- Merchants from peninsular India, particularly the Deccan, participated in foreign trade, with some Indian traders known to have been present in Egypt and Alexandria.

Royal Support for Maritime Trade:

- Royal authorities recognized the importance of maritime trade and provided facilities for traders.

- Ships arriving at Bharukaccha were piloted by local boats and conducted to separate berths at the docks.

- In the far south, chieftains in Tamilaham encouraged sea trade by erecting lighthouses, establishing wharves for unloading merchandise, and providing storage facilities and protection for goods at warehouses.

- Sea-borne trade in the far south and the Deccan exhibited features of “administered trade,” with the Deccan showing more prominent features compared to rudimentary levels in Tamilaham.

Coins

Local Coins:

- Kasu, Kanam, Pon, and Ven Pon– These are mentioned in ancient Tamil literature, but actual coins corresponding to these names have not been found.

- Kahapanas– Silver coins locally minted in the Deccan.

- Suvarnas– Gold coins, possibly from the Romans or the Kushans.

- Punch-marked coins– The earliest coins, minted in north-west and north India from the 6th-5th century B.C. and later in peninsular India.

- Other varieties of coins– Manufactured using techniques like casting and die-striking.

- Coins of local kings and families– Minted in their own names from the second century B.C., including coins from the Satavahana rulers.

- Kshatrapa silver coins– In great demand in regions like the northern Deccan, Gujarat, and Malwa.

Roman Coins:

- Yavana (Roman) ships– Brought large quantities of gold to Tamilaham in exchange for pepper.

- Roman wealth– Complaints about the wealth of the Roman Empire being drained off to foreign lands in exchange for luxury items.

- Roman coins found in hoards– Discovered in various places in peninsular India, indicating brisk Roman contact during this period.

- Types of Roman coins– Mostly gold and silver, with copper coins being rare.

- Transactions with Roman coins– Gold for large transactions, silver for smaller purchases. Some scholars believe Roman gold was accepted as bullion or used as ornamentation by South Indians.

- Roman coins and punch-marked coins– Circulated together, with imitations of Roman coins also in use, especially along the Coromandel Coast.

Revenue from Trade:

- Toll collection– For merchandise moving on pack animals and carts, known as Ulku.

- Kaveripumpattinam– A Chola port town where toll was levied on merchandise.

- Satavahana territory– More systematic taxation with customs duties and tolls on merchants at major towns.

- Karukara– Tax paid by artisans on their products.

- Revenue from trade and commerce– Considerable income derived by ruling authorities from trade activities.

Weights and Measures

- Coins and land measurement– Different denominations and land measured in terms of nivartanas.

- Measures of land– Such as Ma and Veli in the far south.

- Weight measurement– Known by means of balance, with minute weights balanced for transactions like weighing gold.

- Linear measurement– Expressed in terms of lengths of various grains and body parts, like finger and hand.

Urban Centers

- Port towns– Such as Bharukaccha, Sopara, Kalyana, with significant trade activities.

- Interior urban centers– Like Pratishthana, Tagara, Bhogavardhana, with agricultural hinterlands and groups of traders and artisans.

- Guilds– Organized activities of traders and craftsmen.

- Shipping facilities– For collection of commodities required in local and foreign exchange.

- Monetary system– Emergence of a monetary system for transactions.

- Writing– Spread of writing for accounting and registering transactions.

- Types of urban centers in Tamilaham– Rural exchange centres, inland market towns, and port towns.

- Rural exchange centres– Active due to regular exchange activities, but not fully urban in modern terms.

- Pattinams– Port towns like Kaveripumpattinam, Muziris, and Tyndis, focused on external trade and luxury items.

- Decline of urban centres– Linked to the decline of external trade.

Impact of Trade and Urban Centers on Society

- In the early period, trade and urban developments in Tamilaham did not significantly transform social life. Local exchanges were primarily focused on subsistence, involving goods used for regular consumption by various groups. Long-distance trade was mainly concerned with luxury items that circulated within the kinship circles of chieftains and their followers.

- The wealth and prosperity of individual merchants, as evident from their donations to monks, were not particularly remarkable. Unlike in some other regions, craftsmen and traders in Tamilaham were not organized into guilds. Instead, they operated as family members or close relatives, adhering to tribal norms and kinship relations.

- In contrast, the Deccan region exhibited a different scenario. Local trading groups played a crucial role in long-distance trade, ensuring that the benefits of this trade extended to other levels of society. The wealth and success of artisans, craftsmen, and traders in the Deccan were reflected in their contributions to Buddhist monasteries.

- Guild organizations of artisans and traders in the Deccan were pivotal in breaking down traditional kinship ties and fostering new relationships in the production of handicrafts and trading activities. The interplay between rulers, commercial groups, and Buddhist monastic establishments was instrumental in bringing about significant changes in the society and economy of the Deccan region.

|

367 videos|995 docs

|