Society in Early Medieval India | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

Introduction

For almost a century, we have been fed with the falacious colonialist and imprialist notion about the Indian society being static through the millennia. In this unit we will see that Indian social organisation between (8th 13th century) was extremely vibrant and responsive to changes taking place in the realms of economy, polity and ideas.

Sources for the Reconstruction of Society

Inscriptional sources:

- There is a vast amount of post-Gupta inscriptional data, running into thousands.

- These inscriptions are found in various languages and scripts.

- They help identify regional and local specifics while maintaining a broader view of the subcontinent.

Literary sources:

- Dharmashastras and other dharma-nibandhas provide insights into the fluctuations of the social system.

- Kavyas(poetic works), dramas, technical and scientific works, treatises, and architecture also serve as valuable sources.

- Examples of such works include:

- Kahāṇa's Rajatarangini

- Shriharsha's Naishadhiyacharita

- Merutunga's Prabandha Chintamani

- Soddhala's Udaya-Sundari Katha

- Jinasena's Adipurana

- The dohas of the Siddhas

- Medhatithi's and Vigyaneshwar's commentaries on the Manusmriti and Yajnavalkyasmriti

- Works like Manasollasa,Mayamata, and Aparajitapriccha

These sources are instrumental in reconstructing the social fabric of India during the examined period.

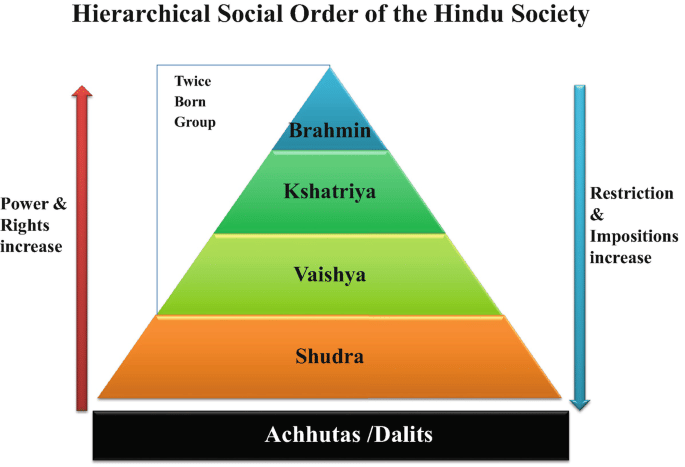

Brahmanical Perspective: Growing Rigidity

- The Brahmins were increasingly focused on preserving the traditional social order, influenced by the arrival of mlecchas(non-Vedic foreigners like the Huns, Arabs, and Turks), which instilled a sense of fear in them.

- Shankaracharya observed that the varna and ashramadharmas were in disarray.

- Dhanapala, an eleventh-century writer, also noted the chaos in the conduct of the varna order.

- Various rulers from the sixth to thirteenth centuries made grand claims about preserving the social order, as seen in their inscriptions.

- The term Varnashrama-dharma-sthapana, referring to the establishment of the varna and ashrama system, became common in contemporary inscriptions.

- A twelfth-century work, Manasollasa, even mentioned varnadhikarin(officer responsible for maintaining varna).

- This trend of tightening social ranks, making the social system rigid, and condemning attempts to change it was primarily the concern of Brahmanical lawgivers and political advisors with vested interests in maintaining the status quo.

- However, this was not a universal phenomenon.

Voices of Dissent

Non-Brahmanical Challenges to the Caste System:

- Throughout history, there have been challenges to the caste system from various sections of society.

- In the eleventh century, Jain scholar Amitagati argued that caste should be determined by personal conduct rather than birth.

- The Kathakoshprakarna, a Jain text, also questioned the superiority of Brahmins in the caste hierarchy.

- The Latakamelaka mentioned a Buddhist monk who dismissed the significance of caste, viewing it as baseless and a source of pollution.

- Kshmendra, a Kashmiri writer, criticized caste and clan vanity as a social disease, positioning himself as a healer of this affliction.

- The Padmapurana presented a conflict between two ideologies regarding Shudras: one advocating a life of poverty and the other emphasizing the importance of wealth.

- Another eleventh-century work proposed a social ranking system based on occupations rather than birth. Priests of different religions were labeled as hypocrites, and the social classification included categories like:

- Highest: Chakravartins (universal monarchs).

- High: Feudal elite.

- Middle: Traders, moneylenders, and possessors of livestock.

- Lower: Small businessmen, petty cultivators.

- Degraded: Members of artisan and crafts guilds.

- Highly Degraded: Chandalas and those in ignoble occupations.

- This categorization reflects a focus on economic factors in determining social status.

- Despite biases, these attempts at reconstruction were more rational compared to the traditional Brahmanical perspective.

Changing Material Base and the New Social Order

Conflicting trends indicate that Indian social organization was in a state of flux and far from harmonious, primarily due to the changing economic structure of society.

The mechanics of the social system are difficult to understand without considering the improving economic conditions of a significant portion of the lower classes.

Agrarian expansion driven by the growing phenomenon of land grants transformed the entire social outlook. This expansion was accompanied by:

- A boost to localization tendencies

- Fluctuations in the urban setting

- Connections with the monetary system

- Increased social and economic immobility and the subjugation of both peasantry and non-agricultural laborers

- The emergence of a hierarchy led by the ruling landed aristocracy

A new social ethos was emerging, with the evolving Indian economy conducive to feudal formation. In the political realm, many power centers exhibited feudal tendencies based on graded land rights.

The social landscape was heavily influenced by the rapid economic changes.

These social changes challenge the notion of a static Indian social organization, which was propagated by colonialist and imperialist historians. Recent writings, especially over the last three decades, have rightly emphasized the dynamism and vibrancy of the Indian social fabric, highlighting its connections with evolving economic patterns.

The New Social Ethos

Social organization between the 8th and 13th centuries was characterized by:

- Changes in the varna system, including the transformation of shudras into cultivators, bringing them closer to the vaishyas.

- The emergence of a new brahmanical order in Bengal and South India, where intermediary varnas were absent.

- The rise of a new literate class striving for a place within the varna system.

- A significant increase in the number of new mixed castes.

- Unequal distribution of land and military power, leading to the emergence of feudal ranks that cut across varna distinctions.

- Growing evidence of social tensions.

Emergence of Shudras as Cultivators:

- The expansion of rural space and agricultural activities contributed to changes in the social order. This led to a significant challenge to the brahmanical social order and a redefinition of varna norms. Indicators of this change include:

- Post-Gupta law books include agriculture in the samanaya-dharma (common occupation) of all varnas.

- The smriti of Parashar emphasizes that brahmanas could engage in agricultural activities, particularly through the labor of shudras. It also instructs brahmanas to treat oxen properly and offer fixed quantities of corn to the King, Gods, and fellow brahmanas.

Bridging the gap between vaishyas and shudras:

- In the post-Gupta centuries, vaishyas began to lose their identity as a distinct peasant caste.

- Hsuan-Tsang mentions shudras as agriculturists.

- Al-Biruni notes the absence of any distinction between vaishyas and shudras. By the eleventh century, they were treated similarly, both ritually and legally. For example, both vaishyas and shudras were punished with amputation of the tongue for reciting Vedic texts.

- The Skanda Purana describes the poor conditions of vaishyas.

- Texts from the eighth century indicate that numerous mixed castes emerged from marriages between vaishya women and men of lower castes.

- Many Tantric and Siddha teachers were shudras engaged in occupations such as fishing, leatherworking, washing, and blacksmithing.

- Certain shudras, known as bhojyanna, prepared food that could be consumed by brahmanas.

- There were also anashrita shudras (independent shudras) who were well-to-do, sometimes becoming members of local administrative committees and even entering the ruling aristocracy. However, such achievements were rare, as dependent peasants were still needed.

- The approximation of vaishyas and shudras was essential for the early medieval economic and political setup, characterized by a self-sufficient local economy and the emergence of a dominant class of rural aristocracy. Dependent peasants, ploughmen, and artisans were crucial for this setup.

- Despite these changes, brahmana orthodoxy persisted. Parashar, for example, threatened shudras who neglected their duty of serving the dvijas with dire consequences.

- Some orthodox sections of the jainas also believed that shudras were ineligible for religious initiation.

Absence of Intermediary Varnas in Bengal and South India:

- The new brahmanical order in Bengal and South India included only brahmans and shudras, with no intermediary varnas. This was due to:

- The tendency to eliminate distinctions between vaishyas and shudras.

- The influence of non-brahmanical religions in these regions, where tribal and non-brahmanical populations were integrated into the brahmanical system as shudras.

- The Brahmavaivarta Purana, attributed to thirteenth-century Bengal, mentions tribal groups like Agaris, Ambashthas, Bhillas, Chandalas, and Kaunchas being included as shudras in the brahmanical order.

- Similar patterns were observed with the Abhiras in the Deccan region.

- The Vallalacharita (12th century), related to King Vallala Sena of Bengal, describes the reordering of the social structure.

- In the South, the elimination of intermediary varnas is evident in the status of scribes. Groups such as Kayasthas, Karanas, Lekhakas, and lipikaras were categorized as shudras, as were gavundas (modern-day Gowdas in Karnataka) in medieval Deccan.

Rise of a New Literate Class:

- The land grants involved various aspects such as land transactions, keeping ownership records, and maintaining measurement statistics.

- This process required a class of specialists and a large number of scribes.

- The Kayasthas were just one class among many writers and record keepers.

- Although the first Kayastha is mentioned in Gupta inscriptions from Bengal, post-Gupta inscriptions show a diverse range of people involved in record-keeping activities.

- Besides Kayasthas, other scribes included karanas, karanikas, pustapala, lekhaka, divira, aksharachanchu, dharmalekhin, akshapatalika, and others.

- Initially, these scribes came from different varnas, but over time, they evolved into distinct castes with specific marriage restrictions.

- The use of terms like Kula and Varnsha with Kayasthas from the eleventh century and terms like jati and gyati from the twelfth and thirteenth centuries indicate the emergence of the Kayastha caste.

- Individual Kayasthas began to take on prominent roles in learning and literature.

- Tathagatarakshita of Orissa, a Kayastha by caste and from a family of physicians, was a renowned professor of Tantras at Vikrarnashila University in Bihar during the twelfth century.

Phenomenal Increase in the Rise of New Mixed Castes:

- This was a notable characteristic of social changes during the referenced centuries.

- The Brahmavaivarta Purana concept of deshabheda(regional/territorial differences) led to variations in castes.

- A village called Brihat-Chhattivanna, inhabited by 36 varnas, is mentioned in a tenth-century inscription from Bengal.

- No varna remained homogeneous; they fragmented due to territorial affiliation,purity of gotras, and the pursuit of specific crafts, professions, and vocations.

Amongst Brahmanas:

- The proliferation of castes was particularly pronounced among Brahmanas.

- They expanded beyond their traditional sixfold duties, taking on high governmental roles such as ministers, purohitas, and judges, and even military functions.

- For instance, the senapati of Prithviraj Chauhan was a Brahmana named Skanda.

- Inscriptions from Pehoa and Siyadoni, dated in the ninth-tenth century, mention Brahmanas as horse dealers and betel sellers.

- In the eleventh century, the Kashmiri writer Kshemendra noted Brahmanas engaging in artisan roles, dancing, and selling wine, butter-milk, salt, and other goods.

- Functional distinctions among Brahmanas were reflected in titles such as Shrotriya, pandita, maharaja pandita, dikshit, yajnik, pathaka, upadhyaya, thakkura, and agnihotri.

- The Mitakshara commentary on Yagyavalkya's Smriti discusses a ten-fold gradation of Brahmanas, ranging from Deva(a professor devoted to religion and shastras) to Chandal(who does not perform sandhya three times a day).

- Divisions within the Brahmana varna were also influenced by territorial affiliations.

- In North India, there were Sarasvat, Kanyakubja, Maithi, Ganda, and Utkal Brahmanas.

- In Gujarat and Rajasthan, Brahmanas were identified by their mula(original place of habitation) and divided into Modha, Udichya, Nagara, etc.

- By the late medieval period, Brahmanas were divided into about 180 mulas.

- Feelings of superiority and migration caused divisions, with certain regions considered papadeshas(impious regions) like Saurashtra, Sindh, and Dakshinapath.

Amongst Kshatriyas:

- Post-eighth century, the ranks of kshatriyas increased significantly.

- Various works mention 36 clans of Rajputs in northern India alone, emerging from different population strata including kshatriyas, brahmanas, other tribes, and assimilated foreign invaders.

- While the kshatriya varna was traditionally associated with rulership, the ideology accepted non-kshatriya rulers as kshatriyas.

- Respectable captives were enrolled among tribes like Shekhavat and Wadhela, while lower kinds were allocated to castes like Kolis, Khantas, and Mers.

- Some new kshatriyas were termed Samskara-Varjita(deprived of ritualistic rites), possibly due to inferior rites during their admission into the brahmanical social order.

Amongst Vaishyas and Shudras:

- Vaishyas were also identified by regional affiliations, leading to groups like Shrimal’s, Palliwals, Nagar, and Disawats.

- Shudras exhibited heterogeneity, performing various functions such as agricultural labor, petty peasants, artisans, craftsmen, servants, and attendants.

- The Brahma Vaivarta Purana lists around one hundred castes of shudras, with subdivisions based on regional and territorial affiliations.

- Some shudra castes emerged through specific industrial processes, like Padukakrit and Charmakara (shoe makers, leather workers).

- The crystallization of crafts into castes was a complementary phenomenon, with castes like napita, modaka, tambulika, suvarnakara, sutrakara, malakara, etc., arising from various crafts.

- These castes increased with the growth of the ruling aristocracy, and their characterization as ashrita reflected their dependence.

- The transfer of trading guilds(shrenis or prakritis) to brahmana donees indicated their subjection and immobility.

- An inscription from 1000 A.D., belonging to Yadava mahasamanta Bhillama-II, defines a donated village comprising eighteen guilds, which also functioned as castes.

Land Distribution, Feudal Ranks and Varna Distinctions

Impact of Power Dispersal and Land Distribution on Social Structure:

- The dispersal of power and its connection to land distribution significantly influenced the social structure of the time.

- A key aspect of this influence was the emergence of feudal ranks that transcended traditional varna (social class) distinctions.

- The ruling aristocracy was no longer exclusively comprised of kshatriyas (warriors); individuals from various varnas could attain feudal ranks.

- The text Mansara, a treatise on architecture, highlights that individuals of any varna could achieve the two lower military ranks in the feudal hierarchy: praharka and astragrahin. This indicates the openness of feudal ranks to all varnas.

- The conferral of titles such as thakur,raut, and nayaka was not limited to kshatriyas or Rajputs. These titles were also granted to kayasthas and other castes who received land and served in the army.

- According to Kulluka’s commentary on the Manusmriti, there was a tendency for larger merchants to join the ranks of the ruling landed aristocracy.

- In Kashmir, the title rajanaka, meaning "nearly a king," became associated with the brahmanas and later evolved into the family name razdan.

- Feudal titles were also awarded to artisans. For example, the Deopara inscription of Vijayasena mentions Shulapani, the head of artisans in Varendra (Barind, now in Bangladesh), who held the title ranaka.

- The symbols and insignia of social identity among feudal rank holders were closely tied to their landed possessions.

- Badges of honor, such as fly whisks, umbrellas, horses, elephants, palanquins, and the acquisition of pancha-mahashabda, were determined by one's specific place in the feudal hierarchy.

- For instance, chakravartis and mahasamantas were allowed to erect the chief gate (sinhadvar), a privilege not granted to lesser vassals.

- The provision of varying sizes of houses for different grades of vassals and officials was also a consequence of the impact of unequal land holdings.

Increasing Social Tensions

Social Changes and Tensions in Post-Eighth Century India:

- Despite changes and developments that transcended varna distinctions, the social changes after the eighth century were not harmonious or egalitarian.

- Social tension was inevitable in a society with significant inequality. Although the shudras were improving their status, untouchability remained ingrained in the social fabric.

- During Vastupala's governorship in Cambay, he built platforms to prevent mingling of different castes at shops selling curd.

Major Factors for the Growth of Untouchability:

- Pursuit of impure occupations

- Guilt of prohibited acts

- Adherence to heretical acts

- Physical impurities

- The Brihad Naradiya Purana indicates the exclusion of shudras from places of worship. Chandalas and dombas were required to carry sticks to announce their presence and avoid contact with others.

- Although brahmanical lawgivers were concerned about women's proprietary rights, particularly regarding stridhan, the practice of sati began to emerge during this period.

- The Harshacharita by Banabhatta mentions King Harsha's mother performing sati before her husband's death.

- The Rajatarangini chronicles the performance of sati in royal families in Kashmir.

- Archaeological evidence, such as sati-satta plaques found in North and South India, supports the prevalence of sati.

- There were sectarian rivalries, with a Jain brahmana considered an outcaste.

- In the Latakamelaka, two brahmanas accuse each other of being abrahmanya without clear reason.

- Religious sects multiplied, with differences in rituals, food, and dress causing splits.

- For example, Buddhism split into 18 sects, and the Jainas in Karnataka had seven sects.

- Karnataka also saw conflicts between the Lingayats and Virashaivas.

- Religions that aimed to abolish caste distinctions were eventually absorbed into the caste system.

- The land grant economy fueled competition among religious sects for land, leading to social tension. Many religious establishments became landed magnates.

- Some rulers, like Avantivarman of the Mattamayara region and a Cedi King of Dahala, dedicated their kingdoms to be religious heads of the Shaiva Siddharta school.

- The Protestant movement of the vidhi-chaitya sect of Jainas criticized greedy Jaina ascetics for land grabbing.

- The rise of the kayasthas, a new literati class, challenged the brahmanas' position.

- Kayastha Tathagata-rakshita of Orissa became a renowned professor of Tantras at Vikramashila University.

- Kshemendra of Kashmir noted that the rise of kayasthas led to a loss of economic privileges for brahmanas.

- In Kashmir, members of the temple-purohita corporation used prayopavesha(hunger strikes) to address grievances.

- Rural tensionswere evident in:

- Damara revolts in Kashmir

- Rebellion of the kaivarattas in Bengal

- Acts of self-immolation in Tamil Nadu due to land encroachments

- Land appropriation by shudras in Pandya territory

|

367 videos|995 docs

|

FAQs on Society in Early Medieval India - History Optional for UPSC

| 1. What were the key sources for the reconstruction of society in early medieval India? |  |

| 2. How did the Brahmanical perspective contribute to the growing rigidity in social structures during this period? |  |

| 3. What were some significant voices of dissent against the established social order in early medieval India? |  |

| 4. How did changes in the material base influence the new social order in early medieval India? |  |

| 5. What were the implications of land distribution and feudal ranks on social tensions in early medieval India? |  |