Structure and Reproduction of Mycoplasma | Botany Optional for UPSC PDF Download

What is Mycoplasma?

Mycoplasma is a bacterium that causes infections in different areas of your body including your respiratory, urinary, and genital tracts. Mycoplasma infections cause mild symptoms

Mycoplasma is a genus of bacteria characterized by several unique features:

Mycoplasma is a genus of bacteria characterized by several unique features:

- Lack of Cell Wall: Mycoplasma bacteria are distinct in that they lack a cell wall around their cell membranes. This feature sets them apart from many other bacteria.

- Small Size: Mycoplasmas are the smallest free-living prokaryotes. They are exceptionally tiny microorganisms.

- Resistance to Antibiotics: Due to their absence of a cell wall, mycoplasmas are naturally resistant to antibiotics that target cell wall synthesis, such as beta-lactam antibiotics.

- Parasitic or Saprotrophic: Mycoplasmas can exist as parasitic organisms, living off a host, or as saprotrophic organisms, decomposing organic matter. Some species are pathogenic in humans.

- Human Pathogens: Certain Mycoplasma species, like M. pneumoniae, can cause respiratory disorders such as "walking" pneumonia. M. genitalium is believed to be associated with pelvic inflammatory diseases.

- Size and Shape Variation: Mycoplasma species exhibit a range of sizes and shapes. For example, M. genitalium is flask-shaped, measuring about 300 x 600 nanometers, while M. pneumoniae is more elongated, with dimensions of about 100 x 1000 nanometers.

These unique characteristics make Mycoplasma bacteria an intriguing group of microorganisms with both medical and biological significance.

Etymology

The term "mycoplasma" has an interesting etymology and history:

- The word "mycoplasma" is derived from the Greek words "mykes," which means fungus, and "plasma," which means formed or molded.

- Mycoplasmas were first discovered by Louis Pasteur in 1843 while he was studying the organisms responsible for pleuropneumonia in cattle. He initially named them "Pleuropneumonia-like organisms" (PPLO) but was unable to isolate them in pure cultures.

- In 1889, Albert Bernhard Frank described these microorganisms as an altered state of plant cell cytoplasm resulting from infiltration by fungus-like microorganisms.

- Mycoplasmas were first isolated in pure cultures by French bacteriologists E. Nocard and E.R. Roux in 1898 from the pleural fluids of cattle affected with pleuropneumonia.

- The term "mycoplasma" was coined in 1929 by Nowak. He proposed the genus name "Mycoplasma" for certain filamentous microorganisms that were thought to have both cellular and acellular stages in their lifecycles. This could explain how they were visible with a microscope but could pass through filters impermeable to other bacteria.

- Phytopathological mycoplasmas, which infect plants, were later renamed "phytoplasmas." Phytoplasmas typically reside in the phloem tissue of plants and can cause symptoms like yellowing, phyllody, and witch's brooms.

- Over time, various groups of mycoplasma-like organisms have been discovered and categorized into different groups, including mycoplasmas (infect animals), phytoplasmas (infect plants), spiroplasmas (infect plants and insects), Archeoplasmas (infect animals, plants, and insects), and entomoplasmas (infect insects and plants). This classification reflects the diversity and adaptability of these microorganisms.

Important Characteristics of Mycoplasmal

Mycoplasmas exhibit several important characteristics:

- Smallest Prokaryotic Organisms: Mycoplasmas are the smallest prokaryotic organisms. They lack a cell wall, and their plasma membrane serves as the outer boundary of the cell.

- Pleomorphic: Due to the absence of a cell wall, mycoplasmas can change their shape and exhibit pleomorphism, meaning they can have various shapes and forms.

- Absence of Nucleus and Membrane-Bound Organelles: Mycoplasmas lack a true nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles commonly found in eukaryotic cells.

- Genetic Material: Mycoplasmas have a single DNA duplex as their genetic material, and it is naked, meaning it is not enclosed by a nuclear membrane.

- Ribosomes: The ribosomes in mycoplasmas are of the 70S type, which is a characteristic feature of prokaryotic cells.

- Small Genomes: Mycoplasmas have small genomes, resulting in simplified metabolic pathways. They have undergone genome reduction and lost various metabolic capabilities, including the ability to synthesize peptidoglycan precursors.

- Minimal Genome Size: The genomes of mycoplasmas are among the smallest found in bacteria, typically ranging from 0.7 to 1.7 megabases (Mb). Some human pathogens like Mycoplasma genitalium, M. pneumoniae, and Ureaplasma urealyticum have genomes with fewer than 1,000 genes, indicating a minimal genome size.

- Limited Metabolic Capacity: Mycoplasmas have a limited number of genes because they rely on their host's biosynthetic capacity for various macromolecules. They have lost genes responsible for synthesizing amino acids, purines, pyrimidines, and fatty acids.

- Replicating Disc: Mycoplasmas possess a replicating disc at one end of their cell, which aids in the replication process and separation of genetic material.

- Sterol Requirement: Sterols are an essential component of the mycoplasma plasma membrane. They play a role in maintaining osmotic stability, particularly in the absence of a cell wall.

- Colony Appearance: When grown on agar, most mycoplasmas form colonies with a characteristic "fried egg" appearance. They grow into the agar surface at the center of the colony and spread outward on the surface at the colony's edges.

- Heterotrophic Nutrition: Mycoplasmas are heterotrophic in nutrition, meaning they obtain their nutrients from organic sources. Some live as saprophytes, but the majority are parasitic, infecting plants and animals. Most species also require sterols for growth, which they acquire from their host organisms.

These characteristics make mycoplasmas distinct and highlight their unique biological properties, including their ability to adapt to different environments and host organisms.

Habit and Habitat of Mycoplasmal

Mycoplasmas have a diverse distribution across various habitats and can be found in a range of environments:

- Diverse Habitats: Mycoplasmas are distributed in various habitats, including sewage, plants, animals, insects, humus, and hot water springs. They are known to thrive in high-temperature environments.

- Association with Plants: Some mycoplasma-like bodies have been associated with diseased plants and are found in the phloem tissues of these plants.

- Association with Humans: In humans, at least eleven serologically and biologically distinct mycoplasmas have been identified. Mycoplasma orale and M. salivarium are commonly found in the mouths of healthy adults, while M. hominis is prevalent in sexually active adults.

- Disease-Causing: Mycoplasmas are known to cause various diseases in humans, including primary atypical pneumonia (PAP) in the mouth, pharynx, and genito-urinary tract, as well as tonsillitis. They have also been associated with conditions such as bacterial vaginosis in women and pelvic inflammatory disease caused by M. genitalium.

- Infant Health: Mycoplasmas are linked to health issues in infants, including infant respiratory distress syndrome, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, and intraventricular hemorrhage in preterm infants.

- Human-Associated Species: Some mycoplasma species are primarily associated with humans and are assumed to have been contracted from non-human hosts. These species include M. amphoriforme, M. buccale, M. faucium, M. fermentans, M. genitalium, M. hominis, M. incognitus, M. lipophilum, M. orale, M. penetrans, M. pirum, M. pneumoniae, M. primatum, M. salivarium, M. spermatophilum, and others.

The wide distribution of mycoplasmas across various habitats and their association with both plants and animals highlights their adaptability and ability to thrive in diverse ecological niches.

Classification of Mycoplasmal

Mycoplasmas are classified based on their nutritional requirements, and they fall into three genera:

- Mycoplasma:

- These mycoplasmas require cholesterol for their growth.

- They are known to parasitize animals, including humans, by causing damage to mucous membranes and various joints in the body.

- Acholeplasma:

- Acholeplasmas do not require cholesterol for their growth.

- They can be found in sewage water and soil as saprophytes (organisms that feed on dead organic matter), as well as in vertebrates and plants as parasites.

- Thermoplasma:

- Thermoplasmas, like acholeplasmas, do not require cholesterol for their growth.

- These aerobic microorganisms thrive in acidic pH conditions between 0.96 and 3.0, with an optimal temperature for growth at 59°C.

- This classification is based on their nutritional preferences and habitats, which vary among these different genera of mycoplasmas.

Morphology of Mycoplasma

Mycoplasmas exhibit unique morphological characteristics:

- Intermediate Nature: Mycoplasmas are considered intermediates between viruses and bacteria. They can pass through many filters and grow on media without the need for living tissue.

- Small and Unicellular: They are very small, unicellular, and typically non-motile prokaryotic organisms.

- Filterable: Mycoplasmas are so tiny that they can pass through bacteria filters.

- Antibiotic Resistance: They are highly resistant to penicillin but can be inhibited by tetracyclines.

- Colony Appearance: When grown in cell-free media, they form colonies with a distinctive "fried egg-shaped" appearance.

- Pleomorphic: Mycoplasmas are highly pleomorphic, meaning they can take on various shapes. They may appear as small coccoid bodies, ring forms, or filamentous forms, some of which may be branched.

- Lack of Rigid Cell Wall: Mycoplasma cells lack a rigid cell wall and are bounded by a triple-layered unit membrane. They cannot synthesize cell wall material and require sterols for growth.

- DNA and RNA Content: Mycoplasma cells contain both DNA and RNA.

- Reproduction: The reproductive methods of mycoplasmas are still controversial. Reproduction may involve the development of tiny coccoid structures called elementary bodies, which are released through fragmentation, binary fission, or budding.

- Variable Shapes: Mycoplasmas can vary in shape, including being spherical, polymorphic, or irregularly filamentous. Filaments may be either branched or unbranched.

These characteristics make mycoplasmas distinct from other microorganisms and contribute to their unique biology.

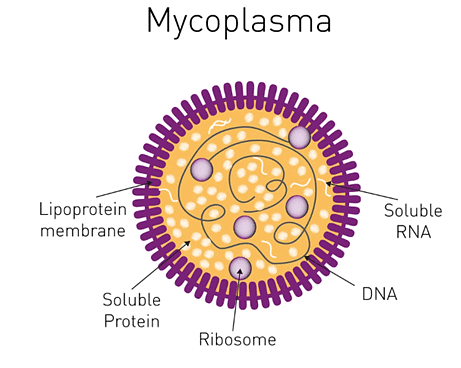

Cell Structure of Mycoplasma

The cell structure of Mycoplasma is characterized by several key features:

- Size: Mycoplasma cells are small, with diameters ranging from 300 nm to 800 nm.

- Absence of Rigid Cell Wall: Unlike many other bacteria, mycoplasmas lack a rigid cell wall. Instead, they are surrounded by a triple-layered lipo-proteinaceous unit membrane, which is approximately 10 nm thick. This unit membrane encloses the cytoplasm of the cell.

- Cytoplasmic Contents: Within the cytoplasm, mycoplasmas contain RNA (ribosomes) and DNA. The ribosomes are approximately 14 nm in diameter and belong to the 70S type.

- DNA Characteristics: The DNA in mycoplasmas is double-stranded and forms a helical structure. It can be distinguished from bacterial DNA by its relatively low guanine and cytosine (G and C) content.

- Nucleic Acid Content: Mycoplasmas have a lower nucleic acid content compared to other prokaryotes. The DNA content is approximately four percent, and the RNA content is about eight percent, which is less than half of what is typically found in other organisms.

- Blebs: In some species of mycoplasma, such as M. gallisepticum, polar bodies called "blebs" can protrude from one or both ends of the cell. These blebs are considered to be sites of enzymatic activities and may play a role in attachment during the infection process.

These structural characteristics contribute to the unique biology of mycoplasmas, including their ability to infect hosts and cause diseases.

Reproduction in Mycoplasma

Reproduction in Mycoplasma involves budding and/or binary fission. Here's how the process works:

- Budding: Mycoplasma cells can reproduce by budding. During this process, the parent cell forms a small protrusion or bud on its surface. This bud eventually grows and separates from the parent cell, becoming an independent daughter cell. These newly formed daughter cells are referred to as "elementary bodies" or "minimal reproductive units." The size of these elementary bodies typically ranges from 330 nm to 450 nm, making them some of the smallest independent living entities known.

- Binary Fission: Mycoplasma cells can also reproduce through binary fission, a process where the parent cell divides into two roughly equal-sized daughter cells. This division occurs without the presence of a rigid cell wall, which allows the mycoplasma cell to change its shape and size during the process.

These reproductive mechanisms enable mycoplasma to multiply and colonize their host environments.

Transmission of Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma-like organisms (MLO) or phytoplasmas are typically found in the phloem of host plants and are transmitted from one host to another through various insect vectors.

Here's how the transmission of Mycoplasma occurs:

- Vector Transmission: Mycoplasma is transmitted by insect vectors, primarily leafhoppers. Some may also be transmitted by other insects like psyllids, treehoppers, plant hoppers, and possibly aphids and mites. These insects act as carriers of the pathogen.

- Multiplication in Vector: Some mycoplasmas are known to infect various organs of their leafhopper or psyllid vectors and multiply within the cells of these insects.

- Transmission Incubation Period: The vectors do not transmit the phytoplasma immediately after feeding on an infected plant. Instead, there is an incubation period of 10 to 45 days, which depends on the temperature. During this time, the phytoplasma multiplies and becomes transmissible by the insect vector.

- Vector Feeding: Once the incubation period is completed, the infected vector insect can transmit the phytoplasma to a healthy plant when it feeds on it. The phytoplasma is then introduced into the phloem of the new host plant.

This mode of transmission allows mycoplasmas to spread from infected plants to healthy ones, leading to the infection of a broader range of host plants.

Diseases Caused by Mycoplasma

Mycoplasma bacteria can cause various diseases in plants, humans, and animals. Here are some of the diseases caused by Mycoplasma:

Plant Diseases

- Little leaf disease of brinjal: Affects eggplants, causing stunted growth and distorted leaves.

- Bunchy top of papaya: Leads to the bunching of leaves and stunted growth in papaya plants.

- Big bud of tomato: Causes abnormal growth and enlargement of tomato buds.

- Witches broom of legumes: Results in the formation of abnormal, broom-like structures on legume plants.

- Yellow dwarf of tobacco: Causes yellowing and stunted growth in tobacco plants.

- Clover dwarf: Affects clover plants, leading to dwarfing and poor growth.

- Cotton virescence: Results in the virescence or abnormal green coloration of cotton plants.

Human Diseases

- Primary atypical pneumonia (PAP) by Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Causes a type of pneumonia known as "walking pneumonia," characterized by mild symptoms and a prolonged course.

- Mycoplasma hominis: Can cause pleuropneumonia, prostatitis, and genital inflammations in humans.

- Mycoplasma fermentans: Associated with infertility in men.

Animal Diseases

- Mycoplasma agalactia: Causes agalactia (lack of milk production) in goats and sheep.

- Mycoplasma mycoides: Responsible for pleuropneumonia in cattle.

- Mycoplasma bovigenitalium: Leads to inflammation of the genitals in various animals.

These diseases can have significant economic and health impacts on both plants and animals, as well as human health in the case of respiratory infections caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

Key Points

Mycoplasma, a genus of bacteria characterized by the absence of a cell wall around their cell membranes, can have significant implications in both human and animal health, as well as plant diseases.

Here are some key points summarizing Mycoplasma:

- Pathogenic Species: Some Mycoplasma species are pathogenic in humans and can cause respiratory disorders, such as "walking" pneumonia (M. pneumoniae), and are associated with conditions like pelvic inflammatory diseases (M. genitalium).

- Etymology: The term "mycoplasma" is derived from the Greek words "mykes" (fungus) and "plasma" (formed).

- Discovery: Mycoplasmas were first discovered by Louis Pasteur in 1843 while studying the causal organisms of pleuropneumonia in cattle. However, they were not isolated in pure cultures at that time.

- Isolation: French bacteriologists E. Nocard and E.R. Roux successfully isolated Mycoplasma from pleural fluids of cattle affected with pleuropneumonia in 1898.

- Naming: The name "mycoplasma" was proposed by Nowak in 1929. Mycoplasmas have since been classified into various groups based on their habitat and characteristics.

- Pleomorphic: Mycoplasmas lack a rigid cell wall, allowing them to change shape and exhibit pleomorphism.

- Genomic Characteristics: Mycoplasma genomes are among the smallest in the bacterial world, ranging from 0.7 to 1.7 Mb. Some human pathogens, like Mycoplasma genitalium and M. pneumoniae, have fewer than 1,000 genes, indicating minimal genome sizes.

- Habitat: Mycoplasmas are found in various environments, including sewage, plants, animals, insects, humus, and hot water springs. They can also be present in the phloem tissues of diseased plants.

- Three Genera: Mycoplasmas are categorized into three genera based on their nutritional requirements: Mycoplasma, Acholeplasma, and Thermoplasma.

- Intermediate Between Viruses and Bacteria: Mycoplasmas are considered intermediate between viruses and bacteria because they can pass through many filters, grow in cell-free media, and exhibit pleomorphism.

- Transmission: Mycoplasma-like organisms (MLO) or phytoplasmas can be transmitted from host to host in plants through leaf hoppers, psyllids, treehoppers, plant hoppers, aphids, and mites.

- Diseases: Mycoplasmas can cause diseases in plants (e.g., Little leaf disease, Bunchy top, Witches broom), animals (e.g., Agalactia in goats, Pleuropneumonia in cattle), and humans (e.g., Primary atypical pneumonia, infertility).

- Antibiotic Resistance: Mycoplasmas are highly resistant to penicillin but can be inhibited by tetracyclines.

These characteristics highlight the diverse and impactful nature of Mycoplasma bacteria in various ecosystems and their potential to cause diseases in different organisms.

Terminology

- Aerobic Respiration: The process by which cells use oxygen to produce energy from glucose or other organic molecules.

- Antibiotic: A chemical substance that can kill or inhibit the growth of bacteria, often used to treat bacterial infections.

- Antibody: A Y-shaped protein produced by the immune system in response to foreign substances (antigens) such as bacteria, viruses, or other pathogens. Antibodies help the immune system recognize and neutralize these invaders.

- Bacterium (Bacteria, Plural): A type of microorganism that consists of single-celled, prokaryotic organisms.

- Binary Fission: A method of asexual reproduction in which a single cell divides into two separate daughter cells, each genetically identical to the parent cell.

- Budding: A form of asexual reproduction in which a new individual begins as an outgrowth or "bud" on the parent organism and eventually separates to become an independent organism.

- Cell: The fundamental structural and functional unit of all living organisms.

- Chromosome: A long, thread-like structure composed of DNA and associated proteins found in the nucleus of eukaryotic cells. Chromosomes carry genetic information.

- DNA (Deoxyribonucleic Acid): A molecule that carries the genetic instructions necessary for the growth, development, functioning, and reproduction of all known living organisms and many viruses.

- Decomposer: Organisms such as certain fungi and soil bacteria that break down dead plants, animals, and organic matter, converting them into simpler substances and recycling nutrients in ecosystems.

- Enzyme: A type of protein that acts as a biological catalyst, speeding up chemical reactions within cells by lowering the activation energy required for these reactions to occur.

- Host Cell: A cell that has been infected by a virus or another microorganism and serves as a host for the replication and survival of the invading organism.

- Microorganism (Microbe): A small, living organism that can only be seen with the aid of a microscope. Microbes include various groups such as bacteria, archaea, protozoa, algae, fungi, and viruses.

- Organelle: A specialized, membrane-enclosed structure within a cell that performs specific functions necessary for the cell's survival and functioning.

- Pathogen: An organism, such as a bacterium, virus, fungus, or parasite, that causes diseases or infections in its host.

- Toxin: A substance, often produced by certain microorganisms, that is poisonous and harmful to other organisms when it enters their bodies.

|

179 videos|140 docs

|

FAQs on Structure and Reproduction of Mycoplasma - Botany Optional for UPSC

| 1. What is Mycoplasma? |  |

| 2. What is the etymology of the term "Mycoplasma"? |  |

| 3. Where do mycoplasmas usually live? |  |

| 4. How are mycoplasmas classified? |  |

| 5. How do mycoplasmas reproduce? |  |

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|