The Early Administrative Structure | History Optional for UPSC PDF Download

| Table of contents |

|

| Dual System (Diarchy) of Government (1765-1772) |

|

| The Regulating Act (1773) |

|

| Criticism of the Regulating Act 1773 |

|

| From Diarchy to Direct Control |

|

| Judicial System |

|

Dual System (Diarchy) of Government (1765-1772)

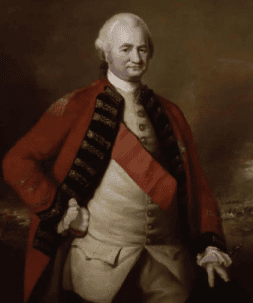

- After the Treaty of Allahabad (1765), Robert Clive introduced the dual system of administration in Bengal.

- On August 12, 1765, Clive obtained a farman from Shah Alam II, the Mughal Emperor, granting the English Company the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. In return, the Company agreed to pay the Emperor an annual subsidy of 26 lakhs of rupees.

- The Nawab of Bengal became a mere pensioner, receiving an annual sum of 53 lakhs of rupees from the Company for the support of the Nizamat.

- Clive established a Double Government in theory, with the Company as Diwan and the Nawab as Nizam.

- During the Dual System, Nawab-ud-Daulla and Saif-ud-Daull were the Nawabs of Bengal.

- The administration of Bengal was divided into Nizamat and Diwani:

1. Diwani:

(i) Concerned with revenue and civil justice.

(ii) Granted to the East India Company the right to collect revenue.

(iii) The British acquired the functions of the Diwani or revenue Diwani (Fiscal) in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa from the Mughal emperor. - 2. Nizamat:

(i) Responsible for police and criminal justice.

(ii) Entrusted to the Bengal Nawab. - Although the administration was theoretically divided between the Company and the Nawab, real power rested with the Company.

- The fiction of the Mughal emperor's sovereignty and the Nawab's formal authority was maintained.

- As Diwan, the Company collected revenues and controlled the Nizamat through the right to nominate the deputy Nizam.

- The deputy subahdar, appointed to assist the Nawab, could not be removed without the Company's consent.

- The English Resident at the Durbar made all important decisions.

- The Nawab, stripped of independent military and financial power, became a mere figurehead.

- Initially, the Company was unwilling and unable to collect revenues directly, so it appointed deputy diwans to exercise diwani functions:

- Mohammad Reza Khan for Bengal and Raja Sitah Roy for Bihar.

- Mohammad Reza Khan also served as deputy Nizam.

- The administration of Bengal was carried out through Indian agency, though real authority rested with the Company.

- This masked system reflected the Company's transition from a trading body to a ruling power.

- In England, the arrangement was noted for the immense wealth the Company expected to derive from Bengal's revenues, estimated at £4,000,000 per annum.

- The system of government associated with Clive continued under his successors Verelst (1767-69) and Cartier (1769-72).

Merits and Reasons for the Dual Government System

- The primary aim of the dual government was to improve the finances of the East India Company, which was struggling due to the costs of maintaining armies, without formally taking over Bengal.

- Clive implemented a policy of decentralization in Bengal's administration to avoid provoking Indian rulers who might have tried to expel the British.

- The dual system helped the Company avoid jealousy and rivalry from other European powers like the French, Dutch, and Portuguese, who might have withdrawn their support if Clive had fully occupied Bengal.

- Clive wisely chose not to administer Bengal directly because the Company's servants were unfamiliar with the region's languages, customs, and laws. They lacked the necessary knowledge and were too few in number to manage the administration effectively.

- Both the Board of Directors and the British Parliament opposed direct administration in Bengal. By establishing the dual government, Clive respected the Board of Directors while protecting the Company from potential backlash from the British Parliament.

- The dual government allowed the East India Company to avoid the real responsibility of governing Bengal. The Company gained power and wealth while minimizing the risks associated with administration.

- Under this system, the Nawab of Bengal was held accountable for any mistakes or failures in governance.

- Clive established the dual government out of necessity, as it provided a suitable environment for the growth of British power in India at the time. Alternative approaches could have led to disaster for the Company.

- The dual government was a temporary solution, a stop-gap arrangement to address the challenges faced by the British in 1765.

Demerits of the Dual Government

- Criticism and Disastrous Results: The Dual Government established by Clive faced criticism for its disastrous outcomes.

Power without Responsibility: The system separated power from responsibility, leading to a near-collapse of the administration in Bengal.

Abuses of Power: The lack of accountability within the company resulted in corruption and abuses of power.

- Unequal Power Distribution: The British held power and wealth, while the Nawab lacked both, shouldering only the responsibility for administration and blame for failures.

- Nawab's Struggles: The Nawab struggled to manage the administration with a limited annual grant of 50 lakhs rupees.

- Company's Benefit: The company benefited from revenues collected from Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa, while the Nawab could not perform public utility work due to insufficient funds.

- Lawlessness and Injustice: The Nawab lacked the power and funds to enforce law, resulting in widespread lawlessness, theft, and robbery.

- Judicial Influence: The Nawab's judges were influenced by British authority, leading to biased verdicts and a lack of impartiality in justice.

- Oppression of Peasantry: The dual system oppressed peasants, causing the condition of agriculture in Bengal to deteriorate.

- Revenue Collection Power: The company held exclusive power to collect revenue, preventing the Nawab from making provisions for agricultural development.

- Famine Consequences: The difficulties faced by the Nawab contributed to the great famine of 1770.

- Private Trade Impact: Private trade by company servants reduced company revenue, leading to higher revenue demands from zamindars and peasant oppression.

- Revenue Collection Decline: The decline in agriculture under the Dual Government resulted in decreased revenue collection for the Company.

- Bankruptcy Risk: The Company faced bankruptcy during the dual system period and had to seek exemption from paying £400,000 per annum demanded by Parliament.

- Private Trade Abuse: Poor administration led to the rise of private trade, with Company servants engaging in duty-free trade while local merchants faced heavy taxation.

- Local Industries Downfall: The Dual Government contributed to the decline of local industries, with company officials forcing local weavers to work exclusively for the company.

- Nawab's Servants' Oppression: The servants of the Nawab became oppressive, knowing the Nawab was under the Company's control, causing suffering to the people of Bengal.

- Partial Justice: Individuals did not receive proper justice under the Dual Government, as Nawab judges were influenced by British authority and failed to deliver impartial verdicts.

- Failure of the System: The Dual Government proved to be a failure in Bengal, leading to various administrative complications.

- End of Dual System: In 1772, Lord Warren Hastings, on the orders of the company directors, ended the unsuccessful dual system, during the tenure of Nawab Mubaraq-ud-Daulla.

The Regulating Act (1773)

- Passed by Lord North's Government to address issues in the British East India Company and its administration in India.

- Faced criticism and deemed insufficient, leading to the more comprehensive Pitt's India Act in 1784.

- Signaled the beginning of parliamentary oversight over the Company and aimed for centralized governance in India.

Background

- British Administration and Dual Government (1765-1772): The British involvement in administration during this period was marked by discreditable actions and a lack of respect.

- Bengal Famine of 1770: This famine was a tragic event in Indian history, with the Company's agents being held responsible for the government's failure, which contributed to the disaster.

- Lack of Coordination:The Company's territories in India were divided into three Presidencies: Bengal, Madras, and Bombay.

- Each was led by a Governor-in-Council accountable to the Directors in England.

- These Presidencies operated independently, making their own decisions regarding wars and treaties, leading to further complications and disgrace for the Company.

- Administrative Confusion:The Dual Government system, created by Clive in Bengal in 1765, exacerbated confusion and corruption.

- Power was divorced from responsibility, leading to plunder, oppression, and general chaos.

- Parliament could no longer be a passive observer of the Company's mismanagement.

- Wealth of Company Servants:The rich resources of Bengal allowed the Company to increase dividends significantly.

- Company servants amassed wealth through illegal trade and extortion.

- Clive, for example, returned to England wealthy at a young age, stirring resentment among other British sectors.

- Criticism of the Company grew as other British merchants and manufacturers wanted a share of the lucrative Indian trade monopolized by the Company and its officials.

- Company officials returning from India faced ridicule and were branded as exploiters, leading to increased unpopularity of the Company.

- Non-Payment of Tribute:In 1766, the Company was supposed to pay a tribute of 400,000 pounds to the British Government.

- Initially, this tribute was paid, but the Company later defaulted, claiming financial ruin due to lost tea sales to America.

- The Company was deeply in debt, with unsold tea and mismanaged finances, leading to insolvency and a plea for loans from the British Government.

The Bankruptcy of the Company

- The Dual Government in Bengal led to severe mismanagement and financial ruin for the Company.

- The Company had to borrow money from the British Government, surprising many since it appeared profitable.

- It was a poor time for bankruptcy, as the Company was unpopular.

- By seeking a loan, the Company’s Directors effectively signed their Company’s death warrant.

- A secret committee confirmed the Company’s dire financial state.

- The British Government approved a £1.4 million loan at 4% interest, with conditions like account audits.

- Simultaneously, the Government passed the Regulating Act to oversee the Company’s administration.

Transformation of the East India Company:

- The East India Company, originally a trading firm, had expanded its operations across India and maintained an army for protection.

- Due to its lack of experience in ruling the areas it had conquered, Prime Minister Lord North decided to impose government control over the Company.

Committees Established by the British Parliament:

- The British Parliament set up two committees:Secret Committee and Select Committee.

Lord North's Reforms:

- Lord North aimed to reform the East India Company’s management and establish a legal government for its Indian territories through the Regulating Act of 1773.

- This marked the beginning of government oversight in India.

- The Act created a system to supervise the East India Company without taking control.

- Despite the Company’s financial troubles, it had a strong lobby in Parliament that opposed the Act.

Reason for the Regulating Act of 1773:

- The Act was necessary due to the East India Company's challenges in governance as a trading entity, issues of corruption, the Bengal famine, and the dual governance system set by Lord Clive.

- It aimed to manage the Company’s transformation from a business to a semi-sovereign political entity, addressing judicial administration and the Company’s defeat by Hyder Ali.

Provisions of Act

The Regulating Act of 1773 and its Impact on the British East India Company

- The Act reshaped the constitution of the British East India Company in both England and India.

- While allowing the Company to keep its possessions and power in India, the Regulating Act of 1773 placed its management under British Government control.

Election of Directors:

- Directors were elected for four-year terms instead of annually.

- The number of Directors was set at 24, with one-fourth retiring each year.

- Retiring Directors could not be re-elected.

- The voting threshold in the Court of Proprietors was raised from £500 to £1,000.

Control Measures:

- The directors had to submit all correspondence about civil and military affairs in India to the Secretary of State in England.

- Correspondence related to Indian revenues had to be sent to the Treasury in England.

- The Act limited Company dividends to 6% until a loan of £1.5 million was repaid and restricted the Court of Directors to four-year terms.

Principles of Honest Administration:

- The Act prohibited anyone holding a civil or military office under the Crown from accepting any presents or rewards.

- It also forbade Company servants from engaging in private trade.

Governor General and Council:

- The Governor of Bengal was elevated to Governor General, assisted by a council of four members.

- The majority vote of the Council was binding, with the Governor General having a casting vote in case of a tie.

- Three council members constituted a quorum.

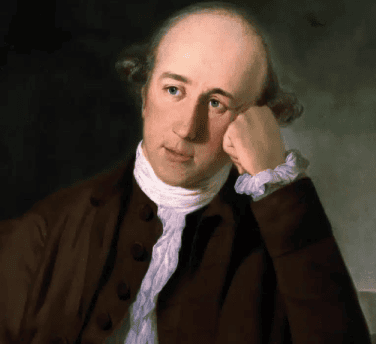

- The first Governor General was Warren Hastings, with Councillors Philip Francis, Clavering, Monson, and Barwell.

- They were to hold office for five years, removable only by the King on the Court of Directors' recommendation.

- Future appointments were to be made by the Company.

- The Governor General and Council were responsible for the civil and military government of Bengal and had authority over the Presidencies of Madras and Bombay in matters of war and peace with Indian states.

- They were empowered to govern territorial acquisitions, administer revenue, and supervise civil and military governance.

- The Governor General and Council had to keep the Court of Directors informed of their activities and obey their orders.

India’s First Supreme Court:

- The Act allowed the Crown to establish a Supreme Court in Calcutta, consisting of a Chief Justice and three judges.

- The Supreme Court was set up in 1774 with Sir Elijah Impey as Chief Justice.

- It had jurisdiction over all British subjects in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa.

- The relationship between the Supreme Court and the Government of Bengal was unclear.

- The Supreme Court had broad jurisdiction over British subjects and Company servants, with civil jurisdiction over subjects of His Majesty and persons employed by the Company.

- It had original and appellate jurisdiction and heard cases with a jury of British subjects.

- It could take cases against the Governor General and Council members, but could not arrest or imprison them.

- The Supreme Court had to respect Indian religious and social customs, with appeals going to the Governor General-in-Council.

- Subsequent amendments exempted certain actions of Company public servants from its jurisdiction.

Salaries:

- Liberal salaries were set for the Governor General (£25,000), Council members (£10,000), Chief Justice (£8,000), and puisne judges (£6,000) annually.

Criticism of the Regulating Act 1773

- The act did not effectively streamline Indian administration, and British government supervision was hindered by communication issues.

- It did not address the dire conditions of the Indian populace, particularly those suffering from famines in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa.

- Although intended to implement checks and balances, the act faltered under the pressures of Indian circumstances and its own flaws.

Governor-General at the Mercy of Council:

- The establishment of a Governor-General and a Council of four members aimed to improve governance compared to the previous system of a Governor and a large Council of 12 to 16 members.

- However, the Governor-General lacked veto power, leading to administrative challenges.

- Disunity within the council and disharmony between the council and the Governor-General hampered decision-making.

- Decisions required a majority, often resulting in deadlock, as the Governor-General was first among equals without veto power.

- In the initial years, the Governor-General (Warren Hastings) was frequently outvoted by the council, worsening the situation and creating conflict between him and his council members.

Vague Jurisdiction of the Supreme Court:

- Ambiguities in the Supreme Court's jurisdiction and its relationship with the Governor-General in Council led to conflicts between authorities.

- The Act did not clearly define the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court or its relation to the Governor-General in Council.

- The Council and the Court operated in a state of hostility due to unclear jurisdictions.

- The Governor-General in Council could not make laws without the judges' approval.

- The definition of British subjects under the Supreme Court's Charter was ambiguous, leading to confusion about who qualified as a British subject.

- The Act did not specify whether the Supreme Court would adjudicate cases based on British Laws or Native Codes.

- British Judges imposed their understanding of the law, often at odds with Indian customs and practices.

Inadequate Control of Governor-General over Presidencies:

- The Act's vague language gave provincial governors significant leeway, allowing them to act independently.

- Provincial governors in Madras and Bombay initiated wars and formed alliances without consulting the Governor-General or the Governor-in-Council.

- The Act failed to foster goodwill between the Company and the British Government.

- The Company's vulnerability increased due to perceptions of corrupt, oppressive, and economically detrimental administration.

Corruption Issues:

- Despite provisions against corruption, the Act did not effectively curb corrupt practices.

- Warren Hastings, the first Governor-General, faced major corruption charges and was impeached.

- The Council was divided into factions based on corruption allegations, with the Hastings Group and the Francis Group in conflict.

Vagueness and Compromise:

- The Act was a compromise and intentionally vague in many provisions.

- It did not clearly assert British Crown sovereignty or undermine the titular authority of the Nawab of Bengal.

- Parliament's inability to define sovereignty in India led to the Act's obscurities.

Subsequent Improvements:

- Many defects of the Act were addressed by subsequent legislation such as the Declaratory Act 1781, The Pitt’s India Act 1784, and the Amendment Act of 1786.

Continued Relevance:

- The Regulating Act of 1773 was significant as the first attempt by the British Government to regulate the Company's administration in India.

- It formally recognized parliamentary control over Indian affairs and subjected Indian territories to some level of centralized control.

- The Act laid the groundwork for a more regular, though imperfect, executive and judicial administration in India.

- It marked the beginning of a constitutional framework for India and asserted Parliament's right to legislate for the country.

Nanda Kumar Case

- This case is a clear example of corruption,nepotism, and injustice during the British era.

- Raja Nanda Kumar of Bengal was a prominent Zamindar.

- In March 1775, he presented a letter to the Council members accusing Warren Hastings of corruption.

- Nanda Kumar alleged that Warren Hastings had received a bribe from Munni Begum, the former Nawab's wife, in exchange for granting Zamindari rights.

- The case was taken up by Council member Sir Philip Francis, who encouraged Nanda Kumar to expose Hastings.

- The majority of the Supreme Council of Bengal decided that Hastings had received a bribe of Rs. 3,45,105 and ordered him to refund the money to the Company’s treasury.

- However, Warren Hastings had the power to overrule the Council’s decision.

- While the charges against Hastings were still under consideration and were eventually dropped, Nanda Kumar was arrested on charges of forgery, instigated by Warren Hastings through a Calcutta merchant named Mohan Das.

- Nanda Kumar was tried under Elijah Impey, India’s first Chief Justice, found guilty, and hanged in Kolkata on August 5, 1775, according to British parliamentary statute.

Peculiar features of the trial:

- The charge against Raja Nanda Kumar came soon after he accused Warren Hastings.

- Chief Justice Impey was a close associate of Hastings.

- Each Judge of the Supreme Court cross-examined the defense witnesses, leading to the collapse of Nanda Kumar's defense.

- After the trial, when Nanda Kumar was declared guilty, he applied for leave to appeal to the King-in-Council, but his application was rejected by the court.

- Nanda Kumar allegedly committed the offense of forgery nearly five years prior, well before the establishment of the Supreme Court.

- Neither Hindu Law nor Mohammedan Law considered forgery a capital crime.

- Warren Hastings was impeached in the House of Commons upon his return to England for crimes and misdemeanors during his time in India, particularly for the judicial killing of Nanda Kumar.

- In April 1795, the House of Lords acquitted Hastings on all charges.

- The Company subsequently compensated him with 4,000 Pounds Sterling annually.

From Diarchy to Direct Control

- In 1773, Warren Hastings became the first Governor-General of Bengal, gaining administrative authority over all of British India.

Practices of Warren Hastings

- The arrival of Warren Hastings in Bengal as Governor of the presidency of Fort William in 1772 proved to be a turning point.

- The same year, the Company was ordered by the Court of Directors to stand forth as ‘Diwan’ which meant the termination of system of ‘dual government’ and imposition of an administrative task upon the commercial men and thus the foundation of the civil service was formally laid.

- Englishmen were to be appointed as Collectors in district under the overall control of a ‘Board of Revenue’ at Calcutta, a weak system, rightly characterized by Hastings as “petty tyrants and heavy rulers of the people”.

- The foundation of the civil service in the modern sense was, nonetheless, laid down during his regime.

- Under Hastings’s term as Governor General, a great deal of administrative precedent was set which profoundly shaped later attitudes towards the government of British India.

- Hastings, having proficiency in Bengali, Urdu, Persian, understood the relationship between on acculturated civil servant and an efficient one and accordingly he emphasized on the creation of an ‘oriental elite club of the civil servants’, competent in Indian languages and responsible to Indian tradition.

- He made efforts at lifting the moral tone and intellectual standards of servants.

- ‘Dastaks’ were abolished in 1773 and those engaged in the private trade had to pay a duty of 2.5% to the Board of customs.

- Hastings separated the revenue and commercial branches.

- The Regulation Act of 1773 prohibited all officials of the Company, from the Governor-General and his councillors and Chief Justice and other judges of the Supreme Courts, from accepting gifts, donations, gratuity or rewards.

- In 1780-81, revenue and judicial administration in districts was entrusted to English officers which was the beginning of the ‘nucleus’ of the civil service with systematization and specialization of functions, essential to such service.

- By Pitt’s India Act of 1784, they were provided with definite scales of pay and emoluments.

More about Warren Hasting

- In 1758 Hastings was made the British Resident in the Bengali capital of Murshidabad, a major step forwards in his career, at the instigation of Clive.

- In 1771 he was appointed to be Governor of Calcutta, the most important Presidency.

- In Britain moves were underway to reform the divided system of government and create a single rule across all of British India with its capital in Calcutta.

- Hastings was considered the natural choice to be the first Governor General.

- While Governor, Hastings launched a major crackdown on bandits operating in Bengal which was largely successful.

- Hastings had a great respect for the ancient scripture of Hinduism and set the British position on governance as one of looking back to the earliest precedents possible.

- In 1781, Hastings founded Madrasa ‘Aliya’.

- In 1784, Hastings supported the foundation of the Bengal Asiatic Society (now the Asiatic Society of Bengal), by the oriental scholar Sir William Jones;

- Hastings’ legacy has been somewhat dualistic as an Indian administrator:

- he undoubtedly was able to institute reforms during the time he spent as governor there that would change the path that India would follow over the next several years.

- He did, however, retain the strange distinction of being both the “architect of British India and the one ruler of British India to whom the creation of such an entity was anathema.”

- He respected Indian customs but was loyal to the British mission.

- In 1784, after ten years of service, during which he helped extend and regularise the nascent Raj created by Clive, Hastings resigned.

Judicial System

Background:

- In 1765, the East India Company was granted diwani, giving it the right to collect revenue in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. However, the existing nawabi administration and the Mughal system remained intact.

- From 1765 to 1772, the judicial administration of the subah was managed by Indian officers under the Mughal system, which was applied in both civil and criminal cases.

- Clive appointed Muhammad Reza Khan to represent the Company’s civil jurisdiction. As Naib Nazim, he also handled the criminal jurisdiction on behalf of the nawab.

- The Mughal system was not centrally organized and relied heavily on local faujdars and their executive discretion.

- Sharia(Islamic law) was referenced for legitimacy, but its application varied greatly based on the case's seriousness and the interpretations of muftis and kazis.

- The focus of this judicial system was more on mutual conflict resolution rather than punitive measures, except in cases of rebellion. Punishments were often influenced by the status of the accused.

British Criticism of the System:

- Many Company officials believed that the judicial system had degenerated in the eighteenth century, attributing this decline to zamindars and revenue farmers who allegedly usurped judicial authority.

- These officials thought that these figures were more concerned with personal gain than with delivering justice, leading to complaints about the corruption(“venality”) of the justice system.

- By 1769, there were calls for European supervision to ensure a centralization of judicial authority, taking it away from zamindars and revenue farmers to reinforce the Company’s sovereignty.

How the Judicial System Evolved in India under Warren Hastings (1772 onwards)

- Warren Hastings Takes Charge (1772): Warren Hastings, as governor, aimed to take full control of the justice system in India.

- Introduction of Courts: Under Hastings, each district was to have two types of courts:

(i) Civil Court (Diwani Adalat): Handles civil cases.

(ii) Criminal Court (Faujdari Adalat): Handles criminal cases. - Retention of Mughal Nomenclature: The names of the courts reflected Mughal terminology, but the laws applied were different.

- Applicable Laws: For criminal justice, Muslim laws were used, while Muslim or Hindu laws were applied in personal matters like inheritance and marriage.

- Influence of English System: This division of law topics mirrored the English system, which left personal matters to Bishops’ courts governed by ecclesiastical law.

- Role of European District Collectors: European District Collectors presided over civil courts, aided by local experts (maulvis and Brahman pundits) to interpret indigenous laws.

- Appeal Court in Calcutta: There was an appeal court in Calcutta, led by the president and two council members.

- Criminal Courts Structure: Criminal courts were managed by a kazi (judge) and a mufti (Muslim jurist) but supervised by European collectors.

- Shift of Sadar Nizamat Adalat: The appeal court, Sadar Nizamat Adalat, was moved from Murshidabad to Calcutta.

- Initial Failures: Hastings initially struggled with the criminal justice system and had to restore Reza Khan to his position in Murshidabad.

- Changes in Civil Justice (1773-1781): Further changes occurred in the civil justice system, separating executive functions from justice administration.

- Creation of Provincial and Mofussil Courts: Instead of district courts, provincial and later mofussil courts were established, presided over by European officers.

- Establishment of the Supreme Court: The new Supreme Court acted as an appeal court for a time.

- Code of 1781: This code set rules for all civil courts and required written judicial orders.

- Issue of Conflicting Interpretations: A major problem was the differing interpretations of indigenous laws by pundits.

- Compilation of Hindu and Muslim Laws: To address this, compilations of Hindu and Muslim laws were created to standardize legal interpretations.

- Professionalization of Law: These changes made legal practice require professional expertise, leading to the emergence of trained lawyers.

- Overall Impact: The reforms of Hastings centralized judicial authority and streamlined administration.

Changes by Cornwallis:

- Civil Justice: Lord Cornwallis, through his Code of 1793, established the separation of revenue collection from civil justice administration to protect property rights from potential abuses by revenue officials.

- The new system introduced a hierarchy of courts, including zillah (district) and city courts, four provincial courts, and the Sadar Diwani Adalat, which had appellate jurisdiction.

- All courts were headed by European judges, with provisions for appointing ‘native commissioners’.

- Criminal Justice: The criminal justice system was revamped due to complaints from district magistrates regarding the issues with Islamic laws and corruption in criminal courts.

- Faujdari adalats were abolished and replaced by courts of circuit led by European judges. The Sadar Nizamat Adalat was reinstated in Calcutta under the Governor-General-in-Council’s supervision.

- This reform excluded Indians from the judicial system, reflecting a more authoritarian and racially superior approach.

Extension of Judicial System:

- The Cornwallis regulations were expanded to Banaras in 1795 and to the Ceded and Conquered Provinces in 1803 and 1805.

- However, the Bengal system struggled in Madras, where it was introduced under Lord Wellesley.

- By 1806, it was evident that in a Ryotwari area, the separation of revenue collection and judicial powers posed challenges.

- In 1814, the Court of Directors, on Thomas Munro’s advice, proposed a different system for Madras, emphasizing greater Indianisation at lower levels and uniting magisterial, revenue collection, and some judicial powers in the collector's office.

- This system was fully implemented in Madras by 1816 and later extended to Bombay by Elphinstone in 1819.

Certain unresolved issues:

- Despite advancements, unresolved issues remained in judicial administration, particularly regarding Indianisation and the codification of laws.

- These concerns were not addressed until the governorship of Lord Bentinck and the Charter Act of 1833.

Charter Act of 1833:

- The Charter Act of 1833 opened judicial positions to Indians

- and established a law commission for the codification of laws.

- Under Lord Macaulay, the law commission completed the codification by 1837, but full implementation occurred only after the 1857 revolt.

- The Code of Civil Procedure was introduced in 1859, the Indian Penal Code in 1860, and the Criminal Procedure Code in 1862.

Limitations:

- The institutionalized justice system applied only in British India.

- In the princely states, judicial administration was a mix of British Indian laws and personal decrees of the princes, who acted as the highest judicial authority.

- In British India, the judicial administration significantly differed from the Mughal rule, but the changes were often hard for ordinary Indians to comprehend.

- Judicial interpretations made laws appear complex and incomprehensible to the indigenous people. Justice became distant both physically, due to the geographical distance from district courts, and psychologically, as the indigenous people struggled with the complex judicial procedures dominated by a new class of lawyers.

- Justice also became expensive, with a backlog of court cases leading to significant delays, sometimes up to fifty years.

- The interpretation of Hindu personal laws by Brahman pundits often benefited the conservative and feudal elements in Indian society.

- The concept of equality before the law did not always apply to Europeans, and certain areas, such as the police and the army, remained unaffected by this colonial definition of the 'Rule of Law'.

|

367 videos|995 docs

|

FAQs on The Early Administrative Structure - History Optional for UPSC

| 1. What was the Dual System (Diarchy) of Government in India from 1765 to 1772? |  |

| 2. What were the key provisions of the Regulating Act of 1773? |  |

| 3. What were the criticisms of the Regulating Act of 1773? |  |

| 4. How did the Regulating Act of 1773 impact the administrative structure in India? |  |

| 5. What were the implications of the Dual System and the Regulating Act on Indian society? |  |