The Results of World War I | UPSC Mains: World History PDF Download

When the delegates of the 'victorious' powers met at Versailles near paris in 1919 to attempt to create a peace settlement, they faced a Europe that was very different to that of 1914, and one that was in a state of turmoil and chaos. The old empires of Germany, Russia and Austria-Hungary had disappeared, and various successor states were struggling to replace them. A communist revolution had take place in Russia and there appeared to be a real threat of revolution spreading across Europe. In addition, there had been terrible destruction, and the population of Europe now faced the problems of starvation, displacement and a lethal flu epidemic.

Against this difficult background, the leaders of France, Britain, the USA and Italy, attempted to create a peace settlement. The fact that their peace settlement was to break down within 20 years has led many historians to view it as a disaster that contributed to the outbreak of world War II. More recently, however, historians have argued that the peacemakers did not fully comprehend the scale of the problems in 1919, therefore it is not surprising that they failed to create a lasting peace.

The impact of the war on Europe; the situation in 1919

The human cost of the war

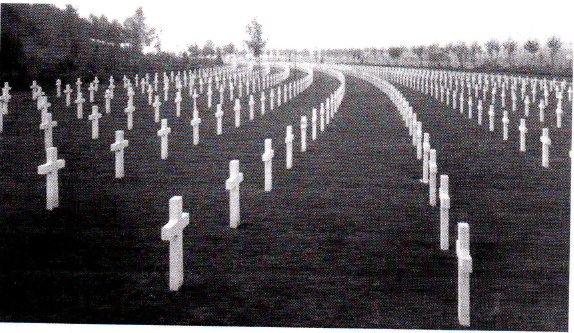

The death toll for the armed forces in World War I was appalling. Around nine million soldiers were killed, which was about 15 per cent of all combatants. In addition, millions more were permanently disabled by the war; of British war veterans, for example, 41,000 lost a limb in the fighting. In Britain, it became common to talk of a Tost generation’. Such was a particularly appropriate phrase for the situation in France, where 20 per cent of those between the ages of 20 and 40 in 1914 were killed.

Although civilians were not killed on the scale that they would be in World War II, populations had nevertheless become targets of war. In addition to the civilians killed directly in the war, millions more died from famine and disease at the end of the war and at least a further 20 million died worldwide in the Spanish flu epidemic in the winter of 1918-19.

Economic consequences

The economic impact of the war on Europe was devastating. The war cost Britain alone more than £34 billion. All powers had financed the war by borrowing money. By 1918, the USA had lent $2,000 million to Britain and France; U-boats had also sunk 40 per cent of British merchant shipping. Throughout the 1920s, Britain and France spent between one-third and one-half of their total public expenditure on debt charges and repayments. Britain never regained its pre-war international financial predominance, and lost several overseas markets.

The physical effects of the war also had an impact on the economic situation of Europe. Wherever fighting had taken place, land and industry had been destroyed. France suffered particularly badly, with farm land (2 million hectares), factories and railway lines along the Western Front totally ruined. Belgium, Poland, Italy and Serbia were also badly affected. Roads and railway lines needed to be reconstructed, hospitals and houses had to be rebuilt and arable land made productive again by the removal of unexploded shells. Consequently, there was a dramatic decline in manufacturing output. Combined with the loss of trade and foreign investments, it is clear that Europe faced an acute economic crisis in 1919.

Political consequences

The victorious governments of Britain and France did not suffer any major political changes as a result of the war. However, there were huge changes in Central Europe, where the map was completely redrawn. Before 1914, Central Europe had been dominated by multi-national, monarchical regimes. By the end of the war, these regimes had all collapsed. As Niall Ferguson writes, ‘the war led to a triumph of republicanism undreamt of even in the 1790s’ (The Pity of War, 2006).

Germany

Even before the war ended on 11 November 1918, revolution had broken out in Germany against the old regime. Sailors in northern Germany mutinied and took over the town of Kiel. This action triggered other revolts, with socialists leading uprisings of workers and soldiers in other German ports and cities. In Bavaria, an independent socialist republic was declared. On 9 November 1918, the Kaiser abdicated his throne and fled to Holland. The following day, the socialist leader Friedrich Ebert became the new leader of the Republic of Germany

Russia

As discussed in the previous chapter, Russia experienced two revolutions in 1917. The first overthrew the Tsarist regime and replaced it briefly with a Provisional Government that planned to hold free elections. This government, however, was overthrown in the second revolution of 1917, in which the communist Bolsheviks seized power and sought to establish a dictatorship. In turn this, and the peace of Brest-Litovsk that took Russia out of the war, helped to cause a civil war that lasted until the end of 1920.

The Habsburg Empire

With the defeat of Austria-Hungary, the Habsburg Empire disintegrated and the monarchy collapsed. The last Emperor, Karl I, was forced to abdicate in November 1918 and a republic was declared. Austria and Hungary split into two separate states and the various other nationalities in the empire declared themselves independent.

Turkey

The collapse of the Sultanate finally came in 1922, and it was replaced by the rule of Mustapha Kemal, who established an authoritarian regime.

The collapse of these empires left a huge area of Central and Eastern Europe in turmoil. In addition, the success of the Bolsheviks in Russia encouraged growth of socialist politics in post-war Europe. Many of the ruling classes were afraid that revolution would spread across the continent, particularly given the weak economic state of all countries.

Impact of the war outside of Europe: the situation in 1919

America

In stark comparison to the economic situation in Europe, the USA emerged from the war as the world’s leading economy. Throughout the war, American industry and trade had prospered as US food, raw materials and munitions were sent to Europe to help with the war effort. In addition, the USA had taken over European overseas markets during the war, and many American industries had become more successful than their European competitors. The USA had, for example, replaced Germany as the world’s leading producer of fertilizers, dyes and chemical products. The war also led to US advances in technology - the USA was now world leader in areas such as mechanization and the development of plastics.

Wilson hoped that America would now play a larger role in international affairs and worked hard at the peace conference to create an alternative world order in which international problems would be solved through collective security (see next chapter). However, the majority of Americans had never wanted to be involved in World War I, and once it ended they were keen to return to concerns nearer to home: the Spanish flu epidemic, the fear of communism (exacerbated by a series of industrial strikes) and racial tension, which exploded into riots in 25 cities across the USA. There was also a concern that America might be dragged into other European disputes.

Japan and China

Japan also did well economically out of the war. As in the case of America, new markets and new demands for Japanese goods brought economic growth and prosperity, with exports nearly tripling during the war years. World War I also presented Japan with opportunities for territorial expansion; under the guise of the Anglo-Japanese alliance, it was able to seize German holdings in Shandong and German-held islands in the Pacific, as well as presenting the Chinese with a list of 21 demands that aimed for political and economic domination of China. At the end of the war, Japan hoped to be able to hold on to these gains.

China, which had finally entered the war on the Allied side in 1917, was also entitled to send delegates to the Versailles Conference. Their hopes were entirely opposed to those of the Japanese: they wanted to resume political and economic control over Shandong and they wanted a release from the Japanese demands.

Problems facing the peacemakers in 1919

The Versailles peace conference was dominated by the political leaders of three of the five victorious powers: David Lloyd George (Prime Minster of the UK), Georges Clemenceau (Prime Minster of France) and Woodrow Wilson (President of the USA). Japan was only interested in what was decided about the Pacific, and played little part. Vittorio Orlando, Prime Minster of Italy, played only a minor role in discussions and in fact walked out of the conference when he failed to get the territorial gains that Italy had hoped for.

The first problem faced by the peacemakers at Versailles was the political and social instability in Europe, which necessitated that they act speedily to reach a peace settlement. One Allied observer noted that ‘there was a veritable race between peace and anarchy’.

Other political issues, however, combined to make a satisfactory treaty difficult to achieve:

- The different aims of the peacemakers

- The nature of the Armistice settlement and the mood of the German population

- The popular sentiment in the Allied countries.

The Aims of the Peacemakers

In a speech to Congress on 8 January 1918, Woodrow Wilson stated US war aims in his Fourteen Points, which can be summarized as follows:

- Abolition of secret diplomacy

- Free navigation at sea for all nations in war and peace

- Free trade between countries

- Disarmament by all countries

- Colonies to have a say in their own future

- German troops to leave Russia

- Restoration of independence for Belgium

- France to regain Alsace and Lorraine

- Frontier between Austria and Italy to be adjusted along the lines of nationality

- Self-determination for the peoples of Austria-Hungary

- Serbia to have access to the sea

- Self-determination for the people in the Turkish Empire and permanent opening of the Dardanelles

- Poland to become an independent state with access to the sea

- A League of Nations to be set up in order to preserve the peace.

- As you can see from his points above, Wilson was an idealist whose aim was to build a better and more peaceful world. Although he believed that Germany should be punished, he hoped that these points would allow for a new political and international world order. Self-determination - giving the different ethnic groups within the old empires of Europe the chance to set up their own countries - would, in Wilson’s mind, end the frustrations that had contributed to the outbreak of World War I. In addition, open diplomacy, world disarmament, economic integration and a League of Nations would stop secret alliances, and force countries to work together to prevent a tragedy such as World War I happening again.

- Wilson also believed that the USA should take the lead in this new world order. In 1916, he had proclaimed that the object of the war should be ‘to make the world safe for democracy’; unlike the ostensibly more selfish aims of the Allied powers, the USA would take the lead in promoting the ideas of democracy and self-determination.

- Wilson’s idealist views were not shared by Clemenceau and Lloyd George. Clemenceau (who commented that even God had only needed Ten Points) wanted a harsh settlement to ensure that Germany could not threaten France again. The way to achieve this would be to combine heavy economic and territorial sanctions with disarmament policies. Reparations for France were necessary not only to pay for the terrible losses inflicted upon their country, but also to keep Germany weak. Clemenceau was also keen to retain wartime links with Britain and America, and was ready to make concessions in order to achieve this aim.

- Lloyd George was in favour of a less severe settlement. He wanted Germany to lose its navy and colonies so that it could not threaten the British Empire. Yet he also wanted Germany to be able to recover quickly, so that it could start trading again with Britain and so that it could be a bulwark against the spread of communism from the new Bolshevik Russia. He was also aware that ‘injustice and arrogance displayed in the hour of triumph will never be forgotten or forgiven.’ He was under pressure from public opinion at home, however, to make Germany accountable for the death and suffering that had taken place (see below).

- The aims of Japan and Italy were to maximize their wartime gains. The Italian Prime Minster, Vittorio Orlando, wanted the Allies to keep their promises in the Treaty of London and also demanded the port of Fiume in the Adriatic. Japan, which had already seized the German islands in the Pacific, wanted recognition of these gains. Japan also wanted the inclusion of a racial equality clause in the Covenant of the League of Nations in the hope that this would protect Japanese immigrants in America.

The Armistice Settlement and the Mood of the German Population

- When the German government sued for an end to fighting, they did so in the belief that the Armistice would be based on Wilson’s Fourteen Points. It offered an alternative to having to face the ‘total’ defeat that the nature of this war had indicated would happen. In reality, the Armistice terms were very tough, and were designed not only to remove Germany’s ability to continue fighting, but also to serve as the basis for a more permanent weakening of Germany. The terms of the Armistice ordered Germany to evacuate all occupied territory including Alsace-Lorraine, and to withdraw beyond a 10km-wide neutral zone to the east of the Rhine. Allied troops would occupy the west bank of the Rhine. The Germans also lost all their submarines and much of their surface fleet and air force

- When the German Army returned home after the new government had signed the Armistice, they were still greeted as heroes. For the German population, however, the defeat came as a shock. The German Army had occupied parts of France and Belgium and had defeated Russia. The German people had been told that their army was on the verge of victory; the defeat did not seem to have been caused by any overwhelming Allied military victory, and certainly not by an invasion of Germany.

- Several days after the Armistice had been signed, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, a respected German commander, made the following comment: ‘In spite of the superiority of the enemy in men and materials, we could have brought the struggle to a favourable conclusion if there had been proper cooperation between the politicians and the army. The German Army was stabbed in the back.’

- Although the German Army was in disarray by November 1918, the idea that Germany had been ‘stabbed in the back’ soon took hold. The months before the Armistice was signed had seen Germany facing mutinies and strikes and attempts by some groups to set up a socialist government. Therefore the blame for defeat was put on ‘internal’ enemies - Jews, socialists, communists. Hitler would later refer to those who had agreed to an armistice in November 1918 as the ‘November Criminals’.

- Thus, at the start of the Versailles Conference, the German population believed that they had not been truly defeated; even their leaders still believed that Germany would play a part in the peace conference and that the final treaty, based on Wilson’s principles, would not be too harsh. There was, therefore, a huge difference between the expectations of the Germans and the expectations of the Allies, who believed that Germany would accept the terms of the treaty as the defeated nation.

The popular mood in Britain, France, Italy and the USA

- Lloyd George, Clemenceau and Orlando also faced pressure from the popular mood in their own countries, where the feeling was that revenge must be exacted from the Germans for the trauma of the last four years. Encouraged by the popular press, the populations of Britain and France in particular looked to the peacemakers at Versailles to ‘hang the Kaiser’ and ‘squeeze the German lemon until the pips squeak'. The French having borne the brunt of the fighting, would be satisfied with nothing less than a punitive peace.

- The press closely reported all the details of the Versailles Conference and helped put pressure on the delegates to create a settlement that would satisfy popular demands. Clemenceau and Lloyd George also knew that their political success depended on keeping their electorates happy, which meant obtaining a harsh settlement. Similarly, Orlando was under pressure from opinion at home to get a settlement that gave Italy the territorial and economic gains it desired and which would at last make Italy into a great power.

- In America, however, the electorate had lost interest in the Versailles settlement and Wilson’s aims for Europe. Mid-term elections held on 5 November 1918 saw Americans reject Wilson’s appeal to voters to support him in his work in Europe. There were sweeping gains for his Republican opponents, who had been very critical of his foreign policy and his Fourteen Points. When he sailed for Europe in December 1918, he left behind a Republican dominated House of Representatives and Senate and a hostile Foreign Relations Committee. He thus could not be sure that any agreements reached at Versailles would be honoured by his own government.

The Terms of the Treaty of Versailles

After six hectic weeks of negotiations, deals and compromises, the German government was presented with the terms of the peace treaty. None of the powers on the losing side had been allowed any representation during the discussions. For this reason, it became known as the diktat. The signing ceremony took place in the Hall of the Mirrors at Versailles, where the Germans had proclaimed the German Empire 50 years earlier following the Franco-Prussian War. The 440 clauses of the peace treaty covered the following areas:

War Guilt

The infamous Clause 231, or what later became known as the ‘war guilt clause’, lay at the heart of the treaty:

The Allied and Associated Governments affirm and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.

Article 231, Treaty of Versailles, 1919

This clause allowed moral justification for the other terms of the treaty that were imposed upon Germany.

Disarmament

It was generally accepted that the pre-1914 arms race in Europe had contributed to the outbreak of war. Thus the treaty addressed disarmament directly. Yet while Germany was obliged to disarm to the lowest point compatible with internal security, there was only a general reference to the idea of full international disarmament. Specifically, Germany was forbidden to have submarines, an air force, armoured cars or tanks. It was allowed to keep six battleships and an army of 100,000 men to provide internal security. (The German Navy sank its own fleet at Scapa Flow in Scotland in protest.) In addition, the west bank of the Rhine was demilitarized (i.e. stripped of German troops) and an Allied Army of Occupation was to be stationed in the area for 15 years. The French had actually wanted the Rhineland taken away from Germany altogether, but this was not acceptable to Britain and the USA. Finally, a compromise was reached. France agreed that Germany could keep the (demilitarized) Rhineland and in return America and Britain gave a guarantee that if France were ever attacked by Germany in the future, they would immediately come to its assistance.

Territorial Changes

Wilson’s Fourteen Points proposed respect for the principle of self-determination, and the collapse of large empires gave an opportunity to create states based on the different nationalities. This ambition was to prove very difficult to achieve and, unavoidably, some nationals were left in countries where they constituted minorities, such as Germans who lived in Czechoslovakia. The situation was made even more complex by the territorial demands of the different powers and of the economic arrangements related to the payment of reparations.

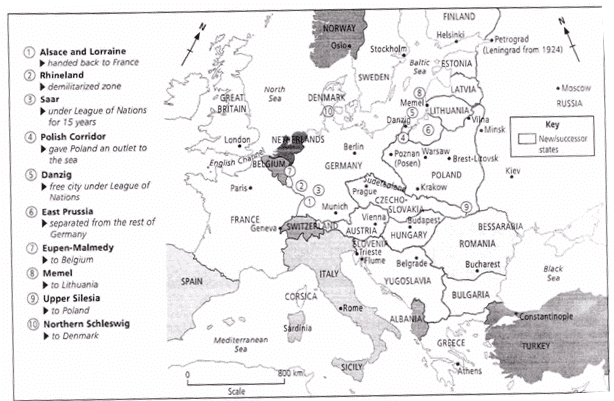

The following points were agreed upon:

- Alsace-Lorraine, which had been seized from France after the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, was returned to France.

- The Saarland was put under the administration of the League of Nations for 15 years, after which a plebiscite was to allow the inhabitants to decide whether they wanted to be annexed to Germany or France. In the meantime, the coal extracted there was to go to France.

Territorial A changes resulting from the Versailles Treaty

Territorial A changes resulting from the Versailles Treaty - Eupen, Moresnet and Malmedy were to become parts of Belgium after a plebiscite in 1920. Germany as a country was split in two. Parts of Upper Silesia, Poznan and West Prussia formed part of the new Poland, creating a ‘Polish Corridor’ between Germany and East Prussia and giving Poland access to the sea. The German port of Danzig became a free city under the mandate of the League of Nations.

- North Schleswig was given to Denmark after a plebiscite (South Schleswig remained German).

- All territory received by Germany from Russia under the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was to be returned. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were made independent states in line with the principle of self-determination.

- The port of Memel was to be given to Lithuania in 1922.

- Union (Anschluss) between Germany and Austria was forbidden.

- Germany’s African colonies were taken away because, the Allies argued, Germany had shown itself unfit to govern subject races. Those in Asia (including Shandong) were given to Japan, Australia and New Zealand and those in Africa to Britain, France, Belgium and South Africa. All were to become ‘mandates’, which meant that the new countries came under the supervision of the League of Nations.

Mandates

Germany’s colonies were handed over to the League of Nations. Yet Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations reflected a change in attitude towards colonies, requiring all nations to help underdeveloped countries whose peoples were ‘not yet able to stand up for themselves’. The mandate system thus meant that nations who were given Germany’s colonies had to ensure that they looked after the people in their care; they would also be answerable to the League of Nations for their actions. ‘A’ mandate countries - including Palestine, Iraq and Transjordan (given to Britain) and Syria and the Lebanon (given to France) - were to become independent in the near future. Colonies that were considered to be less developed and therefore not ready for immediate independence were ‘B’ mandates. These included the Cameroons, Togoland and Tanganyika, and were also given to Britain and France. Belgium also received a ‘B’ mandate - Rwanda-Urundi. ‘C’ mandate areas were considered to be very backward and were handed over to the powers that had originally conquered them in the war. Thus the North Pacific Islands went to Japan, New Guinea to Australia, South-West Africa to the Union of South Africa and Western Samoa to New Zealand.

Reparations

Germany’s ‘war guilt’ provided justification for the Allied demands for reparations. The Allies wanted to make Germany pay for the material damage done to them during the war. They also proposed to charge Germany for the future costs of pensions to war widows and war wounded. There was much argument between the delegates at the conference on the whole issue of reparations. Although France has traditionally been blamed for pushing for a high reparations sum, and thus stopping a practical reparations deal, in fact more recent accounts of the negotiations at Versailles blame Britain for making the most extreme demands and preventing a settlement. In the end it was the Inter-Allied Reparations Commission that, in 1921, came up with the reparations sum of £6,600 million.

Punishment of war Criminals

The Treaty of Versailles also called for the extradition and trial of the Kaiser and other ‘war criminals’. However, the Dutch government refused to hand over the Kaiser and the Allied leaders found it difficult to identify and find the lesser war criminals. Eventually, a few German military commanders and submarine captains were tried by a German military court at Leipzig, and received fines or short terms of imprisonment. These were light sentences, but what is important about the whole process is that the concept of ‘crimes against humanity’ was given legal sanction for the first time.

The settlement of Eastern and South-Eastern Europe

Four separate peace treaties were signed with Austria (Treaty of St Germain), Hungary (Treaty of Trianon), Bulgaria (Treaty of Neuilly) and Turkey (Treaty of Sevres, revised by the Treaty of Lausanne). Following the format of the Treaty of Versailles, all four countries were to disarm, to pay reparations and to lose territory.

The Treaty of St Germain (1919)

By the time the delegates met at Versailles, the peoples of Austria-Hungary had already broken away from the empire and were setting up their own states in accordance with the principle of self-determination. The conference had no choice but to agree to this situation and suggest minor changes. Austria was separated from Hungary and reduced to a tiny land-locked state consisting of only 25 per cent of its pre-war area and 20 per cent of its pre-war population. It became a republic of seven million people, which many nicknamed ‘the tadpole state’ due to its shape and size. Other conditions of the Treaty of St Germain were:

- Austria lost Bohemia and Moravia - wealthy industrial provinces - to the new state of Czechoslovakia

- Austria lost Dalmatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina to a new state peopled by Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, a state that became known as Yugoslavia

- Poland gained Galicia

- Italy received the South Tyrol, Trentino and Istria.

In addition, Anschluss (union with Germany) was forbidden and Austrian armed forces were reduced to 30,000 men. Austria had to pay reparations to the Allies, and by 1922 Austria was virtually bankrupt and the League of Nations took over its financial affairs.

The Treaty of Trianon (1920)

Hungary had to recognize the independence of the new states of Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia and Austria. In this treaty it lost 75 per cent of its pre-war territory and 66 per cent of its pre-war population:

- Slovakia and Ruthenia were given to Czechoslovakia

- Croatia and Slovenia were given to Yugoslavia

- Transylvania and the Banat of Temesvar were given to Romania.

In addition, the Hungarian Army was limited to 35,000 men and Hungary had to pay reparations.

Hungary complained bitterly that the newly formed Hungarian nation was much smaller than the Kingdom of Hungary that had been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and that more than three million Magyars had been put under foreign rule.

The Treaty of Neuilly (1919)

- In the Treaty of Neuilly, Bulgaria lost territory to Greece and Yugoslavia. Significantly, it lost its Aegean coastline and therefore access to the Mediterranean. However, it was the only defeated nation to receive territory, from Turkey.

- Compared to the treaties that Germany had imposed on Russia and Romania earlier in 1918, the Treaty of Versailles was quite moderate. Germany’s war aims were far-reaching and, as shown in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, indicate that Germany would have sought huge areas of land from the Allies if it had won. Thus, the Allies can be seen to have exercised considerable restraint. The treaty deprived Germany of about 13.5 per cent of its territory (much of this consisted of Alsace-Lorraine, which was returned to France), about 13 per cent of its economic productivity and just over 10 per cent of its population. In addition, it can be argued that France deserved to be compensated for the destruction of so much of its land and industry. German land had not been invaded and its farmland and industries therefore remained intact.

- The treaty in fact left Germany in a relatively strong position in the centre of Europe. Germany remained a dominant power in a weakened Europe. Not only was it physically undamaged, it had gained strategic advantages. Russia remained weak and isolated at this time, and Central Europe was fragmented. The peacemakers had created several new states in accordance with the principle of self-determination (see below), and this was to create a power vacuum that would favour the expansion of Germany in the future. Anthony Lentin has pointed out the problem here of creating a treaty that failed to weaken Germany, but at the same time left it ‘scourged, humiliated and resentful’.

- The huge reparations bill was not responsible for the economic crisis that Germany faced in the early 1920s. In fact, the issue of banknotes by the German government was a major factor in causing hyper-inflation. In addition, many economic historians have argued that Germany could have paid the 7.2 per cent of its national income that the Reparations Schedule required in the years 1925-29, if it had reformed its financial system or raised its taxation to British levels. However, it chose not to pay the reparations as a way of protesting against the peace settlement.

- Thus it can be argued that the treaty was reasonable, and not in itself responsible, for the chaos of post-war Germany. Why then is the view that the treaty was vindictive and unjust so prevalent, and why is it so often cited as a key factor in the cause of World War II? The first issue is that while the treaty was not in itself exceptionally unfair, the Germans thought it was and they directed all their efforts into persuading others of their case. German propaganda on this issue was very successful, and Britain and France were forced into several revisions of the treaty, while Germany evaded paying reparations or carrying out the disarmament clauses.

- The second issue is that the USA and Britain lacked the will to enforce the terms of the treaty. The coalition that put the treaty together at Versailles soon collapsed. The USA refused to ratify the treaty, and Britain, content with colonial gains and with strategic and maritime security from Germany, now wished to distance itself from many of the treaty’s territorial provisions. Liberal opinion in the USA and Britain was influenced not only by German propaganda, but also by Keynes’s arguments for allowing Germany to recover economically.

- France was the only country that still feared for its security and which wanted to enforce Versailles in full. This fact explains why France invaded the Ruhr in 1923 in order to secure reparation payments. It received no support for such actions, however, from the USA and Great Britain, who accused France of ‘bullying’ Germany. As the American historian, William R. Keylor, writes, ‘it must in fairness be recorded that the Treaty of Versailles proved to be a failure less because of the inherent defects it contained than because it was never put into full effect’ (The Twentieth Century World and Beyond, 2006).

- The one feature of the Versailles settlement that guaranteed peace and the security of France was the occupation of the Rhineland. Yet the treaty stipulated that the troops should.

The Treaty of Lausanne (1923)

The provisions of the Treaty of Lausanne ran as follows:

- Turkey regained Eastern Thrace, Smyrna, some territory along the Syrian border and several Aegean islands

- Turkish sovereignty over the Straits was recognized, but the area remained demilitarized

- Foreign troops were withdrawn from Turkish territory

- Turkey no longer had to pay reparations or have its army reduced.

What were the criticisms of the peace settlements in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe?

It was very difficult to apply the principle of self-determination consistently and fairly. Because Czechoslovakia needed a mountainous, defensible border and because the new state lacked certain minerals and industry, it was given the ex-Austrian Sudetenland, which contained around three and a half million German speakers. The new Czechoslovakia set up on racial lines therefore contained five main racial groups: Czechs, Poles, Magyars, Ruthenians and German speakers. Racial problems were also rife in the new Yugoslavia, where there were at least a dozen nationalities within its borders. Thus the historian Alan Sharp writes that ‘the 1919 minorities were probably more discontented than those of 1914’ (Modern History Review, November 1991).

As well as ethnic strife, the new states were weak politically and economically. Both Hungary and Austria suffered economic collapse by 1922. The weakness of these new states was later to create a power vacuum in this part of Europe and thus the area became an easy target for German domination.

The treaties caused much bitterness:

- Hungary resented the loss of its territories, particularly Transylvania. Czechoslovakia, Romania and Yugoslavia later formed the Little Entente, with the aim of protecting one another from any Hungarian attempt to regain control over their territories.

- Turkey was extremely bitter about the settlement, and this bitterness led to a takeover by Kemal and the revision of the Treaty of Sevres.

- Italy was also discontented. It referred to the settlement as 'die mutilated peace’ because it had not received the Dalmatian coast, Fiume and certain colonies. In 1919, Gabriele D’Annunzio, a leader in Italy’s fascist movement, occupied Fiume with a force of supporters in the name of Italian nationalists, and in 1924 the Yugoslavians gave Fiume to the Italians.

What was the impact of the war and the peace treaties by the early 1920s?

Political Issues

- Although Western Europe was still familiar on the map in 1920, this was not the case in Eastern Europe, where no fewer than nine new or revived states came into existence: Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary and Yugoslavia. Meanwhile, Russia’s government was now a Bolshevik dictatorship that was encouraging revolution abroad. The frontiers of new states thus became the frontiers of the Europe from which Russia was excluded. Russia was not invited to the Versailles Conference and was not a member of the League of Nations until 1934.

- The new Europe remained divided not only between the ‘victors’ and the ‘defeated’, but also between those who wanted to maintain the peace settlement and those who wanted to see it revised. Not only Germany, but also Hungary and Italy, were active in pursuing their aims of getting the treaties changed. Despite Wilson’s hopes to the contrary, international ‘blocs’ developed, such as that formed by the Little Entente. The peacemakers had hoped for and encouraged democracy in the new states. Yet the people in Central Europe had only experience with autocracy, and governments were undermined by the rivalry between the different ethnic groups and by the economic problems that they faced.

- Although Britain and France still had their empires and continued their same colonial policies, the war saw the start of the decline of these powers on the world stage. The role of America in the war had made it clear that Britain and France were going to find it hard to act on their own to deal with international disputes; the focus of power in the world had shifted away from Europe. Furthermore, the war encouraged movements for independence in French and British colonies in Asia and Africa. As RM.H. Bell writes, ‘Empires were wider than before, but in many places they were less secure’ (Twentieth Century Europe, 2006).

Economic Issues

- As we have seen, the war caused severe economic disruption in Europe. Germany suffered particularly badly, but all countries of Europe faced rising prices; ‘the impact of inflation on generations which had grown accustomed to stable prices and a reliable currency was enormous, and was as much psychological as economic. The lost landmark of a stable currency proved much harder to restore than the ruins of towns and villages’ (RM.H. Bell, Twentieth Century Europe, 2006). The middle classes of Europe were hit especially hard by inflation, which destroyed the wealth of many bourgeois families. In Germany, for example, the total collapse of the currency meant that the savings of middle-class families were made completely worthless.

- In Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, the new fragmentation of the area hindered economic recovery. There was now serious disruption in what had been a free trade area of some 50 million inhabitants. From 1919, each country tried to build up its economy, which meant fierce competition and high tariffs. Attempts at economic cooperation foundered and any success was wrecked by the Great Depression. As noted, only America and Japan benefited economically from the war, and they went on to experience economic prosperity until the Wall Street Crash in 1929.

Social Changes

- The war also swept away the traditional structures in society. Across Europe, the landed aristocracy, which had been so prominent before 1914, lost much of its power and influence. In Russia, the revolution rid the country of its aristocracy completely. In the lands of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, estates were broken up; many governments, such as that of Yugoslavia, undertook land reform and distributed land out to the peasants. In Prussia, the land owners (Junker) kept their lands but lost much of their influence with the decline of the military and the collapse of the monarchy.

- Other groups of people benefited from the war. Trade unions were considerably strengthened by the role that they played in negotiating with the governments during the war to improve pay and conditions for the valuable war workers. In both Britain and

- France, standards of health and welfare also rose during the war, thus improving the lives of the poorest citizens. Measures were introduced to improve the health of children. In Britain, social legislation continued after the war with the Housing Act of 1918, which subsidized the building of houses, and the Unemployment Insurance Acts of 1920 and 1921, which increased benefits for unemployed workers and their families.

- After the war, women gained rights in society to which they had previously been denied. Such changes were reflected in a growing female confidence and changes in fashion and behaviour. In Britain and America the so-called ‘flappers’ wore plain, short dresses, had short hair, smoked cigarettes and drank cocktails. This kind of behaviour would have been considered unacceptable before the war. In Britain, some professions also opened up to women after the war; they could now train to become architects and lawyers and were allowed to serve on a jury.

- The end of the war also saw women getting the vote in a number of countries; Russia in 1917, Austria and Britain in 1918, Czechoslovakia, Germany, the Netherlands, Poland and Sweden in 1919 and America and Belgium in 1920. The role that women played in the war effort was a contributory factor to this shift in some countries, though it was not the only factor.

- In Britain, for instance, the pre-war work of the suffrage movements in raising awareness of women’s rights issues was also important. Yet the new employment opportunities that women had experienced during the war did not continue after the war, with most women giving up their work and returning to their more traditional roles in the home.

|

50 videos|67 docs|30 tests

|

FAQs on The Results of World War I - UPSC Mains: World History

| 1. What was the impact of World War I on Europe and what was the situation in 1919? |  |

| 2. What were the problems faced by the peacemakers in 1919? |  |

| 3. How did the Armistice Settlement and the mood of the German population contribute to the post-war scenario? |  |

| 4. What was the popular mood in Britain, France, Italy, and the USA after World War I? |  |

| 5. What were the terms of the Treaty of Versailles and how did it impact the post-war era? |  |

|

Explore Courses for UPSC exam

|

|